Several of Whitman’s great contemporaries, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Herman Melville, were, like Whitman, moralists with strong anti-moralistic streaks. In “Self-Reliance,” Emerson praises the “nonchalance of boys who are sure of a dinner, and would disdain as much as a lord to do or say aught to conciliate one.” He claims that “society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of every one of its members.” In response, he vows to follow his own god-like genius and conscience. It will not be immoral, he claims, because he will be obeying his own higher law, even if it appears like sin to others:

[M]y friend suggested, – “But these impulses may be from below, not from above.” I replied, “They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil’s child, I will live then from the Devil.” No law can be sacred to me but that of my nature.

Thoreau, too, claims freedom from conventional morality, and links freedom to youth, gladness, and nature. As Whitman says admiringly, “One thing about Thoreau keeps him very near to me: I refer to his lawlessness—his going his own absolute road let hell blaze all it chooses.” Thoreau writes in his notebook:

Methinks that these prosers, with their saws and their laws, do not know how glad a man can be. What wisdom, what warning, can prevail against gladness? There is no law so strong which a little gladness may not transgress. I have a room all to myself; it is nature. It is a place beyond the jurisdiction of human governments. Pile up your books, the records of sadness, your saws and your laws. Nature is glad outside, and her merry worms within will ere long topple them down. There is a prairie beyond your law. Nature is a prairie for outlaws.

Thoreau sometimes feels that he owes his success to his vices, and if he repents of anything, it is his good behavior. The so-called wisdom of elders is mainly an impediment: “I have lived some thirty years on this planet,” he writes, “and I have yet to hear the first syllable of valuable or even earnest advice from my seniors.”

Like Emerson, Thoreau emphasizes that the self-reliant man must be prepared to spurn even familial duties. Emerson says, “I shun father and mother and wife and brother when my genius calls me.” Thoreau adds friends to the equation: “If you are ready to leave father and mother, and brother and sister, and wife and child and friends, and never see them again . . . then you are ready for a walk.” To walk is to learn “sauntering,” the American art of going on the road or into the woods to escape from oppressive society. Thoreau needs to spend at least four hours a day sauntering through the woods, and he marvels that mechanics and shopkeepers who have to sit at work all day long do not commit suicide.

For Melville, the equivalent of sauntering is setting out to sea. As Ishmael says in Moby Dick, “I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.” For Emerson and Thoreau, escaping convention is at its root a solitary venture, much as they prize their walks with each other. For Melville, part of sailing’s allure is camaraderie and the alternative society furnished by the shipmates (or, in Typee, a tribal society on “barbarous coasts”), but in Moby Dick, tragically, that alternative society falls prey to Captain Ahab’s tyrannical mania, and Ishmael ends up as he started, alone. Melville may have valued friendship more than Emerson and Thoreau, but he was no more sanguine about its powers of salvation. Ishmael and Queequeg cling together for a time, but then Queequeg vanishes into the abyss.

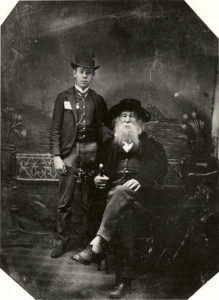

Whitman values his solitude, but when he sets out on the open road or strolls the city’s streets, he often wants a friend or lover to hold his hand. His rebelliousness stems from individualism, but also from passion. Because he partially suppresses the eroticism in his Calamus poems, the theme of antinomian love appears more powerfully in another sequence from the late 1850s: the Enfans d’Adam poems, which announce their theme as heterosexual love, rather than love among men. In “O furious! O confine me not,” for example, he longs to “drink the mystic deliria:” to find a “new unthought-of nonchalance;” to have the “gag removed” from his mouth, and to “court destruction,” if need be, for “one brief hour of madness and joy.”

The three poems that follow “O furious! O confine me not” in Enfans d’Adam are some of Whitman’s most powerful love poems. All three seem directed at men and could have been placed in the Calamus section, had he chosen to more fully eroticize it. “You and I—what the earth is, we are” is particularly reminiscent of “We two boys together clinging.” Whitman uses a long list to characterize the lovers, beginning 19 of the 21 lines with “We.” As in “We two boys,” the freedom of the lovers is linked closely to the freedom of nature: he compares them to plants, rocks, oaks, fishes, blossoms, suns, and clouds. Again, he uses aggressive images: predatory hawks soaring and four-footed animals prowling and springing on prey. The lovers are equal, even identical; at no point does he differentiate them (which, given Whitman’s usual patterns of language, strongly suggests that they are both male). In many of the images, the lovers are parallel—oaks growing side by side, fishes swimming in the sea together—but in one crucial line they mingle: “We are seas mingling—we are two of those cheerful waves, rolling over each other, and interwetting each other.” As in “We two boys,” love achieves liberation by spurning society; as he writes in the triumphant last line: “We have voided all but freedom, and all but our own joy.”