Pilgrims in Print: Indigenous Readers Encounter John Bunyan

While fleeing Boston to evade his indenture, Benjamin Franklin saved a man from drowning. Crossing Hudson Bay in 1732, Franklin’s boat was driven onto the shore of Long Island. In the confusion, one passenger—“a drunk Dutchman”—fell overboard, and Franklin pulled him back on board by his hair. As a reward, the rescued man presented Franklin with his “old favorite author Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in Dutch, finely printed on good paper with copper cuts.” Franklin then paused to meditate on Bunyan’s importance to the English book trade and English literature: “ . . . it has been translated into most of the languages of Europe, and suppose it has been more generally read than any other book except, perhaps, the Bible. Honest John was the first that I know of who mixes narration and dialogue, a method of writing very engaging to the reader.”

Franklin was right on both counts. Pilgrim’s Progress (1684) was ubiquitous across the British Empire. In the first eighty years of American imprints, only John Bunyan and Isaac Watts issued from American presses at least once each decade. Pilgrim’s Progress appeared both in fancy dress, trimmed in fine copper engravings like those of Franklin’s gift, and humble fustian—Isaiah Thomas’s American edition sports only rude woodcuts and a duodecimo format suggesting a humble clientele. Bunyan’s masterpiece adorned the stalls of bookshops in Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. Yet it also turned up in the North Carolina backcountry, at one William Johnston’s general store. The pervasiveness of these colonial editions was mirrored across the English book trade as a whole. As in America, the non-conformist allegory met with brisk sales in the English countryside and in remote foreign missions. Sometimes it was even translated into the local idiom. Before he arrived from Shropshire to become a printer of government documents in Annapolis and Williamsburg, for example, William Parks published a Welsh-language edition of Pilgrim’s Progress.

The one thing Franklin did not foresee, however, was the critical role Bunyan’s book would play in European colonization, especially among the Protestant missionaries who fanned out across the globe in the nineteenth century. By the 1840s, missionary publishing houses like the American Tract Society were extolling the cross-cultural potential of Pilgrim’s Progress. In its 1848 guidebook for colporteurs, the society argued that Bunyan’s book “suits all the various descriptions of persons who profess godliness . . . The child may read it for intense interest for the story . . . and as he advances in the Christian course he will read it again to learn the Christian warfare.” Though these comments were primarily directed at the book’s reach across Anglo-American social strata, coded within terms like “heedless youth” and “Christian warfare” are implicit references to indigenous peoples and imperial rule. Throughout the nineteenth century, natural historians and theologians alike characterized the Native peoples of Africa, Australia, and the Americas (as does Favell Mortimer’s 1844 Ojibwa language tract) as “but children in understanding; and the more simple the form of thought and language in which instruction is conveyed to their minds, the more perfectly do they comprehend it.” The remarks about Christian warfare similarly speak to what literary theorists describe as the “linguistic colonialism” practiced by missionaries, whose activities included the burning of Mexican codices, forced European literacy education, and the outlawing of rival vernacular cultural linguistic and ritual practices.

A religious steady-seller that outlived its non-conformist cultural roots, Pilgrim’s Progress had joined a growing list of titles generated by an emerging circum-Atlantic missionary print network. A subset of the larger English book trade, this system vigorously promoted works like Bunyan’s allegory as “plain” texts whose piety was intimately linked to their cheapness and ease of reading. Because such works were “short, and . . . plain,” one proponent of this system explained, everyday readers “cannot fail of understanding.” Their cheapness and availability assured that they would be “always at hand, and read over often.”

Such books grew even more popular as English missionaries shrewdly exploited the business side of the trade to entice wider circulation. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), for example, solicited contributions from “Corresponding Members” giving them bound tracts at cost, so that they could easily dispense them to rural and distant clergy and laity alike. What began as a marketing ploy rapidly took the form of an ad hoc print network that stretched across the Atlantic.

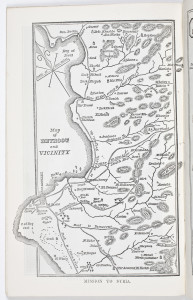

By the nineteenth century, this evangelical print consortium had matured into a full-fledged national distribution network, as missionary printing concerns like the American Bible Society and the American Tract Society were founded in major eastern seaboard cities, with satellite publishing hubs in Lexington, Kentucky, and Cincinnati, Ohio, that facilitated expansion into the American West. The missionary print system embraced cutting-edge technologies like stereotype printing, steam presses, and paper making, thereby keeping down costs to realize the SPG’s vision of Christian books “always at hand.” In 1810 the American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was formed to extend these networks worldwide, their yearly fund-raising publications featuring maps that located their missions in a world system of Christian education. Pilgrim’s Progress was ideally suited for this market.

