Antiquarian Collecting and the Transits of Indigenous Material Culture: Rethinking “Indian Relics” and Tribal Histories

Note from the column co-editors: Traditionally, Object Lessons columns have featured research projects centered on individual objects—from seventeenth-century bowling balls to glass ballot boxes—that reveal compelling stories about the past. In this issue, we have expanded that focus to include not only the study of specific objects, but also the cultures of collecting that transform the meanings of the material things under consideration.

Note from the author: This piece discusses colonial histories of collecting and handling Indigenous items, including some sensitive materials, in order to assess the nature and extent of these practices as well as Indigenous responses.

Today when researchers visit the gold-domed American Antiquarian Society (AAS) at the corner of Salisbury Street and Park Avenue in Worcester, Massachusetts, they typically focus on paper sources: printed books and ephemera, manuscripts, maps, graphics. Perhaps they are told in semi-reverent tones about the handful of objects that the Society displays in its Council Room, like a glass vial containing leaves of tea ostensibly thrown overboard at the Boston Tea Party, or the wooden highchair that accommodated young Cotton Mather. As objects linked to prominent Euro-American pasts, these items have operated as tangible tokens of identity, heritage, and public memory pertinent to specific slices of Americana. Yet few are aware that the Society once housed an enormous variety of material objects—or that Native Americans created many of them, and experienced an array of disruptions when they were removed from traditional contexts. From stone tools to buffalo robes, to wampum and ceremonial pipes, to fishing hooks and personal adornments, Indigenous objects featured prominently in earlier formations of the Society. As institutions like the AAS confront their own difficult legacies in the twenty-first century, these Indigenous objects, now largely dispersed across the Northeast and the globe, invite new reckonings.

In the nineteenth century it was no secret that the Worcester antiquarians actively solicited donations of Indigenous artifacts. They viewed “aboriginal” histories and associated “Indian relics” as vital components of the organization’s mission, shedding light on American (so-called) prehistory and the formative encounters between the continent’s original inhabitants and waves of European migrants and colonizers. The initial iterations of the AAS did not draw hard lines between types of historical sources. Its leaders and members believed all manner of traces from the past stood to contribute to national, regional, and local histories, a comprehensive mentality expressed by many other institutions of the era. Only over time did such places narrow their attentions and begin de-accessioning (giving away or discarding) material culture holdings. As a result of these decisions it has become difficult to trace the pathways of many objects. They can appear “lost,” irretrievably removed from scholarly and community sightlines as well as research endeavors.

But in actuality there are ways to begin reconnecting the pieces, using methodologies that link textual, material, visual, ethnographic, and environmental sources. The stakes of such reconnecting projects are not simply to illuminate changing histories of collecting, significant though they are. They offer an opportunity to reassess the protracted—and continuing—transits of Native objects through time and space, and to consider restorative processes by which heritage items may be brought back into conversation with Indigenous descendant communities who have so long been alienated from them.

From many material culture and museum studies perspectives, the act of “collecting” has been treated as a generative endeavor. Museums and related exhibitionary spaces have been celebrated as sites for creatively fashioning meanings, and educating publics about cultures, places, and times other than their own. These vantages are outgrowths of the early modern era’s initial forays into collecting, rooted in Western and Enlightenment conceptions of mastery, as well as imperial desires to classify, compare, and thus make comprehensible “exotic” artifacts from around the globe. Yet collecting and museumizing have also been occasions for loss. Those peoples who had important personal and community items taken from them, oftentimes without consent and never to be seen again, experienced collecting in dramatically different ways. The ensuing material diasporas have been especially acute for Indigenous communities in the Americas, for whom collecting unfolded in tandem with settler colonialism and the attempted dispossession of tribal nations of their lands, livelihoods, languages, and beliefs.

This troubling dimension of collecting has been impressed upon me over a number of years as objects, especially Indigenous ones, have woven their way into my scholarly work on the Native Northeast. Ongoing conversations with tribal historians and community members have stressed to me that tangible things are powerful conduits that connect present-day individuals and groups with their ancestors, and with the homelands where they were placed in “time out of mind” by the Creator. They have also underscored that limiting our understandings of historical traces to written texts, particularly those composed in English, severely undermines conceptions of the past by overlooking or negating the wider set of materials that speak to historical realities and lived experiences. And they attest that the removal of certain items from traditional contexts into institutional collections has been a major concern and source of emotional pain, as well as an impetus for restorative Indigenous activism. These issues have shaped my inquiries into early Americanist collecting projects like the ones I unpack here.

These insights from tribal knowledge-keepers also present opportunities to reframe foundational narratives about materiality and collecting. In certain respects, stories about these objects ought to begin not inside colonial museums or “cabinets of curiosities,” but instead within the complex Indigenous contexts where they were originally envisioned and created. In the Native Northeast, for example, an Algonquian artisan needed to possess deep traditional ecological knowledge in order to even start the process of crafting an object. He or she would draw upon multi-generational knowledge of specific lands and waters to determine where and in which season to harvest raw materials. Once sufficient quantities had been gathered, along with the necessary tools and in accordance with protocols involved in harvesting any other-than-human resource (whether it be moose, quartz, corn, or sweetgrass), the maker would expend thought, time, and labor in fashioning the object. Others might assist in the process, as with the collective burning and hewing of mishoonash (dugout vessels), or erecting of sapling-framed and mat-covered wetuash for family dwellings. During these creative labors songs might be sung, prayers and tobacco offered, stories relayed from one member to another. While an object might be created for one purpose, over time it could be reused, repurposed, and transformed for ends different than its original function. Certain items played important roles in mortuary and memorial settings, assisting Indigenous ancestors who were traveling onward and would be reliant on objects interred with them in the earth.

By the time a “collector” laid eyes or hands upon an object—sometimes centuries or millennia after its creation—it had already been invested with thickly layered meanings, memories, and values. It was not a tabula rasa upon which any manner of interpretation could be imposed, though museum curators routinely enacted that mentality. The moment of its entrance into a formal museum or comparable repository initiated a new set of meanings, some utterly different from what had come before. Tracing transformations like these requires being attuned to a wide range of historical and cultural contexts. It requires thinking over the full life of an object, not beginning at the moment of Euro-American acquisition or museum-formation. As the case study of the “lost” Native American objects once collected—or held captive—at the AAS demonstrates, it is an undertaking still very much in motion.

