Recounting a scene from her childhood in Bermuda, Mary Prince describes the following,

I recollect the day well. Mrs Pruden came to me and said, ‘Mary, you will have to go home directly; your master is going to be married, and he means to sell you and two of your sisters to raise money for the wedding.’ Hearing this I burst out a crying, – though I was then far from being sensible of the full weight of my misfortune, or of the misery that waited for me.

This moment reads as one of Prince’s earliest memories of living through a vast system of exchange. “Though I was then far from being sensible” of it, she claims, her following response, to “burst out a crying,” suggests that even as a child, she knew of the “weight” around her. Indeed by the time she narrated her story to amanuensis Susana Strickland and editor Thomas Pringle from London’s Anti-Slavery Society, she consistently framed this “weight” in terms of resources and “money.”

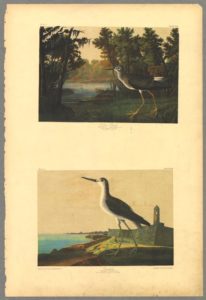

The first narrative published in Britain portraying a Black woman’s experiences of enslavement, The History of Mary Prince (1831) is also severely mediated, making the question of Prince’s specific word choices impossible to settle. (Figure 1) Within the narrow rhetoric of antislavery politics that shape Prince’s narrative, however, steady articulation of money markets, repeated reference to financial transactions, and descriptions of resource accrual stand out in a declared autobiography, a distinctly literary production. Indeed, in this early scene from the text, Prince repeats financially inflected terms from “recollect” to “raise money” to “misfortune.” By signaling changes in location from where she is when Mrs. Pruden arrives, to her subsequently “go[ing] home,” to the implied setting of the upcoming “wedding” event, she takes stock of the geography of capital. By keeping “the wedding” ever imminent and foreshadowing all “that waited for me,” she calls attention to time, implying the role that the future plays in determining value. For Prince, such accounting contains at once economic and narrative valences. As this dynamic unfolds over the course of The History, money and resources become sites through which she exerts authorial agency when transcription and revision, and the larger politics of literacy, confine and control her voice. In this way, Prince speaks back to the history of Atlantic world accounting that has subjected her to the ledger or written her off completely. The following traces a genealogy that moves from the middle passage to the passage of trade laws, to dwell in the entangled histories of financial economics and literary narrative, and contextualize Prince’s distinct mode of recounting.

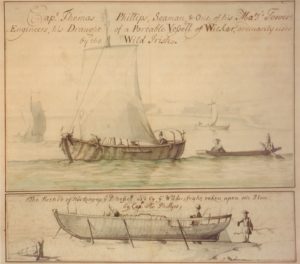

In this history of accounting, before Mary Prince, there was Thomas Phillips, commander of the slave ship Hannibal. Once “entered into the[. . .] service,” and “accepte[d]” “upon [the] account” of Sirs Jeffery and John Jefferys, Phillips begins at once his work in the Atlantic slave trade and in his own journal of accounts. On the clock every moment from 1693 to 1694, he enumerates, entry after entry, all that his work involves: his time setting off, the patterns in wind and ocean currents, locational coordinates as soon as they change, and carefully traced profile sketches of upcoming landmasses. As the voyage of the Hannibal continues, however, Phillips’s accounting increasingly stalls and swerves. From the Leeward Islands, he remarks,

From noon yesterday we stood off shore, lying up W. by S. and W. S. W. till four; then in again lying S. S. by S. till six; when reflecting on the time it might cost me to endeavor to get into cape Lopus, (where I design’d to wood and water) by reason of the uncertainty of the winds, and the current setting us to leeward; which together with my negroes dying very fast, and the want of some provisions I was in, made me resolve to stand over for the island of St. Thomas, about 40 leagues distant . . . Accordingly . . . We lay up west, W. by S. and W. S. W. at night, till six this morning; when the wind scanted to S. W. by S. and S. W. so that we could lie but W. by N. and W. N. W. till noon this day.

