On Monday morning, July 1, 1776, just as delegates to the Continental Congress were assembling in the East Wing of the Pennsylvania State House to resume debate on declaring independence, a currier handed John Adams a letter from Samuel Chase. The Maryland Convention had suddenly reversed its position, Chase informed Adams. Three weeks earlier, in response to Richard Henry Lee’s momentous resolution in favor of independence, the Maryland delegation had stormed out. Then Chase and others sent the matter back to the county conventions, and at least four of these instructed their delegates to the Maryland Convention to instruct its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote in favor of Lee’s resolution. In an emergency session on Friday evening, June 28, the Maryland Convention finally conceded to the dictates of the county conventions. “See the glorious effects of county instructions,” Chase now boasted to Adams. “Our people have fire if not smothered.”

Elsewhere, local conventions were instructing their delegates to higher bodies to take the big leap—towns to county conventions, counties to provincial congresses, and these to the Continental Congress. Historian Pauline Maier has cataloged ninety of these “other” declarations of independence. Lee’s congressional motion for independence, in fact, stemmed from the Virginia Convention’s instructions to its delegates to the Continental Congress to introduce just such a measure.

Fifty-seven of the lower bodies on Maier’s list were Massachusetts townships. This is no mere coincidence, for local town meetings had been telling their delegates to the General Court exactly how to behave throughout the late colonial period. For congregational New Englanders, who took the notion of popular sovereignty at face value, instructions constituted the perfect link between local and provincial government. If government existed for the good of the people, it stood to reason that the people themselves were entitled to make the decisions. There should be no intermediaries. Just as ministers should not stand between a people and their God, so should political representatives merely facilitate the popular will, not define it. Because of the corporate nature of their communities, furthermore, Massachusetts citizens assumed that the will of the people could be readily determined in their town meetings and then set to paper in the form of explicit instructions.

Take the town of Worcester, the “shire town” or (seat of government) of Worcester County. In 1766, the town meeting instructed Ephraim Doolittle, its representative to the General Court, to “use the whole of your influence and endeavor” to put an end to plural officeholding, construct a “convenient house” in which spectators could observe the proceedings of the General Court, revise the fee schedule by which public officials lined their pockets, repeal all excise taxes, shut down the publicly funded Latin grammar schools (of no use to ordinary farmers), and pass a law prohibiting all bribery and corruption. The townsmen concluded on a stern note: “That you give diligent attendance at every session of the General Court of the province this present year, and adhere to these our instructions, and the spirit of them, as you regard our friendship, and would avoid our just resentment.”

The following year, the Worcester town meeting repeated most of these items, with one key addition.

That you use your influence to obtain a law to put an end to that unchristian and impolitic practice of making slaves of the human species in this province; and that you give your vote for none to serve in his majesty’s Council, who, you may have reason to think, will use their influence against such a law.

Instructions had revolutionary implications, in both form and content. Once the door was opened to popular control of government, who knew how far the people would go? Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Hutchinson recognized the danger, and it alarmed him. In 1766, recently ruffled by the mob demolition of his house, he argued that instructions threatened the roots of orderly government by prohibiting calm deliberation. “To hold each representative to vote according to the opinion of his town…contradicts the very idea of a parliament the members whereof are supposed to debate and argue in order to convince and be convinced.”

Hutchinson’s fears proved well founded, for in the decade to follow, American patriots used instructions to push their agendas on deliberative bodies. Witness the heated Instruction War in Worcester, May 16-August 24, 1774.

At the town meeting on May 16, citizens selected Joshua Bigelow to represent them in the General Court and appointed a committee to prepare a draft of his instructions. Six of the seven committee members belonged to the town’s radical caucus, the American Political Society (APS), and these men utilized the genre of “instructions” to hurl invectives against British imperial policies as liberally as they would in a political broadside. They also minced no words in demanding that Bigelow (also an APS member) carry the good fight on their behalf. “We, in the most solemn manner, direct you, that whatever measures Great Britain may take to distress us, you be not in the least intimidated…but to the utmost of your power resist the most distant approaches of slavery.” They placed Bigelow under “the streckest injunction” not to approve compensation for the tea dumped into the Boston harbor; they directed him to conclude the impeachment proceedings against Chief Justice Oliver for accepting a salary from the Crown; they “earnestly require[d]” him to use his “utmost endeavors” to convene “a general Congress” of the committees of correspondence from throughout the colonies. (This convention, four months later, would evolve into the Continental Congress).

Although the town’s Tory opposition vehemently opposed this political diatribe, the instructions carried the day, unaltered.

But opponents did not concede. They gathered forty-three signatures on a petition that called for a special town meeting to reassess the previous vote, and according to law, the selectmen were required to honor this petition. So on June 20 both sides mustered their forces for a showdown.

