“Human Fire Fierce Glowing”

Comments on the American Revolution Reborn

I’d like to open briefly with some remarks about themes, and then highlight something important that has been missing from the rest of our discussions.

Before all else, it is absolutely critical to do what so many involved in this conference are trying and proposing to do—that is, situate the American Revolution in its transnational and Atlantic contexts. This is crucial to rethinking the nationalist origin myth. It is equally critical to offer a new, archive-based history of the revolution “from below” and to concentrate on a mass of experience that would include Native Americans, African Americans, workers, and women. A fully realized new narrative will depend on facing and accomplishing these tasks.

The new work in turn will face two dilemmas. First, if Michael McDonnell and others are right in saying that roughly sixty percent of the population in the American colonies were “disaffected” in the run-up to the revolution, and even after it broke out, and if the remaining forty percent were more or less evenly divided between Loyalists to Britain and American patriots, this set of facts makes the victory of the patriot movement more improbable and, in the end, even more spectacular. This in turn will prompt a new round of no doubt celebratory studies about how the patriots did it, likely confirming the dictum offered by C.L.R. James that most history is made by small, highly organized groups of people. How did such a group come to create and use the nation-state as a modality of power? Multiple histories from below will collide, conflict, and occasionally overlap. How a smaller-than-imagined patriot movement managed to mobilize the labor to fight and win the war may emerge as the pivotal issue.

Second, if a new narrative of the American Revolution “from below” should arise, we know from past experience that it will be completely unacceptable to the ruling class of the country. We should recall the National History Standards debate in the early and mid-1990s, when a team of historians, led by Gary Nash, proposed to integrate the new social history of the previous generation into the body of knowledge every student in the United States should possess, only to have its proposed revision voted down 99-1 in the U.S. Senate because it was “insufficiently patriotic.” This matter also deserves serious discussion here and hereafter.

The “something missing” in the conference is big, elusive, and difficult to express. I’d call it the profound historic power of the revolutionary idea—the notion that human beings can organize themselves collectively, in a movement, to change the very course of history. This is a modern idea, and a powerful one. It is so central to modern consciousness that, perhaps, we take it for granted. We should not. Within the revolutionary idea lies another, a concept much used, and abused, by historians these days. I refer to “agency.” Who are the historical agents? The American Revolution helped to form the idea of conscious, willed, systemic, historic change—and thereby the very notion of agency itself.

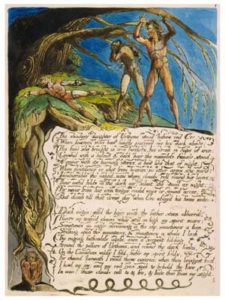

In preparing these remarks, I asked myself, how can I best sum up the power of the revolutionary idea? I tried to find examples of writers who understood and expressed it. The best example I could come up with was a contemporary of the American Revolution, the great English poet and artist William Blake. I refer to his visionary poem, America, A Prophecy, and to several engravings he made around the same time.

In case you are wondering, yes, I really am going to hold all of us historians to the standard of William Blake. May God help us. Here we go.

Blake saw the American Revolution as … revolutionary. His poem opens with a symbol of revolution, Red Orc, pinioned to the ground, his arms and legs bound by “tenfold chains.” He breaks free of his manacles. The “age of revolution” begins.

Solemn heave the Atlantic waves between the gloomy nations,

Swelling, belching from its deeps red clouds & raging Fires!

Albion is sick. America faints! enrag’d the Zenith grew.

As human blood shooting its veins all round the orbed heaven

Red rose the clouds from the Atlantic in vast wheels of blood

And in the red clouds rose a Wonder o’er the Atlantic sea;

Intense! naked! a Human fire fierce glowing, as the wedge

Of iron heated in the furnace; his terrible limbs were fire

With myriads of cloudy terrors banners dark & towers

Surrounded; heat but not light went thro’ the murky atmosphere

The King of England looking westward trembles at the vision

Blake wrote the poem in 1793, a profoundly revolutionary moment, in England, Ireland, France, and St. Domingue.

