Looking South: The Mexican Isthmus Through Gringo Glasses

On April Fools Day in 1857, an article just two sentences long appeared on the front page of The New York Times, announcing the U.S. government’s plan to purchase Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec for $15 million. It was no joke, but why did the U.S. government want to buy (at a bargain-basement price) the Mexican isthmus? The word “Tehuantepec” hasn’t appeared on the front page of the New York Times since 1938. These days, most people in the United States have never heard of the region. But in the 1850s, it was as familiar as Puerto Rico is today.

The New York Times began publication in 1851, less than three years after the U.S. annexation of northern Mexico—what would become California, Oregon, Washington, and several other U.S. states—after the U.S.-Mexico War. During its first two years in publication, the Times ran hundreds of articles about the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. A news column titled “Isthmus of Tehuantepec” appeared regularly in the newspaper’s front section.

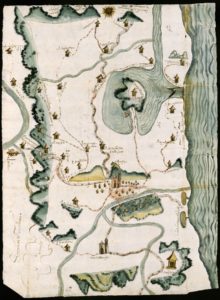

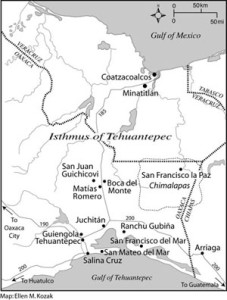

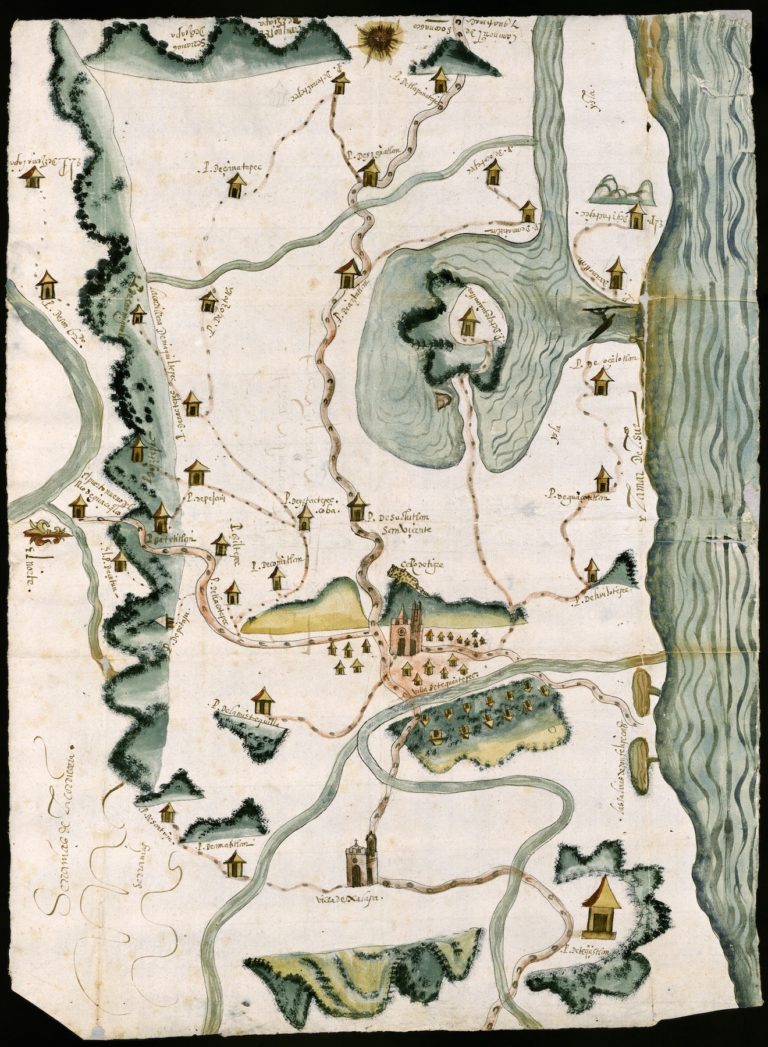

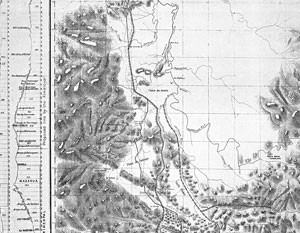

Mexico’s Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a 120-mile-wide slice of land that stretches east-west, connecting the Yucatan Peninsula to the rest of Mexico. An 1865 U.S. atlas shows the isthmus as a separate state, not part of the states of Veracruz and Oaxaca, as it is today. In the left corner of that map, there is also a detailed map of the isthmus—the only part of the country the cartographers chose to show in detail for a U.S. audience. Why so much attention from U.S. cartographers, politicians, and journalists devoted to a tiny sliver of Mexican land?