Resituating the antiquarians: Nipmuc homelands at Quinsigamond and the emergence of “Worcester”

Histories of the American Antiquarian Society conventionally commence around the time of its establishment in 1812. But the emergence of the AAS ought to be situated within deeper contexts that cast into different light its acquisitive desires and behaviors. The AAS arose within a place called Worcester by Euro-American colonizers and their heirs, but known for much longer as Quinsigamond and a multitude of other Algonquian-language toponyms by Native inhabitants. This was a fertile milieu in the heart of Nipmuc country, and near the homelands of Massachusett, Pennacook, Wampanoag, Narragansett, Mohegan, Pequot, and related tribal groups. As “people of the fresh water,” Nipmucs valued the rivers and brooks that crisscrossed low hills, providing ample sources of fish, reeds and saplings for building homes, grazing areas for deer and other game, and soil amenable to planting crops like maize and squash. Native people lived in this area since time out of mind, as deep-time origin stories often put it, and across thousands of years and myriad generations they created countless physical objects to assist them in inhabiting this part of the Dawnland. Native women needed implements like hoes to tend to the cornfields and awls to sew garments, while men required arrowheads and plummet weights to hunt and fish, to take just a few examples. Some items they fashioned from nearby raw materials. Others they made from farther-flung resources for which they traded, tapping into an extensive network of relations.

Over time, as objects wore out or were succeeded by new technologies and tastes, individuals and communities set aside or replaced certain ones. Those made from organic materials tended to disintegrate over time, returning to the soil, while those derived from stone or other non-organic bases sometimes survived intact in the earth or submerged underwater. What endured over the centuries was a subset of the entirety of materials that they used to dwell, travel, conduct diplomacy and ceremony, inter deceased relatives, and raise new generations.

As Euro-American colonizers from Massachusetts Bay and other expansionist colonial endeavors developed settlement plans for the Quinsigamond area in the mid-seventeenth century, they entered not into a “howling wilderness” but a thoroughly inhabited and known Indigenous place. Territorially acquisitive colonists angled to attain land grants and negotiate deeds with local Indigenous leaders, a much-contested history in itself. Colonization faltered in its earliest stages, thwarted by Indigenous pushback in the central Massachusetts region during the conflict sometimes called King Philip’s War (1675-1678). It was in the aftermath of that crisis, which resulted in painfully constrained circumstances for the Indigenous people and nations who survived its violences, that colonization accelerated, leading to the growth of a New England town around Quinsigamond. It is important to recognize that this conflict, as well as subsequent Northeastern “Indian wars,” did not sweepingly remove or destroy Indigenous populations. Many Algonquians endured in the region, carving out new livelihoods for themselves in an array of free and sovereign settings, as well as under the strictures of unfree labor and colonial surveillance.

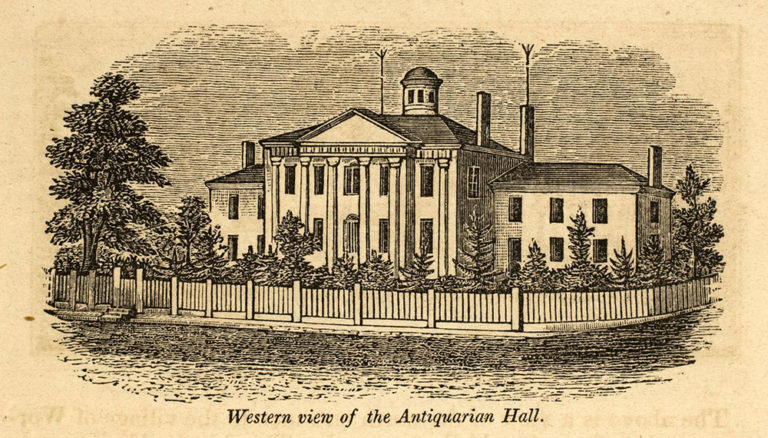

How the American Antiquarian Society wound up situated in the midst of Nipmuc country was a consequence of geographic strategy by its Euro-American founders in the early American Republic. With the military devastations of the Revolutionary War relatively fresh in mind, founders were wary of selecting an exposed coastal location for their new venture, such as Boston or Newport, which might endanger its anticipated collections. As they organized in 1812 they looked inland for a suitable venue, as Isaiah Thomas had done with his printing operations during wartime, and chose Worcester. The AAS was established there with a conception of being a protective haven for precious historical treasures that might otherwise be lost to the ravages of social upheaval and time.

While the Society was the lone institution of its kind in early nineteenth-century Worcester, it had counterparts throughout New England and the mid-Atlantic. The Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston, the East India Marine Society in Salem, the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, collegiate museums and “cabinets” created at Harvard and Yale, and other sites similarly fashioned themselves as repositories for heritage items and/or centers for learned study. They rose to prominence during a pivotal moment when the newly independent United States was seeking to establish historicity of its own to rival that of Europe, and to set it apart from the “Old World.” Collecting historical objects, texts, and other Americana was critical to nascent projects of nation-building and myth-making. Certain of these institutions shared members who traveled in elite circles, but they also cultivated a genteel sense of competition, striving to lay claim to the most distinctive, illustrative, or extensive sets of materials.

Leaders at the AAS made Indigenous collecting central to its mission from the very outset. The initial cohort of antiquarians and their successors prized “aboriginal” artifacts as integral to their studies of early American pasts, and potentially useful in helping differentiate their enterprise from peer institutions. They did not wait passively for donations to trickle their way, but instead took proactive steps by repeatedly issuing calls for donations. Members, affiliates, and residents of the region began to view the AAS as a logical repository for “finds” they made, and responded by shipping Native objects to Worcester or delivering them in person. Because of its central Massachusetts location, the Society attracted a sizable number of objects from the immediate surroundings of Nipmuc and other Northeastern Algonquian homelands. As time went on, Indigenous objects from Midwestern, Southeastern, and eventually Western/Pacific areas also came into the collections. While the growing collection’s center of gravity lay in North American holdings, a number of items from Peru and the Yucatán also attained places of prominence in Worcester.

