Benedict Arnold’s House: The Making and Unmaking of an American

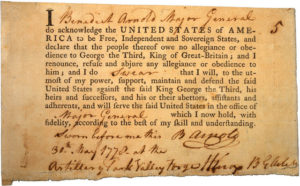

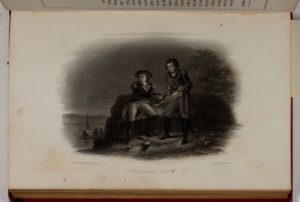

Benedict Arnold (1740/41-1801) was a member of the Revolutionary generation whose life and legacy took a different turn from the men with whom he was most closely associated. (Figure 1) Before signing the Oath of Allegiance to the United States of America in 1778 at Valley Forge (Figure 2), Arnold had lived his thirty-seven years as a subject to the British Crown. In a few short years full of activity, Arnold became George Washington’s most capable field general, someone Washington came to trust and depend on. But in 1780, feeling slighted both financially and professionally, Arnold attempted to give over both Washington and West Point to the British in exchange for money and a higher rank in King George III’s army. The plan, which would have divided the colonies in two, was discovered at the eleventh hour when evidence incriminating Arnold was found in his British accomplice John André’s boot. Arnold’s oath and material world evaporated overnight and his name became a synonym for “traitor.” Arnold’s image and name are regularly revived in popular culture and in our image-steeped digital media environment as shorthand for treasonous behavior. Even if they don’t know much about the Revolution, many Americans know that to be a “Benedict Arnold” is not a good thing.

Historians have examined the many aspects, both positive and negative, of Arnold’s impact on the course of events leading to the establishment of the United States. Yet the largely unanalyzed material culture of his existence—the objects he acquired and the buildings in which he and his family resided—can offer us much more about the contours of his life as he fashioned it, and how others crafted his historical memory. Arnold’s unceasing efforts to elevate himself in society through marriage and professional work can be viewed through the lens of the houses he bought or built throughout his life. This essay looks at the cultural landscape of one of his homes, the New Haven, Connecticut, house he built and resided in from 1769 until wartime. Through an analysis of the choices Arnold made in location, size, and architectural style, I identify how Arnold began to construct his identity not only as a member of the urban merchant class, but also as a gentleman. The building of the home reads as material evidence of his desire to establish his identity and place in society, but equally the abuse and destruction of Arnold’s house is a parallel to the untimely end of a life and career he worked hard to obtain.

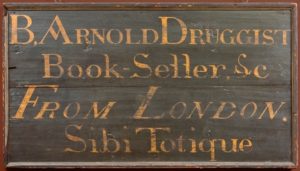

The first house Arnold built for himself and his family (although not the last) was a material symbol of the life the merchant aspired to. He chose New Haven, already a center for maritime trade and education by the mid-eighteenth century, as the locale from which to design this life. Arnold came to New Haven after having served as an apprentice apothecary in Norwich, Connecticut, the town of his birth, fifty-six miles east along the Atlantic coast. His father died from alcoholism, forcing Arnold to learn a trade rather than attend Yale College, as did many other male Connecticut residents of his age and class. Arnold’s shop in New Haven grew prosperous thanks to his vision of Sibi Totique, meaning “for himself and for everyone” in Latin, which he had painted on his shop sign. (Figure 3) Arnold himself sailed on many trading voyages to the West Indies, becoming a proficient sea captain and gaining skills he would later transform into an ability to lead armies on both land and water during the Revolutionary War.

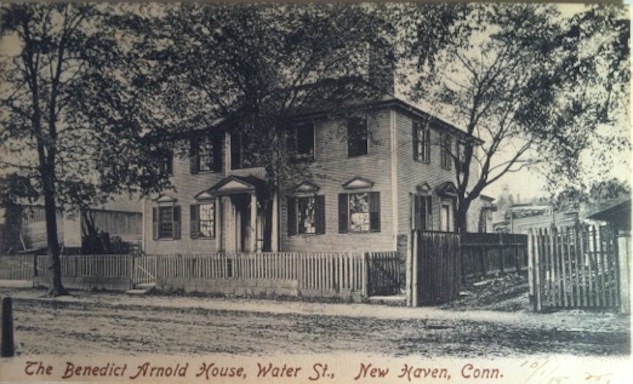

Little documentation exists for the construction of the New Haven house and Arnold did not write about it, except to refer to his life during these years as one of “domestic ease and happiness.” In a view of the house from its rear façade, looking out over Long Wharf, the city’s earliest and most important wharf, it becomes clear that Arnold shaped himself materially in a way that his father could never manage. (Figure 4) Before Arnold left to join the Continentals in Lexington and Concord in 1775, he returned to Norwich, where he was born, and sold his father’s house, forcing his unmarried sister to live with his family in New Haven.

