One way to tell a drunkard’s story is by the distances he travels. John Gough was born in Sandgate, England, in 1817, and was indentured to a family going to America and sent across the Atlantic. For two years he worked for the family on a farm in Oneida County in Western New York. When it became apparent they would not keep their promise to educate him for a trade, he got permission from his father to strike out on his own. He returned to New York City, alone and “glad to have my fate in my own hands, as it were.” Gough found work as a bookbinder’s apprentice, only to lose the job in the economic downturn. He soon made the wrong kind of friends, and by the age of 17 was already a heavy drinker. He traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, found work and lost it by his drinking. By 1842, Gough had ended up in Worcester, Massachusetts. He had gained and lost more jobs; had married, had a child, and drunk his family into destitution. He stood by, intoxicated, as his son died, and again when his wife died in childbirth with their second child. Gough’s wandering had slowed to standstill when, just 25 years old, he stumbled out of a bar into an unusually cold October night and, not for the first time, contemplated suicide.

From that moment until his death in 1886, Gough would transform these facts of his early life into an extraordinary career as a temperance lecturer. As a drunkard, Gough had been “utterly alone in the world,” he later wrote, “forgotten by God, as well as abandoned by man.” Yet by 1844, he was the headliner of a national temperance convention in Boston (fig. 1). Over the next four decades, Gough traveled by carriage, railroad, and steamship to tell his story to audiences in churches, theaters, town halls, and auditoriums in every part of the United States. By the end of his life, Gough’s speaking engagements added up to over 11,000 lectures and some 500,000 miles of travel across North America, as well as two tours of England, and other appearances in Europe. In the course of these travels, Gough became known as “the apostle of temperance,” a role model and emblem for the largest and longest lasting grass-roots social and political movement in U.S. history, and arguably the most popular lecturer of his lifetime.

The story that Gough told about the suffering caused by his alcoholism and his eventual recovery would become a staple of American culture, both high and low. A distinctively modern genre of confession, it anticipates the late 20th century interest in pathographies, a genre of biographical writing focused on personal disaster and dysfunction, ranging from James Frey’s fictionalized memoir A Million Little Pieces to “reality television” dramas such as Intervention. By situating Gough’s story of hard times within the context of the early 1840s, we can learn new things about the historical origins and cultural functions of this kind of narrative in American life. How did a working-class drunkard with little formal education become a narrator of hard times to society at large? How did Gough’s story circulate, and what might his celebrity tell us about the evolving meaning of class in nineteenth-century America? What role did he play in helping Americans think about the powers of the will in the midst of impersonal social and economic circumstances of modernity? To follow Gough’s story among the philanthropic, commercial, and ideological interests that brought it into the public sphere and kept it there, is to discover a surprisingly modern politics of culture: contests over the collective meaning of personal suffering, and competing ways of packaging moral authority in the marketplace of culture.

The story Gough told did not begin its public life in American culture as a written text. It was, rather, an oral genre that drunkards improvised about their personal suffering and recovery among the Washingtonians, a grass-roots movement that began in 1840, when six artisans in a Baltimore tavern pledged to stop drinking. Within months, as news of their reform spread, hundreds of local chapters were formed, enlisting thousands of members primarily in the northeastern and Midwestern states. This movement introduced a new story about drunkards to the public sphere of social reform. The story was new because of its plot, which ended with the redemption of a class of persons which, in older narratives of temperance activists, had been consigned to death, or written off in the statistical profiles of crime, madness, and poverty. The story was also new, however, in the way it was told, which Abraham Lincoln described in an address to the Springfield Washingtonians in 1842: “When one who has long been known as a victim, stands up with tears of joy trembling in his eyes, to tell of the miseries once endured, now to be endured no more forever, of his once naked and starving children now clothed and fed comfortably; of a wife long weighed down with woe, weeping, and a broken heart, now restored to health, happiness and renewed affection … how simple his language; there is a logic, and an eloquence in it, that few, with human feelings, can resist.” As Lincoln’s description begins to suggest, the story’s appeal derived from its sincerity and authenticity. What made the drunkard’s story “irresistible” was its joining of a Christian allegory of redemption to a sensational melodrama of domestic suffering. In telling their stories, drunkards exemplified a secular salvation that was freely given to all who might choose the humble grace of sobriety by signing the total abstinence pledge. Given the depths of the worldly hell from which they had suddenly risen in 1840, the Washingtonians were all the more miraculous for their “eloquence,” the simple language and logic by which they described the realities of poverty and deprivation.

