Curiosity Did/Did Not Kill the Cat: The Controversy Continues

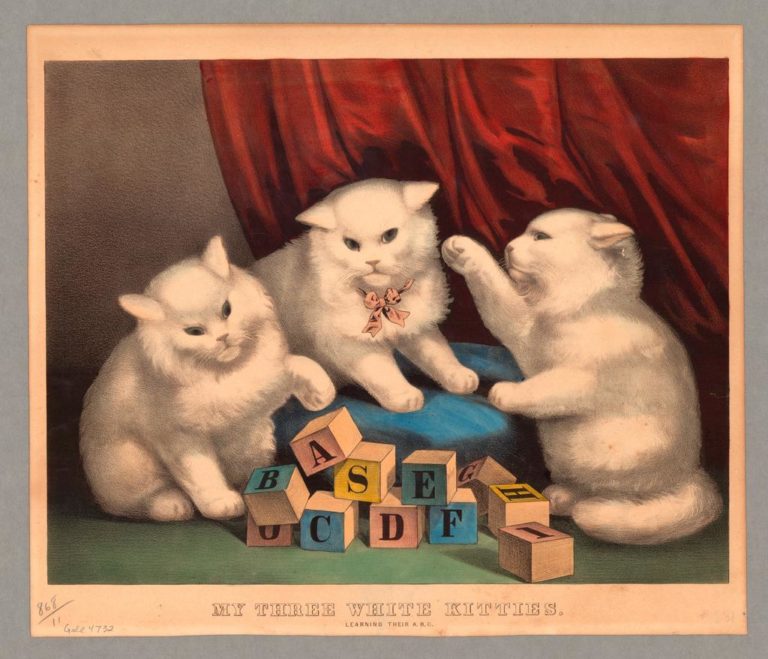

What is curiosity? “Curiosity” shares etymological roots with “care” and “careful;” once, a curious man was a fastidious one, a curious object an object well-wrought. Now, to be curious is to seek knowledge, but that knowledge, because acquired through curiosity, can been seen as illicit. It is a virtue to be curious, but curiosity killed the cat, and left Curious George locked up at the zoo, on display for curious children and their curious parents.

Curiosity works likes this, snaking its way among people and objects and animals, attaching itself first to one thing, then to another. In early America, curious men discussed curious things and displayed curious objects in cabinets of curiosity. Curiosity links a world of ideas with the social worlds in which men, women, and ideas circulated.

Consider this episode in the life of Benjamin Franklin. A young and ambitious Franklin arrived in London in 1724, only to discover that his Philadelphia patron had failed to send letters of introduction. Fortunately, young Ben had other means of introduction: “I had brought over a few curiosities,” he later recalled, “among which the principal was a purse made of the asbestos which purifies by fire. Sir Hans Sloane heard of it, came to see me, and invited me to his house in Bloomsbury Square, where he show’d me all his curiosities, and persuaded me to let him add that to the number, for which he paid me handsomely.”

In this neat little transaction, Franklin turned his curious purse to social connection and to cash, two things he very much needed at the time. He gives us a glimpse too of the gossip among learned men, cabinet keepers, and curiosity seekers; Sir Hans Sloane just happened to have heard of Franklin’s curiosity. How exactly he had heard, Franklin does not say, but someone must have been talking to Sir Hans of the curious young man from the colonies with the collection of curious objects he was willing to show and to sell.

Shared curiosity linked the men of the Enlightenment, in European capitals and the colonies. Curious men and the occasional curious woman exchanged peculiar objects that seemed to defy the categories they had devised to sort out the world: in this case, a purse fire could not destroy. While Franklin and Sir Hans likely had a genteel or learned exchange about the purse, on city streets sometimes more rough-and-tumble seekers turned out to see people with strange features or from strange places displayed as “Great Curiosities.”

In the 1830s, another curious American traveler headed west. In 1834, Richard Henry Dana dropped out of Harvard and worked his way to California as a common sailor. He picked up plenty of “curious and useful information” about his ship, and about California and its residents, and passed it on to readers in his travel narrative, Two Years Before the Mast. In his year working with cowhides on the California coast, Dana met up with some different kinds of curiosities. He remembered one acquaintance who was “considerably over six feet, and of a frame so large that he might have been shown for a curiosity.” The sailor’s feet “were so large,” Dana writes, “that he could not find a pair of shoes in California to fit him, and was obliged to send to Oahu for a pair; and when he got them, he was compelled to wear them down at the heel. He told me once, himself, that he was wrecked in an American brig on the Goodwin Sands, and was sent up to London, to the charge of the American consul, without clothing to his back or shoes to his feet, and was obliged to go about London streets in his stocking feet three or four days, in the month of January, until the consul could have a pair of shoes made for him.“

This story lets curiosity slip off the pages and set its hooks into us. Why would a man send to Oahu for large shoes? Was this barefooted paradise actually a source of shoes for big-footed men? Why the heels on Hawaiian-made shoes? And how often did American sailors wander wintry London streets in their stocking feet? In fact, why was this shoeless man “obliged” to go about the London streets at all? Was it common for the American consul to commission shoes for shipwrecked citizens? Did the consul have a clothing allowance? A shoemaker and a tailor on call?

