March 31, 2008

Barack Obama, Glenn Loury, and the American Historical Narrative

Over at TPM Cafe, former black conservative Glenn Loury of Brown University has an interesting if rather slippery essay on Barack Obama’s race speech. Loury was once groomed by Marty Peretz and The New Republic as a black writer who would say negative things about the black community (a prized commodity in those emerging neocon circles) and picked by the Reagan administration for a high position the Education Department. Loury has moved left since the 1980s, and in his TPM piece seems to find in Obama a threat to black radicalism as represented by what I guess we would have to now call traditional black political spokesmen like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton.

Bizarrely, in course of making a none-too-original inauthenticity argument, Loury charges Obama with doing almost the opposite of what he actually did in The Speech. To me, Obama’s great accomplishment was demurring from Jeremiah Wright’s views while acknowledging and accepting that those views stemmed organically from the real feelings and experiences of Wright’s generation. That was the aspect of the speech that had conservative racialists like Pat Buchanan howling that the speech was “the same old con, the same old shakedown that black hustlers have been running since the Kerner Commission.” Yet here’s Loury attacking Obama from the opposite direction, or almost both at once:

I can’t get past the fact that Obama was negotiating with the American public on behalf of MY people in Philadelphia last week. In the process, he presumed to instruct a generation of angry black men as to how they ought to construe their lives. I am not really sure that Barack Obama has earned the right to do either of those things. How the Senator’s negotiations will ultimately shake out – in terms of American attitudes about the nation’s responsibility to act so as to reduce racial inequality — is something I’m not very confident that anyone can predict. Advocates of the interest of black people have to consider what hand we’ll be left to play, should he be defeated in November. The narrative-defining moves that Obama is making now, in the heat of a political campaign and in the service of his own ambitions, must be critically examined as to what impact they will have on the deep structures of American civic obligation, for generations to come.

The deeper political perversity of Loury’s argument is that it really serves the interests of the existing political establishment made up of white Democratic triangulators and crypto-racist Republicans, who simultaneously promote and marginalize a small corps of black officeholders and established activists whose views are used as foils when white politicians need to get white voters thinking racially.

Now that is off my chest, I will admit that the real reason for highlighting Loury’s essay here is the way he makes history the center of his critique of Obama:

At bottom, what is at stake here is a fight over the American historical narrative. Obama, a self-identifying black man running for the most powerful office on earth, does threaten some aspects of the conventional ‘white’ narrative. But, he also threatens the ‘black’ narrative — and powerfully so. In effect, he wants to put an end to (transcend, move beyond, overcome…) the anger, the disappointment and the subversive critique of America that arises from the painful experience of black people in this country. Yet, the forces behind his rise are NOT grassroots-black-American in origin; they are elite-white-liberal-academic in origin. If he succeeds, there will be far fewer public megaphones for the Jesse Jacksons and Al Sharptons and Cornel Wests of this world, for sure. Many will see that as a good thing. But a great deal more may also be lost including, just to take one example, the notion that the moral legacy for today’s America of the black freedom struggle that played-out in this country during the century after emancipation from slavery – I speak here of Martin Luther King’s (and Fannie Lou Hamer’s, and W.E.B. DuBois’s, and Ida B. Wells’s and Frederick Douglass’s …) moral legacy – should find present-day expression in, among other ways, agitation on behalf of and public expression of sympathy for the dispossessed Palestinians . . . .

Speaking for myself, and as a black American man, if forced to choose, I’d rather be “on the right side of history” about such matters, . . . than to make solidarity with elites who, for the sake of political expediency, would sweep such matters under the rug (or, worse.) My fear is that, should Obama succeed with his effort to renegotiate the implicit American racial contract, then the prophetic African American voice – which is occasionally strident and necessarily a dissident, outsider’s voice – could be lost to us forever.

I think Loury has it backwards. Yet before I expatiate on that, I would be genuinely interested in what historians and historically-minded readers think about Loury’s historical argument.

March 29, 2008

Giant Cement Indian Alert

Reading a student master’s thesis draft, I learned of a crazy piece of giant historical sculpture that I have somehow missed out on seeing. As a fan of such things, though a properly appalled one, I invite anyone travelling through the Ronald Reagan Country of north central Illinois to stop by the town of Oregon, Illinois, and take in the 48-foot cement statue overlooking the Rock River. I will get there someday.