As Isabel Hofmeyr has observed of the eighty translations of Bunyan that circulated in colonial Africa, the book was a quintessential “translingual mass text.” Its production and circulation within indigenous societies forged a hybrid sort of discourse, pitting the missionaries’ “relentless imperialism” and faith in the universal translatability of Christian doctrine against local understandings of storytelling and representation, and alternative views of the role alphabetic literacy might play in colonized communities. Unlike editions of Bunyan that were produced for the Anglo-American colonial public (or the rural poor of Wales), indigenous language editions of Bunyan’s masterpiece expose print’s potential to generate unforeseen material practices on the periphery of the British book trade. Vernacular language translations of Bunyan’s work also yield surprising insights into their production and consumption, revealing multi-cultural (multi-ethnic?) social networks that challenge hegemonic models of the relationship between colonialism and print culture.

Missionaries and their indigenous parishioners in Canada and the United States were in the vanguard of this movement. In 1842, Pilgrim’s Progress was printed in Native Hawaiian under the title Ka Hele Malihini Ana. Bunyan’s book was again published in an indigenous language in 1858, when the American Tract Society printed a Dakota version, Mahpiya ekta oicimani ya; John Bunyan oyaka. In 1886, the London-based Religious Tract Society released The Pilgrim’s Progress . . . translated into the language of the Cree Indians. At the turn of the twentieth century, two more North American vernacular editions were created. Takkorngartaub Avertarninga (1901), also printed by the Religious Tract Society, was sent to a Moravian Inuit mission in Labrador. In 1904, Mennonite missionaries released a Cheyenne-language edition of Bunyan, Assetosemeheo heamoxovistavátoz na: (1904) for use in present-day Oklahoma.

Ka Hele Malihini Ana was translated by the Rev. Artemas Bishop, a New Yorker who had sailed to Hawaii with the second wave of ABCFM missionaries in 1823. Well regarded for his translation abilities, Bishop had been in Hawaii for nearly 20 years before he attempted to make Bunyan available in the islanders’ language. It is likely he took that time to absorb traditional Hawaiian storytelling practices, for he—like many ABCFM missionaries—had been instructed to evangelize the local population with some eye toward indigenous cultural preferences.

The title page of his edition bears this out, offering linguistic evidence that the Native idiom helped him shape the book’s presentation in ways to make it more accessible to the locals. The full title of the Hawaiian translation in modern orthography is Ka Hele Malihini ‘ana mai kēia Ao aku a hiki i kēlā Ao; He ‘Ōlelo Nane i Ho‘ohālike ‘ia me he Moe ‘Uhane lā, which roughly translates into The First/Foreign/Stranger’s/Visitor’s Travel from this World to that World; A Riddle/Puzzle/Allegory Similar/Compared to a Dream.

Malihini, here acting adverbially in describing the verb hele (to go), is the word Bishop used for the English word “pilgrim.” Malihini can suggest a range of concepts that connect to being new or unfamiliar to a place, person, thing, or practice—or simply being inexperienced or ignorant. Malihini is often paired or contrasted with the word “kama‘āina,” which refers to being well-acquainted with a place, person, thing, or practice, or to be from a particular area. Malihini are guests, while kama‘āina are often their hosts, and each status comes with a particular set of responsibilities.

These responsibilities are made legible in the proverb “ho‘okahi lā o ka malihini,” or “one day as a visitor.” It means that malihini are always welcomed, given food, and shelter on the first day of their arrival, but after that, they are expected to pitch in and start helping the kama‘āina, their hosts, with whatever needs to be done. Once the relationship between the malihini and the particular place, person, etc. grows, the malihini actually can, after a great deal of time and effort, become a kama‘āina, which generally has a more positive connotation.