Gough only lived to tell his tale of wretchedness and woe because a stranger tapped him on the shoulder, and invited him to a meeting of the Washingtonian Temperance Society in Worcester. To this group, Gough first spoke in public about his poverty and abjection, and by their simple creed and example—to talk only from personal experience, and to help other drunkards—Gough learned how to shape this experience as a story. As it was ritualized in the fellowship and outreach of the Washingtonians, the “experience story” offered Gough and countless other drunkards a script for ethical practice. Before neighbors, acquaintances, and strangers who had cast them in morality plays about vice and failure, drunkards asserted their autonomy—their capacity to choose a path besides the one to which they had been consigned by circumstances of birth, by the fatalities of habit, the accumulation of poor options, and bad decisions. Offering hope to others trapped in the despair from which they had risen, the public telling of their stories allowed drunkards to reclaim their very humanity, what they invariably called their “nobility” and “independence” as men. Unable to rely on the education and privilege that previously identified temperance reform with middle-class gentility and professional expertise, these reformed drinkers could nevertheless offer each other friendship, planting “their standard of moral government” on “the noble and manly feelings of human sympathy and love.”

Gough’s story began to leave a paper trail when, just two months after his reformation, he was enlisted by the Worcester Washingtonians to go on a speaking tour of the surrounding region. In the first of several scrapbooks in which Gough documented his speaking career, his first clipping was from The Worcester Waterfall, a paper edited by his fellow Washingtonian Jesse Goodrich. Dated December 31, 1842, it announced, “this talented and worthy young mechanic is about to commence the business of lecturing.” For the next six months, the paper supplied its readers with steady coverage of Gough’s appearances, as they began in nearby towns of Upton, Sutton, and Norfolk, and branched out to New Hampshire and Maine. Correspondents in these towns reported on the sizes of his audiences and on his success in getting pledges even from among “hard drinkers” or “hard cases,” praised his effectiveness as a speaker, and promoted him to other communities. A January 28 “Letter from Sutton” declared Gough to be “the man above all others, for the work in which he was engaged.” Goodrich not only publicized the intensive schedule of Gough’s engagements, but also handled bookings on his behalf at least until the fall of 1843. In return, Gough served as a subscription agent for Goodrich, selling to the local readers along his path a newspaper that was busy selling him. Throughout Gough’s first years on the lecture circuit, Goodrich continually ratified his institutional identity as “the Washingtonian lecturer” and the devoted emissary of “Washingtonian principles.” Meanwhile, the network of Washingtonian papers with which Goodrich exchanged news continued to certify Gough as “the Washingtonian lecturer,” his words as touching “the Washingtonian chord.”

From the outset, then, this “business of lecturing” in which Gough and Goodrich collaborated was devoted to selling Washingtonianism as a brand in the marketplace for reform. With the rapid spread of the movement, the publicity surrounding the missionary outreach of the original Baltimore group in New York and lectures by reformed drunkards had already become a familiar, if not notorious, feature of the cultural landscape. During a visit to Dedham, Massachusetts, in the spring of 1843, for example, Gough received coverage from the Norfolk American, a political paper which, as the Norfolk Washingtonian reported, “had never uttered a syllable in favor of a Washingtonian lecturer”: “we think him the best lecturer we have heard of that class of men called ‘reformed drunkards.’ He is a foreigner by birth, an Englishman we should suppose, from his correct pronunciation. His own experience as an intemperate man, tho’ dreadful, is not more terrible than that of many others of that unfortunate class of men, but in truthful descriptions of scenes of misery produced by drunkenness we have never heard him surpassed.” As the notice suggests, a tale of suffering, however impressive on its own, loses its novelty upon repetition. Before Gough set foot into a hall or church with his own experience, then, the Washingtonians had turned the drunkard’s misery into a predictable genre of lecture delivered by “that class of men called ‘reformed drunkards.'” If the content of Gough’s story seemed old hat, however, the quality and style of his “truthful descriptions” had never been seen or heard before.

