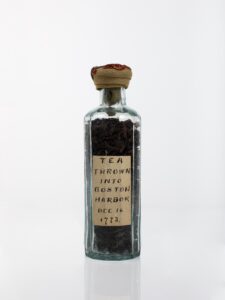

In the summer of 1815, a “strange incident” occurred in Pittsfield, on the western edge of Massachusetts. The news of an “interesting discovery of a Jewish phylactery” at Pittsfield’s “Indian Hill” neighborhood soon “excited much discussion among theologians and awakened the vigilant researches of antiquaries,” including multiple members of the newly formed American Antiquarian Society (AAS). That fall Elkanah Watson, who was then living in Pittsfield, wrote his fellow AAS member Hugh Williamson, in South Carolina, to relay the details. He described examining the object, which consisted of leather strap and pouch containing small parchment scrolls “inscribed with texts of Scripture, written in Hebrew.” That a phylactery or tefillin, which is usually worn for Jewish prayers, had been unearthed in an area with only one Jewish resident in recent memory seemed unusual indeed. Yet Watson and the other antiquaries and theologians made quick sense of what they found: an item forming “another link, in the evidence by which our Indians are identified with the ancient Jews who . . . to this day remain a living monument, to verify and establish the eternal truths of Scripture.” Accordingly, in 1816 the precious Pittsfield phylactery was deposited in the AAS antiquities collection across the state in Worcester for safekeeping and study (it now resides at Harvard’s Peabody Museum).

Collecting for Salvation: American Antiquarianism and the Natural History of the East

The outlines of “salvation antiquarianism”—with the emphasis on “saving” both in terms of preservation and Christian redemption—appears particularly clearly in the AAS’s inaugural 1813 address.

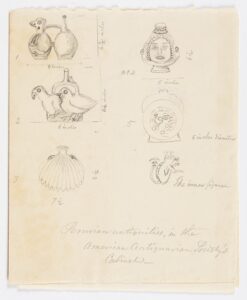

Much was written about the “Jewish Frontlet” in the following years, and numerous scholars attempted to consult it at the AAS, where it was housed alongside other early donations such as an “Antique Indian Axe of the Choctaw Nation,” an “Indian pounder” from West Boylston, and cloth “manufactured by the Natives of the Sandwich Islands.” The “strange incident” in Pittsfield stirred the imaginaries of theologians and antiquaries alike because it supported millennialist Christian nationalism. Indeed, the phylactery allegedly provided physical proof that America’s Native peoples were “ancient Jews,” and this in turn offered empirical confirmation of the Bible’s “eternal truths.” This was an old trope: Atlantic scholars since at least the sixteenth century had proposed an Old World origin for America’s original peoples, including one that saw Indigenous ancestors trekking from the “Holy Land” across Asia and the Behring Strait to America, all the while “adhering to the rites of the Jewish Religion,” as Watson explained. Historians Eran Shelav and Shalom Goldman, moreover, have documented the ubiquity of “Hebraic” political rhetoric in early America, while Andrew Lewis, Sarah Rivett, and others have documented the significance of Old-New World theories to transatlantic colonialism and science.

Given the popularity of the “lost tribes of Israel” hypothesis in colonial America (as recently described by historian Elizabeth Fenton) and its revival during the Second Great Awakening, the phylactery’s inclusion in the AAS Cabinet—as a suspected “aboriginal” item—is unsurprising (it was rumored to have been buried with an “old Indian chief,” which is not true). AAS member and president of the American Bible Society Elias Boudinot (who was also the sponsor and namesake of Cherokee Phoenix editor Buck Watie/Elias Boudinot) expounded on “Hebraic Indians” in his influential A Star in the West, Or, a Humble Attempt to Discover the Long Lost Ten Tribes of Israel: Preparatory to Their Return to Their Beloved City, Jerusalem (1816). Boudinot’s words were repeated in Ethan Smith’s best-selling View of the Hebrews; Or, The Tribes of Israel in America (1823) (and later reworked re-worked by Pequot minister William Apess in the Appendix to his 1829 memoir A Son of the Forest), and Smith’s 1825 edition referenced the Pittsfield phylactery in detail. The phylactery’s inclusion in the AAS collection thus illustrates a larger ideology in which Anglo-American settler society is positioned within a divinely-sanctioned order and helps create what historian William N. Goetzmann called “a religious vision of American prehistory.”