The King of England sends his war angels against Red Orc, who, by the way, is no gentleman. He is rather a “Blasphemous Demon, Antichrist, hater of Dignities” and a “Lover of wild rebellion, and transgresser of Gods Law.” Orc is violent, murderous, uncontrollable, unpredictable, and apocalyptic, an apt symbol for a truly revolutionary age.

The King then unleashes demons to spread pestilence among the rebellious Americans. But “the red flames of Orc” defeat him as the Americans declare their rebellion: “no more I follow, no more obedience pay.” The patriots unite in solidarity, what Blake calls “the fierce rushing of th’inhabitants together.” Sailors take direct action against property, tomahawking casks of tea and dumping it into Boston Harbor; Tom Paine “casts his pen upon the earth” and writes Common Sense.

Red Orc reaches across the Atlantic, for soon “France reciev’d the Demons light.” “Stiff shudderings shook the heav’nly thrones! France Spain & Italy … And so the Princes fade from earth, scarce seen by souls of men.” A more hopeful future, republican and revolutionary, emerged from the purifying fire. Of America, Blake concludes, “But tho’ obscur’d, this is the form of the Angelic land.” This is Blake’s history, his prophecy.

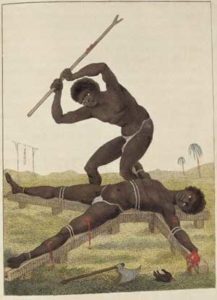

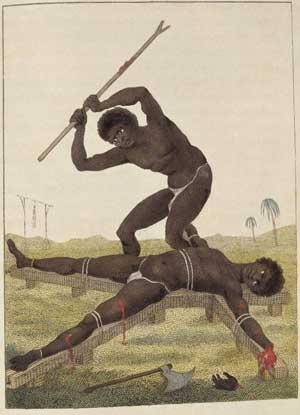

Blake paid close attention to freedom struggles around the Atlantic, especially when engraving eighteen images for John Gabriel Stedman’s Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Suriname (1796). He based his Red Orc on an African man named Neptune, who was executed in the storied year 1776 in Suriname for killing a white overseer. Like Neptune, Orc was pinioned to the ground. Blake called him “the image of God who dwells in darkness of Africa.” Blake thus used a tortured African rebel to express his own hopes of freedom in the age of revolution.

Let me be clear: I am not saying that Blake is typical of anyone in his generation; I am not saying he studied or even knew a great deal about the American Revolution. He probably did not understand the conservative goals that some of the “revolutionaries” fought for. What I am saying is that he intuited something big and important, as a great poet ought to do! This circulation of “the demon’s light”—the revolutionary idea and its new possibility—is a key to the American Revolution, as Blake well understood.

There have been many critiques and deconstructions of “revolution” as a concept in recent years. Some of this is valuable, but some of it is pure cynicism, an expression of the degradation of politics, in the United States and around the world, in this era of Reagan and Thatcher. There is something important to be saved in the notion of revolution, as Blake teaches us. This brings us back to the concept of agency, which, we usually forget, has its own history. The American Revolution helped to establish the very possibility of collective, world-changing agency. Tom Paine understood this. He wrote in Common Sense: “Kings are not taken away by miracles, neither are changes in governments brought about by any other means than such as are common and human; and such as we are now using.”

Following Blake and Paine, I would hope that the new histories of the American Revolution would include more “Human fire fierce glowing.” The universalistic claims of the revolutionaries are historically important, even though many who uttered them in 1776 were in full retreat by the time Blake wrote his praise-song to revolution in 1793. Counter-revolutionary fears should not blind us to the potent idea they had helped to unleash a few years earlier.

This article originally appeared in issue 14.3 (Spring, 2014).

Marcus Rediker is Distinguished Professor of Atlantic History at the University of Pittsburgh. He is author of numerous prize-winning books, including (with Peter Linebaugh) The Many Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic (2013), from which this essay draws, and most recently, The Amistad Rebellion: An Atlantic Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom (2012).