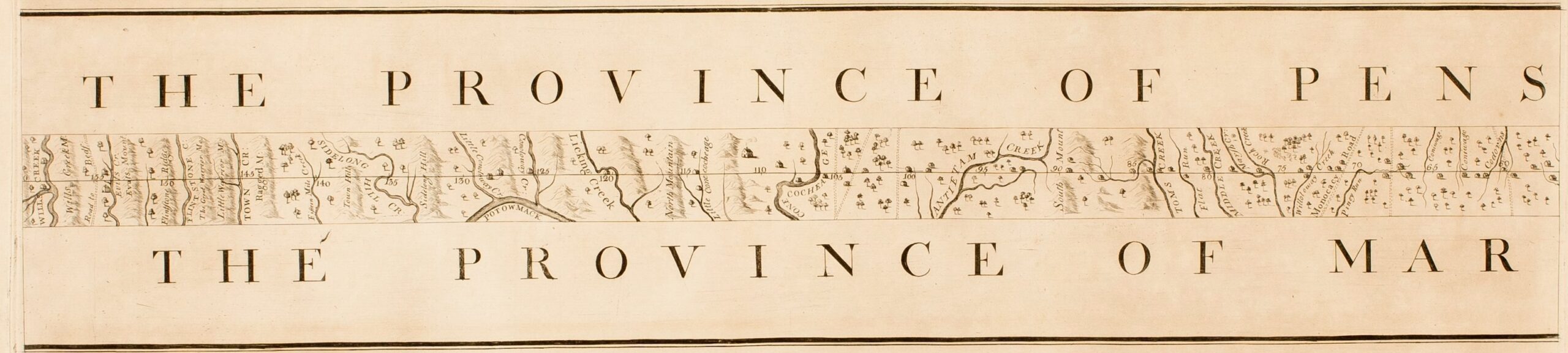

During the thirty-two years I taught college-level American literature I homed in on two academic specialties: seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American women writers and the literary form called the captivity narrative. Mary Rowlandson’s (c. 1637-1711) famous account of her three-month captivity among the Nipmuck, Narragansett, and Wampanoag Indians combines my two research interests, and I published widely on it (fig. 1). As a good Puritan—a minister’s wife, no less—Rowlandson used biblical rhetoric and precedent to channel her terror at being taken from her home in Lancaster, Massachusetts, and forced into what she called “the vast and desolate Wilderness.” She composed her narrative shortly after she had safely returned to the fold, and in its exquisite final paragraph, she tried to reach the spiritually assuaging but psychologically wrenching conclusion that God loved her so much He had sent a horrific trial to test her. Yet all was not well. Spiritual security eluded her and she continued to suffer from nightmares and insomnia.

When I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2014, I too was abruptly removed from a familiar, comfortable life (“in health, and wealth, wanting nothing” as Rowlandson says) and dumped into a desolate thicket. Surprisingly, it seemed to me that the conditions of cancer and captivity shared physical, emotional, and spiritual correspondences. Like Rowlandson, I wondered whether my faith would sustain me and whether my affliction was truly god-sent. I’m a liberal Episcopalian so my theological frame of reference is, of course, radically different from that of a late seventeenth-century Puritan woman. Yet Rowlandson’s reflections on the redemptive role of affliction in her conclusion reached me viscerally as a sister-in-suffering. And her repeated attempts to convey her pain and guilt at the end of her account through the nouns “affliction” (which she used six times), “trials,” “difficulties,” and “troubles” and the verbs “chasteneth/chasten,” “scourgeth/scourge,” “afflicted,” and “troubled” particularly moved me.

In my many re-readings of Rowlandson’s narrative over the years, the following sentence in her last paragraph had always rankled, “And I hope I can say in some measure, as David did, It is good for me that I have been afflicted” (fig. 2). After my cancer diagnosis, her words assumed a profoundly personal significance. They haunted me during my treatments until, one day, I burst out, “No! It is not good for me that I have been afflicted and I am not a better person for it.” I tend to see Rowlandson’s finale as a capitulation to Puritan orthodoxy despite narrative tensions elsewhere that hint at her rebelliousness. But some other scholars assert that her words do not affirm providentialism as much as they question or even reject it.

In the twenty-first century, a belief in the positive role of suffering is not confined to people of faith. There’s a secular version too. We’ve all heard family or friends say that a trauma, especially a serious illness, changed their life for the better. Not immediately, perhaps, but as they reflect on their experience, they discern a clearer sense of priorities that rationalizes what happened to them and helps them to accept it. It’s as if the kaleidoscope of life shifts into new patterns and colors. Several people I know who also went through cancer treatments came right out and said, “I am a better person now.” They apparently assumed that I would agree with them about cancer’s role in self-improvement.

Some went even further and called cancer a gift, which I found truly offensive. On this subject I concur with Lisa Bonchek Adams, who blogged and tweeted about her struggle with metastatic breast cancer but who eventually succumbed to the disease in 2015. A New York Times Magazine article about her explains, “She detested the notion that cancer was a gift. (Really, she asked, would you give it to somebody?).” Barbara Ehrenreich also debunks the prevailing cultural imperative that cancer be uplifting in her essay “Smile! You’ve Got Cancer.” She is particularly outraged that patients who (understandably) exhibit anger and negativity are dismissed outright or accused of being complicit in their own decline as if they are committing a social sin. The cruel disconnect implied in Ehrenreich’s title says it all. Is secular providentialism or spiritual providentialism more disquieting? The latter, I suppose, because it figures a punitive and perverse God—the very God, I believe, that Rowlandson tried so hard to come to terms with.

Apart from my personal reaction to Rowlandson’s narrative, the scholar in me was curious to explore two questions about Puritan culture that I had not previously considered: how did deterministic Puritans interpret serious illnesses like cancer, and did they see an afflictive connection between cancer (illness) and captivity? On the surface, such a link seemed unlikely, but when I probed further I found plenty of supporting evidence.

While the nuts and bolts of Puritan belief in the colonies were hotly debated toward the end of the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth, the various factions subscribed to certain basic tenets. Puritans thought that their place in heaven or hell was predetermined and that God was omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent. Since God was hyper vigilant, it behooved them to be, too—as far as humanly possible. So they became inveterate interpreters as they tried to assign meaning to events. The clergy, of course, possessed the most experience and authority to read the signs of both major occurrences (“special providences”) and minor ones (“common providences”), including disease and captivity. Because Puritans needed to shun pride, they could not bask in good fortune or conclude for very long that God favored them. Hence, for much of Rowlandson’s life, she felt “jealous” of those whom God tried with “sickness, weakness, poverty, losses, crosses, and cares of the World.” Comfort caused complacency; suffering fostered spiritual growth. Yet underlying the belief that God tried those He loved was another aspect of Puritan theology: that the stricken were being punished for their own or for communal errors or both. Indeed, illness and incarceration constituted such acute, immediate afflictions they could easily be yoked to individual as well as public wrongdoing.