Completed by the awesomely-named sculptor Lorado Taft in 1911, the monument was entitled “The Eternal Indian” and purports to depict the Sauk war leader and popular culture hero Black Hawk, looking more generically “Indian” than Sauk or Black Hawk-like to my eyes. He is, however, very big, “the largest stand alone cement statue in the United States,” according to the local who took the modern photo at the bottom of the post. It may not be a very good likeness, but at least Black Hawk can have the satisfaction of knowing that his hated rival, the accomodationist chief Keokuk, has a much more embarrassing statue: only a fourth as high and dressed up in a highly inappropriate Plains Indian war bonnet that makes him look like the chief on F-Troop.

March 28, 2008

A Minute and a Half with Barack Obama

I have been away from the computer for a few days, but regular posting now begins again.

Via a TPM reader post I can’t seem to locate again right now, I found this very nice post from web browsing inventor Marc Andreessen, “An Hour and a Half with Barack Obama.” Obviously most of us non-millionaires would not get that long an audience, but I found the point of view interesting. Apparently a big Democratic donor, Andreessen clearly has a lot of experience being asked for money by candidates. “Most of them talk at you. Listening is not their strong suit — in fact, many of them aren’t even very good at faking it.” His hackles were up, but Obama came across “as a normal human being, with a normal interaction style, and a normal level of interest in the people he’s with and the world around him. We were able to have an actual, honest-to-God conversation, back and forth, on a number of topics.” I have had no direct Obama encounters myself, but his response to the Wright controversy struck me as a well-spoken normal person’s response to offensive remarks by an older friend or relative. He expressed his disagreement but refused to disown a loved one just to further his own career.

Naturally when talking with a computer entrepreneur Obama showed a lot of interest of new technologies like YouTube and social networking sites. Yet he also showed some actual knowledge. Not surprisingly, these new channels of communication have also been one of the most effective aspects of Obama’s campaign. Apparently, his speeches on YouTube have often gotten more viewers than the cable news channels.

The part of Andreessen’s post that resonated most strongly with me was an observation that has occurred to me too: Obama “is the first credible post-Baby Boomer presidential candidate.” This is a good thing.

The Baby Boomers are best defined as the generation that came of age during the 1960’s — whose worldview and outlook was shaped by Vietnam plus the widespread social unrest and change that peaked in the late 1960’s.

Post-Boomers are those of us, like me, who came of age in the 1970’s or 1980’s — after Vietnam, after Nixon, after the “sexual revolution” and the cultural wars of the 1960’s.

One of the reasons Senator Obama comes across as so fresh and different is that he’s the first serious presidential candidate who isn’t either from the World War II era (Reagan, Bush Sr, Dole, and even McCain, who was born in 1936) or from the Baby Boomer generation (Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, Al Gore, and George W. Bush).

He’s a post-Boomer.

Most of the Boomers I know are still fixated on the 1960’s in one way or another — generally in how they think about social change, politics, and the government.

It’s very clear when interacting with Senator Obama that he’s totally focused on the world as it has existed since after the 1960’s — as am I, and as is practically everyone I know who’s younger than 50.

Now, Andreessen may have been thinking about a “third way,” centrist approach to economics or partisanship, but the comment made think of the cultural controversies of the past month’s campaigning. Boomers and their elders do seem to be fixated on the 1960s, but they are often negatively fixated. After all, the great overarching trend of the Baby Boomers’ political adulthood (1967-on) has been a shift to the right based on voters reacting against the changes of the 1960s. The 18-year-old franchise helped bring about the 1972 Nixon landslide, and if not for Watergate, the rightward trend would have continued unimpeded through the 1990s.

Of course the real fixation is on the whole postwar generational psychodrama. There are an awful lot of Baby Boomer (and older) liberals and ex-liberals and ex-radicals who have never gotten over the switch from Kennedy-era integrationism to the angrier rhetoric and economic demands of Black Power and harbor a weird susceptibility to the Cold War logic and attendant foreign military adventures of their youth. It is a myth that most Baby Boomers actively opposed the Vietnam War, but these days the Boomers and many of their children seem to feel that opposing any war, no matter how ill-conceived, somehow dishonors the sacrifices of their World War II generation forebears.