Once objects entered the Society’s chambers, their meanings evolved. They were still fully Indigenous objects, meaningful to tribal descendant communities albeit geographically dissociated from them. But upon passing into the Society’s hands, other forms of interpretation became applied. Inside they were curated and displayed in a cabinet, with handwritten labels affixed to them. AAS affiliates William A. Smith and Stephen Salisbury III overhauled these displays in the 1860s to reorganize Native American items into a series of glazed display cases. Many labels described them as generically “Indian” rather than tagging them with information about temporally, geographically, or socially specific histories.

While there was not a monolithic narrative that the AAS applied to all Indigenous objects, common themes did emerge. Frequently they were marshaled into the service of narratives about colonial conquest of Indigenous people, or used to support notions of Indian exoticism. Most problematically, they were employed as tangible evidence of Native pasts, but not presents: part of larger New England and American mythologies about alleged Indigenous decline, assimilation, and/or disappearance. It was no coincidence, after all, that robust collecting transpired in areas where colonizers and their heirs were directly engaged in the territorial dispossession of Native nations, and were intent on legitimating their claims by taking, “owning,” and exhibiting Native materials from those very grounds. This was a cultural dimension of settler colonialism: amassing Native artifacts to indicate that a previous people had passed away, making room for “settlers” who could then become the custodians of those “relics.”

The Worcester antiquarians attempted to be systematic in registering the items that came to the AAS. The librarian recorded both textual and material accessions in a donation book. This book (actually consisting of several folio volumes and loose papers, now housed in the AAS archives) documented items that were accessioned, names of donors if known, dates of arrival, and sometimes other contextual information. “An Indian Gouge, found in Worcester and presented by George Trumbull, Junior of Worcester,” read one entry from June 25, 1832, typical in its terseness. While this record-keeping system did give a semblance of logic to the growing collection, it was a highly limited framework. The information entered was partial and prone to errors, generally lacking the kinds of provenance that later generations of cataloguers would consider essential. Where, specifically, within Worcester was the gouge contributed by Trumbull unearthed? Was it simply “found,” lying within an exposed surface, or did Trumbull actively dig for it? If the latter, how deeply within the soil layers did it lie? Were other objects located near it?

The entry remained silent on those critical elements. Instead, it prominently foregrounded the Euro-American donor as a salient feature. Furthermore, this system imposed Euro-American logics on the growing array of materials, not Indigenous ones that likely would have described and organized these items very differently. The blanks and omissions in this form of record-keeping also affected other objects collected in period museums, especially those associated with non-elites, women, people of color, and children. Distinctive about Native items was the fact that they were sometimes treated as extensions of natural history, or as timeless traces, rather than clearly demarcated as the belongings of human beings from particular social, cultural, or geographic contexts. Certain accession information was also distilled into the published Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, allowing members who might not be able to visit the cabinet in person to cultivate a sense of its expanding contents. Vital to the entire mechanism were restrictions that encouraged items to enter the Society, but prevented their being loaned out, with few exceptions.

Unsettling acquisitions: Collecting in Native space

Each laconic archival snippet about an “Indian” object can be a lens onto complex tribal histories and interactions with colonizers. Unfolding these requires putting the AAS records into extensive conversation with other sources, in ways that sometimes bring to light painful happenings. To take just one example, in October 1816, a small bottle arrived at the AAS cabinet. It came from Natick, a town in eastern Massachusetts and the historical location of one of the so-called “praying towns.” In the mid-seventeenth century, a series of these towns was established within Native homelands under the oversight of Puritan missionary John Eliot, with the goal of gathering in and acculturating prospective Algonquian converts to English ways and Protestant Christianity. Despite these designs the “praying towns” were never fully Anglicized or Christianized spaces. Their Native inhabitants strategically combined traditional Indigenous lifeways and cosmologies with newer Euro-American ones, and remained connected to wider networks of kin and homelands resources beyond the contained boundaries of Natick proper. Following King Philip’s War, Native inhabitants of Natick gradually found themselves dispossessed of their land base by Euro-American neighbors, as historian and Native American Studies scholar Jean O’Brien (also a White Earth Ojibwe member and former AAS fellow) has minutely documented. By the time robust collecting was underway at the AAS, Natick-area Natives were enmeshed in basic struggles to survive amid a tide of Euro-colonial expansionism in Massachusetts.

The significance of a bottle from Natick might not be fully apparent at first glance. But additional information about its nature and circumstances was conveyed in a published local history. In his History of the Town of Natick, Massachusetts (1830), William Biglow extensively discussed cemetery areas in Natick, including an Indian burying ground close by the Charles River, a critical waterway for generations of area Algonquians. He noted that local (white) residents had repeatedly disinterred Native items as well as human remains in the course of agricultural and construction projects. In some instances the human remains were reinterred. In others they likely were not. During one of these episodes workmen came across funerary objects: a “small junk bottle was discovered with a skeleton, nearly half full of some kind of liquid; but the lad, who dug it up, emptied it before the quality of its contents was ascertained.” This now-empty bottle—likely made of thick, strong glass, as Biglow’s term “junk” can mean in an archaic/technical sense—along with “several other Indian curiosities,” was eventually conveyed to “the museum of the Antiquarian Society in Worcester.” Biglow himself appears to have been the donor.

At this very earliest moment of “collecting,” disruption was already part of the process. Yet to Biglow and myriad other Euro-Americans, extraction of Native artifacts from such grounds and donation to places like the AAS likely appeared to them admirable efforts at preserving a bygone people’s traces, rather than as desecration of the burial places of ancestors connected to living descendants. This is not merely speculation. Biglow was indubitably convinced of the decline and vanishing of Native populations. The advertisement to his History, announcing its raison d’être, commented: “it is thought that many will be desirous to know, as far as can be ascertained, the circumstances which accompanied the gradual decrease and final extinction of the first tribe, that was brought into a state of civilization and christianity, by a Protestant missionary.” In his eyes an extinguished people could have little interest in or claim to items like a buried bottle, nor the remains interred around it.