Puritans often took their interpretive cues from prominent ministers like the physician-poet Michael Wigglesworth. Best known for his epic poem The Day of Doom (1662), Wigglesworth also published a variety of popular verses including a series of poems collectively titled “Meat out of the Eater” (1670). The latter work tackled the thorny nature of human affliction and divine reward through the segment “Riddles Unriddled, or Christian Paradoxes,” which is further subdivided into subsections consisting of several meditations or songs. The titles of these subsections verbally dramatize Puritanism’s theological contradictions: “Light in Darkness,” “Sick Men’s Health,” “Strength in Weakness,” “Poor Men’s Wealth,” “In Confinement Liberty,” “In Solitude Good Company,” “Joy in Sorrow,” “Life in Deaths,”[sic] and “Heavenly Crowns for Thorny Wreaths.” The most tangible trials on this list are illness and imprisonment, leading Wigglesworth biographer Richard Crowder to say that the preacher’s “two chief instances of affliction were sickness and incarceration.” Or, if I can use my own synecdochic terms to signify all illnesses and all confinements, cancer and captivity. Wigglesworth believed that his own prolonged ill health and family tragedies provided incontrovertible evidence of the relationship between physical entrapment and spiritual growth, and he drew on his experiences to sway others.

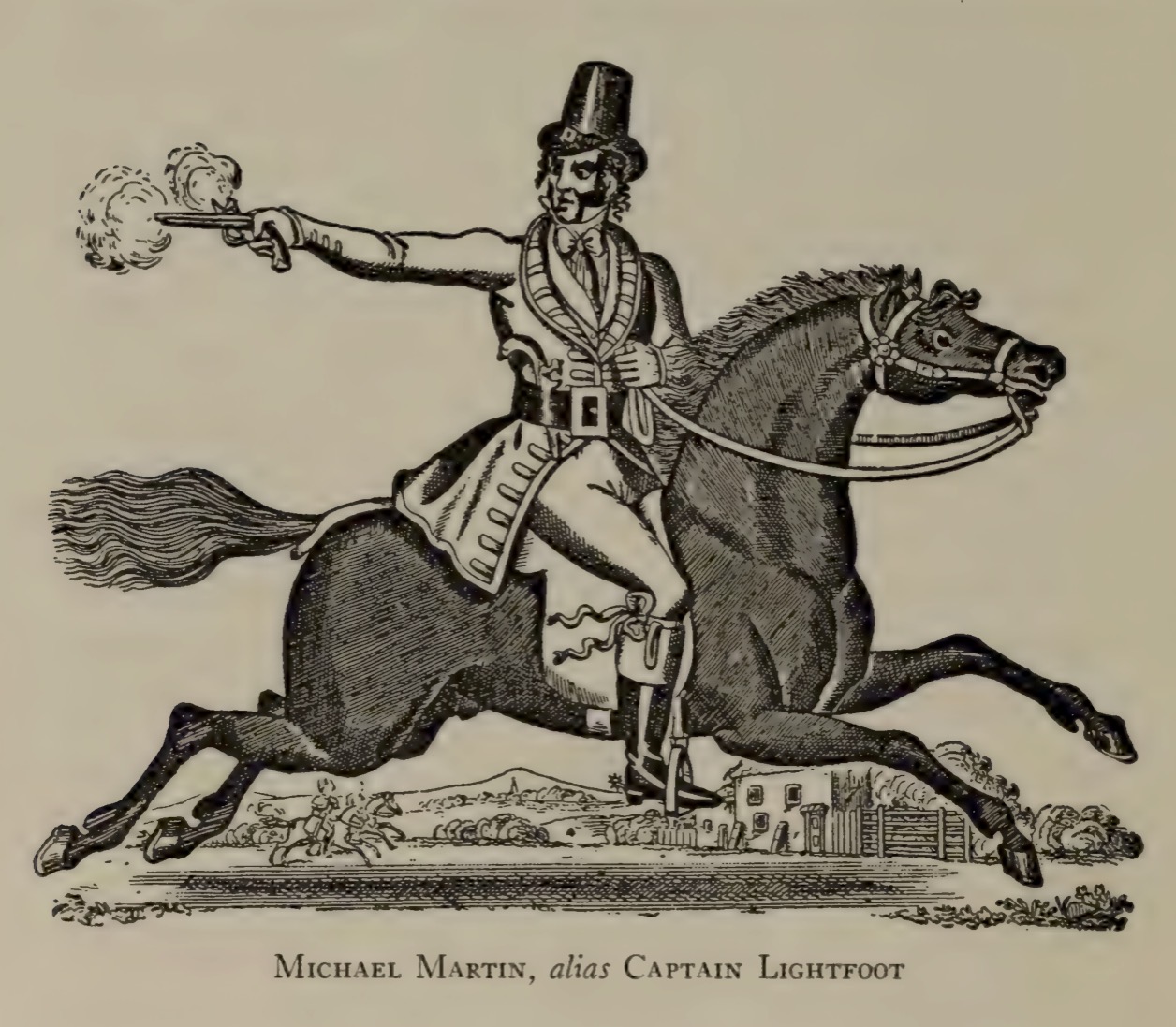

For example, in “Meditation 1” of “Sick Men’s Health,” Wigglesworth states that “Of all Afflictions that / The outward man oppress, / None are more grievous to endure / Than Pains and Sicknesses” and he cites the trials of Job, Hezekiah, and Lazarus. And in verse five of “Song 1” in the subsection “In Confinement Liberty,” he describes the ironically liberating effects of bondage: “God bindeth some in Chains, / And in Afflictions Cords, / And by these Bands, unto their Souls / More Libertie affords. / Who would not be in thrall, / Soul-Liberty to gain, / Rather than Sins and Satan’s thrall, / And Captive to remain?” Wigglesworth was not the only commentator who thought that the most excruciating trials lay in sickness and bondage. For early Americans constantly faced daunting dangers from disease, death, and captivity, especially those like Wigglesworth who lived in vulnerable outlying villages.