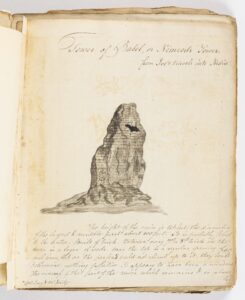

The phylactery’s inclusion in the AAS cabinet tells us more about early US antiquarianism than just its exclusionary anti-Indigenous and anti-Semitic origins, and a consideration of the early collection provides a wider angle on its political project. When the AAS was established in 1812, it was with the mission “to discover the antiquities of our own Continent . . . as well as to collect and preserve those of other parts of the Globe.” The “Jewish Frontlet” was accessioned along with Indigenous heritage items and other donations including an inscription from a Babylonian ruin, a lock taken “from the church of the holy sepulcher in Jerusalem,” “Relicks of a real Egyptian mummy,” and a Canton trade passport from the ship John Jay, these latter items evincing the conflation of the non-Christian Mediterranean world with the large mass of non-Christian Asian lands stretching from Persia to China. Certainly, the allegedly “backward” non-Christian world has long been a crucial foil to the United States’ conception of its own modernity, and it is thus unsurprising that an item for Jewish worship would have been unceremoniously held next to a preserved body and trading papers. This interchangeability and desacralization of non-Christian materials was part of the point, for it allowed US Americans to portray “their” (Indigenous) past as equal to all ancient global cultures and their national present as best. Symptomatic is an exchange between Elias Boudinot and AAS president Isaiah Thomas in 1819: when Boudinot requested to examine the phylactery and Thomas was unable to locate it among the cabinet’s boxes, he reportedly showed Boudinot an “ancient” Arabic manuscript instead. But the collapse of (Indigenous) American and Mediterranean “natural history”-style collectables here is not only about the intellectual pursuit of Indigenous origins: it is an expression of the United States’ early global and imperial ambitions, both with regard to the North American continent and to world markets, as well as an indication of the value of natural history collections to US political salvation. An exclusive focus on US settler colonialism without a critique of Orientalism, however, distracts from the imperialist context for US natural, and national, history.