To understand that flurry of nineteenth-century interest in a region now little known to us, we must to turn our attention to the narrow dirt road that cut across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec a century and a half ago. In 1853, four years before that two-sentence New York Times cover article announced U.S. government designs on the isthmus, local residents there seceded from the states of Oaxaca and Veracruz, announcing a new Mexican state, with its capital in the city of Tehuantepec. In 1855, a group of New York investors completed a railroad across the Panamanian isthmus, at that time still part of Colombia. And finally, just four months before the April Fools Day story, a U.S. company completed the “Tehuantepec Turnpike”—an earthen path wide enough for a stagecoach—running from the Coatzacoalcos River that drained into the Gulf of Mexico and La Ventosa Bay, on the southern, Pacific coast of the isthmus.

The Tehuantepec Turnpike opened a decade after the U.S. annexation of northern Mexico. Even more important, it came a decade before the completion of the first U.S. transcontinental railroad. The U.S. government, and its corporations, urgently needed a faster route between the country’s east and west coasts. In an era when transport was primarily via water, U.S. leaders looked south. In the years that followed the annexation, plans for the next North American grab (or purchase) of Mexican lands became a regular topic of debate on the pages of U.S. newspapers. Should the United States annex Baja California? The states of Sinaloa and Sonora along the Sea of Cortez? Or Tehuantepec? The Mexican isthmus offered the United States a link between the east and west coasts of our suddenly vast country.

At that time, there were only two routes for mail and news between New York and San Francisco. One was the Pony Express, a network of riders who made the dangerous two-week trip across snowy mountain passes and dry plains. The other route took nearly as long, via ship from the East Coast, then railroad across the Panamanian isthmus, then another ship to the West Coast. Tehuantepec offered the third option. In November 1858 the first bundles of “California mails” arrived in the Gulf port of New Orleans, having traveled from San Francisco via the Tehuantepec isthmus. The packages arrived in New York a full week earlier than those shipped via Panama. New York Times articles about the new western territories began by noting, “The mails have arrived from Tehuantepec.”

A Times article published in February 1858 declared, “[L]et a stable government be established and the tide of American progress will set resistlessly toward the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.” There was regular steamer service between the U.S. Gulf coast and the Mexican port city Coatzacoalcos. The next logical step was to transform the dirt-road turnpike into a state-of-the-art planked roadway. Huge crates of wood for building frame houses arrived from Florida and construction workers arrived from New York with four months’ provisions.

Those U.S. workers showing up to transform the built environment of the Mexican isthmus continued a trend started by those who had built the Tehuantepec Turnpike. The word turnpike, meaning toll road, comes from the Middle English words turne pike meaning “spiked barrier.” The name probably seemed particularly appropriate to the istmeños—the local residents—when gringos showed up with steamer boats, scythes, and rifles to cut a stagecoach road through field and forest.

The hundreds of Times articles published about the Mexican isthmus between 1851 and 1858 focused on its role in U.S. hemispheric interests, and on the natural resources available there for exploitation. In the late 1850s, with a small but significant number of North Americans living in the region, daily events on the isthmus became worthy of detailed description. Here is one example from the northern isthmus city of Minatitlán, in 1858:

The river at this time is quite high, though as yet we have had no flood. Should we not have one, many of those engaged in the mahogany cutting will be unable to get out their year’s work, and will thus be greatly injured pecuniarily….

The town is improving. Carpenters command good wages; that is, from $2.50 to $3.50 per day. We have but very few here sick, and it may be said that the health of the town is very good. Most people upon their arrival have a slight attack of the calentura, but with care, and a low diet, it soon passes off. It is generally brought on by mixing fruit and liquor, and strangers can rarely be induced to believe the mixture injurious until they have felt the effects of indulgence.