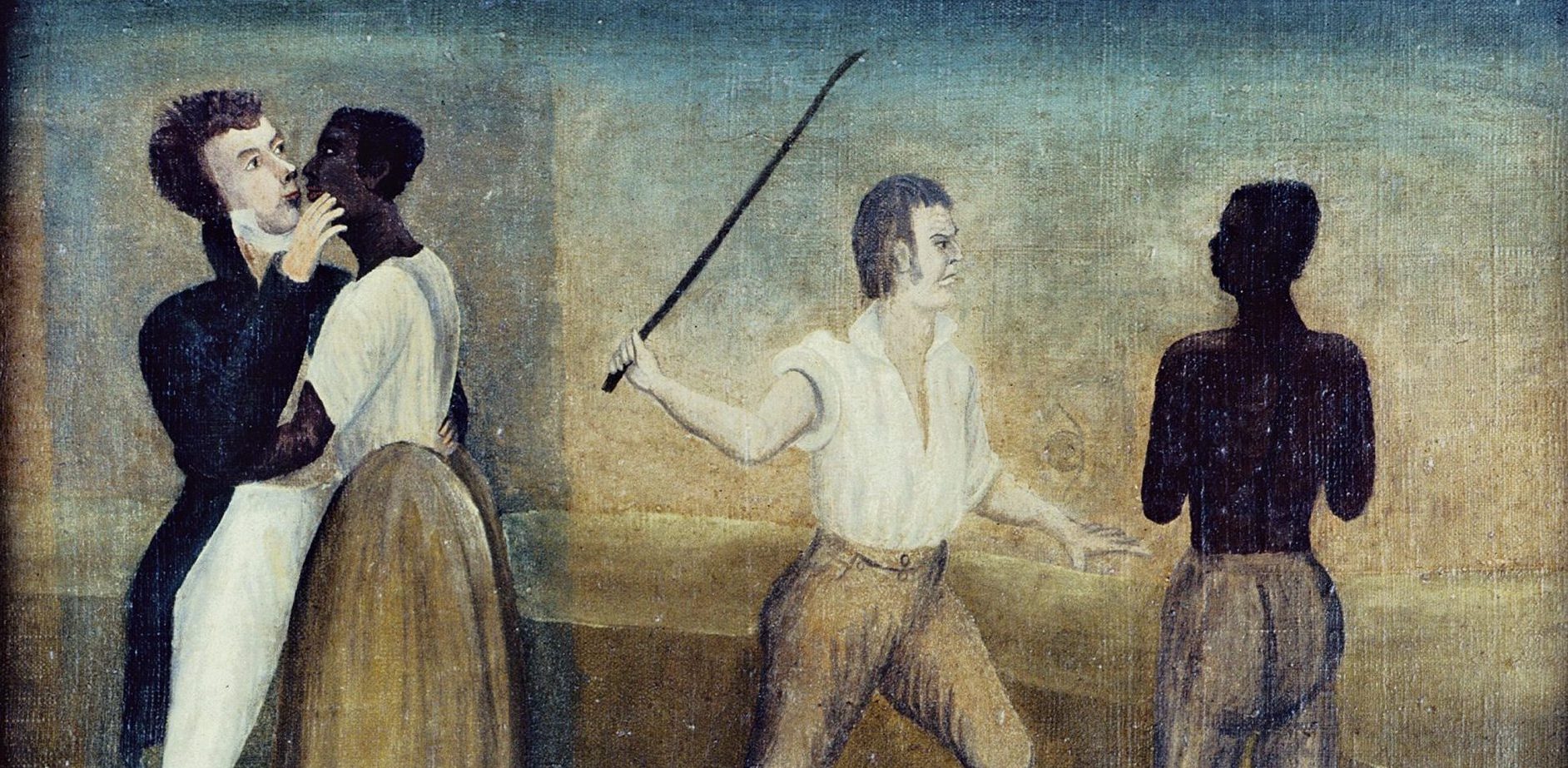

While illness or captivity alone was bad enough, affliction was reinforced when individuals experienced both conditions at the same time. And a number of testimonials attest to this double misery. Rowlandson’s narrative, for example, contains information on the wounds she sustained during the initial raid on her home as well as her mental fragility afterward. Indeed, years ago, I wrote an article suggesting that she exhibited standard symptoms of what’s now called PTSD. Many captivity narratives also included information on the captive’s ill health, such as physical and psychological problems as a result of childbirth plus injuries sustained during or after an attack. In addition, there’s a whole sub-genre of early American accounts about quarantine, yet another form of confinement, necessitated by contagious diseases like smallpox and yellow fever.

But whether Puritan theology really supported the claim that illness and captivity were the two worst afflictions that could befall human beings is a different matter. Wigglesworth, for example, may have simply handpicked biblical passages to prove his point. My rector Bill Van Oss, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Duluth, Minnesota, observes that other troubles have always taken a much greater toll on people. He says, “alienation, isolation and discrimination are some of the worst challenges human beings face,” and, he thinks, “scripture, especially the Gospels, point this out over and over.” So even if Wigglesworth and his ilk couldn’t see the typological wood for the trees, some Puritan ministers presumably focused on the abstract/general interpretations of biblical trials (such as isolation) rather than the concrete/specific ones (such as illness).

The link between early captivity narratives and suffering is widely accepted. In fact, scholar Adrian Weimer claims that “Perhaps the best-known colonial reflection on affliction is Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative.” This haunting quotation from Rowlandson’s conclusion illustrates the human cost of enduring that pain.

Before I knew what affliction meant, I was ready sometimes to wish for it . . . and that Scripture would come to my mind, Heb. 12. 6. For whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth, and scourgeth every Son whom he receiveth: but now I see the Lord had his time to scourge and chasten me. The portion of some is to have their Afffliction by drops, now one drop and then another: but the dregs of the Cup, the wine of astonishment, like a sweeping rain that leaveth no food, did the Lord prepare to be my portion. Affliction I wanted, and Affliction I had, full measure (I thought) pressed down and running over.

This excerpt also points out the dual functions of Rowlandson’s narrative as both a jeremiad (lecture) illustrating physical captivity and a spiritual autobiography illustrating the soul’s bondage to the body. For ironically, the longer Rowlandson’s body was held in thrall, the more her soul was liberated and her faith deepened.