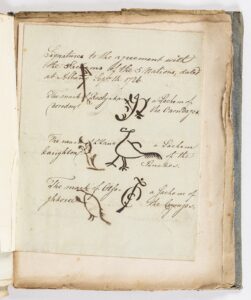

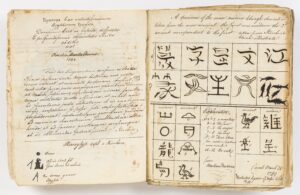

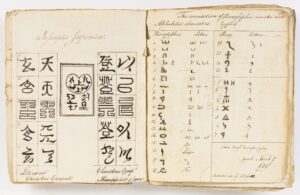

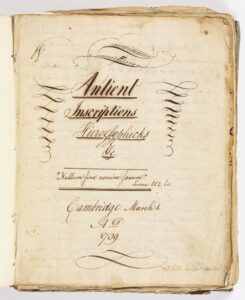

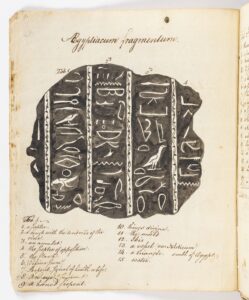

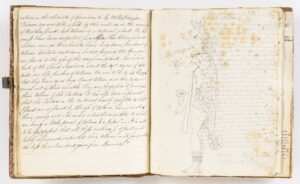

Massachusetts-born Thaddeus Mason Harris, one of the founding members of the AAS, spent as much of his life studying the history of the American continent as he did about the ancient world of the Israelites. Harris trained for the ministry at Harvard and served as the College’s librarian from 1791 to 1793 before becoming pastor at First Parish Church in Dorchester, a position he held until his death in 1836. As early as 1789, Harris began to explore his interests in “the first peopling of America” (although none of these interests saw publication until his 1805 Journal of a Tour Into the Territory Northwest Of The Alleghany Mountains, in which he suggested that America’s aboriginal peoples were descended from the “ancient Scythians” of Siberia). His commonplace book, titled “Ancient Inscriptions, Hieroglyphics, &c.” and held at the AAS, is a compilation of Orientalist studies, natural history, and antiquities that includes sections on customs, manners, and literature as well as Egyptian hieroglyphics, “Siberian languages,” Mexican history, and Indigenous American artifacts. While working on this project, however, and serving as Harvard’s librarian, Harris published something seemingly far afield from his North American speculations: The Natural History of the Bible, or, A Description of All the Beasts, Birds, Fishes, Insects, Reptiles, Trees, Plants, Metals, Precious Stones, &c. Mentioned in the Sacred Scriptures (Boston, 1793). True to the title, the entries focus on the plants, animals, and minerals mentioned in the Hebrew Bible. Taking the dictionary as its type—complete with a reference to Samuel Johnson in the introduction—each entry provides definitions, usage, and cross-references similar to a contemporary lexicon. Harris’s Natural History demonstrates a decidedly philological and ecological approach to biblical criticism, attempting to save Old Testament landscapes from European ignorance and restore them to new life in North America.

Harris belonged to a long line of Atlantic theologians who believed that the “Book of Nature” complemented the “Book of Revelation,” a common contemporary starting point even with the increasing secularism of late eighteenth-century transatlantic scholarly culture. He also believed that God’s Truth was reflected in human language. This particular kind of biblical scholarship, later known as “Higher Criticism,” was a form of Christian hermeneutics that embraced empiricism as the basis for biblical interpretation. During his theological studies, Harris had come to believe that previous English translations of the Old Testament had distorted Scripture’s true meaning due to insufficient knowledge of the natural landscape of the “Holy Land,” which at the time included all the areas of greater Syria, Arabia, Egypt, Nubia, and Abyssinia. Previous mistranslations of the Bible, Harris contended, obscured not only metaphors and felicities of ancient phraseology but had transmuted entire ecologies. Indeed, the authorized King James edition was so full of creatures with which “the Jews must have been wholly unacquainted”—like the badger and unicorn—that the effect was, at best, befuddling. Dragons, whales and apples, appearing in the place of crocodiles and citrons, placed the reader in seventeenth-century England, not ancient Palestine, and effectively miscommunicated God’s truth. Harris found, however, that consulting Hebrew etymology and the foundational Greek and Latin sources in combination with European naturalists’ reports from the East, “serve[d] to clear up many obscure passages . . . and open new beauties, in that sacred treasure.” To Harris, reconstructing a word’s relationship to climate and geography—as a cipher for the ancient Hebrews’ relationship to place—could restore previously uncommunicated knowledge. Just as the Pittsfield phylactery would, almost two decades later, the environment of the Holy Land would prove the “eternal truths of Scripture” and, crucially, America’s place in it.

Traditionally, the two projects to “clear up” the natural history of the Bible and the ancient history of the Americas have been understood as expressions of the universalism inherent to Enlightenment-era science, or seen in terms of typological exegesis wherein the United States is read as a latter-day Israel. But the coincident methods of biblical criticism and salvation antiquarianism on display in Harris’ life’s work trace a knowledge-making project that transmitted US exceptionalism across the continent and across the oceans: what he called the “natural history of the East” runs crosswise, not parallel, to contemporary efforts to establish an ancient American history.

At the time, there was little in the European naturalist tradition that supplied the sought information aside from Lemnius’ An Herbal for the Bible (1587), Rudbeck’s Icthyologia Biblica (1705), and Rauwolf’s Flora Orientalis (1755). The great Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus, who was concerned with expanding the natural history knowledge of the globe in the pursuit of a universal system for ordering Nature, personally encouraged his students to travel and gather widely. One of his students, Fredrik Hasselquist, traveled to Arabia from 1749 to 1752 (when he perished) for the Levant Company; his papers, “Containing observations . . . particularly on the Holy Land, and the Natural History of the Scriptures,” were published by Linnaeus in 1757 and translated into English in 1766. Another of Linnaeus’s students, Pehr Forsskål, traveled to Arabia from 1761 to 1763—in the employ of the Royal Danish Expedition—and his Flora Aegyptiaco Arabica was also published posthumously, in 1775. Harris relied on these works for his own Natural History, and also consulted travel narratives such as the one published by Scottish traveler James Bruce in 1790.