Gough’s life as a public speaker was launched by the Washingtonians, but it flourished because he found ever-larger audiences within the temperance movement and eventually beyond it. Gough found these audiences by acquiring two new, influential patrons: Moses Grant, a prominent philanthropist and civic leader in Boston who throughout the 1830s and 1840s sought to publicize the link between drinking and poverty; and Rev. John Marsh, who served as “corresponding secretary” of the American Temperance Union. Like Goodrich, Grant and Marsh organized Gough’s appearances and took an active hand in marketing him in the press. Both men had years of experience in the organization and promotion of temperance from within the mainstream of protestant philanthropy and the reform press in the Northeast. Through their many contacts with philanthropists, ministers, and temperance societies, they opened doors for Gough that had literally been closed to the Washingtonians. In August of 1843, for example, Grant brought Gough to Boston for his first official lecture in the city, essentially giving him the mainstream movement’s stamp of approval. Grant advertised Gough’s special suitability for observant Christians, and promoted an appearance at the Odeon theater by noting in the Boston Recorder that his “Sabbath Evening addresses have been so very acceptable in our city.” Due in large part to Grant’s influence, Boston’s Mercantile Journal began to follow Gough’s appearances both in and out of Boston, including in their detailed coverage frequent references to scripture readings, prayer, and the ministers in his company.

As if poaching him from the minor leagues, Grant and Marsh broadened Gough’s appeal, and helped him transform a mission of reform into a vocation. Marsh read about Gough’s speaking in Worcester in a newspaper, and by the fall of 1843 had hired him as an agent for the American Temperance Union, the preeminent mainstream temperance organization which since the 1830s had developed a bureaucratic, centralized infrastructure linking together local associations, publishing and circulating reports, and sponsoring regional meetings and conferences. “I felt that such an instrument of rousing the public mind should not be lost,” Marsh later wrote, “and I made arrangements with him to go through the State of New York, and to speak with me in all the principal towns and cities.” Marsh took Gough on a speaking tour where he spoke in churches of all denominations, to the Auburn State prison, and even to colleges, which “released the students from their evening studies, that they might hear the young orator, who admirably adapted himself to such an audience.” Giving hundreds of lectures before larger, more respectable audiences, a “reformed inebriate” was transformed into an “orator” despite his working-class background.

As Gough’s story traveled out of the lecture hall and onto the printed page in 1843, his reputation as a speaker spread to what we would now call the mainstream press. Take, for example, the first clipping in Gough’s scrapbook featuring his name in a headline: “GREAT MASS TEMPERANCE MEETING AT FANEUIL HALL—MR. GOUGH,THE DISTINGUISHED WASHINGTONIAN.” Appearing in the Daily Mail, one of Boston’s major dailies, the paper introduced Gough to a general audience, offering some biographical background. It could not assume, in contrast to temperance papers, that its readers were adherents to the “cause” or “reform.” Rather, the article sought to explain why “he appears to be the chief attraction of the day”:

Mr. Gough is really a genius, sui generis, and a perfect genius for the Washingtonians. His broad mouthed denunciations of rum selling, his eloquent and pathetic descriptions of personal suffering, his endless budget of stories, anecdotes, songs, “gaieties and gravitas,” is enough to move a heart of stone, or make an inebriate explode with laughter.