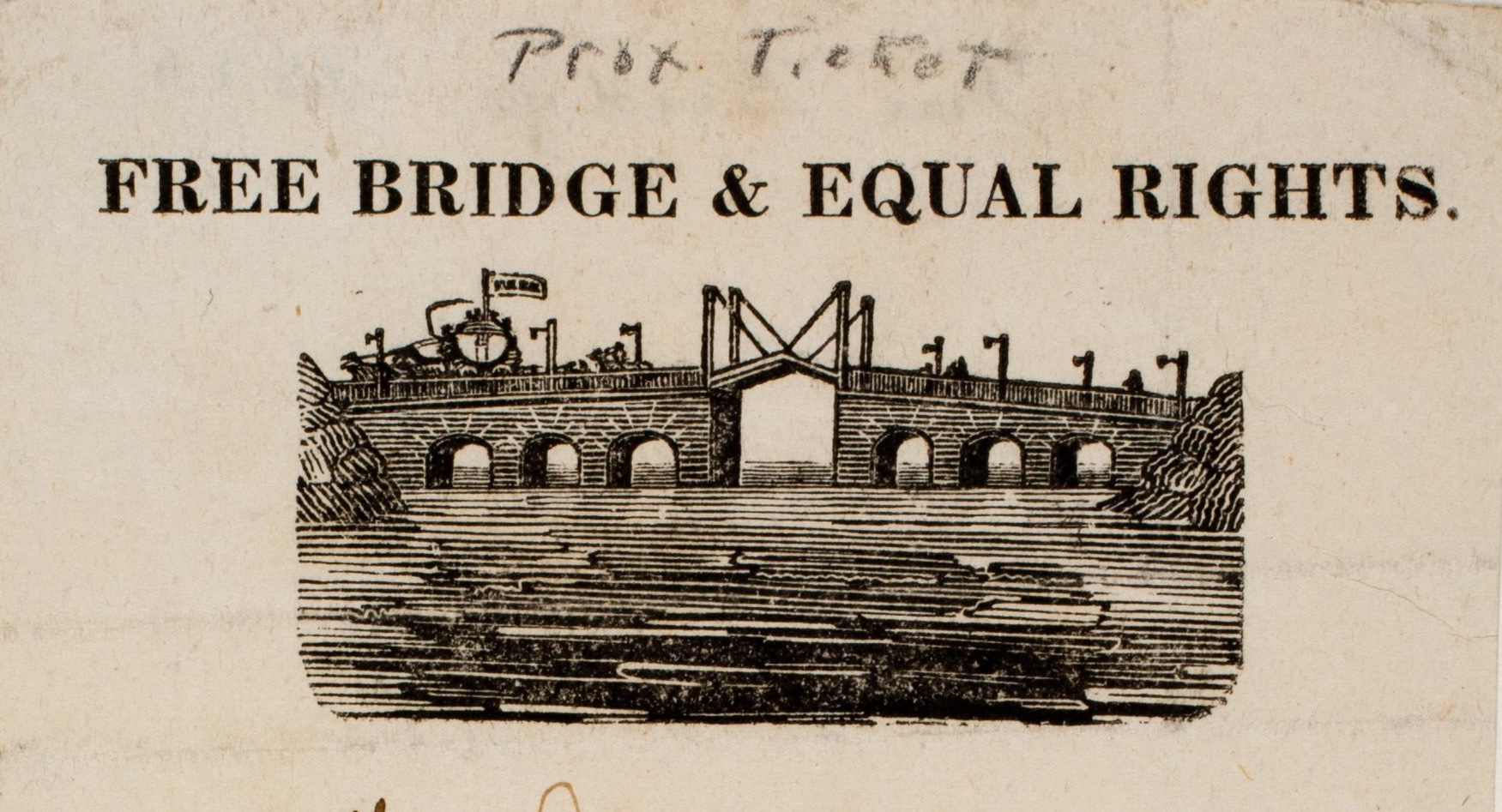

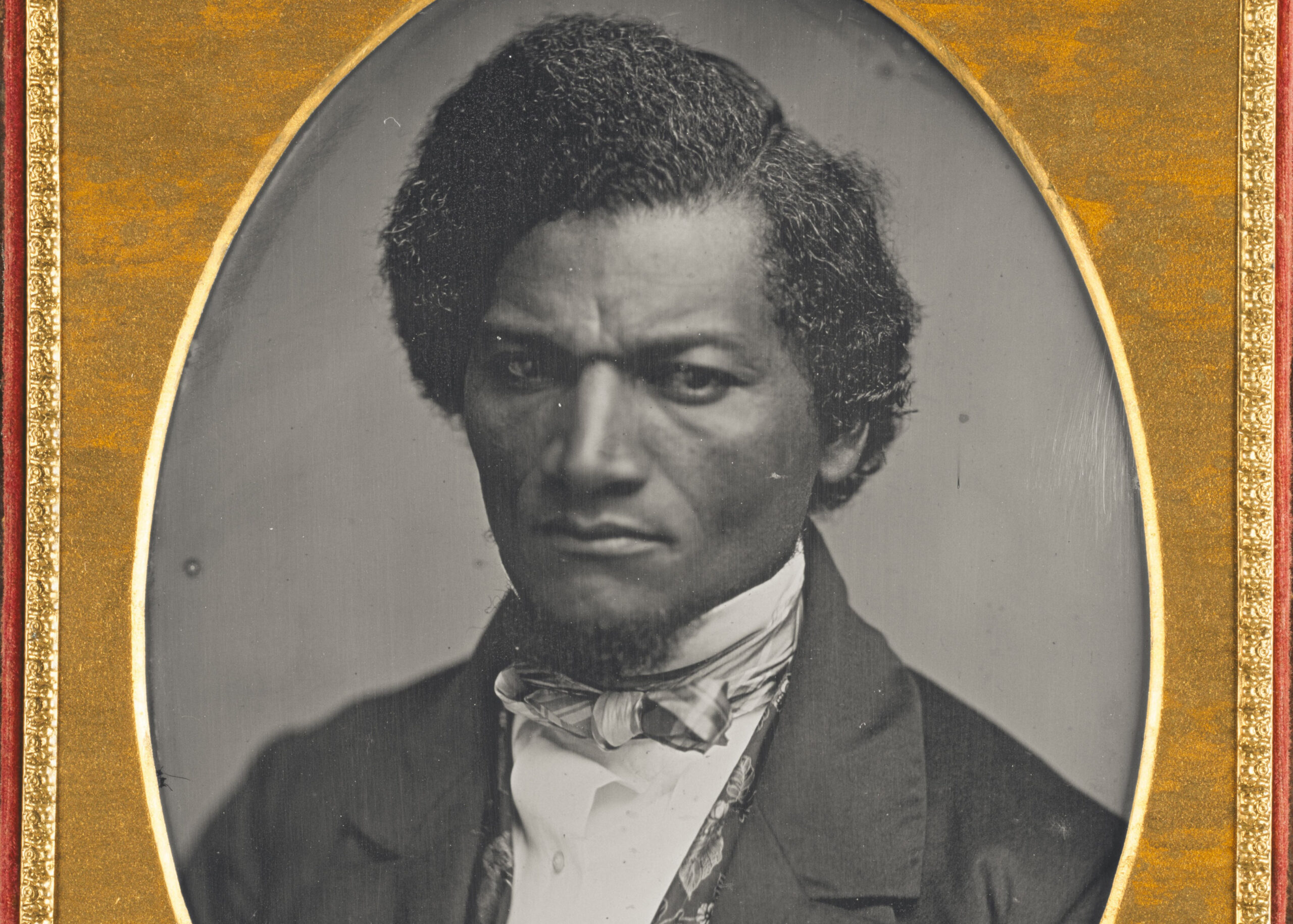

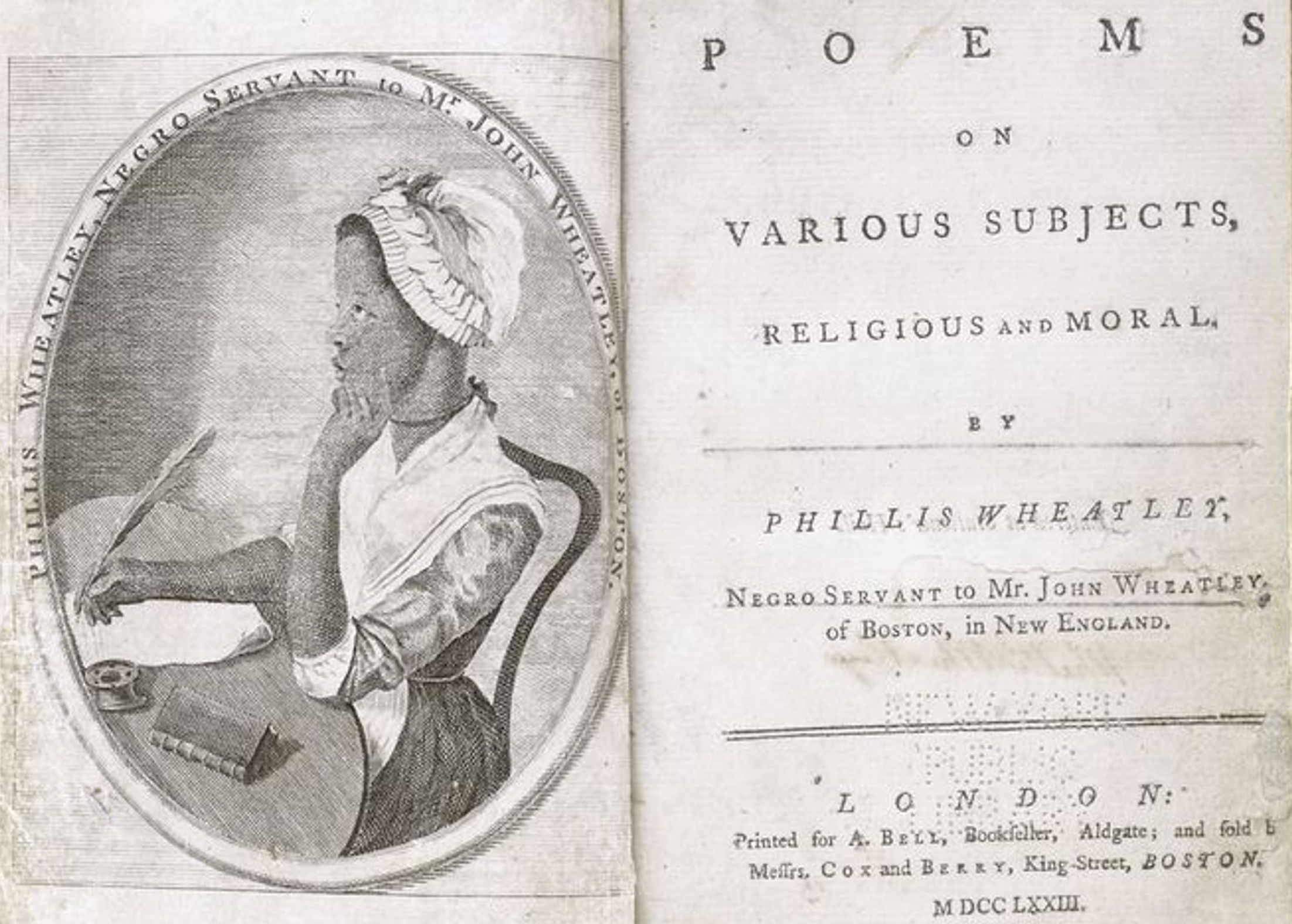

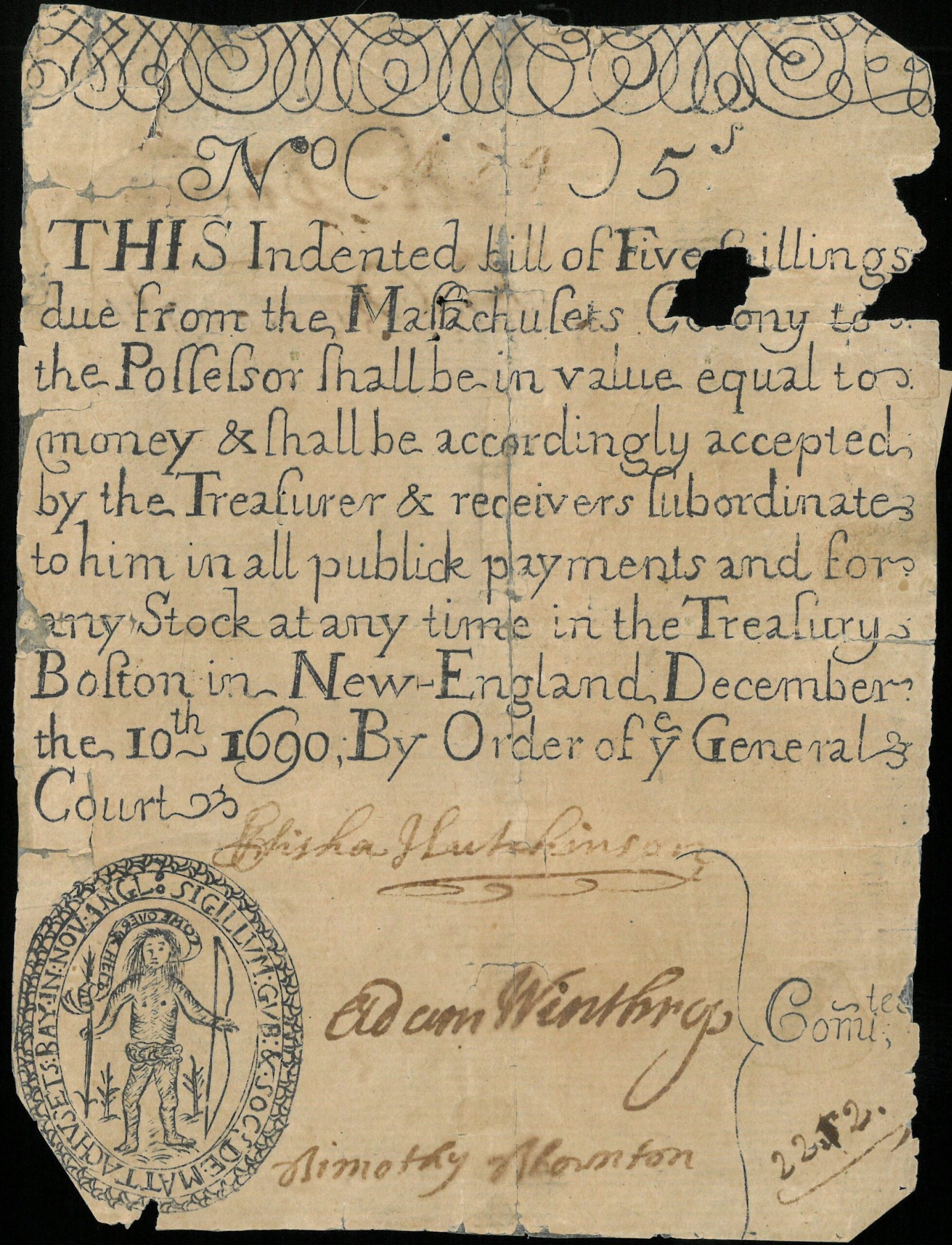

Since the connections between affliction and captivity are so well established, I focus in the rest of this essay on the less studied topic of incapacity and illness. Cotton Mather, one of Rowlandson’s contemporaries and one of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s premier ministers, writers, scientists, and intellectuals, argues in Mens Sana in Corpore Sano: A Discourse upon Recovery from Sickness (1698) that people receive both secular and spiritual blessings through ill health and recovery (figs. 3, 4). Indeed, by tying maladies to transgressions, he sought to persuade wrongdoers that their choices led to bad physical and spiritual health, and that affliction might be at least partly self-inflicted. According to Mather, God goads us into seeking forgiveness for our wrongdoing when He delivers us from sickness instead of letting us die in a sinful state. Using extended metaphors of disease and healing, Mather traces a causal line from original sin to the medical conditions of his day, as in this example, “If Crudities, [digestive problems and flatulence] and Obstructions, and Malignities, are the Parents of our Sicknesses, ‘tis very sure, that Sin is the Grand Parent of them, and the Sin of our First Parents is the First Parent of them all.” He continues by drawing even closer correspondences between certain sins and their manifestations, “Original Sin, is the Plague of the Heart. Every Lust, is a Distemper [throat ailment or diphtheria] of the Soul. An Unsteady Soul has a Palsey. A Wanton Soul, has a Feaver. A Worldly Soul has a Dropsy [fluid build-up]. An Angry Soul, has an Erysipelas [feverish skin infection]. Envy, is a Cancer in the Soul.” The metaphorical power of envy corroding the soul as cancer corrodes the body is particularly dramatic and compelling.

Yet Mather also acknowledged that mental and physical illnesses sprang from natural causes. Perhaps his attempts to scientifically categorize and theologically contextualize such origins led him to undertake the project that became The Angel of Bethesda: An Essay upon the Common Maladies of Mankind. Begun in the 1690s and completed in 1724, this work has sixty-six chapters, though several sections, including the one on cancer, are now lost. The work remained unpublished until 1972. But we know from the index that Mather titled the missing chapter on cancer “Magor-Missabib. Or, The Cancer,” which can be translated as “terror on every side.” How apt that naming cancer in this way so powerfully captures its nature as a relentless and merciless enemy.