The opening of the Tehuantepec Turnpike made both mahogany-cutting and colonization possible. A few years after the turnpike was completed, a French visitor to the isthmus noted that the region’s forest was “overly frequented by the North Americans, and had already lost a large part of its virgin beauty.”

Upbeat reports of the expanding U.S. presence in isthmus towns were one of three types of articles that appeared in the Times during this period. The other two often contradicted each other. Opinion leaders in Washington, D.C., and New York promoted the region’s positive attributes, including vast natural resources and purportedly good weather. An 1858 New York Times editorial noted: “The route passes through a healthy and delightful region, and when opened will be a favorite with the traveling and trading public.” On-the-ground reports from North American travelers rendered a more complicated reality. Just two months before that editorial appeared, a traveler from San Francisco, John Hackett, complained in a long letter to the editor about “the rays of burning sun.” Anyone who has traveled at midday on horseback in the isthmus region—as nineteenth-century travelers did—knows that Hackett came closer to the truth.

On February 19, 1858, John Hackett boarded a southbound ship called Golden Age in San Francisco. Six days later, in Mexico’s Pacific port of Acapulco, he and fifteen others disembarked, then boarded the steamer Oregon, bound for the Mexican isthmus, which lay further south. There should have been sixteen traveling with him, Hackett reported, but one of the passengers, “while under mental aberration, superinduced by whiskey,” had climbed off the Golden Age and drowned.

Oregon reached La Ventosa Bay, at night. Around daybreak the following morning, March 1, two metal boats arrived shipside to take both travelers and baggage to shore. Huge waves pummeled the Oregon, threatening to smash the small boats against its hull. After the passengers flung their trunks and themselves from ship to boat, seven istmeños rowed them to shore. Both the harshness of the local environment and the skill of the local boatmen in overcoming it impressed Hackett. Twenty yards from shore, the boats bottomed out. The indigenous longshoremen jumped into the water, hauled the boats onto their shoulders, and carried the travelers to dry sand.

The travelers then entered the customs office, a thatched-roof hut, before slogging three-quarters of a mile through the sand to board a stagecoach for the city of Tehuantepec. Three hours later they had traversed the fifteen miles “of tolerably smooth road” to arrive in the city of Tehuantepec. The easy ride ended there. After that, Hackett reported, the ride on the Tehuantepec Turnpike was “jolting to such an extent as to pound one almost to the consistency of a jelly.” When the path was too rough for the stagecoach, the passengers rode horseback.

About the time they passed what is now Matías Romero, one man “got off his animal, staggered and fell.” They managed to carry him to a nearby camp, but there was no one to offer medical help. He died about fifteen minutes later. He carried $1,300 worth of gold—a goldrusher returning from the West Coast with the loot he panned from California’s rivers. The gold that was once Mexican returned to Mexican soil.

The travelers finally reached the end of the stagecoach line, at the town of Suchil—the dateline for many New York Times articles about the isthmus. Hackett noted dryly that the long-anticipated Suchil was “an imposing city of three staked wig-wams and one wooden house.” The steamer to New Orleans was supposed to meet them there, but since it was the dry season, the Coatzacoalcos River ran too low to be navigable. Hackett bragged that he and his traveling partners rowed themselves down the river in a dugout mahogany canoe for a day and a half, with nothing but river water to sustain them.

When he finally reached New Orleans on March 9, Hackett wrote to the editors of The New York Times immediately. His long account ended, “I have detailed without the slightest exaggeration my actual experience across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and regret that these embarrassments to the perfect success of the route exist.” He concluded that the geography of the region “must ever be a stumbling block in the way to the perfect success of the [trans-isthmus] route.”

In spite of Hackett’s pessimistic testimonial, news articles datelined Minatitlán or Coatzacoalcos reflected a bustling Isthmus of Tehuantepec that resembled any North American Wild West outpost. September 1858: “We stand in need here of a newspaper, and a cabinet-makers’ shop.” August 1859: “Quite a number of wealthy Mexicans from the City of Mexico are now on the isthmus locating lands and taking up territory, which they feel satisfied must soon come under the United States.”