Like Andreessen, I feel that Obama’s post-Boomer age cohort, people now in their 30s & 40s, has had a very different experience. We have lived more conservatively in many ways, what with AIDs and the drug crackdown and all, but we also tend to take the post-1960s world as a given. In our lives, there has never any point to getting steamed over the consequences of our society’s attempts at racial and gender equality. Neither have we had any reason to preen ourselves over our support of the right causes way back when, nor to resent the fact that blacks declined to quietly accept white liberal leadership in perpetuity. The seething resentment that Hillary and Bill Clinton seem to feel over someone like Barack Obama daring to challenge them is quite foreign, at least to me. Obama’s calm refusal to either back down from or fully engage them in the politics of Nixonian resentment seems like the only decent and logical course. By the same token, Obama seems unlikely to mix up belligerence with strength the way that most of the Baby Boomers and elders currently in power, and the Clintons, seem to do. No one in growing up American in the second half of the 20th century was able to escape having a head filled with tales of World War II and the 1960s, but those of us with fewer personal connections to those tales are probably better prepared to move on, which we really, really need to do.

March 25, 2008

Easter Tuesday

- Bill Hogeland makes me feel bad about praising Obama’s take on the Founders the other day, what with me being such a harsh critic of popular authors misusing the Founders. Obama did not misuse anyone, but he did, as Bill argues, present a fairly conventional post-WWII-era patriotic rendition of the founding era. Mostly. The thing is, just to have a major presidential contender acknowledge even the slavery problem is quite an advance, not on public historical discourse as seen in better schools and museums, but on the remarkably retrograde version of everything historical that is typically deployed in presidential politics.

- Robert KC Johnson takes David Greenberg’s defense of Hillary Clinton’s tactics effectively to task. Hillary’s race-baiting and general othering of a serious candidate in her own party is far worse than anything I have seen in a Democratic nomination contest during my lifetime. It is not so much Nixonian as Thurmondesque or Wallace-like.

Cheney secures his legacy: Most Evil Vice President in the History of the Universe

Not that this comes as news, but the unbelievable callousness that Dick Cheney exudes in this ABC interview is really something to behold. The slug under the video on the ABC page says it all: “Cheney on U.S. Troops: They Volunteered.” I guess this is the true soul of the “will theory of contracts” that is the essence of the GOP plutocrat philosophy: no matter how much we lied about what you were getting into, no matter how little choice you actually had about signing on, or no matter how much and how often we change the terms of your service, if you signed on a dotted line somewhere, we own you body and soul until you die or we decide to dump you.

On a more historical note, it was never more clear what the “volunteer military” really means to Cheney and like-minded neo-imperialists: mercenaries, about whose welfare they care no more than the British would have about the Hessian troops they bought back in the day. Probably less, since the Hessians were actually hired from another state/monarch who might have to answered to a some point, a problem that Cheney obviously does not regard himself as having with the American people. Others may have better analogies.

March 22, 2008

Blogging “John Adams,” Part 2: “Independence”

We finally started watching the HBO John Adams series last night. For reasons that were unclear, part 2 was available before part 1 on our cable system, but that was OK, I knew the story. It was quite watchable and not anti-educational. However, HBO’s handling of the independence saga was really not much different from the old musical 1776, only without the songs.

Paul Giamatti was appropriately uncomfortable and flop sweat-drenched as Adams, Laura Linney did not sugar-coat Abigail as much as I expected, and relative unknown Stephen Dillane made one of the better on-screen Jeffersons I have seen, hanging back in the debates, lounging when he sat, fiercely intellectualizing every remark, and brightening up when complimented on one of his gadgets. At any rate, Dillane is an improvement over Nick Nolte and the White Shadow. The great Tom Wilkinson does perfectly well as Franklin, conveying the slipperiness and calculation beneath the raconteur. Unfortunately, writer Tom Hooper has loaded the script with predictable Franklin bromides that not even Wilkinson can say aloud in a natural, non-ridiculous way. You could see “we will all hang separately” coming several minutes ahead of time. David Morse’s prosthetic nose plays George Washington, and shows more animation than the actor.