Natick’s prominence within the “praying town” context, coupled with regional hagiography about the “Apostle” Eliot, may have made it a magnet for collecting in this era. Numerous material artifacts and human remains associated with Natick-area Natives were disinterred by Euro-Americans over the years. Some came to reside in a series of natural history and historical organizations in Natick itself, construction of which further disturbed sensitive Native grounds. The AAS received at least one other item from Natick: a smooth, dark-colored stone, about the size of a fist, incised on one side with circular shapes apparently used for casting buttons, and on the other with an image of a turtle. It was described in the AAS Proceedings of 1868, in the middle of a list of Indigenous artifacts and ancestral remains from the Mounds areas and other regions, as a “Stone Mould, found in Natick, Mass., supposed to have been used by the natives in making lead ornaments.” The accession information sheds little light on the context from which this marked stone emerged. Was it removed from a burial or other sacralized ground? Textual records gave no direct indication that this was the case, but nor did they unambiguously rule out that possibility.

In situations like these, and especially those involving Indigenous ancestral remains, I hesitate about whether to narrate them at all—and if so, how to do so without inflicting damage. Focusing on them runs the risk of re-inscribing violence against Indigenous bodies, objects, and places. It can recapitulate centuries of problematic scholarly practices that have privileged such voyeurism under the guise of scientific inquiry and dehumanized its “subjects”; or give the impression to readers that they are grotesque spectacles to behold and scrutinize. It is never my intention to do so. In fact, I have chosen to be reticent about these details (though they are amply present in the archives), and to omit visual representations that would contribute to such violations, being cognizant that a digital publication like Common-place can make such representations circulate all the more widely.

At the same time, there is value in acknowledging and documenting the nature and extent of early Euro-American trafficking in Indigenous artifacts and remains. Current personnel and users at institutions like the AAS oftentimes have little sense of the scope and gravity of these “collecting” projects. Meanwhile, the repositories that eventually attained these items (as discussed below) may have only partial information about the objects’ origins and purposes. These historical contexts can be especially vital to recover in the twenty-first century as tribal communities and repositories navigate the dynamics of repatriation—the return of certain types of materials to descendant communities. Following passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in 1990, the landmark U.S. federal legislation (effected after generations of community-based activism) that provides for inventorying and eventual return of remains and objects, many repositories have been immersed in detailed, complicated, consequential research to determine appropriate paths forward.

The range of potentially NAGPRA-sensitive objects once held at the AAS was extensive, stretching well beyond the bottle from Natick. Human remains, funerary items, ceremonial objects, and similar materials constituted a significant portion of the holdings at the AAS in the nineteenth century. Consider a handful of examples gleaned from the Society’s institutional records and published in Proceedings. In August 1834, George C. Davis donated three human crania, disinterred from historical Pocumtuck homelands in the Greenfield, Massachusetts, area. This stretch of the Kwinitekw/Connecticut River Valley had been a dynamic Native thoroughfare and crossroads for thousands of years, connecting Algonquian inhabitants to Native relations across the Northeast. More recently, it had become a region with a problematic history of rampant antiquarian “harvesting,” as Abenaki scholar Margaret Bruchac and others have documented. Judging from the terse entry in the AAS donation book, it appears that only the trio of crania arrived in the Society’s cabinet. The very process of donating may have caused the disarticulation and attendant disruption of Indigenous ancestors’ bodily integrity, since Davis may have been mindful of transportation costs or the Society’s limited storage space.

In 1843, a correspondent donated several items taken from Onondaga burials in Haudenosaunee/Iroquoian homelands. (Over the centuries the Onondaga Nation has confronted numerous disturbances, and has been actively working on a number of repatriation efforts to redress damaging histories of collecting.) Numerous ancestral remains and associated items from the Mounds of the Midwest—ochre, ornaments of silver, copper, mica—were removed from the massive earthworks and donated as well. Some of these sites had likely only narrowly avoided desecration in 1835 when Christopher Columbus Baldwin, librarian of the AAS (and namesake of the “New World” colonizer), was dispatched to the Ohio region by the council to conduct research. “What I particularly want and am desirous of procuring is a collection of skulls,” he commented several years earlier to a correspondent. “I want the skulls of that unknown forgotten people who built the mounds and forts, and inhabited the country before the present race of Indians.” He was articulating a then-commonplace assumption that the “Moundbuilders” were not ancestors of contemporary Native Americans, a premise (now widely challenged) that seemed to confer moral legitimacy on Euro-Americans’ intrusive probings. Baldwin died en route in a stagecoach accident, permanently curtailing his personal collecting aspirations but not those of the learned society that he represented.

The Euro-Americans who removed these items from the earth considered them suitable specimens for understanding the deep past, or, alternatively, valued them as exotic curiosities. In their eyes, separating these materials from the places where they had been interred was not problematic. But Native descendant communities, whose spiritual systems relied on the proper treatment of ancestors and burial materials, would have viewed such disinterments as massively disruptive to the spiritual and social fabric. A critic might have countered that there was nothing singular about the Indigenous remains and funerary items that were amassed. The AAS also acquired human remains of a British grenadier disinterred from Bunker Hill, after all, and a cane purportedly hewn from the casket of Isaiah Thomas. But while such a critique acknowledges that occasionally white individuals were subject to invasive treatment and antiquarian display, it would gloss over the honorific manner in which Thomas (at least) was marshaled into the service of memento-making. It would also ignore the much larger scale of collecting that targeted Indigenous peoples, and eclipse the profoundly different power dynamics in operation during Euro-American acquisition of Indigenous materials, given the direct links to processes of territorial dispossession and racial marginalization.

Not every item in the cabinet emerged from these highly appropriative practices, certainly. Without delving into the minutiae of dozens of objects, it appears that at least some were attained through trade or other forms of consensual economic exchange. Others likely arrived in the hands of AAS donors via reciprocal practices of gift-giving and diplomacy, or through marketplace interactions in which skilled Indigenous artisans produced certain kinds of wares specifically for consumption by Euro-Americans. Using the resulting income to support themselves and their families in an era of massive land and resource loss, these Indigenous producers made strategic decisions to circulate certain kinds of handcrafted objects into private and public American venues. Sometimes they deliberately catered to aesthetic preferences of non-Native consumers in their basketry, quillwork, birchbark, woodcarving, and other media, fashioning eye-catching goods with complicated hybrid qualities. It is vital to account for these other potential routes of acquisition, since they can attest to the agency, adaptability, and resilience of Native people amid rising tides of settler presence and pressure. Yet as Ruth Phillips, the scholar of First Nations/Canadian material culture, has indicated about this spectrum of object transit, they were not necessarily unencumbered by larger concerns of colonialism and marginalization of Indigenous populations.