By the time Phillips explicitly records the slave trade work of the Hannibal, his sailors have started fighting over food and “[his] negroes [are] dying very fast.” Perhaps taking advantage of a surge of wind, or at least staging one, Phillips surrounds the Hannibal’s enslaved peoples with delirious navigational readings, in essence throwing the winds all around and dissembling the “negroes” at the center of this account. As the lethal conditions of the hold palpably manifest and the harsh scrambles of slave markets insistently approach, Phillips’s account continues to avoid the present scene, and increasingly crumbles into a nautical shorthand until, in the journal’s final pages, he compresses the last four months of the voyage into six tight columns that range from date to distance covered, and states brusquely, “This Table is so plain, that it needs no illustrating.” (Figure 2)

Even before slave ships left Europe for trade on the west coast of Africa, however, the prophetic foresight of insurance and its undergirding logic of credit guaranteed that whatever happened, the bottom line would prevail. Since parties agreed to the payoff of the voyage in their contract, Ian Baucom explains, “exchange . . . does not [ultimately] create value,” but “retrospectively confirms it, offer[ing] belated evidence to what already exists.” According to Baucom, this practice of underwriting, or the accounting of commodities trade, stands as an early installation of the workings of “allegorization” that Walter Benjamin would later interpret. Through each successive exchange, Baucom infers, subjects increasingly “signify not themselves but some superordinate ‘value.’” Indeed, this accrual of value through repeated exchange spurs a process of abstraction that ultimately presents the subject not as itself but as a symbol of itself, its social as much as financial currency on track to grow and grow. Markets thus perpetually allegorize the subject, degrading its reality to the point of outright dissolution. Steadily increasing value this way relies on steadily increasing absence; when the subject of exchange disappears entirely from transactions, commodities trading, of material commodities, meets finance capital. “As if by a sublime trick of the imagination,” Baucom explains, commerce starts to “breed money from money,” as though allegory upon allegory, and trade becomes “a constant oscillation between monetary and commodity capital,” between allegory and reality, each driving as much as interfering with the deemed value of the other. If for Phillips accounting appears in his dramatic efforts to conjure the wind and blow away the scenes of slavery, then, with the rise of eighteenth-century finance capital, the scenes are almost pushed away completely, through an elaborate scheme of accounting’s trajectory from the superordinate towards an unhinged ideal and the promise of the bottom line.

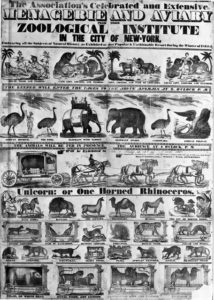

Though the draw of the superordinate gradually displaces the material presence of slavery, the elaborate fantasies of finance capital can still be said to manifest materially in the form of natural history, a practice and a genre both organized around gathering, arranging, and exchanging the many, many “curiosities” of apparently exotic ecologies. If accounting so far appears as entries in the trader’s ledger and as notes in the pockets of metropolitan investors, then the innumerable sketches of equinoctial trees, the poetic blazons on migrating birds, and the lengthy observational lists, together index empire’s attempt to account for the entire Earth. Indeed, “reality was fantasized here as well,” writes Édouard Glissant on such enthusiastic efforts, by which, he goes on, “conventional landscape [is] pushed to extremes . . . particularly in the islands of the Caribbean.” Thus in natural history projects, we see a “propensity to blot out . . . the shudders of life, that is, the turbulent realities of the Plantation, beneath the conventional splendor of scenery.” Alongside Glissant, Jamaica Kincaid calls attention to this distinct form “blot[ting] out” or overwriting, explaining of her native island, “Antigua is beautiful. Antigua is too beautiful. Sometimes the beauty of it seems unreal. Sometimes the beauty of it seems as if it were stage sets for a play.” (Figure 3) By accounting for everything, by “collecting the world,” and insisting on a luminous and knowing beauty seen only in surrounding nature, imperial and colonial agents of natural history gradually displace “the turbulent realities” surrounding them. Writing over this reality, in a purported attempt to account for everything, natural history becomes a cluttered “stage” that covers over the coerced labor of those who make such excursions and extractions possible. The genre, in fact, comes to crowd out the world as it really is. (Figure 4)

A series of late eighteenth-century British laws increasingly revealed the central presence and politics of slavery in early modern exchange and life. The first Slave Trade Act passed by the British Parliament in 1788 set strict regulations on the ratio between square meters or ship tonnage, and the number of African peoples who investors, captains, and sailors enslaved and transported to the Americas. This moment is often framed as the result of increasing antislavery and abolitionist movements across the Atlantic world, and as a distinct event representing, if not advancing, Enlightenment ideals. “But [accounting] is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous,” to quote Michel-Rolph Trouillot on the insidious reach of power. Anti-slavery advocates at the time of course worried that instead of abolishing the slave trade and slavery, the Slave Trade Act would only signal that endlessly changing regulations were sufficient. We might also read the Act as an expansion and mutation of the same financial accounting it purportedly strove to undo. If not in intent, then in consequence, in promising to reduce mortality rates among enslaved peoples, the Slave Trade Act ultimately made it possible to reduce the margin of error insurers calculated, to stabilize valuation, and to make the industry’s accounting more predictable and the industry more profitable.