Indeed, as philosophers and economists such as Montaigne and François Quesnay studied “Asiatic stagnation” and “Oriental despotism,” eighteenth-century naturalists and travelers sought to add the southern circum-Mediterranean world to Europeans’ stores of plant knowledge—all taking advantage of the Ottoman Porte’s weakening control of the eastern (Levant) and western (African) lands in the mid-eighteenth century. Bruce, for example, collected specimens during his attempts to find the source of the Nile from 1768 to 1773. Natural history, certainly, has long been a strong arm of imperial power: collecting information about the Levant, for example, was a way for France and Britain to assert imperial control over the Mediterranean—explaining the vast collections of flora and fauna taken by Napoleon I during his 1798-1801 campaigns in Egypt and Syria—or to imaginatively “domesticate” disputed territory, as with Lewis and Clark’s 1804 Corps of Discovery over the far western expanses of the American continent.

Largely influenced by the popularity of Arabian Nights’ Entertainments (at least four American editions of which were published before 1800), British, French, and American travelers flooded the circum-Mediterranean in the eighteenth century, taking souvenirs and leaving behind travel narratives. From 1773 to 1775 Ward Nicholas Boylston, of the wealthy Massachusetts merchant family, traveled through Turkey, Syria, Palestine, Egypt and along the Barbary Coast to escape the war coming to Boston. He brought his souvenirs and self-proclaimed expertise back to his home state (and, in 1819, to the AAS cabinet). After the Revolutionary War, the growing crisis with the Barbary States and the situation of US captives in the Mediterranean continued to attract US attention eastward. Under President George Washington, Congress pledged $100,000 in annual tribute to Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis to protect US ships attempting to access the Levantine trade. In 1793 alone, eleven US ships and 100 US sailors were captured by so-called Barbary pirates. This conflict in the Mediterranean would result in the US’s first overseas military action in 1801—which Jefferson had been pushing for since 1785—and the establishment of a US Navy in 1794. Into the nineteenth century, news and literature inspired by the themes of the Barbary Wars competed and combined with “redemptive” interest in the Holy Land.

The outlines of “salvation antiquarianism”—with the emphasis on “saving” both in terms of preservation and Christian redemption—appears particularly clearly in the AAS’s inaugural 1813 address. Delivered by founding member William Jenks, Professor of Oriental Languages at Bowdoin College, it reiterated that the role of the antiquary was to “search out, preserve and transmit the discoverable traces of ancient knowledge” and to rescue Biblical knowledge from skeptical secular degradation by disproving accounts that tried to invalidate, scorn, or ridicule. And this goal of saving Scripture was never far from the rescuing of supposedly forgotten American history. Jenks expanded, “it may be found, that etymological enquiry, cautiously and diligently pursued, with a careful investigation of religious rites and ceremonies, and the prevailing manners, will connect the history of our Indian population with the ancient achievements of the early descendants of Noah.” With Jenks’s address as reference, it is easier to see that Harris’ use of etymology and his collection of all animal, vegetable, and mineral references in The Natural History of the Bible was meant, as sure as “Ancient Inscriptions,” to provide a universal account to bring America and the Holy Land together.

In 1816, the same year the “Jewish Frontlet” was sent to Worcester and Boudinot’s A Star in the West appeared in print, Harris delivered a sermon to the Female Society of Boston and the Vicinity for Promoting Christianity among the Jews. In the early nineteenth century, transatlantic Christians increasingly advocated for the conversion and “restoration” of Jews just as their ancestors had done for Natives since the seventeenth century. In Harris’s sermon, “Pray for the Jews,” he seems to compare the “saving” of conversion to antiquarians’ “saving” of history, counseling: “While zealously engaged in sending out into the wilderness to collect into the fold of Christ the sheep that are scattered abroad; let us cast a look after the lost sheep of the flock of Israel; and at least pray that Jew and Gentile may be brought to hear the voice and own the care of the same divine shepherd.” Indeed, the members of the newly founded women’s group, many of whom were involved with contemporary missionary organizations such as the Boston-based American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM), also considered themselves “collectors” in a way not altogether different from their antiquarian friend Harris (the Boston Female Society raised money to send Hebrew translations of the New Testament on the ABCFM’s 1819 “Palestine Mission”). While the Second Great Awakening is the usual context for this project of “collecting” Jewish souls and Holy Land “spiritual conquest,” it was also the period that saw the first coordinated attempts to remove the Israelites’ supposed descendants from their American homelands by “collecting” them into reservations or western lands, all to make way for the new Jerusalem in old Indian Country.