The Angel of Bethesda dramatizes the growing conflict between medical providentialism and scientific rationalism in the early eighteenth century. As shown in Marc Priewe’s book Textualizing Illness: Medicine and Culture in New England 1620-1730, Mather tried to resolve these inherent contradictions in various ways. First, he believed that symptoms could be relieved by natural (but not, of course, occult) remedies that God revealed to physicians and others. So it was not a sin to seek relief from suffering, even though a respite could only be temporary if the underlying spiritual malaise were not addressed. Second, Mather established “a theory of disease” and claimed that illnesses originated in a fluid-filled border between the soul and the body that he called the “Nishmath-Chajim,” which is Hebrew for “breath of life.” Third, he described the ways in which individuals and the society they lived in became zones through which various forces from the natural and supernatural worlds might enter, including illnesses. He may have reached these conclusions following his involvement in the debate over smallpox inoculation a few years earlier. During 1721 and 1722, the medical and ministerial communities in Boston vehemently argued the pros and cons of vaccination to halt smallpox epidemics. Mather placed himself in the scientific vanguard when he supported such preventive measures and seemed to challenge determinism by valorizing human agency (free will) to combat such a scourge.

Siddhartha Mukherjee’s masterful history of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies (2010), explains that while evidence of cancer goes back to the ancients, it was only named around 400 BCE, in Hippocrates’s time. Etymologically, even then the name cancer, meaning crab, suggested a tenacious disease and a formidable adversary. What the Greeks, and the Puritans twenty centuries later, referred to as “cancer” or “a cancer” did not necessarily possess the same meanings as today. Yet it turns out that cancer continues to be a shape shifter, so that its definitions are constantly in flux. Mukherjee states that in ancient Greece “cancers” meant “mostly large, superficial tumors that were easily visible to the eye” and that could as easily be benign as malignant. By approximately 160 CE, the physician Galen extended Hippocrates’s theory of the four humours and held that cancer arose from