In early New York Times articles about North American expansion on the isthmus, local residents were rarely mentioned. But as the carpetbaggers began to face hard times in the late 1850s, news articles focusing on native istmeños began to appear for the first time. The Times correspondent in Minatitlán noted in 1859:

The new church is to be dedicated to-morrow, and I have never heard so much noise, and of such variety, on any similar occasion. First, there is the constant firing of an old gun near the church, then the ringing of a half-dozen bells which have been gathered from wrecked vessels…The natives, large and small, male and female—but particularly the latter, who are the most pious—have been busy for several days in toiling earth from a neighboring hillside, in aprons, bags, and turtle shells, and depositing it near the church. The people here are very cleanly in their habit, and are perfectly honest. Mechanics drop their tools on the spot where they work, and nothing is ever taken. No one thinks of locking his doors here as a security against thieves.

Even as New York Times writers and editors seemed to perceive the isthmus in the most utilitarian terms—a short path between the oceans—the place still held mystery. Their reports exoticized it, suffused it with an other-worldly quality. As one article put it, the place had a “lifeless and dreamy appearance.” The journalist continued, “The rainy season has commenced, and the few showers we have already had have covered the surrounding mountains with verdure. I returned from Ventosa this morning and was delighted with the variety and fragrance of the flowers which literally perfumed the lonely forest-road…” (The writer conveniently leaves out the mosquitoes, also brought by the rains, which in turn brought yellow fever.)

The optimism about the region’s potential for the U.S. government, then focused on the realization of Manifest Destiny, was short-lived. In September 1859, newspaper headlines hinted at boom towns busting: “Isthmus of Tehuantepec: Rainy and Sickly Season—Desperation and Hard Swearing Among The Employees—Robbery of the California Mail—New Rumors, &c” With temperatures topping 120 degrees and foreigners sweating out severe fevers, looters attacked the incoming ships from the United States, robbing passengers and pilfering the mail. The Tehuantepec Turnpike collapsed into economic ruin. Gringos who had traveled to the isthmus looking for jobs and opportunity languished, unable to afford return passage home.

Tensions rose between the istmeños and gringos. By February 1860, U.S. Marines were stationed at the isthmus city of Minatitlán, supposedly to protect North Americans living there from Mexican soldiers. Istmeños became outraged at the presence of U.S. troops in their towns. Mexican government officials demanded an explanation from the U.S. consul in Minatitlán: what was the U.S. military doing on the isthmus? According to a New Orleans journalist living in Minatitlán, the consul insisted, “[T]he United States of America had the right to send their men-of-war to any part of the globe where they had fellow countrymen to protect.” Minatitlán’s North American enclave began to fear “the seizure of all American property and the assassination of American citizens.” The tension led to a Mexican-only meeting, at which “the discussion was long, heated and acrimonious. Finally, after four hours’ deliberation, it was decided that the Americans, in the port of Minatitlán, be treated coldly but politely, until sufficient force be obtained to drive them out.” Even the New Orleans journalist acknowledged, if indirectly, that the North Americans lived on isthmus land without the blessing of the istmeños.

As the situation became more difficult for North Americans on the isthmus, the political situation shifted back in the United States. The conflict between the U.S. North and South grew, exploding into the Civil War in 1861. The Union government feared the growing economic power of the Confederate South. Suddenly, cargo ships moving busily between Coatzacoalcos on the isthmus and the Southern ports of Mobile and New Orleans were seen as a threat bolstering the Confederacy’s economy.

From those southern ports, the Gulf port of Coatzacoalcos is less than half as far as the Panamanian isthmus. However, Panama lies so far east that it’s slightly closer to New York than Coatzacoalcos is. As far as northerners were concerned, the Tehuantepec isthmus offered no geographic advantage over the Panamanian isthmus. With the U.S. South economically and politically weakened by the Civil War, U.S. government and corporate interest in Tehuantepec faded.