A further essential twist in the story of the Society’s collecting is that some of its textual accessions directly refuted American mythologies about Indian primitivity and vanishing. In 1832, the Society acquired copies of The Cherokee Phoenix, a bilingual (English/Cherokee-language) periodical edited by Elias Boudinot in New Echota and partly composed with the Cherokee syllabary devised by Sequoyah. Visitors to the AAS who consulted issues of the Phoenix would have encountered robust tribal critiques of U.S. expansionism in the age of attempted Indian removal in the Southeast. As they turned its pages, they would have been compelled to reflect on the carefully typeset evidence of a tribal community that was embracing technological innovation, and indigenizing print culture to serve the communicative and political needs of the Cherokee Nation’s citizens in a moment of pervasive transformation. The Society also added to its shelves the landmark Worcester v. Georgia Supreme Court decision of the Marshall trilogy in 1832, which spoke to contemporary efforts to assert sovereign powers and clarify jurisdictional lines between tribes, states, and the United States. And the AAS accessioned an 1834 compendium of grievances articulated by the Mashpee (Wampanoag) tribal community, engaged in a protracted struggle with Euro-American neighbors and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Accessions also included a range of texts authored by Native intellectuals and activists, such as an execution sermon for the Wampanoag Moses Paul, delivered in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1772 by the Mohegan minister Samson Occom and published in multiple editions. Indigenous authors like Occom strategically adapted Euro-American print conventions to express their own outlooks, histories, and futures, and pushed back against mentalities and policies that endeavored to erase them. Yet as Michael Kelly, head of Archives and Special Collections at Amherst College, who is currently overseeing development of a large collection of Native American literature, has pointed out, there is a difference between institutions’ collecting of printed multiples—published texts expressly designed by their authors to be widely read—and the collecting of material heritage objects, many intended to be kept within the tribal community that produced them, yet taken through coercion or without consent. All of these types of items shared space in nineteenth-century Antiquarian Hall, however uneasily.

Rethinking the cabinet: Deaccessioning at the AAS and the establishment of the Harvard Peabody Museum

The Worcester antiquarians’ enthusiasm for objects waxed and waned over the course of that century. As late as 1868 the Society clearly expressed desire to foreground Indigenous “specimens,” asserting that the AAS “should possess as perfect a collection as possible of all the portable monuments of the customs, the intellectual conceptions, and manual skill of the original inhabitants of this continent.” (The curious phrasing of “portable monuments” suggested antiquarians’ willingness to dislocate Indigenous items from their contexts, sometimes by hundreds or thousands of miles, even when the communities that created them expressly resisted those removals.) Yet even in its early years the Society faced challenges in curating and displaying its material holdings. A visitor to the Society in the 1820s reported disappointment at the state of affairs, particularly the dearth of reliable staffing to ensure order and access:

On requesting a view of the cabinet of curiosities and antiques, the stranger is informed that no admission has been allowed for more than a year. There are collected all the interesting specimens of minerals, arms, utensils, dresses, ornaments, &c. which have been forwarded to the Society from different parts of the country, with which the world have been made acquainted through their publications; but on account of the confused situation in which they are allowed to remain, they are considered unfit for exhibition.

For decades the Society struggled to find sufficient space for its multifarious collections, outgrowing one location and moving to a new building, or requiring additions, several times. Members became concerned about the fragility of “perishable” artifacts—presumably those containing organic components vulnerable to light, insects, mold, and other environmental factors—and debated whether the Society could be a proper custodian. The intellectual underpinnings of the Society also morphed and led some antiquarians to view “ethnological” objects as peripheral to the mission of an institution increasingly focused on being a library. Maintaining the cabinet seemed at odds with desires to maximize resources for the preservation and study of texts. They worried that by remaining so capacious, the Society was losing a distinctive mission and becoming hampered as a literary center for early Americana.

As the Society reassessed its collecting purview, a new institutional development to the east presented alternative possibilities for handling the objects. George Peabody, a Danvers-born financier who made his wealth in dry goods and British banking, donated $150,000 to launch a museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His philanthropic bequest established the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (PMAE) at Harvard University in 1866. Additional bequests established institutions like the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University, the trajectory of which bore strong similarities to the Harvard enterprise. By 1877 a purpose-built, fire-resistant building on Divinity Avenue in Cambridge housed the nascent museum collections, which had previously inhabited Boylston Hall on campus. Over time its contents encompassed artifacts from the Americas, north and south, as well as from across the globe. Located less than fifty miles east of Worcester, the PMAE cultivated ties to existing networks of influential Euro-American collectors and antiquarians. The PMAE’s board of advisors included the heads of learned societies such as the Massachusetts Historical Society and the AAS, while its longest-serving director was Frederic Ward Putnam, an active AAS member.

No Native communities were represented on the board or museum staff, even as the PMAE took root within ancient and ongoing Native space. It was in Cambridge, after all—in the midst of Massachusett and Wampanoag territories, and alongside the same river that flowed through Natick—that an Indian College at Harvard had arisen in the mid-seventeenth century. Although a small number of young Native men became Harvard scholars in that era, institutional support for Native higher education soon dropped off and the Indian College’s history had become nearly invisible to collegiate affiliates by the time of the U.S. Civil War. Moreover, nineteenth-century mentalities about who constituted learned “authorities” or legitimate members of an elite space like Harvard were strongly racialized, leading to a slate of Euro-American museum advisors who strenuously believed they could accurately comprehend and speak to the material heritages of diverse peoples. Anthropologists of this period sometimes recognized the importance of Native community members as “informants,” but by and large did not envision them as scholars, critical commentators, or peers.

The early evolution of the PMAE was heavily influenced by the tenure of Frederic Ward Putnam. His interests in “Indian” researches ran deep, encompassing work on New England Algonquian contexts, the Midwestern and Southeastern mounds, and other sites. His intensive use of Native human remains for purposes of study and illustration manifested enormously problematic attitudes toward Indigenous materials and ancestors—harvesting them as “specimens” and subjecting them to public display—though at the time he and his audiences considered them appropriate vehicles for scholarly inquiry. Museum settings like the PMAE were not the only academic venues in which troubling dynamics like these played out. American medical schools also sought human remains for anatomical study, and turned disproportionately to people of color, immigrants, the poor or criminalized, and other socially marginalized groups for their “supplies,” as Michael Sappol has noted. In the contexts of museums and the emerging medical profession, the very foundations of “study” and “knowledge” often rested on the appropriated bodies of those classified as “other” and denied social power. (A salient distinction was that medical settings often treated the remains as disposable, whereas museums more often approached them with notions of preservation.) Overall Putnam aspired to systematize studies of the past and of other peoples. In an 1889 description of the PMAE solicited for the AAS’s Proceedings, he remarked, “The day had gone by when collections of bric-a-brac were designated museums.” (Perhaps he had the catch-all quality of the AAS cabinet in mind.) Instead, he wished to support “the science of man.”

