Money Talks

Listening to the history of value

In 1601, strapped for funds and pressed for time, Elizabeth I ordered her mints to create new Irish coins that were short on silver. She used the base money, adorned with the same harp that the Tudors had traditionally chosen for their Irish coinage, to pay her royal army to put down the Ulster confederacy. Her strategy captured as profit the difference between the face value of the new money and its lower metallic value. At the same time, Elizabeth outlawed use of the old coins with higher silver content; these became bullion, available to be minted into the new currency. In a stroke, Elizabeth had raised a revenue without recourse to Parliament, its delays, and its demands. A few years later, a common law court confirmed the Queen’s sovereign authority to declare the denomination, weight, and worth of money. The new coins circulated, silver “harps” of a literally lighter note.

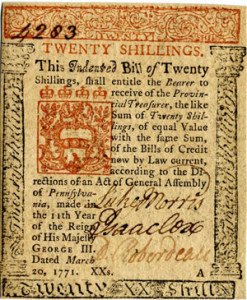

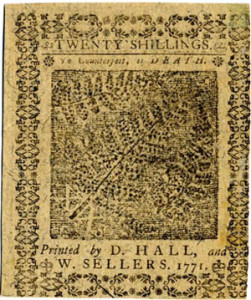

In 1768, a group of countrymen from Chester County, Pennsylvania, suggested a radically different way of making money. Four years before, Parliament had prohibited American legislatures from issuing colonial paper notes for legal tender, triggering a currency scarcity that bore down on the small rural producers and consumers of the state. Their solution was as bold as Elizabeth’s: let the general assembly issue paper without any official status; the people of Pennsylvania by mutual pledge would “receive the bills . . . in discharge of all debts and contracts, and in the business of trade and commerce to all intents and purposes as if they were made and declared by law to be legal tender in all cases whatever.” In other words, the people would cooperate in treating a homemade money with no legal backing as if it were the officially sanctioned medium. If they had been able to pull it off—had they convinced the legislature and maintained their pledge—the money would have succeeded, its value founded on their collective commitment rather than the sovereign’s authority. The money, we might imagine, would have looked much like the bills of credit produced during the period before the Act of 1764: rough prints of surprising beauty, often bearing a provincial symbol—the pine tree or the fox, a snake, sailing ship, or colony seal, edged with garlands or a scrolled pattern.

A revolution later, Robert Morris argued that the emerging states required a very new sort of money. According to his Report on the Public Credit, sent to Congress on July 29, 1782, the war had demonstrated that Americans must anchor their system on silver and gold specie with a value set by international exchange. Specie would be multiplied by credit—notes borrowed by governments or private individuals—that would lubricate the productive activities of enterprising men. The public role here was neither to decree value nor to coordinate its creation. Rather, Congress would set up a structure within which individuals would act according to their own ends, unlocking the “secret hoards” of precious metal they had long since hidden, lending, borrowing, investing in an economic whirl that would energize the new nation. Morris proposed a new unit for the federal coinage: the “mill,” which would be defined according to a standard metallic content of one quarter grain of silver and would, by factoring easily into the heterogeneous state and foreign currencies then circulating, ease conversion to the new national money. Morris even had prototypes of his proposed money minted: the legend Nova Constellatio encircled a sunburst of rays that emanated from an Eye of Providence; thirteen stars surrounded the sunburst and the back of the coin bore the words Libertas-Justitia. At the same time, Morris worked to convert the Continental dollars owed American troops into interest-bearing IOUs.

The harps of Elizabeth, the paper money imagined by the people of Chester, and the specie-and-debt combination proposed by Morris are more than historical tokens, intriguing material artifacts of their times. They are also more than ornaments on the political dramas that produced them: the tragic policy of Elizabeth towards the Irish, the ineptitude of Parliament confronting a rising American population, or the early nationalist impulses of American economic elites. Rather, currencies are the language of value, and like other languages, they convey a history, if we can hear it. Embedded in the currencies of Elizabeth, Chester, and Morris are three distinct theories of value—or, more precisely, three constitutions or regimes of practice that produced value. These distinct approaches to the creation of value illuminate the political economies of their times. In so doing, they allow us to reconsider mercantilism, to define capitalism in new ways, and to recognize alternative forms of value creation that we’ve previously neglected. More generally, they suggest the need for a history of the way we produce value, as well as meaning, and the way we distribute value, as well as meaning, in selective ways.

The Queen and the Irish Harp

When Elizabeth debased the Irish harp, she acted against a well-recognized baseline. Value, at the turn of the sixteenth century, was widely understood in a particular way: it was a real or tangible resource to be collected, controlled, and distributed by a sovereign. The character of money lay at the heart of that practice, with all its political and legal complexity, its material impact, and the conceptual categories that attended those dimensions. Through its medium, a particular approach to value penetrated the constitutional relations of mercantilism, the precapitalist belief that value was acquired not made.