Within the genre of Washingtonian address, the Mail set Gough apart as a “genius, sui generis” for his resources and tactics as a performer. Along with the expected attack on rum-sellers and accounts of personal suffering, Gough brought emotional depth and range, employing an “endless budget” of stories and songs that allowed him, despite a cold, to give “most abundant satisfaction” to “one of the most crowded audiences that ever congregated within the walls of old Faneuil.” Like so many other reviews that Gough received in his first two years as a lecturer, this article gives special emphasis to the diversity of his appeal, which retained the Washingtonian’s common touch of the barroom humor appreciated by inebriates, while engaging a whole new constituency who had seemed beyond the reach of reform: “In some instances, hundreds of the most gay and fashionable young men have walked up and signed the pledge, after hearing his discourses; young men that no other influence on earth could move to such a step.” Suggesting that the special “influence” Gough exerted on even “the most gay and fashionable” was of a piece with his skills as a performer, the article closed by telling readers to attend his next lecture that evening: “Mr. Gough will ‘both speak and sing’ to the great edification and amusement … of all who may choose to attend. Go and hear him, by all means. It is as good as a play, and twice as useful.”

So what, then, made this reformed drunkard’s story so compelling to diverse people—”as good as a play, and twice as useful”? Gough had learned to tell a story from his father, a veteran of the Napoleonic wars who, though unable to temper his “stern discipline” and “military habits,” earned his boy’s affection by reenacting battles he had witnessed “until my young heart would leap with excitement,” as Gough later wrote. Gough learned to read and write when he spent a couple of years at a local seminary. He discovered his speaking voice while reading aloud to his mother as she did piecework as a seamstress, when strangers stopped by their cottage “attracted by my proficiency in this art.” It was in the bars of New York, however, where Gough would hone his talents as a performer: “I possessed a tolerably good voice, and sang pretty well, having also the faculty of imitation rather strongly developed, and being well stocked with amusing stories, I got introduced into the society of thoughtless and dissipated young men, to whom my talents made me welcome.” When he found himself without work, his teenage “longing for society” led him to drinking; when his drinking made him unable to keep work, he sought jobs on the stage, eventually leaving New York for stints with theater troupes in Providence and Boston. As alcoholism took hold of Gough’s life, he put his performance skills to work nursing his addiction: “After every other resource had failed me,” Gough wrote, “my custom was to repair to the lowest grogshops, and there I might be usefully found, night after night, telling facetious stories, singing comic songs, or turning books upside down and reading them whilst they were moving round, to the great delight and wonder of a set of loafers who supplied me with drink in return.”

From the dislocation, isolation, and despair to be found at the margins of economic and social life, Gough furnished the stock episodes of the drunkard’s picaresque that he would go on to deliver, night after night and year after year, from the lecture platform. Working without notes, Gough used mimicry and variety to dramatize his own experiences. Reporters invariably commented on the “graphic” nature of his “illustrations,” his rapid shifting among “scenes,” his “personations” of villains and victims along the drunkard’s path. I”n the evolving media environment of the 1840s, it was Gough’s inventions as a performer that enabled him to render “truthful descriptions” of already well-known miseries, giving “to motive and appetite and principles life-like and breathing existences that all can recognize.” In the comfort of the lecture hall, Gough’s “vivid transitions from argument to pathos” made the social world of intemperance emotionally accessible and physically present, from the “mincing steps” of stumbling inebriate to the genteel hypocrisies of “the social glass.” Making experience a vehicle for social witness, Gough gave anonymous facts the narrative power of allegory. As the New York Tribune declared in 1844: “You can almost hear the sigh—the cry—the curse—the low jest—almost see the thin wife, the bloated husband—the days of light and the days of darkness—the scenes of happiness, and the midnight hours of despair—as they are to be seen in many a street of our city, as they are found in the downward track of almost every drunkard.”