Dana was curious about the large man; we are curious about Dana’s story. But there is more. Dana reported that a particular Hawaiian friend of his “was very curious about Boston (as they call the United States); asking many questions about the houses, the people, etc., and always wished to have the pictures in books explained to him.” And on the ship back to Boston he encountered one of his old Harvard professors who was very curious about California’s rocks and shells. The professor’s curiosity made the man himself an oddity, an object of curiosity to the sailors. “The Pilgrim’s crew christened Mr. N. ‘Old Curious,’ from his zeal for curiosities, and some of them said that he was crazy, and that his friends let him go about and amuse himself in this way. Why else a rich man (sailors call every man rich who does not work with his hands, and wears a long coat and cravat) should leave a Christian country, and come to such a place as California, to pick up shells and stones, they could not understand.”

For Franklin, Sir Hans, and sailor Dana, curiosity was largely a virtue, a good thing that spurred the inquiring minds of leading men. But as literary historian Barbara M. Benedict reminds us, some people were better at being curious than others. Snooping women got caught up, she writes, in “the seamy obverse of elite inquiry.” A woman’s desire to know flirted with transgression; so did a child’s curiosity to know the world of adults, a worker’s desire for information guarded by a boss, a slave’s interest in doings of his master, and every human desire to know the ways of the gods.

In Benedict’s wonderful account, Curiosity: a Cultural History of Early Modern Inquiry (Chicago, 2001), we learn that even elite male curiosity has a checkered past. Questions that appeared to be disinterested matters of science to men of Franklin’s generation once seemed to ecclesiastical authorities to stem from a dangerous desire to know too much. “Flooded by new and curious men and women,” Benedict writes, “early modern culture characterizes curiosity as cultural ambition: the longing to know more. And this characterization, as both praise and blame, remains with us today.”

This special issue of Common-place takes up the uncommon history of curiosity. Our authors help us notice that men and women who are curious are themselves sometimes turned into curiosities. We are curious about a medical man in Worcester puzzling about the curious behavior of a sleep-walking servant and about a medical missionary displaying portraits of his patients to pique the curiosity and open the purses of would-be donors. We visit the medical museums where men and women curious about their own anatomy gazed on displays of preserved and sometimes grotesque body parts.

Body parts had no say in how they were perceived. But our authors recover stories of men and women who were displayed as curiosities but then turned the curiosity of customers to power or profit. We see explorers in a new world puzzled by strange plants and strange creatures and needing native knowledge to sort the dangerous from the benign in New World flora and fauna. We see merchants in New York, with the help of taste-making ladies, upgrading “Curiosity Shops” by calling them antique stores. We see students curious about a painter of Indians provoking the curiosity of their professor who learns that the artist’s own curiosity about his subjects distinguished his paintings from more pedestrian images that were rendered to meet contemporary tastes and expectations. We encounter a historian caught up in his own curiosity about a portrait of Emily Dickinson. We see a globe maker in rural Vermont whose curiosity about the world beyond the borders of his small state inspires the curiosity of a historian. We watch men and women speculate on the odd things that don’t fit in easy categories. Why did the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin have such a long and strange theatrical afterlife? How did mountain stones come to form the likeness of a human face? What kinds of creatures inhabited ancient America? What race of men inhabit contemporary America?

In the spirit of the old Yiddish proverb–”A man should go on living, if only to satisfy his curiosity”–we welcome readers to join the subjects and authors of this issue in exploring some of its many entangled meanings and consequences.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.2 (January, 2004).

Ann Fabian teaches history and American studies at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Her publications include Card Sharps, Dream Books, and Bucket Shops: Gambling in Nineteenth Century America (Ithaca, 1990) and The Unvarnished Truth (Berkeley, 2000). Fabian is currently working on skull collectors.

Joshua Brown is executive director of the American Social History Project at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. He is the author of Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life, and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley, 2002) and co-author of the CD-ROM Who Built America?: From the Great War of 1914 to the Dawn of the Atomic Age in 1946 (New York, 2000).