Is There a Historian in the House?: History, reality, and Colonial House

“If you knew what you were getting into, would you do it again?” That question was recently posed to me by one of the producers of the PBS series Colonial House, after I had just completed more than a year as a lead consultant for the show. A follow-up to such popular shows as Frontier House and Manor House, the series is an effort to blend reality television with history. A group of modern day “colonists” spent four months of 2003 experiencing the life of settlers in 1628 Maine. The colonists undertook a crash course in seventeenth-century living, were provided with historically accurate food, clothing, shelter, and other necessities, and had to carve out a colony on the harsh and unforgiving shores of a new land. They were filmed regularly, and the result was an eight-hour series that premiered May 17.

Some historians might view the muck of a recreated 1628 village as a long way from the ivory tower—and a still longer way from the real 1628—and thus steer well clear of such a project. I must admit I had a few doubts when PBS first approached me. After all, Frontier House had occasionally threatened to turn into Survivor meets Little House on the Prairie. Still, I was struck by the incredible power of this popular series. I was amazed by my young daughters’ fascination with the show—and their willingness to watch it again and again. Despite its flaws, people talked about Frontier House—including many folks who never showed much interest in history before.

So, it seemed worth the risk, as Colonial House was a rare opportunity to present early American history to a large audience. Most history on television focuses on the recent past, where photographs, film clips, and other visual materials are readily available. All too often, the History Channel becomes the World War II Channel. Finally, early America was getting the attention it deserved and I could be a part of it. The alternative was to stay on the sidelines, and my family was already heartily sick of hearing my complaints about bad history on television.

Occasionally I did question my decision to get involved. My responsibilities on the show were wide ranging and often time consuming. Drawing on court records, legal codes, letters, account books, and many other primary sources from England and America, I put together the historical background for the colony including its charter, the governor’s commission, even the historical backgrounds for individual colonists. The production team studied these materials and also placed the documents in the hands of our colonists to help order their society. I helped train the “settlers,” and was one of the on-camera experts who assessed their relative success in establishing a community and making a profit for their sponsoring company in England. I weighed in on numerous historical questions ranging from, What was a beaver pelt worth in 1628? to Would the colonists have exported blueberries?

I quickly realized that much more so than my other public-history projects, Colonial House had to weave historical accuracy with modern-day reality. Unlike a museum exhibit, talking-head documentaries, or even Plimoth Plantation where the staff goes home at night, these twenty-first-century colonists were really living living history, and bringing their modern worldviews and expectations with them. The series also had to pay close attention to what the production team called “the televisual moment”: a compelling, brief, and visually interesting scene that told a story. And not least, we had to work within the confines of close deadlines and tight budgets. Thus Colonial House was a constant balancing act between the ideal and the practical, between the televisual story, the sound bite, and the historical record. Clearly, this leads to some unique problems and opportunities for the historian.

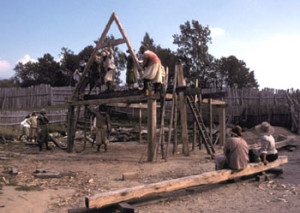

Thanks to the talented staff of Plimoth Plantation, most aspects of the material world of 1628 could be reproduced. However, there were practical limits to the project. For example, a real colony in 1628 would most likely have been an armed camp, complete with a night watch, a hastily constructed palisade, and a military leader such as John Smith or Miles Standish. Unfortunately, safety precautions and modern-day laws preempted any efforts to arm our colonists with clumsy matchlock muskets, leading to the wholesale elimination of an important aspect of a colony’s first months. It is probably just as well, or we might have accidentally lost a colonist or two. Still, a little martial drill with some unloaded firearms and the construction of a section of palisade might have at least given the flavor of this experience.

Furs, fish, and lumber were even more plentiful than weapons in 1628 Maine, so planters had lots of goods to export. Our settlers faced a different reality—a twenty-first century world of scarcity. Their colony was a blueberry barren, with no hardwood, and little in the way of game or fur bearers. The Maine fishing banks are now so depleted that many fishermen are going bankrupt, so how could our colonists succeed?

Despite these material constraints, it was much more difficult to recreate the mental world of 1628. The long history of mistreatment of Native peoples made it tough for our colonists and their modern-day Native American visitors to portray first encounters and the subsequent fur trade. Likewise, how do you deal with the complexities of slavery and race relations in 1628 with the hindsight of 2003? How can you enforce seventeenth-century religion and morality on people with a diverse, and often secular modern worldview? Especially when there is no available means of punishment other than public humiliation—something that only works if the offender and the public agree that the transgression merits shame. Such issues meant that the twenty-first century kept rearing its ugly head into the series.

So, was Colonial House perfect? Reality never is, and reality television is no different. I had an excellent relationship with the production team, professionals who were genuinely concerned with historical accuracy. However, if I had been the producer rather than a consultant, I would have changed a number of things. First, the show needed far more historical explanation right up front to set the stage and explain the limitations of the series. For example, I would have more clearly laid out how the show portrayed race in 1628. Some viewers who knew that Africans had not migrated to northern New England this early were puzzled to see apparent free blacks in our colony. No, there were no Africans or Chinese (or Italians for that matter) in 1628 New England, but Americans with these and other proud heritages are an important part of the 2003 effort to recreate a founding moment of our American nation.

It is difficult to explain complex ideas like joint stock companies and seventeenth-century Protestantism in televised sound bites, but a stronger effort was needed. The differences between Puritanism and Anglicanism—differences for which people in the era Colonial House portrayed fought and died—were never really discussed on screen. I fear many viewers will equate the governor’s enforcement of the Sabbath with Puritanism, without realizing that this was the norm in the Protestant world of 1628, and that our colony was actually loyal to the Church of England.

would have avoided the twenty-first century as much as possible. The narrator acknowledges that people in 1628 did not celebrate birthdays, so why include the birthday party and other clearly modern moments? When I did enter 2003, it would have been to discuss the historical research that shaped the colony. Plimoth Planation deserves far more credit than it got for the hundreds of hours its staff put in, making sure the architecture and material culture were as accurate as possible. Perhaps it is the deluded historian in me, but I think people would have been fascinated by how the colony was put together. I even suggested to PBS that an episode of Novacould be dedicated to Colonial House as experimental archaeology. PBS passed on the idea, though it may still occur informally. Plimoth Plantation staff have already begun asking the former colonists why they chose to carry out activities in certain ways. Thankfully, the show frequently cites its companion Website, where viewers can learn the details of some of these unexplored issues, and get behind-the-scenes information and curriculum materials from consultants and the production team.

Despite the limitations, I remain convinced that “reality history” is a potentially powerful way to introduce the past to a wide audience comprised largely of people who have no desire to read lengthy academic books on early America. I would like to think that Colonial House at least gave us a different view of the remote past than the stereotypical textbook treatment we remember from high school. Some K-12 teachers and college professors have already told me they plan to use the show in the classroom. With any luck, it may also stimulate people to go to Plimoth and other living-history museums, where they can get a more detailed and nuanced view of early American life. I also hope Colonial House showed how important and relevant our past can be when we try to sort out complex modern-day issues like race, gender, and religion.

So would I do it again? Absolutely. I have spent my career as a historian and archaeologist trying to understand what life was like for the inhabitants of early New England. Last fall I had the opportunity to walk into a version of that past, and to share that experience with a few million students of history. Flaws and all, it was the opportunity of a lifetime.

This article originally appeared in issue 4.4 (July, 2004).

Emerson “Tad” Baker is chair of the history department at Salem State College. His current book project is Lithobolia, or the Stone-Throwing Devil of New England. Details on his archaeological excavations on early Maine sites can be found here.