an internal systemic imbalance of black bile resulting in external swellings. Since it was thought that excising tumors would not counteract the systemic accumulation of bile, surgery was not usually recommended. Instead, apothecaries prepared a range of remedies. In the sixteenth century, the Swiss doctor Paracelsus challenged the theory of humours and established a theory of disease based on chemistry.

According to Patricia Watson, however, Puritan medics still subscribed largely to Galenic medicine. Their healing practices often relied on local plants, so that knowledge of herbalism (and the handbooks called herbals or, more formally, pharmacopoeia) was important. Further, Puritan physicians might utilize and pass on remedies they themselves had created or had gleaned from other sources, leading to what Watson terms a “remedy-exchange network.” Within the colonies in the seventeenth century, a few physicians also subscribed to the Paracelsian school of “iatrochemistry,” literally “chemical medicine,” a field that originated in alchemy and that believed in chemical solutions to disease. Both Galenic and Paracelsian theories raised questions about the efficacy of cures and about individual genetics versus environmental factors in causing disease.

But the best source of information about cancer in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries occurs in Alanna Skuse’s 2015 book Constructions of Cancer in Early Modern England: Ravenous Natures. Although she does not explicitly cover New England, we can assume that transatlantic travel and communication at the time meant that at least some of the thinking and writing about causes, cases, and cures made it to America. Because most diagnosed cancers then were visible or palpable at or just beneath the body’s surface, much of the information on the disease concerns skin, breast, and facial tumors. Skuse agrees with other scholars’ conclusions that in early modern times a woman’s body, particularly her breast, was “the paradigmatic site of cancerous growth.” Indeed, she claims that most of the recorded cases of cancer concerned women. My own research also indicates that for a host of social, cultural, medical, and biological reasons, what was diagnosed as breast cancer figures more frequently than other cancers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Likely, the sexual and maternal symbolism of the breast that originated in the Bible through the conflicting female identities of Eve (lover) and Mary (mother) account for such attention in early modern texts.