In his directorial capacity Putnam seems to have encouraged the transfer of objects from the AAS to the PMAE. At the very least he was receptive and took an active role at the invitation of the AAS Council. Following a slight delay due to his role overseeing the anthropological exhibitions at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago of 1893, Putnam perused the cabinet and selected materials for transfer to Harvard. The remainders were to stay at the Society, or be offered to the Worcester Society of Antiquity. (Today this institution, housed at the corner of Elm and Chestnut Streets in the city, is known as the Worcester Historical Society.) While the details of these deliberations and transfers are documented only partially, it appears that the parties involved believed they would conveniently address two problems: the AAS’s struggles to house and manage its cabinet, and the young PMAE’s desires to build up its own collections. In several stages in the 1890s and early 1900s, the AAS packed up batches of Native American and other artifacts, de-accessioned them, and had them carted east to Cambridge for deposit at the PMAE. The AAS profited from these transfers, receiving at least $400; these funds it used to purchase reference books. In certain respects these Indigenous objects had become commodified, attaining value in a marketplace governed by Euro-American elites, while removing them yet another step from Indigenous settings.

When these objects physically left Worcester, they began to recede from institutional memory at the AAS. But the objects themselves remained, and their lives continued in a museum devoted to comparative study of global cultures. The PMAE’s own history belongs to a larger story about the professionalization of anthropology as an academic discipline, and the consolidation of university-affiliated museums for teaching and research purposes. In addition to soliciting and accepting donations, the PMAE built its collections by sponsoring “fieldwork” expeditions to locales like the American Southwest with the express goal of bringing back large quantities of items for comparative research. These practices held consequential implications for Indigenous communities that became targets for collection building, often without full knowledge of which artifacts and traditional practices were being removed or recorded, and ultimately represented to external audiences.

Still present: Indigenous survivor objects and new approaches to collections

Today large numbers of the Indigenous items formerly held at the AAS are still very much in existence at the PMAE. The majority of them lie in controlled storage rather than on display for the public. Most have not been used in substantive scholarly inquiries, though a few have occasioned incisive revisitations of their meanings. Because my own work centers on the Native Northeast and colonial New England, I have been particularly interested in those with ties (real or purported) to this region , such as a beaded textile long referred to as “King Philip’s sash.” This delicate item occasioned a closer look by Peabody staff members, in conversation with Elizabeth James Perry of the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe, who has done extensive cultural heritage and repatriation work in the region. Their investigations brought together anthropological and tribal perspectives, and the resulting multivocal analysis suggested that the red fabric sash, decorated with dark beads, may bear more similarities to Southeastern or Wabanaki material practices than to seventeenth-century Wampanoag ones. These reassessments have raised the question of why antiquarians might have felt invested in ascribing the sash to the famous Wampanoag sachem and resistance leader of the seventeenth century named Metacomet/King Philip—perhaps desiring to bolster their own reputation by claiming an object associated with a prominent Native figure instrumental in formative conflicts with early colonists.

A bag described by early collectors as having belonged to Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, a 1665 Wampanoag graduate of the Harvard Indian College, has appeared under closer scrutiny to be fashioned from fibers and weaving techniques typically arising from West African contexts. These material evidences suggest possible Afro-Indigenous connections, exchanges, or transatlantic influences. Alternatively, they may open up complex histories of misattribution and mythologizing, with the antiquarians again invested in claiming possession of an item characterized as the property of a prominent Algonquian individual. And the dark stone with button-molds and an incised turtle from Natick may have been used for casting garment-fasteners in a powerfully hybrid or syncretic form of Indigenous self-fashioning, Diana DiPaolo Loren has suggested. Given longstanding traditional meanings of turtles in Algonquian oral traditions and belief systems, it may also be possible that turtle castings were mobilized, traded, and valued for purposes beyond clothing.

When I visited the PMAE’s collections and archives in summer 2016 during a multi-day visit facilitated by curators, archivists, and additional staff members, I was certainly compelled by the items described above. Their enduring ambiguities invite much further consideration, especially by diverse descendant communities whose own knowledge-keeping practices may shed new light on these objects’ meanings, and on the pathways for their future treatment. Yet I was equally interested in more quotidian ones: a fragment of a soapstone bowl, for instance, carved from a steatite formation that Algonquians knew well, and likely used for cooking. There was also a fishing plummet, employed for harvesting riverine or coastal species from well-traveled taskscapes in “wet homelands”; a purse embroidered with delicate quillwork in floral and geometric patterns, with tassels of animal hair and sewing thimbles reworked into decorative and sonic elements, possibly created for use in the tourist trade; and many others. Each of these objects stands to illuminate Indigenous histories and the relationships between Native people and Euro-American colonizers, in ways that may not be fully evident in the documentary records on which so many scholars rely.

Unfolding these stories requires careful, creative methodologies that look beyond the labels applied by antiquarians. A “decolonizing” approach also necessitates conversations with present-day Indigenous descendant communities, and the foregrounding of Indigenous epistemologies and forms of knowledge-making. It involves recognizing that “research” itself is attended by uneasy baggage, such as the differential kinds of access to collections that Native and non-Native investigators sometimes experience. What I have sketched in this short piece is a roadmap rather than a fait accompli. These are long-term agendas, to be realized over years rather than weeks or months, and they hinge on cultivation of respectful, reciprocal relationships as much as on technical investigative skills.

