Publick Occurrences 2.0 February 2008

February 29, 2008

Seems Like Old Times, I: Nationalizing the state militias

One of the features I have planned for this blog is a series of items highlighting issues from the Early Republic that have come back or never gone away.

One of those issues is the drive to concentrate as much control as possible over the nation’s armed forces in the federal government and its military leadership. A perennial sticking point in this drive has been what used to be called the state militias, known in modern times (speaking broadly) as the Reserves and the National Guard. As both military officers and civilian officials, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton were famously dissatisfied with their dependence on poorly trained and equipped militia troops, questioning the citizen-soldiers’ ability to stand and fight against regular troops, and, just as importantly, doubting their reliability when called upon to apply force to their fellow citizens in times of domestic unrest.

During the French war scare of the late 1790s, the Federalist Congress authorized President John Adams to call out 80,000 militiamen and create a 10,000-man Provisional Army in case of a declaration of war or foreign invasion. Nothing was ever done with this authority except the appointment of a few officers. Instead, Adams, Hamilton, and other Federalists struggled to create (with different agendas) a sizable Additional Army that, along with volunteer units who paid for themselves, would be usable “at the President’s discretion” whether there was a war or invasion or not. [The clearest explanation I have ever found of these matters is: William J. Murphy Jr., “John Adams: The Politics of the Additional Army, 1798-1800,” New England Quarterly 52 (1979): 234-249.]

Admittedly I found the story several weeks ago, but I find it interesting, more than two centuries later, when Reserve and National Guard units have been deployed overseas for years at a time, and on regular basis, that the Pentagon feels that it still does not have enough control of state troops and also wants a greater role in policing what I guess we now have to call the “homeland.”

Pentagon control over Reserves, Guard proposed

By Philip Dine

POST-DISPATCH WASHINGTON BUREAU

Friday, Feb. 01 2008

WASHINGTON — More than six years after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the nation’s plans for meeting the threats to the homeland are so thin they could be written “on the back of an envelope,” the chairman of a national military commission said Thursday.While the country has detailed contingency options for military action overseas, the capacity for responding to a terrorist attack or natural disaster within the United States is dangerously low, retired Maj. Gen. Arnold Punaro, chairman of the Commission on the National Guard and Reserves, said Thursday.

“You couldn’t move a Girl Scout unit” with the amount of planning federal officials are doing for domestic contingencies, he said, likening it to a disorganized “sandlot game.”

“You cannot do that in dealing with weapons of mass destruction,” Punaro said.

Among the shortfalls are a lack of equipment for the National Guard, with Missouri and Illinois particularly hard hit in some categories, according to the commission’s report released Thursday.

The panel called for a drastic overhaul of the military structure that would put the National Guard and Reserves under the direct control of the Army and Air Force and essentially integrate the nation’s “citizen-soldiers” into the military structure. The plan would include integrated training, pay, promotions, medical care and retirement — and improved resources and equipment.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon would be put in charge of homeland security, which would be carried out by the Guard and Reserves.

Those changes are necessary both to meet homeland security shortfalls and to allow the over-extended military to focus on overseas missions, commissioners said. Many can be implemented by the Pentagon while some require legislation by Congress.

The Guard’s current status made sense during the Cold War when it was “designed as a reserve force to be dusted off once in a lifetime,” but no longer when reservists are being used as a wing of the military, Punaro said. The current problems are heightened by the personnel limitations of an all-volunteer military, he said.

The commission, which was authorized by Congress, found that the only other alternative for dealing with a stretched-thin military — increasing the size of the active-duty component — is prohibitively expensive.

Adding the 600,000 active-duty soldiers that would be required for current needs would cost more than a trillion dollars, Punaro said. Beyond that, the military couldn’t recruit enough people to meet that target, he said.

Not only are there enough reserve forces to take over homeland security, they are highly skilled and are already in the states and cities, he said.