In both the grog shop and the lecture hall, Gough used the same skills as a storyteller—dining out, so to speak, on his uncommon ability to enlist sympathy from diverse audiences. In putting his personal suffering on display to win the the affection of thousands of people who would gather to see him across the United States, however, Gough converted the insecurity and emotional need that marked his experience of poverty and degradation into habits of a new sort of moral personality—a mission to convey, as widely as one man could, the reality of the drunkard’s suffering, in its most quotidian and sensational details. That mission required freeing social activism from the cultural spaces and proprieties to which it had been confined. As the Providence Journal noted, Gough was “able to display his surpassing power of imitation, anecdote, and humorous remarks to much better advantage in a hall principally devoted to secular uses than he can do with propriety in a church or place devoted entirely to religious worship.” Gough became especially famous for his “thrilling” and “terrifying” impersonation of the delirium tremens. Indeed, in 1843 he made his first public appearance in Boston in the lower hall of the Boston Museum, just months before the 1844 debut of its first theater production, The Drunkard, which featured the tremens as a sensational climax but was sold to respectable audiences of women and children as a “moral lecture.” He was sometimes referred to as an “evangelical comedian”: people “who dare not patronize a theater, and therefore do not know what acting is, go and laugh safely with Gough, the great platform actor.” As the truth of Gough’s story came to be measured by the range and accuracy of its telling, Gough’s career as a lecturer perhaps helped to popularize a taste for theatricality. Indeed, the story of moral agency he repeatedly testified to on the platform would, in print, be objectified as acting—the ability to bring personal experiences to truthful life for the entertainment of an expanding middle class.

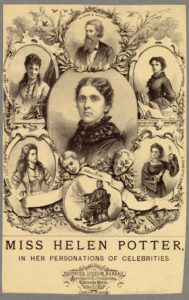

Gough acquired remarkable celebrity as a performer by carrying his story among an array of spaces, networks, and media that were rapidly reshaping education and leisure in antebellum America. By 1844, he had traveled 12,000 miles, and gotten 29,000 signatures from people who, after listening to Gough tell the true story of his own experience, had promised to abstain from alcohol. He kept meticulous notes about these travels, piling up the stats of a major-league slugger for the temperance movement. In 1847, for example, he spoke 240 times, traveled 7,313 miles, visited 102 towns and cities, and obtained 10,936 names. In the years ahead, as newspapers amplified his reputation to regional and national audiences, Gough ceased to be the “instrument” of any particular faction of temperance reform, and built an independent career as a temperance lecturer. From the meticulous memoranda books that Gough kept on his lectures from the 1840s to the 1870s, it becomes clear that public lectures were generating a consistent revenue stream, and could support the most effective performers with an often-sizable income. In that sense, the circulation of Gough’s story coincided with the commercialization of the public lecture. By 1853, for example, Gough had gotten over his discomfort with charging admission, and was making $25 to $50 a lecture. In 1857, he earned a total of $10,000. His annual income grew in subsequent decades, so that by in the 1870s, he was making as much $26,000 a year. As these numbers demonstrate, a working-class man turned his experience of suffering in nineteenth-century America into an asset that was both commercial and moral, by cultivating a professional identity and national celebrity as a public speaker (fig. 2).

Over the course of his career, Gough carved out a social mission for his public speaking that blurred political activism, education, evangelism, and entertainment. As he did so, organizations and entrepreneurs staked competing claims to the meaning of his story, seeking to define its value as it moved among diverse spaces and institutions in the marketplace for culture. To whom did this drunkard’s story belong, and what obligations did Gough assume in its telling? Could the moral lessons of the drunkard’s suffering be separated from the realities of social inequality in which it was clothed? In John Gough’s relationship to the Washingtonians, these questions came to have very public consequences, as one drunkard’s suffering came to be fought over by new and old factions within the temperance movement—the object of ideological conflicts over the meaning of class in American life. They would have consequences as well for how John Gough came to identify with his own experience as a drunkard.

