Further Reading

Relevant Family History

Maiden, Effie Meek. Ed. Anne Meek and Marilyn Brooks Hammonds. Home in the Wilderness. Norfolk, VA: Anne Meek, 2003.

Roney, Lisa. Freeman Cemetery website. Developed from a family booklet written and created by Anne Meek and Marilyn Brooks Hammonds. 2018. https://www.freemancemetery.org/

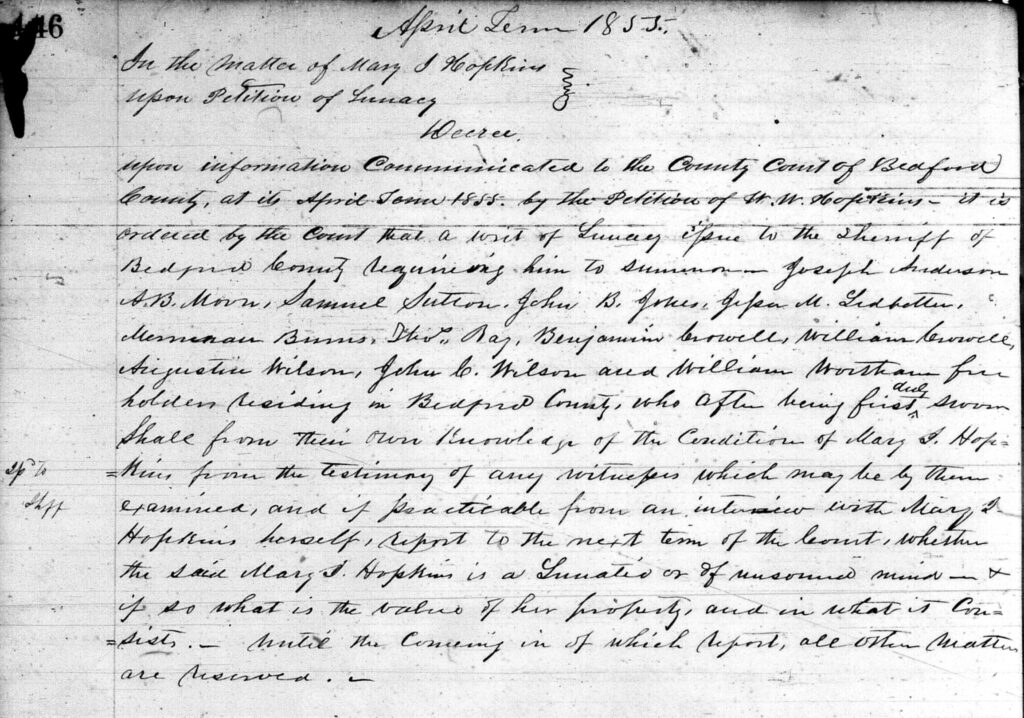

Nineteenth-Century Women’s Mental Health and Property Rights

I first became aware of the use of mental health diagnoses as a way to disempower nineteenth-century women by reading the classic story “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (first published in 1892 in The New England Journal) and in the literary criticism of Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar in The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Imagination (New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1979).

More direct accounts and historical focus can be found in:

Bailey, Chad. “Surnames and Women’s Rights in the 19th Century in Tennessee, Part II—The 19th Century Women.” Jonesboro Genealogical Society. 23 Aug 2018. https://jgstn.org/8-may-1991-surnames-and-womens-rights-in-the-19th-century-in-tennessee-part-ii-the-19th-century-women/

Baird, Bob. “Women’s Rights: Women, Wives, and Widows.” Bob’s Genealogy Filing Cabinet: Southern and Colonial Genealogies. n.d. https://genfiles.com/articles/womens-rights/

Bly, Nellie. Ten Days in a Mad House. 1887. Many current editions available.

Chesler, Phyllis. Women and Madness. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin Press, 2005. Orig. 1972.

Geller, Jeffrey L., and Maxine Harris. Women of the Asylum: Voices from Behind the Walls 1840-1945. New York: Doubleday, 1994.