Listen to the reasoning of the court that legitimated Elizabeth’s act. The political message is perhaps the most conspicuous. According to the judges, the King’s power to make money was enormous; he alone could make money “of what matter and form he pleaseth,” determining its weight, denomination, fineness, and stature as legal tender. Generally, monarchs used metallic tokens, convinced that value depended on the amount of precious metal captured in the coin. Likewise, the more gold or silver a country monopolized, the wealthier would be that polity. Sovereign power and control over value were joined at the root.

Even more striking, the King alone could “by his prerogative . . . put a price of valuation on all coins”—and he could change that valuation at will. The King could, in other words, drastically affect the fortunes of men: “so may he change his money in substance and impression, and enhance or debase the value of it, or entirely decry and annul it, so that it shall be but bullion at his pleasure.” Moreover, the monarch acted without recourse to Parliament; in such a regime, the King could raise revenue and save a kingdom, all without asking Parliament to levy a tax.

But an approach to value that placed it largely in the hands of a sovereign was not a regime without law. To the contrary, the judges located the rationale for “a standard of money” in a notable place: the need for individuals to contract with each other. “For no Commonwealth can subsist without contracts,” they observed, “and no contracts without equality [of terms], and no equality in contracts without money.” The need for a token that held a value constant between holders, if not a value consistent over time (given debasements), in turn supported the monarch’s prerogative to determine value. And if debasement for good cause was legal—and the judges clearly determined it to be within the common law—then the redistribution of property that it entailed was legal as well. This regime thus embedded in legal relations an order that expressly encompassed sovereignty over private resources, with organizing effects on the social, political, and material hierarchies that resulted.

The dynamics of the system stretched from exceptional cases like the Irish harp to everyday practice. Economists have argued that regimes relying on coins supposed to be worth the intrinsic value of their metallic content could not regulate amounts of small change in circulation; early modern rulers regularly debased currency in order to cure shortages of coin—not always because of their designs on revenue. That is, an approach to value that identified it as inhering in real resources brought with it the practical consequence of devaluation, a dynamic that then had to be managed, politically and legally. That project would affect basic categories like rights and property as participants rationalized the political economy they created. For example, early English judges created mechanisms, like the petition of right, that bound the Crown to repay public creditors while preserving its ultimate discretion over the value of that payment. The courts granted no such latitude to participants in private contracts. The division distinguished the standards that bound public and private entities, an orientation that affected how rights against the state were defined, where “rights” themselves were located (in the community or the individual), and when individual interests should give way to the claims of the public.

In the end, the Elizabethan categories used to understand governance, the definitions given property and rights, and the power granted the sovereign all related intimately to an approach to value that treated it as a tangible resource to be garnered and dispensed across a kingdom coordinated at the center.

Paper Models of Value

Acting out of a world still organized around the tenets of mercantilism, colonial Americans invented another approach to value. The paper money proposed in Chester followed seventy years of experimentation and turned on the insight it had produced: value was a functional concept that could be created by collective action. Since the early eighteenth century, Americans had circulated public “bills of credit” (essentially IOUs) as money when, like the inhabitants of Chester, they lacked silver and gold. Local communities issued non-interest-bearing notes (notes stating a government obligation) to pay their creditors. Those IOUs could be submitted or “retired” to pay for tax obligations; in the interim, they functioned as silver or gold currency because they would be as good as silver or gold for future public payments. As modern macroeconomists have shown, the notes carried real value because the collective practice of issue and retirement created a value-bearing asset out of them, at least as long as people could predict that they would be taxed.

The new approach to value radically redistributed political authority. Provincial assemblies, formally prohibited from controlling expenditures, took charge of public spending when they invented a money under their own auspices. They now paid public creditors, directed appropriations, and made land-based loans. The issue of paper money thus fueled the famed “rise” of the American assembly in each colony: legislators exercised increasing authority in practice and began to assert rights against the imperial order more aggressively.

Even more startling was the power now claimed by taxpayers: monetary policy depended on their votes, and the stability of economic value depended on their compliance with levies. When they cooperated, taxpayers financed the expenses of the public by meeting those obligations. But when inhabitants were strapped by war or economic distress, tax defaults rose and money depreciated. In those circumstances, taxpayers forced a new mode of finance into effect: the public debt was paid off as the money used for common expenses lost value in the hands of those holding it; those holders absorbed the loss if and when the drop in value became permanent. Participants understood the dynamic; Franklin called depreciation “a tax on money, a kind of property very difficult to be taxed in any other mode.” Communities in turn debated its consequences, often taking political measures to reallocate the losses that followed devaluation. The high profile of each monetary experiment—pamphleteers advertised how bills of credit operated in order to establish their legitimacy and secure their acceptance—emphasized the role of participants. The small size of each colony made the system even more transparent.