From journaling to underwriting to overwriting to legal declarations, the literary accounting of the New World has routinely concealed the economic accounting of slavery. For Mary Prince, the occasion to recount sees her reframe such subjection to trade as a means for authorial voice. When she was first “put up to sale,” Prince explains, “[t]he bidding commenced at a few pounds, and gradually rose to fifty-seven, when I was knocked down to the highest bidder; and the people who stood by said that I had fetched a great sum for so young a slave.” Repeating “I” and “I,” Prince emphasizes her person within the “few pounds,” the “fifty-seven,” the final “great sum.” When she is enslaved on hire at “Cedar Hills” in northern Bermuda, she states, “I earned two dollars and a quarter a week, which is twenty pence a day.” From keeping track of changing bids to breaking down her wages, Prince increasingly shows a practiced study of money and numbers. (Figure 6)

With literary literacy routinely denied her, from Bermuda to London, Prince expresses a decided numeracy that reclaims accounting as her narrative form. As she draws out her “I,” she also shifts from the passive voice, “I was knocked down,” to the active “I had fetched,” and in doing, pushes presence into dynamic being—she made money move that day. When she calculates her wages, she is clear about her agency—“I earned”—and signals her authority beyond a single day’s pay; her impact lasts weeks, months, lifetimes. Prince extends her financial literacy into a practice of reappraisal when she describes her labors on Turks Islands and details the relentless periods she spent raking for salt, diving for rocks, “cut[ting] up mangoes to burn lime with,” and “break[ing] up coral out of the sea.” Nodding towards the accounting principles of natural history that list ecological phenomena one after another and state their myriad potentials as commercial and luxury resources, Prince reframes the “splendor” and “scenery” that might otherwise result by insisting, with each gesture towards fruit or mention of sea creatures, on the brutal conditions and forced labor that determined these collections. Finally, Prince’s numeracy continues as a critique of larger economic spheres when she describes how a former enslaver, Mr. D—, later negotiates with Mr. and Mrs. Wood. Prince relays, “I was purchased by Mr Wood for 300 dollars, (£100 Bermuda currency).” Though she shifts into the passive voice, “I was purchased,” her conversion of “300 dollars” into “(£100 Bermuda currency)” suggests as much her ease with managing accounting across international borders, as her keen sense of her impact on global markets and world history.

Can we sit easily, though, with Prince’s recounting and numeracy as an endpoint in this genealogy, when we know such accounting still signals an entanglement with violent systems that emerged and continue at her expense? “Are the merchant’s words the bridge to the dead or [are they] the scriptural tombs in which the [dead] await us?” Saidiya Hartman asks. “It is not possible to undo the violence that inaugurates the sparse record of a girl’s life . . . or [to] translate the commodity’s speech,” Hartman continues. Prince’s numeracy might be, then, a “stor[y] one tells in dark times,” that is, the accounting of and for the “meantime” between “a narrative of defeat” and “an alternative future.” The project of reparations, Prince makes clear, is as much about how to spend cash as what stories to tell.

Further Reading

Ian Baucom, Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005).

James Delbourgo, Collecting the World: Hans Sloane and the Origins of the British Museum (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2017).

Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation Trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2010).

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (June 2008): 1-14.

Christopher P. Iannini, Fatal Revolutions: Natural History, West Indian Slavery, and the Routes of American Literature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2012).

Jamaica Kincaid, A Small Place (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1988).

Kris Manjapra, “Necrospeculation: Postemancipation Finance and Black Redress,” Social Text 37, no. 2 (2019), 29-65.

Jennifer Morgan, Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2006).

Thomas Phillips, “A Journal of a Voyage made in the Hannibal of London, Ann. 1693, 1694, from England to Cape Monseradoe, in Africa . . . ” A Collection of Voyages and Travels, some Now first Printed from Original Manuscripts, others Now first Published in English, 3rd ed., vol. 1 (London: 1744-46).

Mary Prince, The History of Mary Prince (London: Penguin Books, 2000).

Caitlin Rosenthal, Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015).

This article originally appeared in September 2021.

Katrina Dzyak is a Ph.D. Candidate in English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University.