Convalescent Calamus: Paralysis and Epistolary Mobility in the Camden Correspondence with Peter Doyle

In the fifth season of the CBS television drama Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman (1993-1998), starring Jane Seymour in the titular role, an episode titled “The Body Electric” opens with Walt Whitman (Donald Moffat) arriving in Colorado Springs for a week-long stay at the local “Springs Chateau and Health Resort.”[1] Historically, the episode’s imagined detour through Dr. Quinn’s orbit coincides with a trip the poet made out west in 1879. Whitman had experienced a major paralytic stroke in January 1873, after which he was diagnosed with hemiplegia on his left side. As he slowly recovered some mobility, he remained partially paralyzed and required the use of a cane for walking. In the episode, the owner of the health resort, Preston A. Lodge III (Jason Leland Adams), has promised the poet free room and board—a complimentary Silas Weir Mitchell-inspired “rest cure”—in exchange for a poetry reading. “[H]e’s recovering from a stroke,” Preston announces to the townspeople, “and he’s chosen my resort to restore him to health.” Everything changes once rumors spread of the poet’s sexuality, and the episode transforms swiftly into a parable of tolerance. Being forewarned, the assigned physician, Dr. Andrew Cook (Brandon Douglas), cannot bring himself to shake Whitman’s hand. Later, in private, Andrew explains to Preston with earnest eyes, “Whitman is … peculiar.” “Peculiar?” Preston asks. “A deviant,” Andrew clarifies. “A deviant?” Preston inquires, puzzled. Andrew breaks it down as plainly as he can muster: “He prefers the company of men, if you understand my meaning.” Preston is aghast (fig. 1). The poetry reading is cancelled. By the end of the episode, civility is restored when Dr. Quinn overcomes her own intolerance and decides to host the poetry reading herself. None other than Peter Doyle (Steven Culp), in from Washington to visit his “soulmate,” convinces Dr. Quinn her prejudices have been misguided. Most importantly, Seymour’s ever-judicious Dr. Quinn recognizes that Doyle has had a medicinal influence on the poet: where “electrotherapy, hydropathy, phrenology” and her “hot pepper ointment” have failed, the presence of the comrade has succeeded in making Whitman feel well (fig. 2).

This episode of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman directs attention to the intersection between disability and sexuality in Whitman’s life and writing, which became especially prominent from the Civil War onward. Certainly, “The Body Electric” derives plenty of plot from what Desiree Henderson has described as the episode’s epistemology of the closet, the “phenomenon of ‘outing,’” which promises viewer satisfaction via “the spectacle of revelation.”[2] But “The Body Electric” also moves beyond this prepackaged plot. The dialogue gets a bit heavy-handed here and there. “Have you been using the ointment?” Dr. Quinn asks Whitman in her clinic one day. “Mmhmm,” Whitman replies. He then seizes the moment to make his paralysis into a metaphor: “But some things cannot be altered, dear doctor; you must learn to accept them as they are.” Overwrought as the dialogue may be, it accomplishes something scholarship on Whitman rarely has. When Preston cancels the poetry reading, he explains in a deliberate intermingling of references to the visitor’s paralysis with rumors of his same-sex attraction, “I had no idea the extent of your infirmity, and I see now that a public reading would be all too taxing for you.” When Whitman and Doyle are told they can no longer stay in the chateau, Dr. Quinn invites them to take a spare room in her clinic, instead, thus making the space of illness and medical care into a refuge for their sexual difference. Indeed, by its conclusion, the episode has nearly become a manifesto for the responsibility doctors have to educate themselves about and to adapt their practices to encompass queer health (fig. 3).[3] These intertwined themes beg the question, why is it that scholarship has generally neglected to put Whitman’s paralysis in direct dialogue with his literary representations of intimacy and eroticism, even as this intersection became central to his published writing, manuscripts, and correspondence?

The neglect is not exclusive to Whitman. Popular media is conspicuously lacking when it comes to acknowledging the sexual lives and identities of people with disabilities. As Robert McRuer and Anna Mollow have observed, we live with regimes of sexuality that presume able-bodiedness to be requisite to the experience of sex.[4] We are told “the sexiest people are healthy, fit, and active: lanky models, buff athletes, trim gym members brimming with energy.”[5] But even this description doesn’t quite do the matter justice. Popular media’s general reduction of the body to an object of capital-driven consumption has established, through assimilationist rhetorics of physical normalcy, a sexual imaginary disconnected from the diversity of human corporeality.[6] It is significant to note (considering Whitman’s current legibility as a historical gay icon) that this has been true of mainstream gay male culture, too. Under these representational norms, people with disabilities tend to be either desexualized or, conversely, imagined to signify sexual excess (via the fetishizing of impairment, the pathologization of desire in the context of disability, or the conflation of illness with rhetorics of sexual culpability). Discussing this paradox, Mollow observes, “These contradictory constructions of disability create a double bind for people with disabilities: if disability can easily be interpreted as both sexual lack and sexual excess (sometimes simultaneously), then it seems nearly impossible for any expression of disabled sexuality to escape stigma.”[7] Dr. Quinn’s dialogue illustrates this double bind: the line “I had no idea the extent of your infirmity” indicates both a negation of capacity and a euphemistic association of the paralyzed body’s capacity for desire with an unknowable “extent” of that body’s pathological state.