Although local Tories had gathered every “friend of government” they could, there were simply not enough of them in Worcester. Once more the radicals prevailed, but this time, although outvoted, the Tories drafted a dissent, which they published in the Boston newspapers.

We behold so many whom we used to esteem sober, peaceable men, so far deceived, deluded and led astray, by the artful, crafty and insidious practices of some evil-minded and ill-disposed persons, who, under the disguise of patriotism, and falsely styling themselves the friends of liberty, some of them neglecting their own proper business and occupation, in which they ought to be employed for the support of their families, spending their time in discoursing of matters they do not understand,…intend to reduce all things to a state of tumult, discord and confusion…

These and all such enormities, we detest and abhor, and the authors of them we esteem enemies to our King and Country, violators of all law and civil liberty, the malevolent disturbers of the peace of society, subverters of the established constitution, and enemies of mankind.

Fifty-two supporters of the British Crown—the “Protestors,” as they were called—affixed their names to these vitriolic words, and in a town with fewer than 250 eligible voters, this constituted a sizable minority. The community of Worcester was at war with itself.

But that war came to an abrupt end when the citizens of Worcester learned that Parliament had just passed the most abusive of all its punitive measures: the Massachusetts Government Act, which unilaterally revoked key provisions of the colony’s constitution, the 1691 charter. Town meetings, the basis of local self-government, were outlawed; they could only convene at the pleasure of the Crown-appointed governor, who had to approve all agenda items. Members of the powerful Council, formerly elected, would henceforth be appointed by the King. All local officials, such as sheriffs and judges, would no longer be subject to the approval of elected representatives, while even jurors would be selected by Crown-appointed officials, not by the people themselves.

In Worcester, the new Government Act altered the political landscape beyond recognition. Before, Tories could present a reasoned (albeit controversial) argument for remaining true to imperial authority; afterwards, the Tory stance was entirely discredited. There was no way to argue that citizens could benefit by having their political enfranchisement yanked away.

Activists from the APS seized the moment to squash the local Tories, once and for all. They forced the fifty-two Protestors to “beg forgiveness” in a formal recantation, but that alone would not suffice. In a town meeting on August 24, they forced each of the Protestors, one at a time, to strike a line through his signature at the bottom of the Protest, which the town clerk, Clark Chandler—son of the town’s most prominent citizen over the past decades, John Chandler—had entered in the official journal.

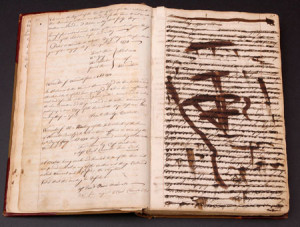

Then, unhappy with even the appearance of dissent, the patriots ordered the clerk to “obliterate, erase, or otherwise deface” the Protest from the record. Left with no other option, Chandler inked his pen and drew it across the Protest, line by line, in full public view (fig. 1).

But even that would not suffice. A few words could still be deciphered in the record book, the patriots claimed, so they made him do it again—this time with continuous loops of tight spirals that rendered the Protest unintelligible.

Certainly that should have ended the matter, but it didn’t. We do not know exactly what triggered the last dramatic humiliation, but we do know that in full view of the town meeting, Worcester’s town clerk was forced to dip his own fingers in a well of ink and drag them over the first page of the Protest. The short, irregular changes of direction in the defacements on this document suggest that Chandler’s hand was forced.

Worcester’s Instruction War was over, and two weeks later, on September 6, patriots from around the county gathered in the shire town to close the courts. Mustering in thirty-seven units from their respective towns, 4,622 militiamen lined both sides of main street and forced some twenty-five court officials to walk the gauntlet, reciting their recantations at least thirty times apiece, hats in hand. With this dramatic humiliation, all British authority vanished from both the town and county of Worcester, never to return.

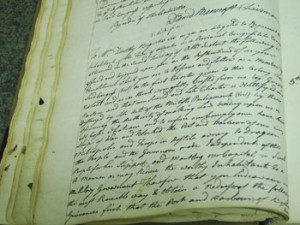

That left local citizens without any legitimate government. So on October 4, 1774, the town of Worcester issued a truly historic instruction to its representative to the forthcoming Provincial Congress, Timothy Bigelow, Joshua Bigelow’s cousin.

You are to consider the people of this province absolved, on their part, from the obligation…contained [in the 1691 Massachusetts charter], and to all intents and purposes reduced to a state of nature; and you are to exert yourself in devising ways and means to raise from the dissolution of the old constitution, as from the ashes of the Phenix, a new form, wherein all officers shall be dependent on the suffrages of the people, whatever unfavorable constructions our enemies may put upon such procedure.