Consider, for example, the complicated nexus of interpretive possibilities in the following treatment for cancer mentioned in the Salem physician Zerobabel Endecott’s 1677 “Synopsis Medicinae: Or a Compendium of Galenical and Chymical Physick,” a compilation of medications he left in a manuscript which was first published in 1914: “A woman at Casko bay had a Cancer in her breast which after much means used in Vain they applied strong beer to it with Double Cloths which it drank in Very Greedily & was something eased afterwards beer failing they Used Rum in Like manner which seemed to Lull it a sleep afterwards they put Arsenic into it & dressing it twice a day it was Perfectly whole in the mean time her Kind husband by Suking drew her breast with ye Loss of his Fore teeth without any farther hurt.” An alcoholic breast that responds first to beer, then to rum, and finally to arsenic? No, rather a description of what could be seen as an exclusively sexual act but is also a compassionate if not filial one in which a man/baby suckles his wife’s breast and sacrifices his front teeth to save it.

The disease also attracted Cotton Mather’s attention primarily because his beloved first wife, Abigail, was sick for months from what was apparently breast cancer. In his diary entry on October 22, 1702, he wrote of a dream she had in which a “grave Person” appeared to her and suggested ways to relieve her suffering, “First, for her intolerable Pain in her Breast, said he, let them cut the warm Wool from a living Sheep, and apply it warm unto the grieved Pain. . . . She told this on Friday, to her principal Physician; who mightily encouraged our trying the Experiments. We did it; and unto our Astonishment, my Consort revived at a most unexpected Rate.” Unfortunately, the improvement was short-lived and Abigail died that December. Mather’s diary entries on his wife’s decline reveal his torment about what wrongdoing within his family circle might have brought on such a trial. And his diary notations on other parishioners stricken with cancer show that the disease elicited particular sympathy from him and led him to reflect further on the link between sin and affliction.

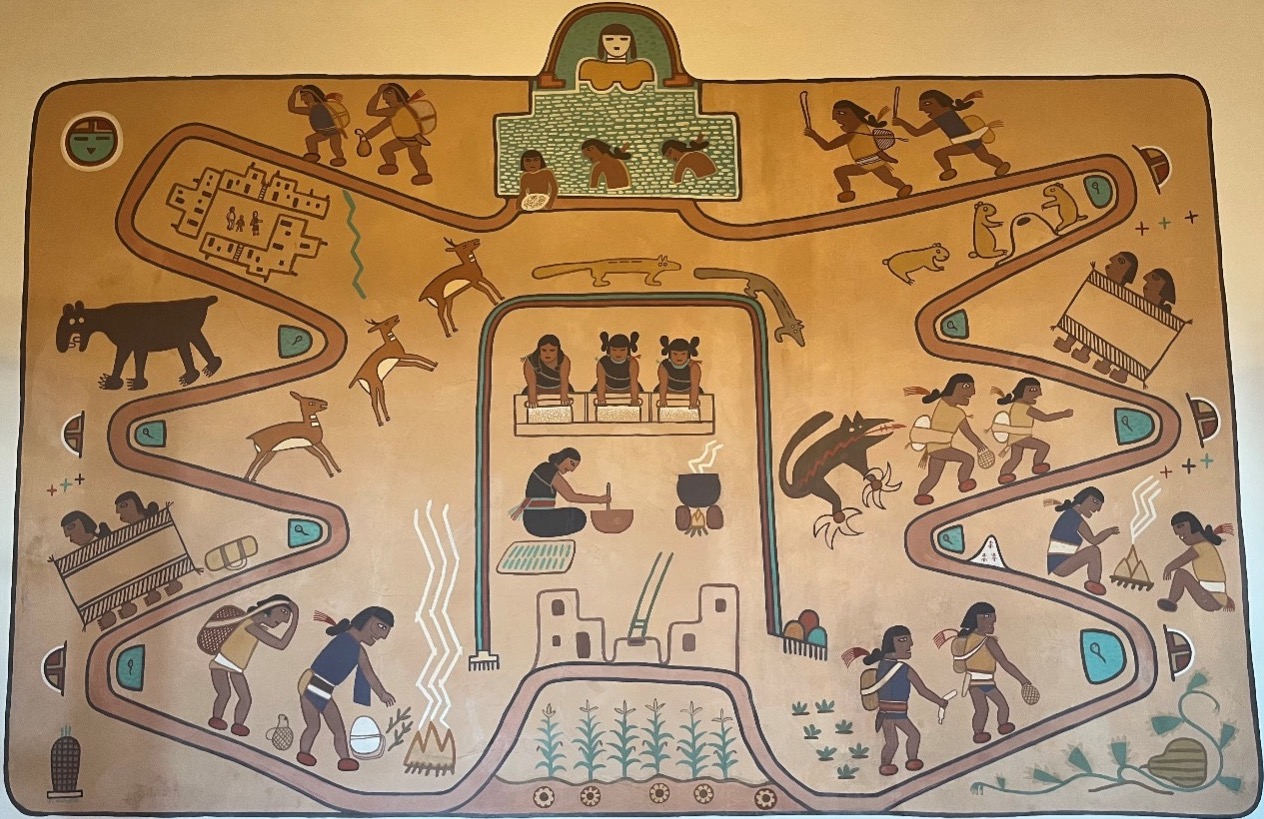

My wise friend Pattie Cowell was treated for ovarian cancer more than twenty years ago. Happily, she remains cancer-free today. An academic and early Americanist like me, in 1999 Pattie published a personal essay on her experiences titled “Deep Focus” in the creative writing journal Prairie Schooner. Here’s how she responded when I first floated the idea of “Cancer and Captivity” past her: “Seems to me we humans most always ‘capture’ our lives in the narratives we’re familiar with. . . . I framed mine around ideas of story-telling, probably because I’ve been fascinated for years by the many ways literature (that is, narrative) shapes or gives us a framework for expressing our concepts of lives and experience.” Correspondingly, for decades I’ve been drawn to works about captivity and confinement because, as I wrote in the preface to my book The War in Words: Reading the Dakota Conflict through the Captivity Literature (2009), these intriguing texts “enact culture clashes, culture-crossing, cultural confusion, and cultural exchange.” The cultures I had in mind were ethnic and to some extent drew from my own mixed Armenian, English, German, and Irish background. I could never have anticipated that the culture of cancer with all its specialized terminology, treatments, and practices could ever be part of my research or that I could apply elements of captivity to my own experiences.