Mitchell, Christi A. “Neither Hers Nor Theirs: Dower and Household Relationships

Between Widows, Family, and Friends in York County, Maine.” Maine History 38.3 (1 Jan 1999), 166-185. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol38/iss3/2/

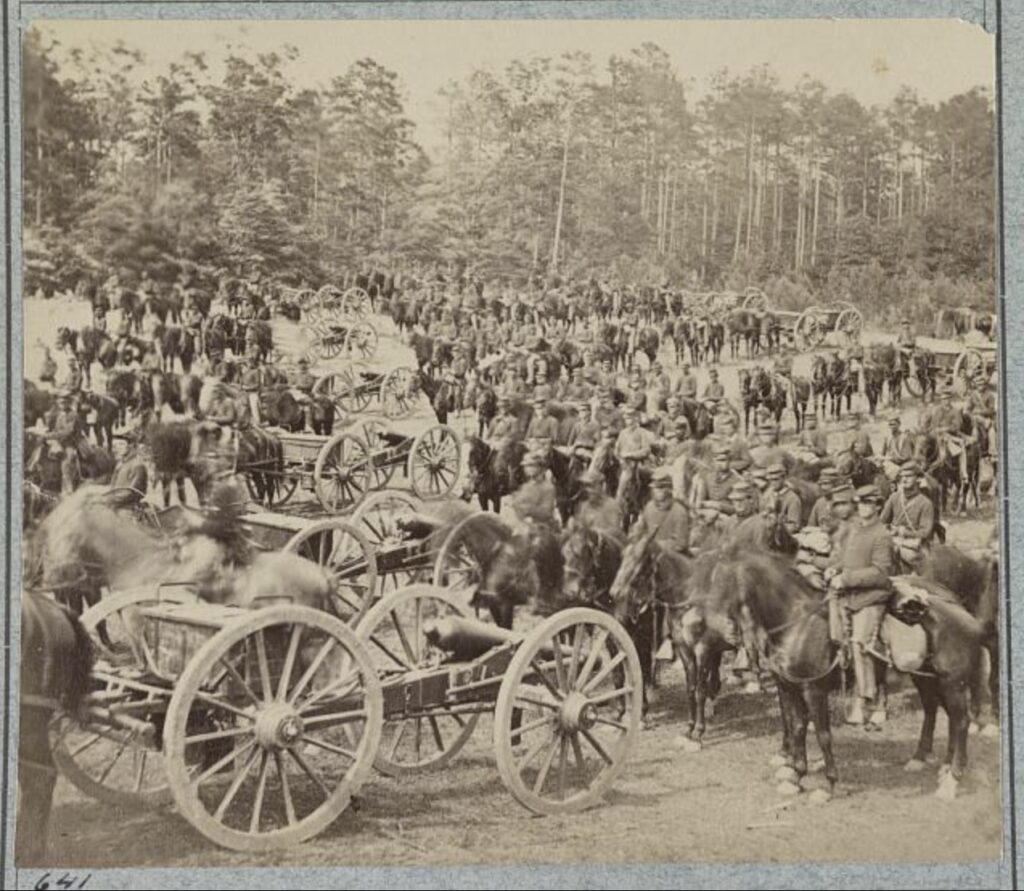

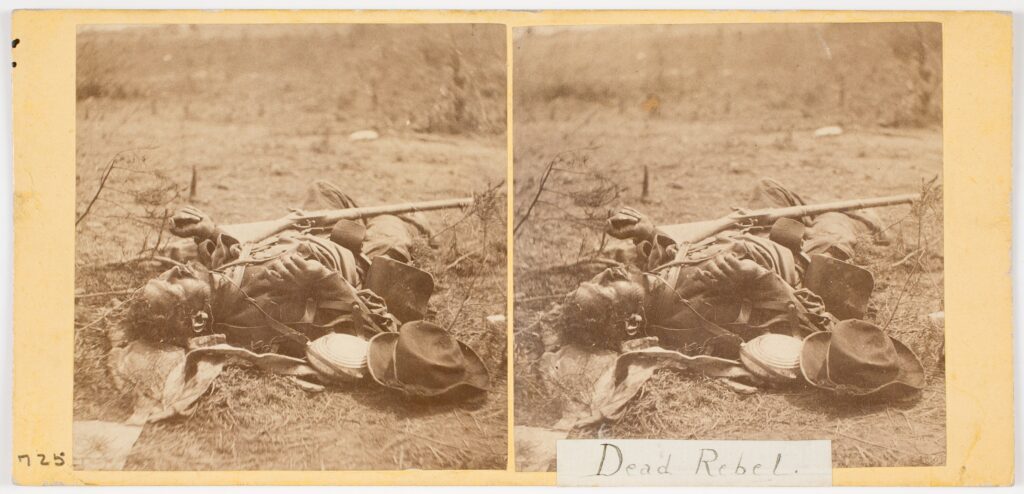

The Civil War in West Tennessee and Northern Mississippi

One visceral demonstration of the constant conflicts across the area of West Tennessee and Northern Mississippi is a video on YouTube, The American Civil War: Every Day (v. 2). 26 Oct 2018, posted under the pseduonym Emperor TigerStar. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pDEK4gJBKW0