Arnold’s attempt to craft a genteel life for himself is demonstrated when looking at the details of the house itself, as first seen in a photographic postcard from the last quarter of the nineteenth century. (Figure 5) Built before the American Revolution and part of the British Atlantic World, it was a large wood-frame eighteenth-century house with a hipped roof, fanlight over the doorway, and central Palladian window. There were unusual Greek Revival decorative details over the windows and the flat area of the roof likely had an addition called a monitor. Some architectural historians question the mix of details and suggest it may have been “Federalized” in the 1790s, perhaps by Noah Webster while the author of the first American dictionary wrote several chapters of his massive work in the front rooms.

Arnold’s house was not the largest, nor the most expensive in New Haven. But its architectural style and geographic location suggest that Arnold, like many ambitious men across the Atlantic World, in the words of Stephen Hague, “employed their houses in precise ways across a range of settings to project power and define status.” In other words, building a gentlemen’s house and marrying a woman from a solid New Haven family provided Arnold with the respectability that he did not have in Norwich. As a young man, Arnold would often bring his inebriated father home from the tavern; everyone in town knew him as the son of a drunk. In New Haven, Arnold became a prosperous—if argumentative—town leader, elected to the high-status Freemasons and accepted as a member of the oldest church which dated to the town’s 1638 founding. Although neither a floor plan nor interior images of the house survive, tantalizing hints remain of what the interior may have looked like during Arnold’s life. A few architectural elements such as a lock and key, a doorknob, and a mantel exist at the New Haven Museum, the last of which was reused in an office space when the current Colonial Revival structure was built in 1930.

The story of Benedict Arnold and his houses is more complicated than his childhood home in Norwich and his “starter” home in New Haven. During his rise in fame and an early brush with infamy—he was court martialed for misusing government property while serving as military governor of Philadelphia—Arnold bought a larger house in that prosperous center of American colonial life and society. Philadelphia was also the home of his second wife, Margaret “Peggy” Shippen, the daughter of a household with Loyalist sympathies. The house, called Mount Pleasant, is much larger in scale and more ornate in material and decoration than the New Haven house, and although of the same Neoclassical Georgian flavor, it was built in stone instead of timber frame, and was positioned on a cliff overlooking the Schuylkill River. (Figure 6) For Arnold, the Philadelphia house had a pedigree he also did not have access to in New Haven. The architect-builder was Thomas Nevell, an apprentice to Edmund Woolley who had designed Independence Hall. Today the house is administered by the Philadelphia Museum of Art as a decorative arts museum in partnership with Fairmont Park, an arrangement which John Adams, a visitor in 1775, would have agreed with. Adams had called Mount Pleasant “the most elegant seat in Pennsylvania.” And for a very short time, the house was Arnold’s.

In Philadelphia, Arnold might have become an older, more successful, and perhaps wiser member of elite society. He had the beautiful Peggy Shippen at his side, he was the father to eight children (seven of whom were boys), and he had purchased Mount Pleasant, recognized as a prize by others. But none of this came to pass. The Arnolds, in fact, owned the house for only a year, and Arnold never lived there himself. Wounded twice on the battlefield, he was dissatisfied with his administrative role in Philadelphia. Angered by his reprimand from George Washington, stressed under the weight of his debts and now in conversation with John André on behalf of the enemy, Arnold petitioned Washington for his re-appointment as Commander of West Point, and thus began to unmake his carefully crafted Anglo-American life.