As Harris intensified his own studies of the “ancient Israelites” in the early nineteenth century, he updated his Natural History in 1820 (although most of the copies were destroyed in a fire at the publishing house). A transitional and transhistorical text bridging theology, philology, naturalism, and antiquarianism, Harris’s Natural History of the Bible—which enjoyed a long life in pirated and abridged editions—helps explain the coexistence of Indigenous heritage items, natural history specimens, and souvenirs from the Mediterranean world in East Coast learned society collections, collections that themselves trace a zealously exceptionalist relationship between America and “the East.” In the period signaled by Harris’ two editions—1793 and 1820—the United States was urgently trying to figure out its policy with regard to the (eastern) Barbary States as well as the (western) Native nations living on lands increasingly claimed as US territory. In this context, studying ancient natural history and establishing natural history cabinets isolated “East” and “West,” sequestering these areas and their histories from the contemporary world order, domesticating them as intellectual topics rather than polities representing existential threats to the early nation. The Natural History of the Bible reveals the ideological, rather than the philosophical or exegetical, collapse of Mediterranean and American geographies, and it provides an opportunity to reframe understandings of antiquarianism and natural history within a global exceptionalist model. Harris’s salvation antiquarianism was a divinely-driven hermeneutic that insisted God’s Truth would be made manifest through its application across the Americas and the Bible’s lands. For Harris, the true version of ancient history would be the one saved by the United States.

Further Reading

Robert Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

Jodi Byrd, The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Charles Crawford, Essay on the Propagation of the Gospel, in which there are Numerous Facts and Arguments Adduced to prove that many of the Indians in America are descended from the Ten Tribes (1799).

Elizabeth Fenton, Old Canaan in a New World: Native Americans and the Lost Tribes of Israel (New York: New York University Press, 2020).

Pliny Fisk, The Holy Land an Interesting Field of Missionary Enterprise: A Sermon Preached in the Old South Church, Boston, Sabbath Evening, Oct. 31, 1819, Just Before the Departure of the Palestine Mission (Boston: 1819).

Lee M. Friedman, “The Phylacteries Found at Pittsfield, Mass.,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (no. 25, 1917): 81–85.

William N. Goetzmann, “The Case of the Missing Phylactery,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society 95 (1985): 69-79.

Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

William Jenks, An Address to the Members of the American Antiquarian Society, Pronounced in King’s Chapel Boston, on Their First Anniversary, October 23, 1813 (Boston: 1814).

Amy Kaplan, Our American Israel: The Story of an Entangled Alliance (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018).

Andrew Lewis, A Democracy of Facts: Natural History in the Early Republic (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylania Press, 2011).

Hilton Obenzinger, “Holy Land Narrative and American Covenant: Levi Parsons, Pliny Fisk and the Palestine Mission.” Religion & Literature 35 (no. 2/3, 2003): 241–67.

Sarah Rivett, Unscripted America: Indigenous Languages and the Origins of a Literary Nation (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Stephen Salaita, The Holy Land in Transit: Colonialism and the Quest for Canaan (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006).

Eran Shalev, American Zion: The Old Testament as a Political Text from the Revolution to the Civil War. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

Elkanah Watson, Men and Times of the Revolution; Or Memoirs of Elkanah Watson, Including His Journals of Travels in Europe and America from the Year 1777 to 1842 (New York: 1858).

This article originally appeared in October 2022.

Christen Mucher is Associate Professor of American Studies at Smith College. Her recent publications include the co-edited volume Decolonizing “Prehistory”: Deep Time and Indigenous Knowledges in North America (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2021) and Before American History: Nationalist Mythmaking and Indigenous Dispossession (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2022), part of the Sustainable History Monograph Pilot. Mucher was an NEH Fellow at the American Antiquarian Society in 2015. The author would like to thank Laura Costello, Cynthia Mackey, Nan Wolverton, and Joshua Greenberg.