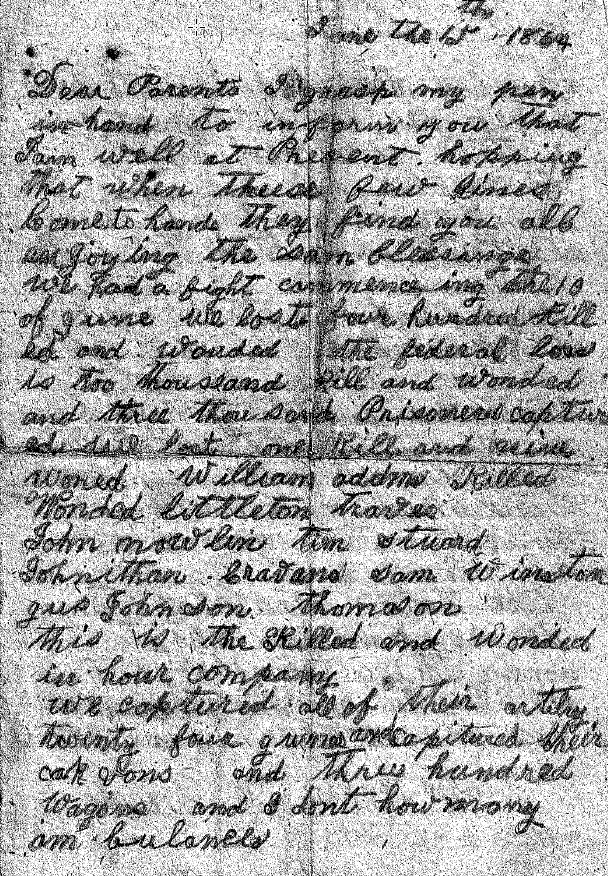

Examples of the ways in which Tennesseans, their families, and their farms were torn apart during the war, as well as the often mixed feelings they had about “the cause,” can be found in many of the letters in the archive of the Family Papers of Charles B. Moore (1822-1901), another distant family member of mine and a Union supporter, who lived in Texas and Illinois during the war but still had family in Middle and West Tennessee. Charles B. Moore Family Papers, 1832-1917, part of The Civil War and Its Aftermath: Diverse Perspectives, UNT Digital Library, University of North Texas Libraries Special Collections. https://digital.library.unt.edu/explore/collections/CWADP/

More scholarly works focused on the conflicts that included and affected my ancestors include:

Bearss, Edwin Cole. Forrest at Brice’s Crossroads. Dayton, OH: Morningside Books, 2012.

Bennett, Stewart L., and Doug Bostick The Battle of Brice’s Crossroads. Civil War Sesquicentennial series. Charleston, SC: The History Press of Arcadia Publishing, 2020.

Daniel, Larry J. Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee: A Portrait of Life in a Confederate Army. Civil War America series. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 2003.

Hubbard, John Milton. Ed. Booker Roper. Notes of a Private: Annotated. Orig. Memphis, Tennessee: E. H. Clark, 1909. Reprint 2018 by Booker Roper.

Hurst, Jack. Nathan Bedford Forrest: A Biography. New York: Vintage, 1994.

Lord, Walter. The Past That Would Not Die. New York: Harper & Row, 1965.

Levine, Bruce. The Fall of the House of Dixie: The Civil War and the Social Revolution That Transformed the South. New York: Random House, 2013.

Mitcham, Samuel W., Jr. Bust Hell Wide Open: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest. Regenery History, 2016.

“Myths, Legends, and the Search for Truth. Website of the Battle of Franklin [TN] Trust. https://boft.org/myths

Rhea, Godon. “Why Non-Slaveholding Southerners Fought.” Address to the Charleston Library Society, 25 January 2011. American Battlefield Trust website. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/why-non-slaveholding-southerners-fought [Please note that some of the language in this article is objectionable.]

Watkins, Sam. Ed. and intro., M. Thomas Inge. Company Aytch or A Side Show of the Big Show. New York: Plume, 1999.

Wills, Brian Steel. A Battle from the Start: The Life of Nathan Bedford Forrest. New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

Woodward, Colin Edward. Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army during the Civil War. A Nation Divided series. Charlottesville: UVAP, 2014.