Exactly twenty-one months before the Continental Congress would approve its own Declaration of Independence, the citizens of the town of Worcester had decided it was time to form a new and independent government, no matter what anybody else might say (figs. 2 and 3).

But despite the efforts of Timothy Bigelow, in obedience to the instructions of the Worcester town meeting, a “new form” of government did not rise in a set piece “from the ashes of the Phenix.” The Provincial Congress, which effectively ascended to power in the wake of the old order’s demise, refrained from proclaiming its own authority, for fear of alienating other colonies. It “recommended” various measures, including the payment of taxes to its own treasurer, but it shied from calling them “laws.”

In the summer of 1775, with the approval of the Continental Congress, the Provincial Congress assumed authority according to the 1691 charter, absent the royal governor, but this did not satisfy Massachusetts radicals. They wanted their “new form,” and they wanted to draft it themselves. When the state legislature submitted a constitution for approval by the people in 1778, it was overwhelmingly rejected, in part because of an absence of any declaration of rights but also because the majority of citizens wanted a say in setting up their own government.

Finally, in a statewide referendum held in the spring of 1779, Massachusetts citizens voted overwhelmingly to hold a special convention with the express and sole aim of drafting a new constitution, which would of course be submitted to the people for ratification. Through the summer, towns chose delegates and sent them forth, often with specific instructions. As citizens of Bellingham told Noah Alden, “We your constituents claim it as our inherent right at all times to instruct those that represent us, but more necessary on such an important object which not only so nearly concerns ourselves but our posterity.”

Virtually all the instructions opened by insisting on the need for a bill or declaration of rights, often delineating the specific guarantees that must be written into the new constitution. The list compiled by the people of Pittsfield closely foreshadowed the national Bill of Rights, which would be adopted a dozen years later, but it also included one critical injunction that never found its way into the famous document we all treasure. “[A]s all men by nature are free, and have no dominion one over another, …that no man can be deprived of liberty, and subjected to perpetual bondage and servitude, unless he has forfeited his liberty as a malefactor.”

Typically, the instructions insisted that people have the ultimate say in their government. Most called for annual elections, and beyond that, although ideas differed, towns promoted various mechanisms intended to secure the authority of the people: a prohibition against executive vetoes, an insistence that all taxes originate in the lower house of the legislature, and in one case, a unicameral legislature, so the voice of the people would remain unchecked by any other authority.

Citizens of Sandisfield were very specific in their list of instructions, which, in total (over 2,500 words), might be mistaken for a first draft of the new constitution, right down to the residency qualifications for lieutenant governor (one year), the time for annual elections (April), the precise number of senators (twenty) and probate judges (twenty-four), and so on. The people from Gorham, on the other hand, concluded their instructions with a modest plea for minimalism. “The sense of Gorham relative to a mode of government the more simple, the less danger of the loss of Liberty and the most tending to happiness with the least expence.”

Several town meetings told their delegates that drafts of the Constitution should be printed and circulated to every town, so that the people might ponder its provisions and suggest amendments. Some made it clear they expected the convention to meet a second time, so delegates could incorporate the proposed amendments into a revised version. Only after the people at the township level had provided their input would the Constitution be resubmitted for final ratification.

This almost happened—but not quite. On March 2, 1780, the Convention ordered 1,800 copies of its completed document to be dispatched to the towns, which were at liberty to propose amendments. Each article had to garner approval from two-thirds of the voting population; if not, the controversial issue would be returned to the Convention, which would incorporate the relevant amendments and rewrite the article. There would be no second referendum, however, so the people themselves would have no further say in the matter.

Overall, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 was well received, but certain articles did arouse opposition, most notably Article III of the Declaration of Rights, which required each community to support public worship. Although many towns proposed amendments related to this and several other matters, the suggestions were all over the map. Richmond, for instance, insisted that all militiamen, not just those over the age of twenty-one, have a voice in choosing their captains, that judges be appointed annually rather than serve indefinitely, and that property qualifications for the offices of governor and lieutenant governor be reduced and capped. Meanwhile, those very particular citizens of Sandisfield noted that “the word Council ought to be erased and the word Senate inserted” in Chapter 1, Section 2, Article III; they also renewed their objection to the governor’s veto power and advocated closer scrutiny by the legislature over the fee table for local officials. When the Convention met again in June, it categorically refused to deal with these diverse amendment proposals. Instead, it declared on the basis of partial results (many towns had failed to report numerical returns) that the two-thirds threshold had been met for every article and the entire Constitution would take effect, without alteration.

Still, for those towns that had initially issued instructions to their delegates, the people had had some say in the matter, beyond choosing delegates and granting their assent in the end. Furthermore, according to the document itself, they could always have their say, as Article XIX of the Declaration of Rights laid out clearly. “The people have a right…to give instructions to their representatives.”