Although short-lived as a formal movement, the Washingtonian revival posed a dramatic challenge not only to the tactics of the reform establishment, but to its cultural authority as well. Equipped with personal experience alone, drunkards testified to seemingly universal and transcendent truths unmediated by the sectarian and political prescriptions by which temperance had been addressed by professional elites throughout the 1830s. As The New England Washingtonian observed in 1843, the laborers of their movement “are the hard working people … The meeting-house and the state house have other matters to attend to. They have sects to build up, and laws to make. The true reformer is not at home in such places. He can’t take off his coat in them. He can’t speak in them.” In taking off their coats and moving outside political and religious institutions, these “true reformers” were attacking the utility of the literary training, educational privilege, and middle-class gentility which ministers, doctors, and lawyers had brought to temperance reform. Defending the forum it offered to the voices and plot lines of indigent and degraded people, the paper added that it never pretended to furnish “an establishment for a marble center table, or that it would contain a feast of literature on which the Scholar might feed to satiety.” For those professional reformers who had feasted on innumerable lectures, sermons, convention proceedings, and pamphlets throughout the 1830s, the absence of literary and scholarly attributes in the experience story attested to lack of moral credibility. The occasional charlatan who passed the hat as a Washingtonian speaker, the many reformed men who relapsed, the barroom vulgarity and humor with which they seasoned their moral lessons: all of this merely confirmed a prejudice held by many that no man who had become a drunkard could be trusted with his own self-control, let alone as a paid agent of social reform. To hitch the water wagon to any recovering alcoholic was to gamble the credibility of the temperance movement on personal character which experience had already proved to be unreliable.

Allying himself with the temperance establishment, and Marsh in particular, Gough made himself a target of radical Washingtonians seeking to protect their movement from “sectarian” agendas of politics and religion. In offhand comments made during an address he gave in August of 1844, at Tremont Temple in Boston, Gough reported that he had been informed “by the leading Washingtonians that Washingtonianism, as an ism, was dead. The reason assigned for this was, that the people in these places had become disgusted with the many follies dragged before the public in connection with Washingtonianism,” including not only “theatrical exhibitions, & c.,” but “infidelity.” Gough had just returned from a lecture tour of western New York, which Marsh had organized with the explicit purpose of engaging ministers and philanthropists who had been alienated from Washingtonianism. As Gough later recalled in his third and last autobiography, Sunlight and Shadow (1881), he found that long-time temperance leaders—”faithful men… who had endured persecution for the truth’s sake”—were being “thrown into the background,” dismissed as “old fogies, slow, men who did not understand the first principles of reform.” Meanwhile, “men became leading reformers who were not qualified by experience, or training, or education, to lead,” and “reformed drunkards sneered at those who had never been intemperate, as if former degradation was the only qualification for leadership.” One can imagine how, in the early 1840s, such polemics seemed to turn the world on its head: having never been drunk, the good ministers were unfit to lead temperance reform.

In making these comments, Gough was defending the many educated, ordained “friends” who had brought the former drunkard to their homes, escorted him to towns and villages, counseled him in his struggle for faith, and tutored the former artisan in how to conduct himself on the public stage. But Gough’s words merely confirmed the suspicion of some of his brothers that he had become the puppet of his ministers. “For these utterances I was subjected to an attack which, being the first, wounded me sorely,” in which he was “called to account for mixing orthodoxy” with his temperance appeals. A Washingtonian paper attacked Gough in October of 1844, noting that he “is a reformed man, and has ample evidence in his own glorious experience of the all-conquering power of the true Washingtonian principles, and motives innumerable to lay before the poor inebriate in urging his reformation, without going into the future world for them—motives connected with this life, with the poor sufferer’s own temporal well-being and happiness.” Gough could have drawn on the “ample evidence of his own glorious experience,” but rejected common sense in favor of metaphysical questions of salvation in order to address the “future world” of the reformed. Such criticism assumed that temperance was a “holy cause” whose “all-conquering power” was proved by personal experience. Substituting theology for the presence of truth in the drunkard’s own experience, Gough was diverting attention from “motives connected with this life,” from what ordinary men could know and verify by reference to their own “temporal well-being and happiness.” Other papers piled invective onto these arguments in subsequent weeks: “A religious bigot and ignoramus.” “Perverting the cause to sectarian ends.” “Dwelling on a set of motives which he knows never had any politics in promoting this glorious reform.” To these critics, Gough had squandered the example of his own life for the sake of entirely speculative theological claims about eternal life. In short, Gough had drunk the Kool-Aid of religious ideology, and was now peddling theoretical “motives” for reform, polluting the revelations of the drunkard’s suffering with sectarian politics.