Intermittently, the second episode effectively deploys HBO Films’ trademark gritty physical realism, best seen here in a grisly smallpox inoculation sequence where we are shown the Adams’s doctor drawing matter from a dying boy’s sores and cutting it into the skin of Abigail and the children. On the other hand, the episode as a whole does not approach the sense of full immersion in a past society provided by other HBO costumers like Deadwood and Rome. No one in John Adams seems to drink heavily or swear. No one seems to have servants or slaves, though modern-pious and sometimes unlikely verbal references to the slavery issue are plentiful. The streets of Philadelphia seem to have been evacuated so the Continental Congress could meet in peace, which was very much not the case.

Geography is a big problem for the series as it always is on TV. In the HBO universe, the Adamses seem to have lived somewhere around East Cambridge, rather than Braintree on the South Shore. They can go up on a hill behind the house and see the Battle of Bunker Hill. The road from Ft. Ticonderoga to Boston runs right by their front door! Very convenient. I am including a map so the less Boston-centric can see the problem. Braintree would be off the bottom of this map.

Like the David McCullough source material, this episode was atrocious when dealing with politics or political thought. Tom Paine and Common Sense are not even mentioned, nor is there any sense of the pressure the delegates were feeling from the political radicalism that was boiling over in the streets of Philadelphia during the summer of 1776, a source of great consternation to the real Adams. (Ordinary Americans appear only in occasional scenes of silent soldiers and disease victims, and in a nice polite crowd that hears the Declaration read at the end.) Here the speech Adams gives in reply to John Dickinson during the final independence debate comes out of nowhere and sounds more like Paine than Adams, proposing a national republic and extolling revolution in a way that would have had the most of the delegates fleeing back home or to the British if anyone one had actually said that kind of stuff on the floor of the Continental Congress. The real speech, while not recorded, seems to have been much more practical and nothing the delegates had not heard many times before.

But it feels so good . . .

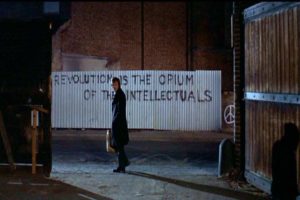

I was having fun last night after getting some new DVD software that finally allowed me to capture stills from DVDs like all the other kids. This one is from a favorite old movie I just finally got to see, Lindsay Anderson’s O Lucky Man! (1973).

March 21, 2008

A “Double Standard” on Racism?

Commenter Mike V seemed to be replying to the wrong post, so I will reply here. First of all, let’s repeat once again that in providing some context for Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s sermons, Barack Obama was giving reasons, not excuses. And would Mike or anyone else really want a president who was the sort of person who was in the habit of angrily walking out of church whenever they heard something from the pulpit they didn’t like, or thought might hurt them politically? No, I imagine that would be an entirely different Fox News flap.

Whatever unpleasant things Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Jeremiah Wright or any other prominent black preacher may have said or their critics may have heard them say about white people or “America,” it is not a “double standard” to decry racism and also show hostility to those people (or institutions or cultures or whatever) they believe to be racist. That is more like consistency, isn’t it? The same could said for Wright’s most quoted sermon, where he essentially argues, in what I thought was fairly orthodox Christian fashion, that the United States is like any other human institution, and cannot claim to be sinless or blameless before God.

It is also not a “double standard” that whites, especially whites holding important public trusts or enjoying access to huge audiences, are nowadays occasionally held responsible when they make racist remarks or engage in racist behavior. That is just a standard, albeit one that whites managed to shirk until the recent past. Up until the 1960s (or much later in many settings), public racism was a prerogative of the unjust power white men possessed over everyone else in American society. That’s over, or at least it ought to be, and the fact that people like Don Imus once got away with such misbehavior exculpates exactly nothing as far as their present behavior goes. When angry white guys moan about “political correctness” or “reverse racism,” what they are really mourning is the loss of an unjust advantage guys like them once had. Too bad.

Now, a little more context for Rev. Wright’s type of rhetoric, which has the white political and media world’s shorts in such a bundle. It would have been very convenient for whites if African Americans, after two centuries of slavery, legal discrimination, and violent repression, followed by another century of just the last two, had all been able to eternally abstain from negative feelings about all that had come before (and the continuing aftereffects). But that’s not human nature, is it? Nor was it, or is it, reasonable or just to ask that blacks avoid natural human feelings that they were once absolutely forbidden to express in public.