The long-term effects of captivity on Rowlandson are unknown. Some scholars speculate that she married a military man, rather than a minister, the second time around because she sought physical protection from the kind of attack that had led to her three-month confinement. Certainly the final sentences of her narrative, written soon after her return, show a deeply troubled woman filled with secular and spiritual anxieties. I don’t believe (as some do) that storytelling anesthetizes people from their ills, but I do believe it can restore some sense of control they lost during their trials. That empowerment is elusive, of course, and for Rowlandson at least it functioned as a means to deeper spiritual growth. Indeed, she would have held that writing-as-witness was far more valuable than writing-as-therapy. So her narrative needed to show that she had been transformed by her experience, that she was a better person, a better Puritan, for it.

The only conclusion I can draw from being a cancer survivor is that while experience may affect identity, it does not erase or even, in my case, improve an earlier self. I cannot accept that a loving creator would make people suffer just to get their attention or to punish them. So of course I reject outright Cotton Mather’s astonishing claim in Mens Sana in Corpore Sano that “Diseases may be Love Tokens” from God (fig. 5). But I do admit that I felt myself sustained throughout my affliction, though by what, I’m not sure. During a brief respite from dealing with the illness and death of many relatives (including her beloved daughter’s diagnosis of breast cancer and subsequent mastectomy), Abigail Adams wrote on December 8, 1811, to her son John Quincy, “amidst this complicated Scene of distress, grief and Sorrow, I am alive to relate it—Spared Sustained, Supported beyond what I could conceive—yet my Heart has bled at every pore” (fig. 6). I too emerged on the other side of my sickness “alive to relate it” and reasonably intact physically, emotionally, and spiritually. I am grateful.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Pattie Cowell, Annette Kolodny, and Dan Williams, who provided helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Further Reading

The text of Mary Rowlandson’s captivity narrative can be found in many places online and in hard copy. For hard copy versions with helpful introductions and notes, I recommend Neal Salisbury’s edition of The Sovereignty and Goodness of God . . . (Boston, 1997) and the text in my own collection, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives (New York, 1998).

Elizabeth Weil’s New York Times Magazine article about Lisa Bonchek Adams is titled “Follow Me: She Taught Us How to Die” (December 27, 2015). Barbara Ehrenreich’s article “Smile! You’ve Got Cancer” appeared in The Guardian on January 1, 2010.

The scant number of studies about Michael Wigglesworth includes Edmund S. Morgan’s edition, The Diary of Michael Wigglesworth 1653-1657: The Conscience of a Puritan (New York, 1946); Richard Crowder’s biography, No Featherbed to Heaven: A Biography of Michael Wigglesworth, 1631-1705 (East Lansing, Mich., 1962); Ronald A. Bosco’s edition, The Poems of Michael Wigglesworth (Lanham, Md., 1989); and a recent article in Early American Literature by Adrian Chastain Weimer, “From Human Suffering to Divine Friendship: Meat out of the Eater and Devotional Reading in Early New England” (2016).

My article on Rowlandson’s mental state is “Puritan Orthodoxy and the ‘Survivor Syndrome’ in Mary Rowlandson’s Indian Captivity Narrative,” in Early American Literature (1987). See also Cynthia L. Ragland, “The Urban Captivity Narratives: The Literature of the Yellow Fever Epidemics of the 1790s” in Colonial and Post-Colonial Incarceration, edited by Graeme Harper (London, 2001), and Sarah Schuetze, “’The Fever and the Fetters’: An Epidemiology of Captivity and Empire,” in Women’s Narratives of the Early Americas and the Formation of Empire, edited by Mary McAleer Balkun and Susan C. Imbarrato (Basingstoke, England, 2016).

See these two works by Cotton Mather, Mens Sana in Corpore Sano (Boston, 1698), and Cotton Mather: The Angel of Bethesda: An Essay upon the Common Maladies of Mankind, edited by Gordon W. Jones (Barre, Mass., 1972). Also note Otho T. Beall and Richard H. Shryock’s biography Cotton Mather (New York, 1979). Many studies examine Cotton Mather’s medical contributions, including his involvement in smallpox inoculation: Ola E. Winslow, A Destroying Angel: The Conquest of Smallpox in Colonial Boston (Boston, 1974); Jennifer Lee Carrell, The Speckled Monster: A Historical Tale of Battling Smallpox (New York, 2003); Tony Williams, The Pox and the Covenant: Mather, Franklin, and the Epidemic that Changed America’s Destiny (Naperville, Ill., 2010); Kelly Wisecup, Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literature (Amherst, Mass., 2013); and the chapter “Thresholds of Modernity: Cotton Mather’s Medical Writings” in Marc Priewe, Textualizing Illness: Medicine and Culture in New England 1620-1730 (Heidelberg, Germany, 2014).

For works on the history of medicine in early New England, see John B. Blake, Public Health in the Town of Boston: 1630-1822 (Cambridge, Mass., 1959); Patricia A. Watson, The Angelical Conjunction: The Preacher-Physicians of Colonial New England (Knoxville, Tenn., 1991); Karen Gordon-Grube, “Evidence of Medicinal Cannibalism in Puritan New England: ‘Mummy’ and Related Remedies in Edward Taylor’s ‘Dispensatory,’” Early American Literature (1993); Linda Myrsiades, Medical Culture in Revolutionary America: Feuds, Duels, and a Court-Martial (Cranbury, N.J., 2009); Oscar Reiss, Medicine in Colonial America (Lanham, Md., 2000); Walter W. Woodward, Prospero’s America: John Winthrop, Jr., Alchemy, and the Creation of New England Culture, 1606-1676 (Chapel Hill, 2010); and Marc Priewe, Textualizing Illness: Medicine and Culture in New England 1620-1730 (Heidelberg, Germany, 2014).

For studies dealing with various aspects of the history of cancer, see Edith B. Gelles, Portia: The World of Abigail Adams (Bloomington, Ind., 1992); James Olson, Bathsheba’s Breast: Women, Cancer, and History (Baltimore, 2005); Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer (New York, 2010); and Alanna Skuse, Constructions of Cancer in Early Modern England: Ravenous Natures (Basingstoke, England, 2015). Skuse’s publisher, Palgrave Macmillan, has made her work available as an open source text.

See Zerobabel Endecott’s 1677 medical compendium, Synopsis Medicinae: Or a Compendium of Galenical and Chymical Physick (Salem, Mass., 1914), with an introduction and annotations by George Francis Dow, and also Diary of Cotton Mather with a preface by Worthington Chauncey Ford (New York, 1911), and The Diary of Samuel Sewall, edited by M. Halsey Thomas (New York, 1973).

Pattie Cowell’s essay “Deep Focus” appeared in the summer 1999 issue of Prairie Schooner.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.2 (Winter, 2017).

Zabelle Stodola is professor of English, emerita, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and currently an independent researcher living in northern Minnesota. She is the author of six books, most recently the co-edited volume A Thrilling Narrative of Indian Captivity: Dispatches from the Dakota War (2012). From 2003 to 2005, she was president of the Society of Early Americanists.