The break from “Washingtonianism” that ensued from Gough’s comments would be painful and personal, haunting him for the rest of his life. Despite the fact that Washingtonians had saved his life, he could barely bring himself to mention their name in the first two autobiographies he published, in 1845 and 1861. In his last autobiography, however, Gough would seek to vindicate himself by turning to his scrapbook, where clippings about his career had, with the passage of time, assumed the aura of historical evidence. “I have before me two volumes of scraps collected from the temperance papers of 1844-46. This was about the time when some of the societies would have no members but those who had been drunkards; who would permit no minister of the Gospel to take any part in their exercises; who occupied the whole of the Sabbath day in meeting, relating experiences, and singing songs that were occasionally objectionable.” Decades later, Gough would, in writing, swear on his personal experience to vindicate himself: “I was a Washingtonian rescued by the spirit of Washingtonians,” he wrote, “and testify of what I know in saying that more than one minister of the Gospel shut the door of his church against these men, because he could not sit still and hear in his own pulpit, before his own people and the children of his charge, such loose and sometimes vulgar utterances as were occasionally heard.” In testifying “of what I know,” Gough insists that Washingtonianism was a ministry of “spirit” rather than the body. It was a kinship he acquired by being rescued through love and compassion, after all, rather than by sharing the physical and verbal traits of a social class. But “these men” claimed the experience of degradation itself as a badge of social honor: not to bear personal witness to impersonal spirit, but to claim exclusive ownership of a profane body, identified by loose and vulgar language, by the rudeness of its songs and impiety of its conduct.

Balancing the debts his suffering had incurred among the Washingtonians with the credit it had brought him on the lecture circuit, Gough could only reenter the drunkard’s body second hand, as a character to be played on the lecture platform. It might be for comic or tragic effect, but Gough’s achievement, in the course of telling his story no less than living it, depended on turning away from the drunkard’s experience of privation. It was a life he could only share with shame, as the mortified body from which the Washingtonians had reclaimed a soul, a circumstance from which an individual had asserted his freedom. To now wear this hairshirt of degradation with working-class pride was to give up the spiritual authority of humility. To be deserving of sympathy, after all, required showing others—especially the nondrinkers in the house—a desire for social respect: self-conscious recognition of the propriety and dignity of one’s person, repudiating not only drinking but the cultural environment in which it had occurred. Gough would carry the drunkard’s suffering as personal and professional baggage, and would act it out on the stage, to sensational and lucrative effect, as a vehicle to alter the conduct and mores of others. But the degradation and despair that had owned him for seven endless years were nothing he cared to own now, as the collective identity and autonomous culture of the working class.

This drunkard’s story is worth telling, in part, for what it tells us about historical meanings of class, and how forms of communication enter into the scripting of social difference. For Washingtonians, the “moral government” of community depended on toleration and respect for social differences produced by inequality. As Gough presented himself in public, night after night, it came to require something else: that individuals free themselves from the stigma of class difference by embracing seemingly universal norms of civility, and become “respectable.” It would be tempting to find in Gough’s professional success some betrayal of his working-class origins, an abandonment of the democratic creed of the Washingtonians. And yet, in the very frequency and intensity of his movements on the lecture circuit, Gough seems to have maintained solitude in the midst of his fame. Though he befriended many prominent reformers throughout his life, he turned down invitations to dinner parties of local worthies in towns and cities he visited, as though unable to abandon his difference as a drunkard: “The more I mingle with the wise, the pure, the true, the higher my aspirations, the more intense is my disgust and abhorrence of the damning degradation of those seven years of my life.” Carrying a working-class ethos of Washingtonianism into an expanding marketplace for leisure and entertainment, perhaps this itinerant storyteller also brought—if only for an hour or two—news of our capacity for identification, despite the facts and fatalities of social difference (fig. 3).

