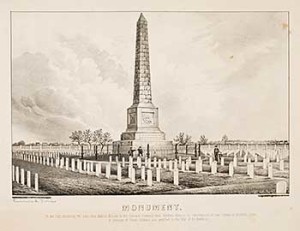

Southern communities that erected soldier monuments also incorporated both mourning and commemoration into their memorial programs, but for Southerners, the mourning aspect was even more pronounced than it was for their Northern counterparts. In the North, communities mourned a great loss of life as families lamented the faraway or unknown graves of loved ones, but victory in the war served as a balm for grief. In Southern towns, where much greater percentages of the white male population had participated in the war, grief over individual loss was coupled with the need to cope with the defeat of the Southern cause. Further, while Union soldiers who had died in battle were given dignified burials in national cemeteries, Confederate remains were denied entrance into these spaces. Instead, Southern women formed Ladies’ Memorial Associations, organizations that established Confederate cemeteries and paid for the reburial of Southern soldiers’ bodies and the erection of monuments to their memory. Stonewall Confederate Cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, with its even rows of simple headstones and tall columnar monument, is such a site (fig. 7). Founded in 1866 as a section of the larger Mount Hebron Cemetery, this resting place for the bodies of 2,575 Confederate soldiers received its soldier monument in 1879.

The long delay  8. Confederate Monument, Winchester, Virginia, 1879, attributed to Thomas Delahunty. Photograph courtesy of the author.between the founding of Stonewall Confederate Cemetery and the dedication of its monument speaks to the scarcity of funds for monument building in the war-ravaged South. In the first years after the war, most Southern communities prioritized the rebuilding of towns and the reburial of Confederate soldiers over the purchase of memorial sculpture. But as a famous poem by Henry Timrod implies, a monument was usually part of the plan. Timrod’s “Ode Sung on the Occasion of Decorating the Graves of the Confederate Dead” was written for a ceremony that took place on June 16, 1866, at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. In the first few stanzas, Timrod explains that a monument will soon watch over the deceased in their sleep:

8. Confederate Monument, Winchester, Virginia, 1879, attributed to Thomas Delahunty. Photograph courtesy of the author.between the founding of Stonewall Confederate Cemetery and the dedication of its monument speaks to the scarcity of funds for monument building in the war-ravaged South. In the first years after the war, most Southern communities prioritized the rebuilding of towns and the reburial of Confederate soldiers over the purchase of memorial sculpture. But as a famous poem by Henry Timrod implies, a monument was usually part of the plan. Timrod’s “Ode Sung on the Occasion of Decorating the Graves of the Confederate Dead” was written for a ceremony that took place on June 16, 1866, at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. In the first few stanzas, Timrod explains that a monument will soon watch over the deceased in their sleep:

Sleep sweetly in your humble graves,

Sleep, martyrs of a fallen cause;

Though yet no marble column craves

The pilgrim here to pause.

In seeds of laurel in the earth

The blossom of your fame is blown,

And somewhere, waiting for its birth,

The shaft is in the stone!

Timrod makes clear that while the soldiers’ cause is lost, their fame carries on, and he reassures the sleeping soldiers that their marble monument is already planned, lying in wait in a stone block. Soon, just as the finished shaft will be born from the uncut stone, its memorial function will grow in the visitor’s mind from the presence of the monument.

Like Martin Milmore’s Union soldier in Forest Hills Cemetery, the Confederate soldier in Stonewall Confederate Cemetery stands at quiet rest, gazing off to one side as if remembering fallen comrades (fig. 8). But this soldier takes the mourning motif even further by standing with reversed arms, his rifle barrel pointed at the ground. The command to “reverse arms,” first appearing in infantry drill manuals around the time of the Civil War, was employed at solemn occasions, such as soldiers’ funerals or military executions, to symbolize mourning, respect, and even surrender. A connection between soldier monuments and “reverse arms” is evoked in the first verse of the song “Brave Battery Boys,” composed for the dedication of a monument to the Bridges Battery at Rose Hill Cemetery in Chicago on May 30, 1870:

We come with reversed arms, O comrades who sleep,

To rear the proud marble, to muse and to weep,

To speak of the dark days that yet had their joys

When we were together—

Brave Battery Boys.

In the poem, joy and sorrow are merged in front of the marble monument, which is honored by the ceremonial rifle gesture. In a Confederate context, this gesture points to the still-complicated position of Southern memory toward the end of the Reconstruction era. This monument mourns the dead Confederate soldiers and the Lost Cause for which the war was fought.

The soldier monuments of the post-Civil War era were not always so explicitly connected with the funerary sphere. As the decades passed, the raw collective grief generated by the war’s terrible losses mellowed into a general appreciation of the soldiers’ sacrifice in battle. In other words, the monuments became less associated with individual mourning families, and instead answered a larger cultural need for civic pride and education. By the 1880s, monuments North and South were generally erected in prominent civic locations rather than in cemeteries. Soldier statues, too, lost their mourning focus, and the contemplative air of the statues in Forest Hills Cemetery and Stonewall Confederate Cemetery was exchanged for a more militant, confident attitude. Monumental inscriptions focused less on reflections of loss and more on the war’s nationalistic and ideological aims. But the soldier monument continued its material association with the cemetery industry, as the same monument firms were often responsible for producing both soldier monuments and funerary sculpture. This army of bronze and granite sentinels, dotted across the landscape, continues to evoke the enormous impact of the Civil War on the lives of American citizens.

Acknowledgements

The author pursued this research with the assistance of the American Antiquarian Society, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Winterthur Museum, and the University of Delaware. Special thanks to Wendy Bellion for her unflagging support of this project and to editors Sarah Anne Carter and Ellery Foutch for their insightful comments.

Further Reading

Civil War soldier monuments have been the subject of several scholarly works, including Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, N.J., 1997); Thomas J. Brown, The Public Art of Civil War Commemoration: A Brief History with Documents (Boston, 2004); Carol Grissom, Zinc Sculpture in America, 1850-1950 (Newark, Del., 2009); and Cynthia Mills and Pamela H. Simpson, eds., Monuments to the Lost Cause: Women, Art, and the Landscapes of Southern Memory (Knoxville, Tenn., 2003).

For more on how the Civil War affected America’s culture of death and mourning, see Drew Gilpin Faust, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, 2008); and Mark S. Schantz, Awaiting the Heavenly Country: The Civil War and America’s Culture of Death (Ithaca, N.Y., 2008).

To learn more about the reburial of Civil War soldiers in the North and the South, see John R. Neff, Honoring the Civil War Dead: Commemoration and the Problem of Reconciliation(Lawrence, Kansas, 2005); William A. Blair, Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South, 1865-1914 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2004); and Caroline E. Janney, Burying the Dead but Not the Past: Ladies’ Memorial Associations and the Lost Cause (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2008).

The Chipstone Foundation is a Milwaukee-based arts organization devoted to the study and interpretation of early American decorative arts and material culture.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.2 (Winter, 2014).

Sarah Beetham is a doctoral candidate in art history at the University of Delaware. Her dissertation, titled “Sculpting the Citizen Soldier: Reproduction and National Memory, 1865-1917,” investigates citizen soldier monuments in an effort to understand the relation between sculptural form, national memory, and the marketing of multiplied art in the late nineteenth century.