February 28, 2008

Barack Hussein Obama: Inheritor of an All-American Semitic Naming Tradition

Juan Cole had great post yesterday, in part explaining the Semitic origins of the names of a long list of presidents and other American heroes. Here is one of the key passages:

Let us take Benjamin Franklin. His first name is from the Hebrew Bin Yamin, the son of the Right (hand), or son of strength, or the son of the South (yamin or right has lots of connotations). The “Bin” means “son of,” just as in modern colloquial Arabic. Bin Yamin Franklin is not a dishonorable name because of its Semitic root. By the way, there are lots of Muslims named Bin Yamin.

As for an American president bearing a name derived from a Semitic language, that is hardly unprecedented.

John Adams really only had Semitic names. His first name is from the Hebrew Yochanan, or gift of God, which became Johan and then John. (In German and in medieval English, “y” is represented by “j” but was originally pronounced “y”.) Adams is from the biblical Adam, which also just means “human being.” In Arabic, one way of saying “human being” is “Bani Adam,” the children of men.

Thomas Jefferson’s first name is from the Aramaic Tuma, meaning “twin.” Aramaic is a Semitic language spoken by Jesus, which is related to Hebrew and Arabic. In Arabic twin is tau’am, so you can see the similarity.

James Madison, James Monroe and James Polk all had a Semitic first name, derived from the Hebrew Ya’aqov or Jacob, which is Ya`qub in Arabic. It became Iacobus in Latin, then was corrupted to Iacomus, and from there became James in English.

Zachary Taylor’s first name is from the Hebrew Zachariah, which means “the Lord has remembered.”

Abraham Lincoln, of course is, named for the patriarch Abraham, from the Semitic word for father, Ab, and the word for “multitude,” raham,. Abu, “father of,” is a common element in Arab names today.

So, Mr. Cunningham, Barack Hussein Obama fits right in this list of presidents with Semitic names. In fact, we haven’t had one for a while. We are due for another one.

February 27, 2008

Scary Pictures

An outbreak of anti-Obama Muslim-baiting flared up recently after a controversy over Clinton campaign’s alleged “circulation” of an old photo of Barack trying on traditional Somali garb on a congressional garb, in the dress-up routine innumerable politicians have been subjected to over the years. That controversy, and some likely Clintonian pressure, led even respectable mainstream media sources Tim Russert and CNN to make a number of crude, witless efforts to link Obama with hated Muslim or Muslim-ish figures like Louis Farrakhan and the dictator of Libya, the latter of whom is actually chummier with the Bush administration than Obama. In what I expect to be be a campaign comedy cliché by week’s end, Hillary Clinton and America’s Toughest Dumb Journalist made a big stink at the last Democratic debate about trying to pin down on the literally meaningless question of whether Obama would merely “denounce” Farrakhan (the weaker option, apparently) or “reject” his support, whatever that means. I am picturing Obama campaign operatives waiting in ambush at Farrakhan’s Chicago polling place to make sure their candidate doesn’t receive his support.

Of course, as an early political historian, the use of an image to “other” an opposition political figure in the eyes of religious and patriotic voters, reminded me of the famous Jefferson cartoon from the election of 1800, one of the very few cartoons from that era. Jefferson’s only suspect article of dress is a cloak — to hide his shame, no doubt — but the effect is pretty similar, the candidate’s true, anti-American self revealed. There was also quite a lot of Federalist verbiage along the lines of calling on Jefferson to denounce and reject the French Revolution, Thomas Paine, the Enlightenment, the opposition press, and many of his own writings. I can picture Tim Russert reading Jefferson’s infamous letter to Philip Mazzei aloud during an Adams-Jefferson debate and truculently demanding what Jefferson could do to reassure English-Americans that he did not consider their mothers harlots.

February 21, 2008

The Evitability of the Inevitablity Strategy

The primary campaign is by no means over, but the media and the blogosphere have now realized that the unstoppable Hillary Clinton juggernaut they have been building, image-wise, for these past 3 years is, in fact, eminently stoppable. The inevitable Democratic nominee is now one more big loss away from having to get the nomination Corrupt Bargain-style, and/or risk digging herself an even deeper hole by breaking out the racial codewords again. That seemed to work short-term in New Hampshire but also galvanized black primary voters down south behind Barack Obama and turned the race around. Ezra Klein of the The American Prospect has one of the better recent commentaries on Hillary’s troubles, “The Underperformer.”