There is a powerful expression of that situation in the lyrics of “The Love You Save (May Be Your Own)” by the great Joe Tex:

I’ve been pushed around

I’ve been lost and found

I’ve been given ’til sundown

to get out of town

I’ve been taken outside

and I’ve been brutalized

and I’ve had to always be the one to smile and apologize

While whites may not like to hear it, harsh rhetoric like Jeremiah Wright’s, in his context, is a completely different thing, than nasty racial humor from a Don Imus, in his. The former was expressing, too intensely, perhaps, the real feelings of many in his audience based on real social and historical situations. The latter was just powerful man making sport of the less powerful because he thought he could, and that it might help make him some money. The former was an African American pastor speaking to his own largely African American church. The latter was a national radio and television personality speaking to heterogeneous millions over the airwaves, and whatever we are supposed to call cable TV and the Internet.

March 20, 2008

Hillary Clinton’s “Experience”: A Double-Edged Sword

Hillary Clinton’s opponents really need to hold her to her claims about her experience, and make sure she owns up to the Clinton administration policies, and other stuff, that she really was instrumental in putting forward. For instance, we have some new evidence for what I said earlier about NAFTA:

First lady records show Clinton promoted NAFTA

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton now argues that the North American Free Trade Agreement needs to be renegotiated, but newly released records showed Wednesday she promoted its passage.

The National Archives and the Clinton presidential library jointly released more than 11,000 pages of Clinton’s daily schedule as first lady from 1993 to 2001.

The release came in response to charges that she is overly secretive, and also allowed her campaign to promote her argument that she gained valuable White House experience during her years as first lady.

Clinton and Obama are battling to win Pennsylvania on April 22, the next contest in a closely fought campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination to face Republican John McCain in the November election.

The documents clearly indicated that Clinton had a powerful role at the White House, frequently meeting foreign leaders and presiding over meetings. . . .

Read the rest here.

March 19, 2008

Obama as Historian: The speech on race

There are many things one could say about Barack Obama’s speech on race yesterday. Something coming out a presidential candidate’s mouth that would be worth hearing or reading even if had no political significance? Check. A political masterstroke that will make it very difficult for Clinton or McCain or the media to continue or resume using the sort of Atwater-Morris veiled racist tactics we have seen over the past month? Check. A contributor to our current public discourse actually putting a momentary campaign flap into historical perspective, turning it into something that illuminates the issues of our times rather than obscuring them? Double-check.

To begin with a topic close to the heart of this blog, Obama’s discussion of the relationship between slavery and the Constitution was more balanced and insightful than most of us historians could produce:

“We the people, in order to form a more perfect union.”

Two hundred and twenty one years ago, in a hall that still stands across the street, a group of men gathered and, with these simple words, launched America’s improbable experiment in democracy. Farmers and scholars; statesmen and patriots who had traveled across an ocean to escape tyranny and persecution finally made real their declaration of independence at a Philadelphia convention that lasted through the spring of 1787.

The document they produced was eventually signed but ultimately unfinished. It was stained by this nation’s original sin of slavery, a question that divided the colonies and brought the convention to a stalemate until the founders chose to allow the slave trade to continue for at least twenty more years, and to leave any final resolution to future generations.

Of course, the answer to the slavery question was already embedded within our Constitution – a Constitution that had at is very core the ideal of equal citizenship under the law; a Constitution that promised its people liberty, and justice, and a union that could be and should be perfected over time.

And yet words on a parchment would not be enough to deliver slaves from bondage, or provide men and women of every color and creed their full rights and obligations as citizens of the United States. What would be needed were Americans in successive generations who were willing to do their part – through protests and struggle, on the streets and in the courts, through a civil war and civil disobedience and always at great risk – to narrow that gap between the promise of our ideals and the reality of their time.

Then there were Obama’s now much-quoted remarks addressing all the hand-wringing and contrived outrage over some filmed sermons by his pastor that went beyond the circumscribed limits of what the media consider reasonable, legitimate discourse. Obama’s message was a sincere and humane one: you have to understand where the man was coming from and the different ways that different groups in our society have of expressing themselves.