Thus, this section of title implies (for Hawaiian readers) a journey being undertaken by a stranger or someone unfamiliar with the area and its culture. It hews closely to an English-speaker’s understanding of pilgrim, but also carries with it the trace connotation that such pilgrims are a bit foolish and ignorant. The general expectation of a malihini is also that she will try to become more kama‘āina, so it is likely that Hawaiian readers of Ka Hele Malihini Ana would understand that the journeys Bunyan describes are similar to those that the pilgrims/malihini take when seeking knowledge to become kama‘āina. Kama‘āina is a compound of kama [child] and ‘āina [land], and the sense of familiarity denoted by kama‘āina comes from the idea that someone is a child of the land, or a long-time resident. Thus, the knowledge needed to become kama‘āina in the Hawaiian sense does not come through heavenly salvation from God, but from the very earthbound and worldly knowledge of the land, through the actual traversing of the land and speaking with the people.

Finally, Bishop’s translation of “dream” as “moe‘uhane” further extends these allusions to local cultural practices. This Hawaiian word translates into something like “spirit sleep,” a concept drawn from Hawaiian belief that dreaming is the journey that your spirit takes while you sleep. It implies a certain kind of travel that “dream” does not, and refers to pre-Christian Hawaiian belief, further undermining the Christian message intended by the translation.

Despite the potential for cultural dissonance raised by certain elements of the translation, the mission had high hopes for its edition of Bunyan. In 1841, Artemas Bishop confidently wrote to the mission board: “If I do not much miscalculate on probabilities it will prove one of the most popular works in the Hawaiian Language.” Yet by all accounts, it was a bomb. The Hawaiian-language Bible had just been published in its entirety three years prior, and it was still enjoying massive popularity. Ka Hele Malihini Ana had an initial print run of 10,000 copies, but in two years, only 3,600 copies were distributed among the missions and schools. For the next nine years, the bindery reported no movement of the remaining 6,000 copies, the bulk of which were given away at the turn of the century to Chinese merchants to wrap their vegetables.

Some have attributed its failure to the fact that Hawaiians found the book incomprehensible because of the allegorical personal and place names—Evangelist, Mrs. Filth, Giant Despair, Lucre Hill. Yet, the fact of the matter is that the meanings of Hawaiian personal names and place names often played a large role in traditional Hawaiian mo‘olelo (story/account/history/legend) and that Hawaiians were already very familiar with this sort of allegorical story. The Hawaiian appreciation for kaona—essentially a sort of directed meaning through metaphor, allusion, and implication in which different messages were encoded for different audiences in the same sign—meant that most stories would automatically be read for allegorical intent. The problem, then, was that while Ka Hele Malihini Ana fit very easily into the genre of a kaona-laden mo‘olelo, but turned out not to be a very good example of that genre. While examples of kaona in Hawaiian poetry and mo‘olelo were often quite ribald, the artistry and subtlety of the way someone employed kaona was what was actually valued, and Ka Hele Malihini Ana, with characters named things like Christian, Mr. Worldly Wisdom, Hopeful, and Great-Heart, would probably have been seen as just too obvious.

Although many contemporaries hailed Bishop as a very good translator, as he had worked on several sections of the Bible and other books that were more successful than Ka Hele Malihini Ana, one crucial change in his translation strategy proved to be debilitating. Bishop was so confident in his own abilities that he

Dispense[d] with constant native aid, . . . merely . . . read[ing] over with care the manuscript copy to a few judicious natives, and to adopt such of their corrections as appeared proper.

This strategy may have worked for his later translations of primers and the like, but Ka Hele Malihini Ana was meant for popular use. Bishop would have done well to consult with those Hawaiians such as Kuakini, John Papa ‘Ī‘ī, Kamakau, Hoapili, and David Malo, who had previously assisted him on the form and approach of the translation, as many were themselves keepers of traditional moʻolelo and could have guided him in shaping the translation to fit Hawaiian tastes, rather than relying on “a few judicious natives” merely to check grammar and offer “corrections.”

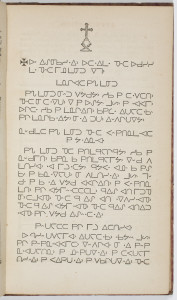

Thomas Vincent’s 1886 translation of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress into Cree syllabics has much in common with Bishop’s Hawaiian version, except for the fact that Vincent was of Cree ancestry. A native speaker of the language, Vincent was thus able to avoid the errors that befell Bishop’s Hawaiian edition. Just one in a long line of English-language religious texts translated into Cree syllabics—the Holy Bible, the Common Book of Prayer, and numerous collections of hymns preceded it—Vincent’s work exemplifies how evangelization and vernacular literacy were entwined in the Canadian north from the seventeenth century forward, as they were elsewhere across the globe.