We historians know that Olympian historical contextualization of everyone else’s opinions is a sure way to alienate friends and family, so I say, keep it on the blog. To wit:

As historians could have told Hillary, and the media, “inevitability” is about the most evitable thing in politics. Has the “inevitability strategy” ever worked? Let’s ask the long line of prohibitive front-runners whose proud ships ran immediately aground as soon as actual voters were sighted: Ed Muskie, Nelson Rockefeller, Mitt Romney’s dad, the list could go on and on. I remember when John Connally and Howard Baker were big presidential names. Incumbent presidents have gotten the nomination through inevitability, only to have it flop in the general election. Remember Carter and Bush I’s Rose Garden strategies?

Inevitability may have worked occasionally in the Early Republic, for John Adams in 1796 and James Madison in 1808, but that was before such a thing as a nomination process was even invented. Alexander Hamilton’s plan of swapping Adams for a Pinckney might have done the job if there had been a Federalist Super Tuesday in 1796 or 1800. De Witt Clinton might have given Madison quite a shock if could have taken him on in a Pennsylvania or Massachusetts primary. Congressional caucus nominations meant never having to burst the Beltway bubble, if I may be permitted one final anachronism, er, counterfactual.

Back here in the modern world, when will the media learn that those early poll numbers measure nothing but name recognition? For the vast majority of citizens who do not follow politics closely, telling a pollster that they supported Hillary Clinton for president 1 or 2 years before the election was more akin to saying yes, they had heard that the most famous woman in America (non pop-star category) was running for president against that Jock Edwardson — the haircut guy — and noted Irish revolutionary or Muslim poet Brock O’Bama.

Once the identities of everyone else in the race came into focus, Hillary Clinton’s weaknesses as a candidate did likewise: she was a deeply polarizing figure who brought along most of her husband’s baggage — especially his penchant for calculating triangulation — and little of his charisma; she was on the wrong side of the issue that Democratic primary voters cared most about, the war; and her track record of “proven leadership” began with mismanaging the only real chance at national health care the U.S. has had in my adult life. In addition, she just has not run a very effective campaign. How could Clinton possibly have been such a towering figure in the Democratic party for as long she has and still not have state organizations strong enough to do well in caucuses and navigate the delegate selection rules? Like most inevitable front-runners, she took the DC-centric view that fundraising and press coverage was more important, and waited for the electoral tides to come in. Oops.

February 20, 2008

Another dog in the hunt

Turns out there is yet another Lewis, Clark & Dog monument in the St. Louis area, this one down on the waterfront by the Arch (see below). It appears not to be as big, or as accessible, but just as canine-centered as the one in suburban St. Charles. The earlier post’s comments included some worthwhile links for those who want to explore the history of pets. One of the commenters also pointed out that Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dog Fala appears in one of the scenes at the FDR monument in Washington. Unfortunately, unless the D.C. representation of Fala is approximately the size of a bear, which I do not remember, it is no match for the Seaman of St. Charles.

February 19, 2008

Wisconsin Primary Cheesehead Special: Andrew Jackson’s even more mammoth cheese

In honor of the primary election being held today in America’s Dairyland, I offer a fromage-related item that recently came to my attention. (Sadly this post does not actually mention Wisconsin.) As many readers of the blog will know, I wrote an article a few years back on the Mammoth Cheese presented to Thomas Jefferson by the dairy farming Baptists of Cheshire, Massachusetts, in 1802. (It was published as a chapter in the Beyond the Founders collection I co-edited with David Waldstreicher and Andrew W. Robertson, but seemingly read by far more people in the earlier version posted on my web site.) One of those readers, Loyola College student Erin Bacon, wrote last week with news that I had missed the biggest cheese of all, a 1400-pound specimen that is apparently common knowledge among residents of Oswego County, New York. I had mentioned a 100-pound cheese sent to Andrew Jackson by a Cheshire couple, but Ms. Bacon’s “local pride” impelled her to inform me of her hometown’s far more imposing tribute, a dairy product that was indeed as giant as Old Hickory’s self-regard. She sent a link to an old Oswego County history available online. Here is the account from 1895 Landmarks of Oswego County:

Dairying, and especially cheese-making, had become an important industry, particularly in the south part of the town [Sandy Creek, NY] in the Meacham neighborhood. In 1835 it made the locality famous. Col. Thomas S. Meacham was a man of enthusiastic temperament and fond of remarkable things, and in that year he conceived the idea of making a mammoth cheese as a gift for President Jackson. He had 150 cows, and for five days their milk was turned into curd and piled into an immense cheese-hoop and press constructed for the purpose. The cheese weighed half a ton, but was not large enough, so the colonel enlarged his hoop and correspondingly enlarged the cheese until it tipped the scales at 1,400 pounds. It was then started on its journey to Washington. Forty-eight gray horses drew the wagon on which it rested to Port Ontario, whence it was shipped November 15, 1835, the boat moving away amid the firing of cannon and the cheering of the people. Colonel Meacham accompanied it. It was conveyed by water by way of Oswego, Syracuse, Albany, and New York, and along the entire route its projector was given a series of ovations. Reaching Washington the huge cheese was formally presented to the President of the United States in the name of the “governor and people of the State of New York.” In return General Jackson presented Colonel Meacham with a dozen bottles of wine. The mammoth production was kept until February 22, 1836, when the President invited all the people in the capital to eat cheese. The scene is thus described by an eye-witness:

This is Washington’s birthday. The President, the departments, the Senate, and we, the people, have celebrated it by eating a big cheese! The President’s house was thrown open. The multitude swarmed in. The Senate of the United States adjourned. The representatives of the various departments turned out. Representatives in squadrons left the capitol – and all for the purpose of eating cheese! Mr. Van Buren was there to eat cheese. Mr. Webster was there to eat cheese. Mr. Woodbury, Colonel Benton, Mr. Dickerson, and the gallant Colonel Trowbridge were eating cheese. The court, the fashion, the beauty of Washington, were all eating cheese. Officers in Washington, foreign representatives in stars and garters, gay, joyous, dashing, and gorgeous women, in all the pride and panoply and pomp of wealth, were there eating cheese. It was cheese, cheese, cheese. Streams of cheese were going up in the avenue in everybody’s fists. Balls of cheese were in a hundred pockets. Every handkerchief smelt of cheese. The whole atmosphere for half a mile around was infected with cheese.

Colonel Meacham also sent a cheese to Vice President Van Buren, another to Gov. William L. Marcy of Albany, a third to the mayor of New York, and a fourth to the mayor of Rochester, each weighing 700 pounds. In return he received from the latter a huge barrel of flour containing ten ordinary barrels.

My Mammoth Cheese article made no pretensions to cataloging every single instance of presidential food tributes, but I will say that this Super-Mammoth Jacksonian Cheese makes one of my points fairly well. Thomas Jefferson’s cheese was a homely salute from a whole community, and it had a political message — New England Baptists’ support for Jefferson’s free-thinking, tolerant approach to religious freedom and many common Americans’ excitement at what promised to be a more democratic era. Jefferson’s Federalist opponents, still clinging to power in many places, sneered at the gesture and turned up their noses at the cheese. (It did smell.)

On the other hand, at least from the account above, Jackson’s cheese was something of an advertising stunt*, and only political in the sense of being the then-existing political establishment’s tribute to itself. A hard-charging local entrepreneur conceived the idea, and Whigs and Democrats and all of Washington society embraced it. Like most of the political festivities of the mid-19th century (as opposed to the earlier period), the Jacksonian Mammoth Cheese was bigger chiefly in the amount of money and ballyhoo that went into it.

*I wonder if the writer of the children’s book I complained about in the article, A Big Cheese for the White House, conflated the two cheeses. In that story, it was the original Mammoth Cheese that was an advertising stunt.

Superdelegates team up against the Spectre (of a brokered convention)

Following up on the earlier “brokered convention” post, I noticed that at least some of the key “superdelegates” (Democratic officeholders who can vote for any candidate they please) seem to share Ed Kilgore’s fears of a convention fight. Rep. Charles Rangel and Sen. Charles Schumer were both quoted warning the Hillary Clinton forces against relying on superdelegates or parliamentary maneuvers (like the seating of delegates selected in the non-sanctioned Michigan and Florida primaries) to take the nomination away from Barack Obama at the convention:

“It’s the people (who are) going to govern who selects our next candidate and not super delegates,” Rangel said Sunday night at a dinner for the New York State Association of Black and Puerto Rican Legislators conference in Albany, N.Y.