Whitman scholarship has sometimes contributed to these omissions. Consider, as an illustrative case, Gary Schmidgall’s biography Walt Whitman: A Gay Life, which draws a stark line between Whitman’s sexuality in youth in New York and the life he led after his paralytic stroke. “[T]o all things, especially to an active sexual life, an end must come,” he writes.[8] (As we will see below, this was not the case.) Of course, historically, Whitman’s writings have played a role as well. No text demonstrates this better than the 1858 series of fitness-advice articles published in the New York Atlas, discovered by Zachary Turpin in 2015, titled “Manly Health and Training: With Offhand Hints toward Their Conditions.”[9] Published under the pseudonym Mose Velsor, “Manly Health and Training” promises to educate readers in those habits necessary to achieve what Manuel Herrero-Puertas describes as the fantasy of the herculean “good life”: in Whitman’s words, “a perfect body, perfect blood—no morbid humors, no weakness, no impotency or deficiency or bad stuff in him.”[10] As Herrero-Puertas notes with a diachronic allusion to contemporary media, here we find Whitman’s Velsor avatar positioning himself as antebellum influencer, his column overflowing with banal advice and relentless enthusiasm.[11]

And yet, taken as a whole, Whitman’s corpus quickly begins to unravel this antebellum, self-help iteration of what scholars and activists today understand to be an ideology of ability.[12] The concept of disability was not available to Whitman in the way it is understood today, either as a capacious political category necessitating rights and protections or, in the context of critical theory, as an experience produced largely by structural barriers to access. Nevertheless, across the last three decades of his life especially, Whitman began to engage with and explore forms of disability in his writing. One of the most illuminating representations of this turn appears in the way Whitman began to embrace his paralysis as part of his authorial persona after his stroke in 1873. Whitman used the term “disablement” to describe his physical state in the years that followed and began to redefine his sense of self through the lens of his paralysis. In manuscripts, published writing, and letters from the mid-1870s onward, we find Whitman beginning to refer to himself as a “half-paralytic” with striking constancy. “[H]alf-paralytic as I am,” he says as an aside to his friend John Burroughs in June 1879.[13] During a trip to Niagara Falls in September 1880, Whitman would refer to himself as a half-paralytic in the conclusions to multiple letters back-to-back: “I am unusually well & robust for a half-paralytic—,” he writes to William Torrey Harris; “Am now pretty well for a half-paralytic,” he says to Frederick Locker-Lampson; and to Rudolf Schmidt, Whitman concludes the brief missive, “I am unusually well for a half-paralytic—.”[14] Ed Folsom’s digital archive reveals seventeen transcribed letters to and from Whitman that use the word “paralytic” and another fifty-seven letters written by or to Whitman that reference his “paralysis” from 1873 onward. Combined with his prose and poetry, these letters show Whitman resolving to claim and even flaunt his paralysis as a critical feature of his celebrity.

Whitman’s move to incorporate his paralysis into a public identity shares a notable resemblance with the reclamation of “crip” in contemporary disability theory today. Crip theory provides a critical vocabulary for challenging what Robert McRuer has termed “compulsory able-bodiedness,” a term designating cultural pressures to self-present within standards of normative capability.[15] One senses from these writings that Whitman would have felt a kinship with Nancy Mairs’s influential 1986 essay “On Being a Cripple.”[16] Discussing her multiple sclerosis, Mairs famously asserts:

I am a cripple. I choose this word to name me….People—crippled or not—wince at the word ‘cripple,’ as they do not at ‘handicapped’ or ‘disabled.’ Perhaps I want them to wince. I want them to see me as a tough customer, one to whom the fates/gods/viruses have not been kind, but who can face the brutal truth of her existence squarely. As a cripple, I swagger.

Circulated among correspondents ranging from John Burroughs to Alfred, Lord Tennyson, letters and manuscripts show Whitman identifying as a half-paralytic to establish a comparable public consciousness of his changing body, his personal appearance, and his gait. His paralysis shaped his orientation toward his most intimate relationships, too.