Those circumstances changed the consciousness of participants. They became, first, increasingly aware of their provincial integrity. The effort to maintain a local money trained attention on the boundaries of the community: the system depended on the actions of residents, used provincial obligations as its linchpin, and created value only within domestic borders. The Chester petitioners thus identified the virtue of earlier paper money exactly in its quality as “a medium of commerce issued to the people, which from its nature was not subject to be transmitted to the mother country.” Provincial boundaries in turn underscored the politics within each community. Legislators became increasingly sensitive to the electoral debate over money. Populist rhetoric rose, heightening popular expectations of involvement. The Chester experience again provides an example: someone printed the petition to the general assembly as a broadside—and inspired colonials from Philadelphia to the frontiers of the province to submit similar pleas, close to sixty petitions in all. Finally, pointing to the local boundaries and effects of monetary decisions, participants began to identify as a priority the economic development of themselves and their communities. The pro-paper propagandists that dominated in most of the colonies developed arguments for opening up markets to the middling men of their provinces. As the Chester petitioners summed up the operation of local paper, “from its permanency among us, the merchant, farmer and mechanic were always able to obtain a proper currency, by which they could conveniently fulfil their engagements.” These were not, however, proto-capitalists—their arguments stressed access to the market for newcomers over security within it for those with material investments, unlike the arguments several decades later.

Again, the practice of value affected the very categories used to constitute the community. “Politics” ranged American actors against imperial ones on a new issue, value, which had been a central attribute of English sovereignty. More subtly, within the colonies themselves, monetary policy and market access became core matters of popular and legislative debate. That debate in turn implicated and was itself influenced by basic legal categories: bills of credit were “contracts” that linked the public to those holding its bills. As political decisions and economic circumstances changed the value of money, participants molded the jurisprudence of contract to explain, justify, or challenge those events and the claims of participants. As John Adams said, defending an episode of devaluation in 1780, “[t]he public has its rights as well as individuals, and every individual has a share in the rights of the public. Justice is due to the body politic as well as to the possessor of the bills; and to have paid off the bills at their nominal value would have wronged the body politic.”

In the paper approach to value, then, the community organized its roles and defined basic notions like “rights” by reference to a value they expressly produced out of the collective contribution—only some called it confiscation—of all members. The approach reconstituted the imperial design for the colonies into a new corporal order.

Capitalism and a New Coin

Robert Morris wrote his Report on the Public Credit near the end of a war won largely, if painfully, on the power of paper money. His report was organized around that history; it articulated the old system and argued for a new one. Here for the first time, politics was moved to the periphery—Morris put it there with a flourish, all to emphasize the space made for the productivity of private men. In the new approach, the state would be understood as a frame for the creation of value by individuals.

The money at the center would again be metal, but Morris assumed a kind of currency far removed from the Irish harp. Apparently projecting a specie supply with a price set stably by international exchange, he happily excluded politicians from controlling quantities of money in circulation. He then advocated adding a rather new device: instruments of public debt. Unlike taxes, which quickly became burdensome to taxpayers (and, because their weight was “more sensible,” invited protest too easily), government borrowing could raise revenue without any discernable impact on the citizenry. In the meantime, participants multiplied their money with the interest-bearing notes that public borrowing produced—they added to the currency, in other words, again apparently without the intervention of politicians. Indeed, state legislatures at the end of the decade would struggle to defend the very institution—control over money—that had earlier won them so much power.

As for the problems associated with debt, Morris dismissed them with the fuel that powered the whole system—individual productivity. Borrowing paired with that tonic drive had, in his view, only one result—economic growth. Farmer after farmer who borrowed to improve his land earned more than enough to pay back his loans—Morris chose his hypothetical deliberately and, he may have felt, quite diplomatically. The same logic would work in the aggregate: government would borrow and use the money to good effect. The economic growth that followed would make paying off the principal easy and make the country wealthy. In the meantime, the system would tie public creditors, those most able and entrepreneurial in Morris’s view, to the new nation.

The political economy that Morris anticipated would be as publicly structured as the regimes improvised by Elizabeth or the American provincials. When the Federalists accepted many of the tenets proposed by Morris, they had also to construct the collective conditions that would make it operate. Politics, that is, did not so much recede as change its shape. A freely floating metallic money did not, as it happened, produce sufficiently stable prices without complex interventions: the negotiations necessary to run a bimetallic system or maintain the gold standard consumed seemingly limitless political energy in the nineteenth century. Legislatures at the same time lost their power to add to the money supply if specie was scarce and prices fell—but until foreign money arrived seeking bargains, representatives could borrow instead. Public debt provided the new means of public finance, and private credit, generated by the new national bank and its state counterparts, further multiplied available gold and silver. The debate over economic policy continued with new contours.