“The people’s will is what’s going to prevail at the convention and not people who decide what the people’s will is,” he added.

This a better argument than the fear of a chaotic convention projecting a bad image for the party.

The idea that the party’s decision should reflect “the people’s will” can be traced back to Jacksonian and “Old School” complaints about the use of congressional and legislative caucus nominations back in the 1810s and 1820s. The Democrats adopted the delegate convention system partly in response to the past outrage over the denial of the nomination and the presidency in 1824 to alleged popular favorite Andrew Jackson. 1824 front-runner William Crawford was nominated by the Democratic-Republican congressional caucus despite the fact the candidate was medically incapacitated and the competing candidates’ supporters boycotted the caucus. Party mastermind Martin Van Buren and other Crawford supporters then discovered first hand how perilous and self-defeating it was to seize the nomination for their favorite when the perception existed that a majority of the party did not support him.

You have to admit that it would be fun if the first black presidential nominee ends up owing his nomination partly to Jacksonian arguments.

February 15, 2008

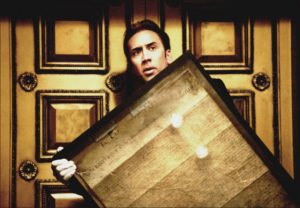

Nicolas Cage, National Menace

Most people, even most historians, do not seem to share my degree of detestation for the National Treasure movies starring the once-noted thespian Nicolas Cage. The first one finally caught up with me on a trans-Atlantic flight a couple of years ago. Now, as readers of this blog will discover to their peril, I am not remotely averse to popular culture, even when it takes some liberties with early American history. Cotton Mather as a super-villain? No problem! Who doesn’t love a mind-controlling Puritan with a fire-shooting cross? I can tell you from personal experience that reading those comics as a kid only made it more interesting to learn who Mather really was when I got older.

But National Treasure? Holy hand grenades, Batman, that thing combines the egregious dumbness of most pop-culture historical window dressing with an earnest “love” of history as treasure hunt and Chamber of Cool Secrets that resonates unfortunately well with the version of actual history sold on basic cable and the sale table books at Barnes & Noble. It also feeds into the public tendency to treat great historical documents like holy relics with special powers rather than texts with content and context. The real Declaration of Independence, with its complicated backstory and sometimes paradoxical legacy, can’t compete with the one that has a treasure map on the back or might be worth somethin’ if you find a copy in Granddad’s old truck. Actual anecdote there.

I understand that even most average moviegoers do not consciously take a dopey thriller like National Treasure seriously, but I also know that people do pick up information from sources like that, especially if they know little or nothing else about the subject. Hollywood should consider how wide an array of topics that statement covers. In National Treasure (and The Da Vinci Code), a wide international audience was exposed to the basics of a number of legends and conspiracy theories that had previously been limited to devotees of paranoid pseudo-knowledge, and the scholars who follow them. Now I see that the federal government has actually found it necessary to put on an exhibit correcting the misinformation on the Great Seal of the United States, a.k.a. the brand of masonic slavery, that the Cage vehicles have spread.

Were the brain cells Nic destroyed with Con Air and Ghost Rider not enough? Did he have to go after our history as well?

UPDATE: No sooner did I finish writing the post above last Friday, did I get in a car and hear a cutesy NPR piece on the same exhibit. While the reporter took one of those audibly, breathily grinning tones that drive me nuts, and while she let the curator cover the Great Seal myths debunked, the story begins with the voice of Christopher Plummer (from the movie) reciting the myths in much more dramatic and convincing form.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.3 (April, 2008).

Jeffrey L. Pasley is associate professor of history at the University of Missouri and the author of “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (2001), along with numerous articles and book chapters, most recently the entry on Philip Freneau in Greil Marcus’s forthcoming New Literary History of America. He is currently completing a book on the presidential election of 1796 for the University Press of Kansas and also writes the blog Publick Occurrences 2.0 for some Website called Common-place.