Ideally this work is collaborative and multivocal since pertinent documents, objects, scholarly perspectives, and traditional knowledge exist in a multitude of sites, and require tremendous effort to bring together in systematic ways. It respects the fact that certain kinds of community deliberations and insights are considered private or internal, and not appropriate for academic analysis or public discussion. It proceeds with the understanding that present-day tribal communities carry substantial burdens in the restorative labors they take on in areas like education, language revival, wellness, and environmental stewardship. Historical research shares space and energy with these vital projects, and is intertwined with these more holistic community concerns. When Euro-American repositories that possess considerable resources can make materials relevant to cultural heritage more readily accessible, it can help open the way for Native-centered work to proceed. Sometimes these processes can be contentious, as I have come to understand at the three New England institutions where I have been a student or faculty member (Harvard and Yale Universities, and Mount Holyoke College). Each has a long history of collecting that has occasioned debates over repatriation, as well as the appropriate handling of Indigenous materials that remain in storage or on display. But these are necessary struggles that involve reckoning with foundational issues of identity, ethics, and relationships.

Institutional histories of the AAS typically have acknowledged the historical amassing of Indigenous objects. Yet they have tended to treat this corpus as an aberration, an over-extending of the Society’s mission that was ultimately corrected by transmitting them to other repositories and re-focusing the collection on texts and images. None of the Society’s published accounts have yet reckoned directly with the nuances of these objects’ complicated transits or their long afterlives. Nor have they deeply reflected upon the ethics involved—both historically and in the present day—or the array of tribal descendant communities that in a sense are still tied to the institution as a consequence of this difficult past. Even certain recent institutional histories have characterized the collecting of Indigenous human remains in an almost flippant manner, addressing the matter of a “Kentucky mummy” as a macabre curiosity rather than bringing more substantive critical sensibilities to bear upon it. These narratives deserve to be revisited and amended, especially in light of growing support at the AAS for scholarly work in Native American and Indigenous Studies, and for research done by Native community members.

The Indigenous objects that once resided in early American learned societies, libraries, and museums present powerful opportunities for institutions in New England and the United States, not to mention Europe, to reflect on their own entanglements with centuries-long patterns of dispossession and settler colonialism. They also present occasions for reckoning with responsibilities that the original collecting sites still may bear to tribal nations, even if the objects themselves are no longer within their purview in a legal sense. To put it another way, the AAS was a reason why so many Native objects were dislocated, and a reason why they entered a system of appropriation that is ongoing. Optimally, such institutions can move beyond past generations’ constrained views of “Indian curiosities” to build collaborative relationships with contemporary tribal communities, who maintain complex understandings about their own material heritages. It is time to make space for their knowledge and interpretative insights at the center, rather than relegated to the margins or editorial afterthoughts. These communities, after all, are often involved in parallel research and curating of tribal-run museums, such as the Hassanamisco Museum of the Nipmuc Nation, the Tantaquidgeon Museum of the Mohegan Tribal Nation, the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation Museum, the Niantic/Narragansett-run Tomaquag Museum, the Mashpee Wampanoag Museum, and others. These places act as caretakers for objects not in order to isolate static views of history, but to bind together past, present, and future in support of the endurance of Native people and nations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the American Antiquarian Society (through a National Endowment for the Humanities long-term fellowship in 2016), as well as by a faculty research grant from Mount Holyoke College and Mellon curricular development support from the college’s Nexus program. I am grateful to librarians, archivists, curators, and preservationists in many areas of the Northeast for access to collections and insights on these histories and future possibilities. I am particularly indebted to tribal community members for ongoing conversations about these matters, such as Elizabeth James Perry (Aquinnah Wampanoag) and Melissa Tantaquidgeon Zobel (Mohegan); to members of the Five College Native American and Indigenous Studies faculty group; and to Mike Kelly at Amherst College’s Archives and Special Collections for intellectual grounding in futures of collections. I am also grateful to Kelly Wisecup, Drew Lopenzina, Patricia Rubertone, and Scott Stevens for taking part in a panel on “Native American Material Histories” at the 2016 Omohundro Institute for Early American History and Culture conference in Worcester.

At the AAS, Nan Wolverton shared helpful information about material culture and institutional collecting practices, while Kimberly Pelkey and Paul Erickson helped me think through several dimensions of Native Studies as it pertains to this repository. During my fellowship, Pelkey (Nipmuc), head of Readers’ Services, developed the digital portal From English to Algonquian: Early New England Translations. AAS fellows in residence during winter-spring 2016 generously shared feedback on my work-in-progress. At the PMAE, Meredith Vasta, Katherine Myers, Patricia Capone, and Diana DiPaolo Loren shared insights and sources, while Ethan Lasser at the Harvard University Art Museums has been an interlocutor about early Americanist collecting. Staff at the Natick Historical Society informed my understandings of that space. At the Mount Holyoke College Art and Skinner Museums, Aaron Miller, Ellen Alvord, and Kendra Weisbin have shaped my thinking on historical collecting and new directions, as have students in my “Afterlives of Objects” seminar. My research assistant Allyson LaForge helped me work through collections lists and decolonizing avenues. Common-place editorial staff, Ellery Foutch, and Sarah Anne Carter assisted with development of this piece, while Jackie Penny facilitated access to AAS images.

Further Reading

For an overview of Nipmuc homelands and historical contexts, written by current Nipmuc Nation chief and researcher Cheryll Toney Holley, see “A Brief Look at Nipmuc History,” in Dawnland Voices: An Anthology of Indigenous Writing from New England, ed. Siobhan Senier (Lincoln, Neb., 2014): 404-410. Institutional archives are critical sources for reconstructing objects’ movements and changing interpretations over time. Among other sources, at the AAS I drew upon the series of donation books in the AAS archives. For published accounts of developments at the AAS in its formative years, see successive volumes of Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, which have been partially digitized. At the PMAE, I drew upon copies of the ledger books of accessions; individual object accession files; and Frederic Ward Putnam papers, as well as the online catalog. The objects mentioned in the final section are Peabody numbers 90-17-10/49333 (sash attributed to King Philip); 90-17-50/49302 (bag attributed to Cheeshahteaumuck); 10-47-10/79966 (steatite fragment); 10-47-10/79968 (fishing plummet); 10-47-10/79953 (stone with incised turtle); 90-17-10/49322 (small pouch with quill decoration).