Likewise, the law developed for an earlier approach to value was revised for the new order; Americans did not suddenly discover “rights” that would make the new system work—they redefined them that way. Courts and legislatures developed doctrines of negotiability and dismantled other safeguards, like requirements restricting transferability, which had traditionally been attached to legal contracts. As for the government’s obligations under public instruments—bonds now rather than money—arguments drawn from private law furnished new models that disallowed devaluations like those that had occurred in the colonial world. The courts, with their orientation towards individuated disputes, became the oracles of “contract,” and legislatures, formerly the brokers of complex revaluations that balanced individual and group claims, retreated from the responsibilities to recalibrate value they had claimed in the earlier system. The “public,” once conceived as a distinctive entity with organic significance became an aggregate of individuals, a transformation that boosted the leveling rhetoric of individualism, even as it ceded populist claims based on shared economic circumstances.

If Morris’s system was as publicly structured—indeed, as controversially constructed—as previous orders, what was new was its approach to value. Recognizably capitalist, that approach defined politics as a framework for value produced by private activity and investment. Citizenship itself reflected the revision: investing in the government for profit became a public service, lauded and promoted. The boundaries that defined politics as a setting for individual entrepreneurial action depended on the courts; their developing doctrines drew new lines that marked financial gains largely as private. Increasingly, the market appeared independent of the very materials that had created it, reinforcing a gathering assumption of its autonomy. The capitalist approach to value, in other words, itself conditioned the world in ways that located the political as legitimate insofar as it supported liberal individual agency.

A History of Value

The transformations told by money matter enormously. The Irish harp, the paper proposed by the Chester petitioners, and Morris’s specie-and-debt system were very different media, designed to produce value in very different ways. Those approaches to value organized the constitutional systems in which they occurred. They changed divisions of authority, including those between law and politics and between public and private. They redistributed material power, variously allowing monarchs, taxpayers, and public creditors to claim the resources of others. They forced their creators to invent concepts as distinct as a “public contract” and the “autonomous market.” Those concepts, claims, and divisions of authority mark our world as surely as money. They are, in fact, carried into practice with every exchange of that medium, as the stories above reveal. Value, as much as meaning, has a history.

Further Reading:

For an account of Elizabeth’s debasement, see Edward Colgan, For Want of Good Money: The Story of Ireland’s Coinage (Wicklow, Ire., 2003). Her strategy was validated in “The Case of the Mixt Money, 2 James I” (1605), in Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials (London, 1809): 114-130. Economists Thomas Sargent and Francois Velde model the difficulties of supplying early modern communities with small change in The Big Problem of Small Change (Princeton, 2002).

The petition submitted by the inhabitants of Chester is “To the Honorable the Representatives of the Freemen of the Province of Pennsylvania . . . The Petition of the Inhabitants of the County of Chester,” AAS Broadside 41096 (1764) [sic]. (The correct date appears to be 1768 or 1769, according to Terry Bouton’s history). Terry Bouton writes about the petitioning efforts of Pennsylvanians and the conditions that catalyzed it in his dissertation, “Tying Up the Revolution: Money, Power, and the Regulation in Pennsylvania, 1765-1800.” Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 1996: 49-80. Christine Desan reviews the macroeconomic models that explain how American paper money held value and considers that money as a form of governance in “The Market as a Matter of Money: Denaturalizing Economic Currency in American Constitutional History,” Law and Social Inquiry 30 (Winter, 2005). The quote from Benjamin Franklin comparing depreciation to a tax on money appears in “Of the Paper Money of the United States of America,” Albert Henry Smyth, ed., Writings of Benjamin Franklin IX (New York, 1907): 231, 234. John Adams’s language appears in his letter to the Comte de Vergennes, June 22, 1780, in Francis Wharton, ed., The Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States (Washington, D.C., 1889): 810-812.

Robert Morris submitted his Report on the Public Credit, July 29, 1782,to Congress on August 5, 1782; it is reprinted in Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789,vol. 22 (Washington, D.C., 1914): 429-446. A short history of his attempt to establish a mint is available at the Website of the beautiful Coin and Currency Collections of the University of Notre Dame. For the authoritative account of the financing of the American Revolution, see E. James Ferguson, The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance, 1776-1790 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1961). The complexities of establishing and maintaining the gold standard are accessibly suggested by Barry Eichengreen, in Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (Princeton, 1996).

This article originally appeared in issue 6.3 (April, 2006).

Christine Desan teaches law and legal history at Harvard Law School. She is at work on a history of the political economic world of colonial Americans called The Practice of Value before the Coming of Capitalism: Money as Governance in Early America.