However, once the Civil War ended, the political winds shifted back; interest in the Mexican isthmus rose again. An economically prosperous U.S. South was no longer perceived as dangerous, but necessary. In 1867, just two years after the war’s end, a U.S. company based in New Orleans signed an agreement with the Mexican government to build a railroad across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. A U.S. Navy expedition, led by Robert Wilson Shufeldt, was sent to survey the region for a new transcontinental transit corridor. The group, which included hydrologists, astronomers, engineers, naturalists, photographers, and meteorologists, arrived in Minatitlán on November 11, 1870. The expedition’s long report to the U.S. government included everything from the region’s hydrology, to lists of native plants, to a short glossary from the local languages of Zapotec and Zoque. The report was enormously detailed, cataloguing the type of soil under every isthmus village they visited, the type of rock on every hill they climbed, the location and appearance of each tree species that gave them shade.

The report is remarkable in both its precision and its single-mindedness. The lists of animals, minerals, soils, plant species, and local vocabularies have a relentless focus: assessing the usefulness of the natural resources for commercial exploitation. Shufeldt’s findings were encouraging, from the perspective of North American industrialists. Nonetheless, they received scant mention in The New York Times. A single sentence appeared on the newspaper’s front page in April 1871, datelined Mexico City, announcing “the discovery of a practicable route” across the isthmus.

The dream of a U.S.-controlled transit corridor was foiled again in 1871, this time by events in Mexico. Political unrest exploded following the close presidential race between Benito Juárez and Porfirio Díaz. The North Americans still living in the isthmus region were caught up in the violence. When posters appeared on their front doors threatening their lives, they abandoned their cotton plantations and mahogany sawmills. Their letters tell of their panicked departure: “We must abandon the Isthmus to God and the Mexicans.” “The foreigners are flying for their lives.”

English capitalists saw opportunity in the North Americans’ flight. With Canada’s growing autonomy, England sought another path across the Americas to India. The U.S. looked on grudgingly, considering it “England in our waters.” The U.S. government worried about the threat to North American supremacy in the region, whining that Mexico was only doing twice as much trade with the United States as it was with England. An 1885 article, reprinted from The Mexican Financier, ascribed ulterior motives to England’s interest in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec: “It may be that English diplomacy would like to build up on the southern border of the United States a strong nation, not openly hostile to American influence on this continent, but yet quietly exerting a counteracting force to American supremacy.”

In spite of gringo fears, a joint British-North American company finally completed construction of the first Mexican trans-isthmus railroad in 1894. On September 11 of that year, the inaugural train made the trip from the Gulf port of Coatzacoalcos to the Pacific port of Salina Cruz in ten hours and twenty minutes. TheTimes reported, “The Mexican Government is determined to make the National Tehuantepec Railroad a great international traffic route. In order to bring about the desired result extensive improvements will be made to the harbors of Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz …” Still, after investing somewhere between $25 million and $50 million, the isthmus had only, as the Times put it, “utterly worthless track.” By the turn of the twentieth century, the railroad offered nothing to international commerce. Though still viable for local transit, its tracks were unable to support the weight of loaded boxcars, while the ports at either end were far too small for seagoing ships.

Meanwhile, U.S. government attention had shifted south, to digging a canal across newly independent Panama, where both land and government seemed more compliant.

Further Reading

An earlier version of this essay appears (in Spanish) in the book Región del Istmo de Tehuantepec: Interacciones sociales y flujos comercios, published in 2011 by the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (Center for Advanced Studies and Research in Social Anthropology) in Oaxaca, Mexico. Portions of it also appear in Wendy Call’s new book No Word for Welcome: The Mexican Village Faces the Global Economy (Lincoln, Neb., 2011).

In addition to the digital archive of The New York Times, available at many libraries, two articles provide key historical detail about Mexico’s trans-isthmus railroad: Paul Garner’s “The Politics of National Development in Late Porfirian Mexico: The Reconstruction of the Tehuantepec National Railway 1896-1907,” from the Bulletin of Latin American Research 14:3 (1995) and Francie Chassen-López‘s “El Ferrocarril Nacional de Tehuantepec,” from Acervos 10 (Oct.-Dec. 1998). Dr. Chassen-López’s book, From Liberal to Revolutionary Oaxaca: The View from the South, Mexico 1867-1911 (University Park, Penn., 2004), offers a deeper sense of the economy and society of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the late nineteenth century.

This article originally appeared in issue 11.4 (July, 2011).