This is the reality in which Reverend Wright and other African-Americans of his generation grew up. They came of age in the late fifties and early sixties, a time when segregation was still the law of the land and opportunity was systematically constricted. What’s remarkable is not how many failed in the face of discrimination, but rather how many men and women overcame the odds; how many were able to make a way out of no way for those like me who would come after them.

But for all those who scratched and clawed their way to get a piece of the American Dream, there were many who didn’t make it – those who were ultimately defeated, in one way or another, by discrimination. That legacy of defeat was passed on to future generations – those young men and increasingly young women who we see standing on street corners or languishing in our prisons, without hope or prospects for the future. Even for those blacks who did make it, questions of race, and racism, continue to define their worldview in fundamental ways. For the men and women of Reverend Wright’s generation, the memories of humiliation and doubt and fear have not gone away; nor has the anger and the bitterness of those years. That anger may not get expressed in public, in front of white co-workers or white friends. But it does find voice in the barbershop or around the kitchen table. At times, that anger is exploited by politicians, to gin up votes along racial lines, or to make up for a politician’s own failings.

And occasionally it finds voice in the church on Sunday morning, in the pulpit and in the pews. The fact that so many people are surprised to hear that anger in some of Reverend Wright’s sermons simply reminds us of the old truism that the most segregated hour in American life occurs on Sunday morning. That anger is not always productive; indeed, all too often it distracts attention from solving real problems; it keeps us from squarely facing our own complicity in our condition, and prevents the African-American community from forging the alliances it needs to bring about real change. But the anger is real; it is powerful; and to simply wish it away, to condemn it without understanding its roots, only serves to widen the chasm of misunderstanding that exists between the races.

To paraphrase, a favorite film of ours, Grosse Pointe Blank, history wasn’t an excuse for Rev. Wright’s statements, but it was a reason.

Obama was equally perceptive on the roots of white working-class racial anger, linking attitudes among “white ethnics” in particular to the lingering effects of the immigrant experience:

In fact, a similar anger exists within segments of the white community. Most working- and middle-class white Americans don’t feel that they have been particularly privileged by their race. Their experience is the immigrant experience – as far as they’re concerned, no one’s handed them anything, they’ve built it from scratch. They’ve worked hard all their lives, many times only to see their jobs shipped overseas or their pension dumped after a lifetime of labor. They are anxious about their futures, and feel their dreams slipping away; in an era of stagnant wages and global competition, opportunity comes to be seen as a zero sum game, in which your dreams come at my expense. So when they are told to bus their children to a school across town; when they hear that an African American is getting an advantage in landing a good job or a spot in a good college because of an injustice that they themselves never committed; when they’re told that their fears about crime in urban neighborhoods are somehow prejudiced, resentment builds over time.

Obama’s expression of the immigrant approach to race was so good, it raises a possibility that I hope Obama can articulate in the Pennsylvania campaign. This possibility is that an African American leader is uniquely positioned to express and deal with the social anxieties of all Americans. “Whiteness” in this country more or less requires adopting the stance that one has transcended all purely social limitations and competes on an equal footing with all other Americans. This is an illusion for almost everyone, but it is not one that most African Americans have ever had the luxury of indulging in, so African American politicians are under no obligations to genuflect to it. That provides some freedom of rhetoric and action that few white politicians enjoy. Obama already used that freedom when opposed the war at a time when even most Democrats felt irresistible pressure to go along.

Matt Yglesias seems surprised that conservatives were not mollified by Obama’s contextualization of racial anger. I was not surprised. Social context and historical perspective are the deadly enemies of current right-wing thought, the intellectual survival of which depends on maintaining simple, dualistic notions of good and evil and a view of the universe in which only private moral choices matter. Serious historical thought is a solvent for attitudes of this type, so conservatives no like.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.3 (April, 2008).

Jeffrey L. Pasley is associate professor of history at the University of Missouri and the author of “The Tyranny of Printers”: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (2001), along with numerous articles and book chapters, most recently the entry on Philip Freneau in Greil Marcus’s forthcoming New Literary History of America. He is currently completing a book on the presidential election of 1796 for the University Press of Kansas and also writes the blog Publick Occurrences 2.0 for some Website called Common-place.