Attempts at Confrontation and Healing

Auslander, Mark. The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race & Finding an American Family. Athens, GA: UGAP, 2011.

Branan, Karen. The Family Tree: A Lynching in Georgia, a Legacy of Secrets, and My Search for the Truth. New York: Atria, 2016.

DeWolf, Thomas Norman, and Sharon Morgan. Gather at the Table: The Healing Journey of a Daughter of Slavery and a Son of the Slave Trade. Boston: Beacon Press, 2012.

Miles, Tiya. All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack. New York: Random House, 2021.

Mozingo, Joe. The Fiddler on Pantico Run: An African Warrier, His White Descendants, A Search for Family. New York: Free Press, 2012.

Perry, Imani. South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon Line to Understand the Soul of a Nation. New York: Ecco, 2022.

Russell, Lauren. Descent. Saxtons River, VT: Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2020.

Seidule, Ty. Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause. New York: St. Martin’s, 2021.

Smith, Clint. How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America. New York: Little, Brown, 2021.

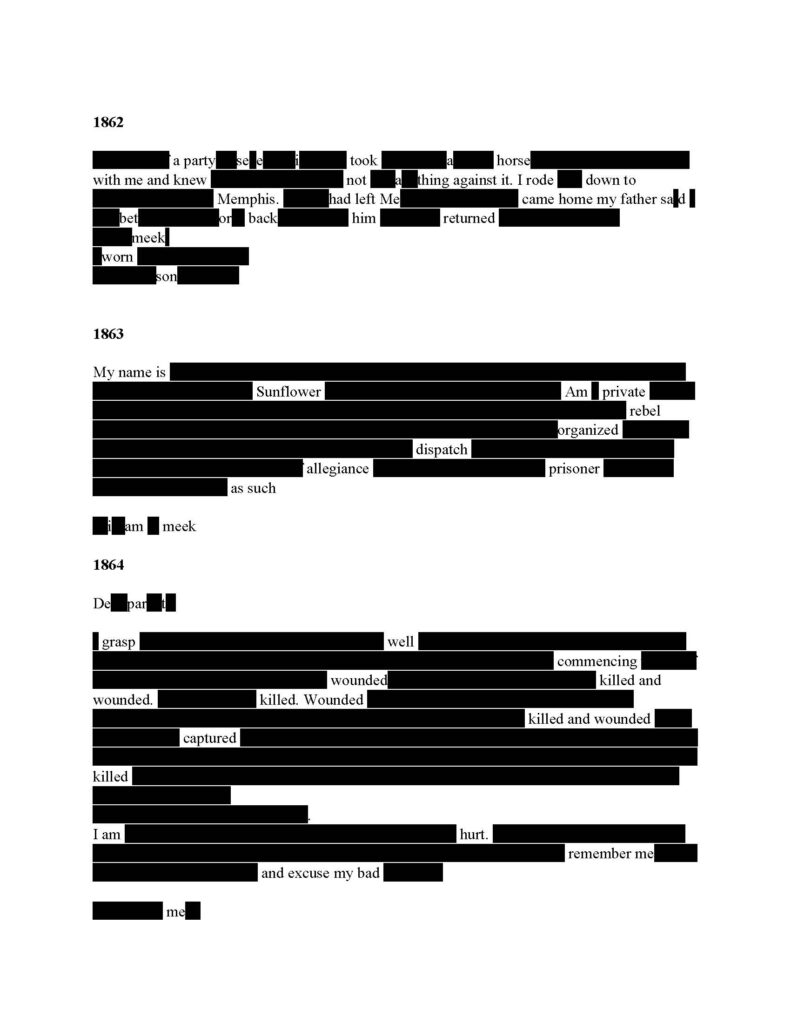

Erasure or Black-Out Poetry

Best, B. J., and C. Kubasta. “A Process of Illumination: Conversations about Erasure Poetry.” Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets website, n.d. https://www.wfop.org/a-process-of-illumination-conversations-about-erasure-poetry

Lewis, Kara. “Hidden Meanings: The Power & Precision of Erasure Poetry.” 6 November 2019. Read Poetry website. https://www.readpoetry.com/hidden-meanings-the-power-precision-of-erasure-poetry/

This article originally appeared in July 2025.

Lisa Roney is the author of Sweet Invisible Body, The Best Possible Bad Luck: Poems, and Serious Daring, as well as short work in numerous journals. She spent 20 years as a professor of creative writing and five as editor of The Florida Review. She lives in Florida with her husband and three cats.