After Arnold’s defection in 1780 and later his death in London in 1801—barely noted on either side of the Atlantic—the New Haven house remained somewhat of a local landmark. In 1890, towards the end of the house’s existence, the New Haven Register described “some grey-haired citizens who remember it when it was one of the show places of the town . . . with an orchard, and grounds laid out in handsome terraces.” Perhaps the house appeared as it does in a romanticized nineteenth-century painting that is in the collection of the Second Company, Governor’s Foot Guard (which Arnold once captained). It depicts him standing in contrapposto in front of the house, gingerly keeping weight off his right leg, wounded for the second time at Saratoga. The same journalist noted that the house had a “highly ornamented English style wallpaper” which could be seen under layers of more paper. Not surprisingly, during the era of antiquarianism and the Colonial Revival, the Arnold house became a site for relic hunters.

The final straw was the abuse of the house by the W. A. Beckley Lumber Company, which had the house’s Classical front doorway removed, with the open space of the central hallway serving as a driveway of sorts to the rear. One newspaper reported that these changes signaled the “triumph of the material spirit of the time over sentiment.” (Figure 7) The house was gutted to create space for stacks of lumber. One journalist noted that it was a shame the house had been altered so painfully, and then eventually torn down about 1910 because the house was a “relic of New Haven’s past.” Further, with an unusually balanced view of Arnold, the same journalist reported that the house could be “handed down to posterity as a memorial of one whose name is to be forever identified with the struggles of this nation.” But this view was shared by few, in either New Haven or the rest of the country. Arnold had been branded a traitor, a label that sticks to this day. Any efforts he had expended in the cause of liberty erased, his name and personhood becoming a symbol, and the contours and material culture of his personal life relatively unknown. (Figure 8)

A century later, this area of New Haven is so completely changed by redevelopment that it is hard to imagine Arnold’s house in situ at all. The foundations and brick-made basement are possibly located today under an asphalt parking lot. There is no historical marker and in a recent biography of Arnold, a photograph of a different house altogether is erroneously presented as the New Haven house. In terms of historic preservation in the United States, which began life around the houses of the Revolutionary generation, if Arnold’s house had survived, the historic maritime character of Water Street and the Fifth Ward might have survived, too. Although Arnold’s New Haven house was not destined to “take its place among the historic mansions of New England” as the New York Daily Tribune suggested, the architectural, social, and biographical history of Arnold’s New Haven house survives in fragmented form. Knowledge of the house is contributing evidence to a story that continues to fascinate, a real story in which both a man and his house were made and unmade.

Further Reading

Under the leadership of historic site staff and scholars, the interpretation and presentation of Loyalist houses in the United States and Canada continues to evolve. Because he was a traitor, Benedict Arnold’s houses have received far less attention than those of his Patriot or Loyalist contemporaries. For an understanding of the Atlantic world context in which Arnold built his first house, see Stephen Hague, The Gentleman’s House in the British Atlantic World, 1680-1780 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). Although there is no narrative publication for domestic architecture and social history in New Haven beyond Elizabeth Mills Brown’s New Haven, A Guide to Architecture and Design (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1976), the history of Arnold’s Philadelphia house can be situated in Mark Reinberger and Elizabeth McLean, The Philadelphia Country House, Architecture and Landscape in Colonial America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015). Biographies of Arnold have appeared since the early nineteenth century. The most recent is Joyce Lee Malcolm’s The Tragedy of Benedict Arnold, An American Life (New York: Pegasus Books, 2018). For a popular account of the relationship between George Washington and Benedict Arnold, and their shared personal and professional aspirations, see Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (New York: Viking, 2016). Finally, it should be noted that many publications exist to teach Americans about the Revolutionary generation through their historic houses such as Hugh Howard, Houses of the Founding Fathers, The Men Who Made America and the Way They Lived (New York: Artisan, 2012). By not including houses which no longer stand, nor the houses of those deemed unworthy of preservation and interpretation, the information given out is partial at best, contributing to the false view that the American Revolution was a straight-line trajectory, instead of the continuously evolving, bloody transition where real people made difficult decisions affecting their own lives and the society we live in today.

This article originally appeared in October 2021.

Laura A. Macaluso researches and writes about material culture, monuments, and museums. In 2021 her essay “Spiel mit mir!” (Play with Me!) will appear in the volume Was denkt das denkmal? (What does the monument think?) edited by Tanja Schult and Julia Lange (Böhlau Verlag). She is finishing work on the book A History Lover’s Guide to Alexandria and South Fairfax County and serves as a History Interpreter at George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Laura has a Ph.D. in the Humanities / Cultural & Historic Preservation from Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island. See more of her work at www.lauramacaluso.com or on Twitter at @monumentculture.