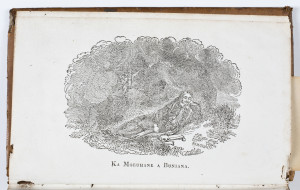

From its title page on, the physical properties of Vincent’s text suggest that it was a production of much more limited resources that Bishop’s version of Pilgrim’s Progress. The cover is plain, the typeset quality poor, the illustrations are randomly placed with no relationship to the text, and are likely drawn from different European editions. Unlike other nineteenth-century Cree syllabic translations, Vincent follows the convention of word separation with limited punctuation. While he does employ commas, even an exclamation point here and there, he generally reserves periods for scripture quotations.

For a modern Cree reader, reading Vincent’s syllabic text is time-consuming and difficult. At the time of its publication in 1886, there existed only one system of syllabics for the Cree language. Today there are two, Western Cree syllabics and Eastern Cree syllabics, each with its dialectical variances, in addition to a standardized Roman orthography (SRO). Vincent’s syllabic translation contains what might be considered archaic glyph forms that are no longer used and a number of differently or misspelled words when translated into SRO. For example, the title in Cree syllabics translates into SRO as two words: opapâmohtêw (one who walks) and either ê-pimipicim (a misspelling of either opimipiciw [the traveler]) or ê-pimimipicit (as s/he travels about). It is likely that the Cree title for The Pilgrim’s Progress is “One Who Walks as S/he Travels About.” Bunyan’s subtitle, In the Similitude of a Dream, is not translated or otherwise included in the Cree syllabic edition. As there are no gender pronouns in Cree, the gender of the “walker” would be determined by the translation, illustrations, and the individual reader. If Vincent’s translation were read aloud to an audience, as was also likely, the composition of the audience and the context of the performance would also be factors in the determination of gender. What is most interesting about this translation is the omission of Christian’s name. Vincent refers to Christian through non-gendered Cree verbs. Similarly, there is no direct translation for “pilgrim” in Cree; the concept did not exist at the time of the original translation. Even today, it is not listed in either the Alberta Elders’ Cree Dictionary or The Student’s Dictionary of Literary Plains Cree, the two most utilized print dictionaries for the language.

Vincent’s method of translation is what today would be called free translation—a direct, literal translation into Cree would have been for the most part impossible. Beyond the difference in cultural concepts such as “pilgrim” and “celestial,” there are differences in language structure. There are no adjectives in the Cree language; rather, they are expressed through the use of verbs. Time is also figured differently in a Cree context, and is expressed as such within Vincent’s translation. For example, when the giant Despair threatens to rip the pilgrims to pieces in ten days, Vincent translates this as “I will do this to you before it will be the tenth day.”

Cree narrative practices are also embedded in the translation. Many sentences begin with phrases such as “So this way, s/he tells about …” and “So far, again …” or “Happening, right now …” These initial phrases are a way of structuring the narrative to indicate continuous action in a communal storytelling setting. Although the translation was intended to increase individual literacy and encourage solitary reading practices of suitable material, Vincent’s translation was undertaken in such a way as to make Bunyan’s seventeenth century, very English religious allegory congruent with Cree narrative practices.

Vincent’s translation also provides valuable information about language shift, changes in word usage, and indigenous narrative structure in this Cree community. More significantly, however, it shows how important the context of production (or translation) is when indigenous translators have performed the work. One of the most important contexts for understanding the Cree edition of Bunyan is Vincent’s biography. The grandson of a Scottish Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader and his Cree wife, Vincent found little opportunity for advancement in the economic structure of his time due to his mixed race status. He turned instead to the Church of England, working as a laborer, teacher, translator, catechist, and clergyman. Throughout his time in the church, he worked in remote northern missions established to evangelize the Cree and Ojibwa in what was then called Rupertsland. He is said to have been against the use of the drum and other traditional spiritual practices. Vincent was eventually given the honorific of Archdeacon, but never achieved the title of Bishop. He took on the translation project of his own accord, and although approved by his superior, John Horden, bishop of Moosonee, Vincent traveled to London at his own expense to oversee the printing process, an expense that was routinely covered for non-Native clergy.