We still have much to learn about how we live with stories: about the way that otherwise impersonal plots, voices, images, phrases, and stereotypes that make up our common repertoire of culture become intimate attributes of personal identity, mutual attachment, and social difference. To follow Gough’s movements through diverse spaces and institutional identities—from churches to theaters and auditoriums, from missionary agent to civic actor—is to perhaps learn new things about how stories are valued: not for their intrinsic art as what people in the academy now define as texts or literature, but for their social missions, as tools of personal and collective welfare, for the remaking of individuals and communities. In reading over the thousands of notices that Gough pasted into his scrapbooks, we can never hear the sound of his voice, or see his body. Like the nineteenth-century readers who encountered his story in the newspapers, we are left with the aftermath of Gough’s presence, in the paper wake of experiences that, we are repeatedly told, cannot be described. In the ephemeral and corporal presence of humanity which he embodied for so many people in the nineteenth century, Gough’s paper trail perhaps testifies to what John Dewey described in an 1888 essay as the democratic faith in the individual as a moral personality: “an ideal of spiritual life, a unity of will” for the whole community, in a world that continues to be reshaped by the divisive forces of secular liberalism and capitalist modernity.

Further reading

On the media context of social reform, see Augst, “Temperance, Mass Culture, and the Romance of Experience,” American Literary History 19:2 (2007) 297-323. On popular traditions of autobiography in the context of early American print culture, see Ann Fabian, The Unvarnished Truth: Personal Narratives in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley, 2000). For interpretations of antebellum temperance narratives, see Karen Sanchez-Eppler, Dependent States: The Child’s Part in Nineteenth-Century American Culture (Chicago, 2005); Glenn Hendler, “Bloated Bodies and Sober Sentiments: Masculinity in 1840s Temperance Narratives,” Sentimental Men: The Politics of Affect in American Culture (Berkeley, 1999), Mary Chapman and Glenn Hendler, eds.; John W. Crowley, Drunkard’s Progress: Narratives of Addiction, Despair, and Recovery (Baltimore, 1990); John W. Crowley, “Slaves to the Bottle: Gough’s Autobiography and Douglass’s Narrative,” Serpent in the Cup: Temperance in American Literature (Amherst, 1997), David S. Reynolds and Debra J. Rosenthal, eds.

Class dimensions of Washingtonian revival and temperance reform more generally are discussed in Ian Tyrell, Sobering Up: From Temperance to Prohibition in Antebellum America, 1800-1860 (Westport, 1979); Jed Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder: Temperance Reform in Cincinnati from the Washingtonian Revival to the WCTU (Urbana, 1984); Joseph Gusfield, Symbolic Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance Movement (Urbana, 1963). Temperance reform has been interpreted more recently from the perspective of gender in Elaine Frantz Parsons, Manhood Lost: Fallen Drunkards and Redeeming Women in the Nineteenth-Century United States (Baltimore, 2003); Bruce Dorsey, Reforming Men and Women: Gender in the Antebellum City (Ithaca, 2002); Holly Fletcher, Gender and the American Temperance Movement of the Nineteenth Century (New York, 2008).

This article originally appeared in issue 10.3 (April, 2010).

Thomas Augst is associate professor of English at New York University. He is the author of The Clerk’s Tale: Young Men and Moral Life in Nineteenth-Century America (2003) and the coeditor, with Kenneth Carpenter, of Institutions of Reading: The Social Life of Libraries in the United States (2007).