The Federal Constitution of 1787, on the other hand, included no guarantee for the right of issuing instructions, and this was hardly an accident. Instructions implied that the ultimate responsibility for decision making lay with the people, but as Madison argued so forcefully in Federalist no. 10, the judgment of representatives, with their “enlightened views and virtuous sentiments,” was likely “superior” to that of the people, with all their “local prejudices.” If election districts were large enough, Madison predicted, the people in any locality would not be able to come together as a body and bind their representative to specific actions. Large districts and the absence of instructions effectively precluded a democratic government, in which the people themselves can dictate their will, in favor of a republican government, in which wiser men rule.

Madison and the framers got their large election districts, which did indeed render instructions to congressional representatives unfeasible. Ironically, however, the notion of instructions staged a revival in the new federal Senate, allegedly the province of the most enlightened leaders. Since senators were elected by state legislatures, some of these bodies assumed the authority to dictate terms to the men whom they had chosen to represent their states at the national level. Although this was hardly the intention of the framers, who had tried to remove the Senate from the “influence” of “factions” (to use the parlance of the times), several state legislatures tried to bind United States Senators with instructions on very specific matters. The practice continued intermittently until 1913, when the Seventeenth Amendment transferred the choice of Senators from the state legislatures to the people.

Today, although there is no formal provision for issuing instructions at the federal level, neither are instructions specifically prohibited, and at least in Massachusetts, that cradle of local democracy, the right of instructions is still legally guaranteed. The problem now lies with the infrastructure. Back in revolutionary times, there was a direct and functional chain of command between the people and the highest level of government officials: citizens at their town meetings chose and instructed representatives to their provincial (and later state) governments, and these in turn chose and instructed representatives to the federal Congress. In the name of democracy, this chain has been broken, with people electing their federal representatives directly. But they do so separately, from the privacy of voting booths, and they have only an indirect say in the matter for the next two, four, or six years, when the next election cycle comes around.

The vacuum left by the absence of instructions has been filled in two ways—most obviously by lobbyists, who exert far more influence on the people’s representatives than the framers dared to imagine, but also by ballot referendums, those hybrids of democracy and mass-market capitalism, in which public opinion and special-interest money combine in an unholy alliance to legislate on matters large and small. Only by reinventing some variant of that revolutionary chain-of-command, starting at the “town meeting” level, might ordinary citizens place themselves as prominently in the mix of politics as they did at the nation’s founding.

Further Readings:

To my knowledge, there is no comprehensive study of community-based instructions during the revolutionary era. Pauline Maier, in American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (New York, 1998) lists and discusses many (but not all) of the instructions from the spring of 1776, which pushed Congress to declare independence. Most of these primary sources are reprinted in Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Fourth Series: A Documentary History of the English Colonies in North America from the King’s Message to Parliament of March 7, 1774, to the Declaration of Independence by the United States (New York, 1972; first published 1833-1846). Transcriptions of the instructions from the Town Meeting of Worcester can all be found in Franklin P. Rice, ed., Worcester Town Records from 1753 to 1783 (Worcester, Mass., 1882), but this book is difficult to locate; it might be easier to access the original records at the city clerk’s office. Similarly, instructions from numerous other town meetings throughout Massachusetts can be accessed by going directly to the respective town offices. About a dozen sets of instructions from various towns are reprinted in L. Kinvin Wroth, ed., Province in Rebellion: A Documentary History of the Founding of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 1774-1775 (Cambridge, Mass., 1975). For instructions leading up to the Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780, see Oscar and Mary Handlin, eds., The Popular Sources of Political Authority: Documents on the Massachusetts Constitution of 1789 (Cambridge, Mass., 1966).

Secondary sources: For a brief discussion of instructions in the revolutionary era, see J. R. Pole, Political Representation in England and the Origins of the American Republic (New York, 1966): 72-75, 80, 94-95, 161-165, 211-214, 229-240, 441, 541-542. For a narrative of the Massachusetts Rebellion of 1774, in which instructions played a crucial role, see Ray Raphael, The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (New York, 2002). For instructions from state legislatures to the United States Senate during and beyond the early republic, see C. Edward Skeen, “An Uncertain ‘Right’: State Legislatures and the Doctrine of Instruction,” Mid-America: An Historical Review 73:1 (January 1991): 29-47.

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Writer/historian Ray Raphael, author of fourteen books, turned his attention to the American Revolution in the mid-1990s. His books include A People’s History of the American Revolution (2001; 2002), The First American Revolution: Before Lexington and Concord (2002), and Founding Myths: Stories that Hide our Patriotic Past (2004). His latest and most challenging book—a sweeping narrative of the founding era based on the lives of seven representative figures (both George Washington and Private Joseph Plumb Martin, for instance)—will be out this coming spring.