This is not the first time that Commonplace confronted questions about our use of social media. A few years ago, we wrestled with how to handle the surge of Covid misinformation, troll farm posting about the Black Lives Matter protests, and a burgeoning Cambridge Analytica scandal related to Facebook. We followed the lead of one of our sponsors, the Omohundro Institute, as they reassessed their use of social media. The OI statement released at the time explained that “information integrity is at the heart of the Omohundro Institute’s mission. Sharing scholarship and the scholarly process with the public is so important to us because we know that understanding how we get to high quality scholarship is key to that integrity.” We wholeheartedly agreed and suspended new Facebook posting for Commonplace in June 2020.

With the recent ownership change at Twitter, we have been confronted by similar questions and have been discussing if another change is required. Whether it is the decision to re-platform white nationalist accounts or broadcast homophobic and antisemitic posts from the highest levels, the site has very quickly come to feel like a different social media space. Also contributing to my sense of unease is the chaos that the new ownership has manufactured by rapidly changing rules and policies. In just the time that I have been working on this piece, several high-profile journalists have had their Twitter accounts suspended for questionable reasons, which led to another call for people to leave the site and move to alternatives like Mastodon or Post.

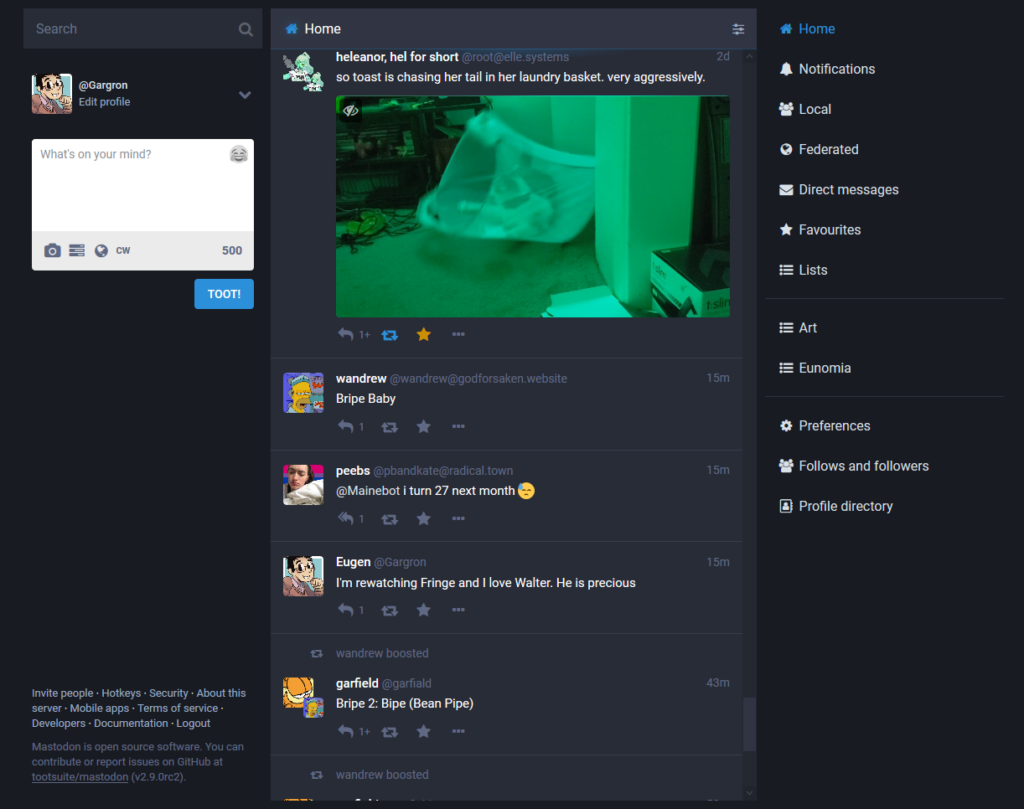

The size of Twitter and its reach means that there is not necessarily an easy replacement right now for most people and organizations (if there was, I think a much greater number of people would have already left). The leading options right now seem to be Post, which is still in beta form and currently places prospective users on a waitlist, and Mastodon, a collection of independently run, federated social media servers called “instances.” For some users these sites are not as easy to navigate as Twitter and they may be unwilling to take the time to learn. Another question that users have been asking is if the audience on these sites will be as diverse as Twitter. Just a few weeks into the movement of people from Twitter to Mastodon, critics have questioned whether the site will host similar numbers of people of color and how those accounts will be treated. One recent and reassuring piece of news for history-minded social media users interested in Mastodon is the launch of an instance called historians.social by Karin Wulf, Joseph Adelman, and Liz Covart, current and former OI colleagues who clearly spell out their moderation philosophy in their code of conduct.