Histories of collecting, museum-building, and concomitant disruptions to Native communities have generated a large body of literature. For overviews and Northeast-specific considerations, see Kathleen Fine-Dare, Grave Injustice: The American Indian Repatriation Movement and NAGPRA (Lincoln, Neb., 2002); Patricia E. Rubertone, Grave Undertakings: An Archaeology of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians (Washington, D.C., 2001); Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead (Chicago, 2010); Samuel Redman, Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums (Cambridge, Mass., 2016). On appropriations of human remains for anatomical study, see Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, N.J., 2002). On Putnam’s roles in shaping anthropological approaches to Indigenous subjects, see Steven Conn, chap. 5, “The Art and Science of Describing and Classifying: The Triumph of Anthropology,” in History’s Shadow: Native Americans and Historical Consciousness in the Nineteenth Century (Chicago, 2004). For discussion of Indigenous ancestral remains with direct ties to the AAS, see Judy Kertesz, “Skeletons in the American Attic: Curiosity, Science and the Appropriation of the American Indian Past” (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2012). On Indigenous participation in the “tourist trade” through salable material objects, see Ruth B. Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700-1900 (Seattle, 1998). On early American collecting at a nearby Massachusetts institution, which also encompassed Indigenous objects, see Patricia Johnston, “Global Knowledge in the Early Republic: The East India Marine Society’s ‘Curiosities’ Museum,” in East-West Interchanges in American Art: “A Long and Tumultuous Relationship,” eds. Cynthia Mills, Lee Glazer, and Amelia Goerlitz (Washington, D.C., 2012): 68-79.

Most institutional histories of the AAS have downplayed the role of objects: see A Society’s Chief Joys: An Introduction to the Collections of the American Antiquarian Society, with a foreword by Walter Muir Whitehill (Worcester, Mass., 1969), esp. 10, 17, 18; Philip F. Gura, The American Antiquarian Society, 1812-2012: A Bicentennial History (Worcester, Mass., 2012), esp. 39-42, and In Pursuit of a Vision: Two Centuries of Collecting at the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, Mass., 2012), esp. 26, 51, 73. For a retrospective consideration of the role that objects played and details on how they were situated, see Mary Robinson Reynolds, “Recollections of Sixty Years of Service in the American Antiquarian Society,” Proceedings 55 (1945). Several objects that remain at the Society have been researched by Nan Wolverton: see “On High: A Child’s Chair and Mather Family Legacy,” Common-place.org 13:4 (Summer 2013), and “An Old Vial of Tea with a Priceless Story: The Destruction of the Tea, December 16, 1773,” Past Is Present: The American Antiquarian Society Blog, Dec. 14, 2014. On textual productions by Native writers, intellectuals, and critics, some of which were being collected at the AAS at the same time as Native objects, see Phillip H. Round, Removable Type: Histories of the Book in Indian Country, 1663-1880 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2010). Round’s blog, The Repatriation Files: Conversations on Native American Cultural Sovereignty, engages ethical and historical dimensions of collecting. On histories of collecting related to Samson Occom, see Paul Erickson, “Moses Paul to Samson Occom: Rediscovering a Treasure,” Past Is Present: The American Antiquarian Society Blog, 20, 2015. On Christopher Columbus Baldwin’s pursuits and contexts, see A Place in My Chronicle: A New Edition of the Diary of Christopher Columbus Baldwin, 1829-1835, Jack Larkin and Caroline Sloat (Worcester, 2010).

On the history of the PMAE, see Rubie Watson, “Opening the Museum: The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,” Occasional Papers I, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, from Symbols (Fall 2001); Frederic Ward Putnam, “The Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology in Cambridge,” in Proceedings of the AAS, new series, Vol. VI, April 1889-April 1890 (Worcester, Mass., 1890), 180-190. On the transfer of certain objects from the AAS to the PMAE in 1895, see “Report of the Librarian,” in Proceedings of the AAS, new series, Vol. X, April 1895-October 1895 (Worcester, Mass., 1896), esp. 71-73. On museum-building in other parts of Harvard and nationally, see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, Ivan Gaskell, Sara Schechner, and Sarah Carter, Tangible Things: Making History through Objects (New York, 2015); Steven Conn, Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876-1926 (Chicago, 1998).

On new assessments of selected objects once held at the AAS and now at the PMAE, see T. Rose Holdcraft, Elizabeth James Perry, Susan Haskell, Diana DiPaolo Loren, and Christina Hodge, “A Rare Native American Sash and Its Paper Label ‘Belt of the Indian King Philip. From Col. Keyes.’ A Collaborative Study,” in European Review of Native American Studies 21:2 (2007): 1-8; Claire Eager, “Settlers, Slaves, and ‘Salvages’: The American Fabric of History and Value in an African ‘Indian’ Bag,” Tempus: The Harvard College History Review V:1 (Fall 2002); Diana DiPaolo Loren, chap. 11, “Casting Identity: Sumptuous Action and Colonized Bodies in Seventeenth-Century New England,” in Rethinking Colonial Pasts through Archaeology, eds. Neal Ferris, Rodney Harrison, and Michael V. Wilcox (New York, 2014): 251-267.

For a historical assessment of the “vanishing” Indian trope in New England, see Jean O’Brien, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England (Minneapolis, 2010), as well as Dispossession by Degrees: Indian Land and Identity in Natick, Massachusetts, 1650-1790 (New York, 1997). Emerging conversations in the field of Native American and Indigenous Studies have stressed the need for collaborative, respectful, authority-sharing research that connects scholars and tribal community members. On collaborative and decolonizing possibilities, see Jordan E. Kerber, ed., Cross-Cultural Collaboration: Native Peoples and Archaeology in the Northeastern United States (Lincoln, Neb., 2006); Sonya Atalay, Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities (Berkeley, Calif., 2012), especially the concept of “braiding knowledge”; Margaret M. Bruchac, “Lost and Found: NAGPRA, Scattered Relics, and Restorative Methodologies,” Museum Anthropology 33:2 (2010): 137-156; Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2012); Susan Sleeper-Smith, ed., Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives (Lincoln, Neb., 2009).

This article originally appeared in issue 17.2 (Winter, 2017).

Christine DeLucia is an assistant professor of history at Mount Holyoke College, and a PhD in American Studies from Yale University. Her first book, The Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast (forthcoming from Yale University Press in the Henry Roe Cloud Series on American Indians and Modernity, 2017), examines Native American and colonial understandings of place and memory in the wake of seventeenth-century conflicts.