~ ~ ~

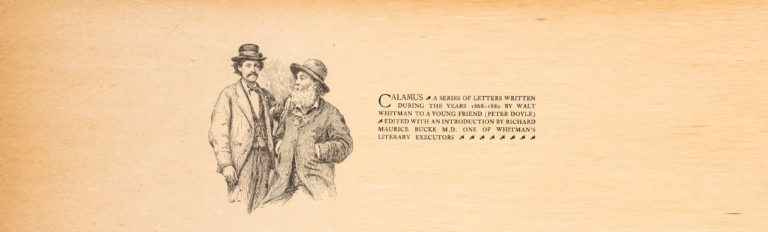

Much of my research in nineteenth-century American literature lies at the intersection of the medical humanities, sexuality studies, and historical understandings of illness and debility. In the spring of 2019, while conducting research at the American Antiquarian Society, I came across a book I had never held in person before. There are many writings in Whitman’s corpus that have the potential to change our perspective on how he understood the role of his paralysis in his relationships. This one was published in 1897, just five years after his death, by Whitman’s friend and disciple, Richard Maurice Bucke. Bucke (who alongside Horace Traubel and Thomas Harned served as one of Whitman’s literary executors) titled the book Calamus, a name taken from the sequence of poems in Leaves of Grass celebrating the expression of love between men, first appearing in the third edition printed by the publishing firm Thayer & Eldridge in Boston in 1860 (fig. 4). But the book is not a collection of those poems. Instead, as clarified by the subtitle “A Series of Letters Written during the Years 1868-1880 by Walt Whitman to a Young Friend,” the book features Whitman’s correspondence with Peter George Doyle, with whom Whitman developed a romantic friendship that would last from 1865 until the end of the poet’s life (fig. 5). The selected letters provide a biographical illustration of the kind of relationship Whitman intended to advocate in the “Calamus” cluster.

Bucke, a Canadian physician, became obsessed with the author of Leaves of Grass during the poet’s lifetime. The two met in 1877 and developed a friendship. Today, Bucke is best remembered as the author of a 1901 book called Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind, where he proposes an evolutionary horizon for humanity characterized by the state of mind named in his title. Superseding the mere “self-consciousness” of ordinary humans, “cosmic consciousness” describes a state where understanding of “the life and order of the universe” is attained, along with a “state of moral exaltation, an indescribable feeling of elevation, elation, and joyousness, and a quickening of the moral sense, which is fully as striking and more important both to the individual and to the race than is the enhanced intellectual power.”[17] A “sense of immortality” and fearlessness in the presence of death must likewise be present. According to Bucke, this cosmic consciousness describes a stage of evolution only a handful had reached by the twentieth century. Whitman was one of them. With ecstatic assuredness, Bucke asserts, “Walt Whitman is the best, most perfect, example the world has so far had of the Cosmic Sense, first because he is the man in whom the new faculty has been, probably, most perfectly developed, and especially because he is, par excellence the man who in modern times has written distinctly and at large from the point of view of Cosmic Consciousness, and who also has referred to its facts and phenomena more plainly and fully than any other writer either ancient or modern.”[18] Bucke even believed he could pinpoint the moment Whitman evolved. On an evening in 1866, an eye witness, Helen Price, recalled that Whitman began to emit a baffling luminescence over dinner: “a peculiar brightness and elation … an almost irrepressible joyousness, which shone from his face and seemed to pervade his whole body … I grew almost wild with impatience and vexation … he did not utter a single word during the meal; and his face still wore that singular brightness and delight, as though he had partaken of some divine elixir.”[19] Cosmic consciousness descended upon him that night.

Bucke didn’t just want to be like Walt. He wanted to look like Walt, and he didn’t do a shabby job of trying. An anecdote is appropriate here. In 2018, during a tour I organized for students at Swarthmore College of queer archives in Philadelphia, including the Walt Whitman Papers held at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, my students and I arrived shortly after Senior Curator Lynne Farrington had discovered an uncatalogued nineteenth-century photograph of a big-bearded man tucked away in one of the rare books.[20] The man appears seated outdoors, on a wooden chair mostly concealed, surrounded by vegetation and on the banks of a pond or lake (fig. 6). He holds a chipmunk on his raised right hand, a pose resembling the 1873 photograph Whitman appreciated of himself, holding a cardboard representation of a butterfly (fig. 7). In this case, one is left to speculate that the chipmunk has been preserved in its resting pose by taxidermy. “Who is this man whose pose parallels the author of Leaves of Grass?” students were invited to explore. By the end of our visit, Farrington had concluded: this was no Whitman photograph. This was Bucke. Better yet, this was Bucke in Whitman drag—what Farrington describes as the disciple’s “hero worship,” donned in the classic form of flattery through imitation.