It is against this backdrop of social, economic, and political marginality that the Cree edition of Pilgrim’s Progress achieves a very different form of “engagement” from that Benjamin Franklin spoke of in his autobiography. As Arlette Zinck and Sylvia Brown observe in their comparative study of Canadian First Nations editions of Bunyan (“The Pilgrim’s Progress Among Aboriginal Canadians”), Vincent’s translation and publication of the text served as a “passport into a world into which he didn’t quite belong: the educated, Christian, and British missionary culture.” Through the Cree syllabary Bunyan, Vincent hoped to engage simultaneously with Britain’s global missionary and imperial enterprise as well as the oral, narrative traditions of his homeland.

In this way, Vincent’s adaptation of Pilgrim’s Progress shares with its many indigenous language contemporaries interesting social contexts for the hit-or-miss effectiveness of such books in Native communities, their manner of composition, and their divergent afterlives in the communities they were produced to serve.

In the case of Stephen Riggs’s Mahpiya, there was little initial interest in the book among the Dakota until the mass imprisonment of more than 200 men, women, and children in 1862 in the aftermath of what the whites called the Dakota Uprising led to an urgent need for written communication between separated family members and with legal representatives.

Once in prison, Dakota who before ridiculed English-language literacy now begged for lessons in vernacular reading and writing. In true evangelical fashion, Stephen Riggs attributed the uptick in requests for literacy education among the Dakota imprisoned at Mankato as evidence that Native prisoners had realized that “The power of the white man had prevailed; and the religion of the Great Spirit, or the white man’s God, was to be supreme.” Riggs called it “a revolution in letters,” and stood amazed at how reading becomes “a perfect mania” among the prisoners; men and women of 60 years were trying to read. After quickly exhausting 400 copies of the little spelling book he had “improvised and printed at St. Paul,” he turned to his edition of Bunyan and distributed at least 100 copies to the prisoners. The apparent success of Pilgrim’s Progress among the imprisoned Dakota later inspired the ABCFM to stereotype Riggs’s translation in 1892, but these later editions exhibit little use, and it appears that Dakota language speakers much preferred the vernacular Bible and hymnals in their own language to the Christian conversion story as sources for learning to write the vernacular for use in legal and political battles.

In Hawaii, Artemas Bishop’s edition of Bunyan served green grocers better than parishioners for similar reasons. Not only did the story not match up well with Kanaka Maoli cultural practices, but also its deployment of the vernacular proved much less useful than the collaboratively produced primers and tracts that served as a critical foundation for the Native Hawaiians’ growing and substantial vernacular language print culture of newspaper articles, essays, and broadsides.

Reading from just a few of the hundreds of indigenous language editions of Pilgrim’s Progress that flowed from English presses in the nineteenth century, we experience print cultures whose conceptions of both “print” and “culture” were as divergent as the languages and peoples they engaged. At the same time, the diversity of uses to which different communities applied these versions of Bunyan suggests the fluidity of the book trade as a medium in forging new kinds of social connections both within and without indigenous societies. Men like Artemas Bishop and Kuakini, Stephen Riggs and Joseph Renville, and Thomas Vincent and John Horden worked together to make Bunyan “engaging” to generations and communities for distinctly local purposes, and in the process helped produce reading and writing publics whose engagement reached beyond mimicry to promote the radical restructuring of societies under siege by European imperialism.

Further Reading

Clifford Canku and Michael Simon, ed. and trans., The Dakota Prisoner of War Letters (Minneapolis, 2013).

Patricia Demers, Naomi McIlwraith and Dorothy Thunder, eds. and trans., The Beginning of Print Culture in Athabasca Country (Edmonton, 2010).

Puakea Nogelemeier, Mai Paʻa i ka Leo: Historical Voices in Hawaiian Primary Materials, Looking Forward and Listening Back (Honolulu, 2010).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.4 (Summer, 2015).

Stephanie J. Fitzgerald (Cree) is associate professor of English at the University of Kansas. She is the author of Native Women and Land: Narratives of Dispossession and Resurgence (University of New Mexico Press, 2015).

Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada believes in the power and potential of ea, of life, of breath, rising, of sovereignty, because he sees it all around him, embodied in the ʻāina, the kai, his family, his friends, and his beautiful community. He is a PhD candidate in English at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, focusing on translation theory. He is editor of the journal Hūlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being, and works as a Hawaiian-language editor and translator.

Phillip Round is professor of English and American Indian and Native Studies at the University of Iowa. His most recent book, Removable Type (2010), was awarded the Modern Language Association’s James Russell Lowell Prize. His current research has been supported by a John Simon Guggenheim Fellowship.