Editor’s Introduction

Historians interested in religion and politics in the early American republic have long seen the American Revolution as the catalyst of profound change, with political independence, disestablishment, and nation building stimulating religious growth. Only recently, however, have historians begun to investigate how conceptions of “religion” and “politics” changed in relation to each other in the aftermath of the Revolution, with religion reshaped in the context of mass politics, and politics freighted with an expanding array of religious interests and competing visions of religion-inflected nationhood. As the eight stimulating essays in this issue show, the meanings of religion and politics moved in several directions at once in the early republic. With multiple versions of the relationship between religion and politics proliferating through cheap print, freedom of expression, and geographic expansion, the religiously splintered, relentlessly politicized construction of national identity was anything but consensual.

Each one of these lively essays highlights a different aspect of religion’s relationship to politics.

Kate Engel‘s essay on Jedidiah Morse and the Illuminati scare of the 1790s points to the gap between hysterical reactions to religio-political change on one hand, and historical clarity on the other, about exactly what was changing, and how religion and politics operated to mediate it. If the momentous shift toward secularization identified by theorists of American religion began to take shape in the 1790s, where did that shift begin, and how was it related to what anxious writers like Morse thought was happening?

Kirsten Fischer‘s essay on the world-traveling philosopher John Stewart calls attention to the heterodox religious ideas coursing through the Atlantic world in the midst of revolutionary political change. Unlike Jedidiah Morse, who upheld biblical revelation and ministerial leadership as essential for social order, Stewart espoused a materialistic form of monism based on respect for the vitalism within matter as the key to both egalitarianism and social order. Stewart’s ability to expound on his heretical ideas throughout the early Republic reflected a tolerance for radical new ideas that coexisted with, and perhaps helped inspire, American anxiety about social chaos.

Supporting Fischer’s findings about American hospitality to heterodox ideas, Chris Beneke‘s essay argues that religious coercion in the early republic was relatively minimal. Challenging historians who take the passage of state laws against blasphemy as evidence of the political power evangelicals wielded, Beneke points to the rarity of actual charges of blasphemy, the political freedom Jews and Catholics found, and the general popularity of irreverent and secular thought. While evangelicals developed impressive organizations to promote their religo-political visions, their achievements fell far short of their aspirations.

While Fischer and Beneke highlight the extraordinary political freedom for religious expression that existed in the early republic, Maura Jane Farrelly points to the strong reservations about this freedom expressed by the Roman Catholic Church, and to real tension between religious freedom in the U.S. and nineteenth-century Catholic teaching. While scholars specializing in American Catholic history have long recognized this tension, hyper-vigilance with respect to protestant intolerance has led other scholars to reduce concern about the growing influence of Catholicism in the early republic to simple bigotry.

Eric Schlereth‘s essay on Robert Dale Owen further complicates historical understanding of the relationship between religion and politics in the early republic, and Catholicism’s role in that relationship. Focusing on Robert Dale Owen, a political leader from Indiana with a colorful background in religious infidelity, Schlereth calls attention to the power Owen achieved among Democrats, the political party strongly supported by Catholics. With puritanical Whigs opposed to both Catholics and free thinkers, and Democrats opposed to Whigs, religious combinations operating within party machines help explain Owen’s success.

Linford Fisher‘s essay on “foreign” missions reveals another combination of religious forces with far-reaching political implication. Rooted in European missionary societies active during the colonial period, American missionary societies became bases of America’s global outreach in the early republic. Once on the periphery of European empires, America became an imperial center, with missionaries in foreign fields exporting religio-political theories developed in America along with programs for individual salvation.

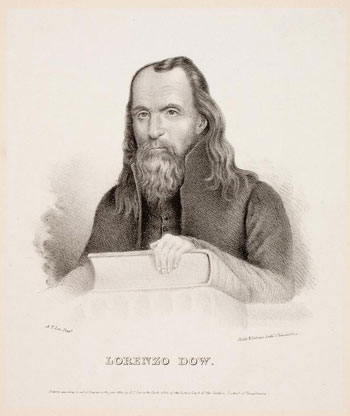

Seth Perry‘s essay on religious performance suggests how fraught with irony such evangelical efforts could be. Focusing on the life of “crazy” Lorenzo Dow, Perry shows how successful Dow became in parading his own apostolic poverty as a critique of the wealth and political authority of religious elites. After amassing considerable property as a result of his success as a religious performer, Dow entertained the idea of establishing a religio-political empire of his own.

Looking into much darker forms of religious interaction with politics, Edward Blum‘s essay on Satan shows how importantly religious hatred and fear figured in antebellum political discourse. Casting political opponents in league with Satan, both explicitly and by innuendo, not only sharpened differences to the point of denying any possible resolution, but also conjured visions of imminent chaos engulfing all. These appeals to Satan, Blum argues, gave rein to hatred and disorder as they paved the way to war.

Each one of these lively essays highlights a different aspect of religion’s relationship to politics. Their diversity illustrates the different directions this relationship took in the early republic, and the historical understanding to be gained by resisting simple ideas about how that relationship worked. No less important, this splendid collection reveals the unstable boundary between religion and politics in the early republic, and the porous character of that boundary as Americans vied with each other to define the nation.

This article originally appeared in issue 15.3 (Spring, 2015).

Amanda Porterfield is Robert A. Spivey Professor of Religion and professor of history at Florida State University. Her most recent book is Conceived in Doubt: Religion and Politics in the Early American Nation (2012).