The case for brushing up your Shakespeare

History has a kind of conscious life in the institutions, ideologies, movements, and forces that seem to constitute the daylight workings of society; but it has a kind of nocturnal life as well—a dream world ruled by the various alchemies of metaphor and symbol, where the boundaries between one institution and another with which it is constantly at war, between an idea and its contrary, swim about in a kind of cultural ectoplasm where forms change places with one another, sending the spirit of one into the body of its sworn antagonist, bringing the dead back to life in new incarnations.

—Robert Cantwell, When We Were Good: The Folk Revival (Cambridge, Mass., 1996)

Last year, over spring break, I attended the annual meeting of the Shakespeare Association of America (SAA), which happened to be held in Bermuda. For a historian accustomed to events like the AHA, OAH, or the Omohundro Institute’s annual conferences, let me tell you, SAA in Bermuda was an eye-opener. First of all, the Shakespeareans know how to party. Their receptions were lavish—one night, it was a buffet dinner with open bar in a swank Bermuda hotel, with a steel drum band and dancing. Why can’t we historians live like this?

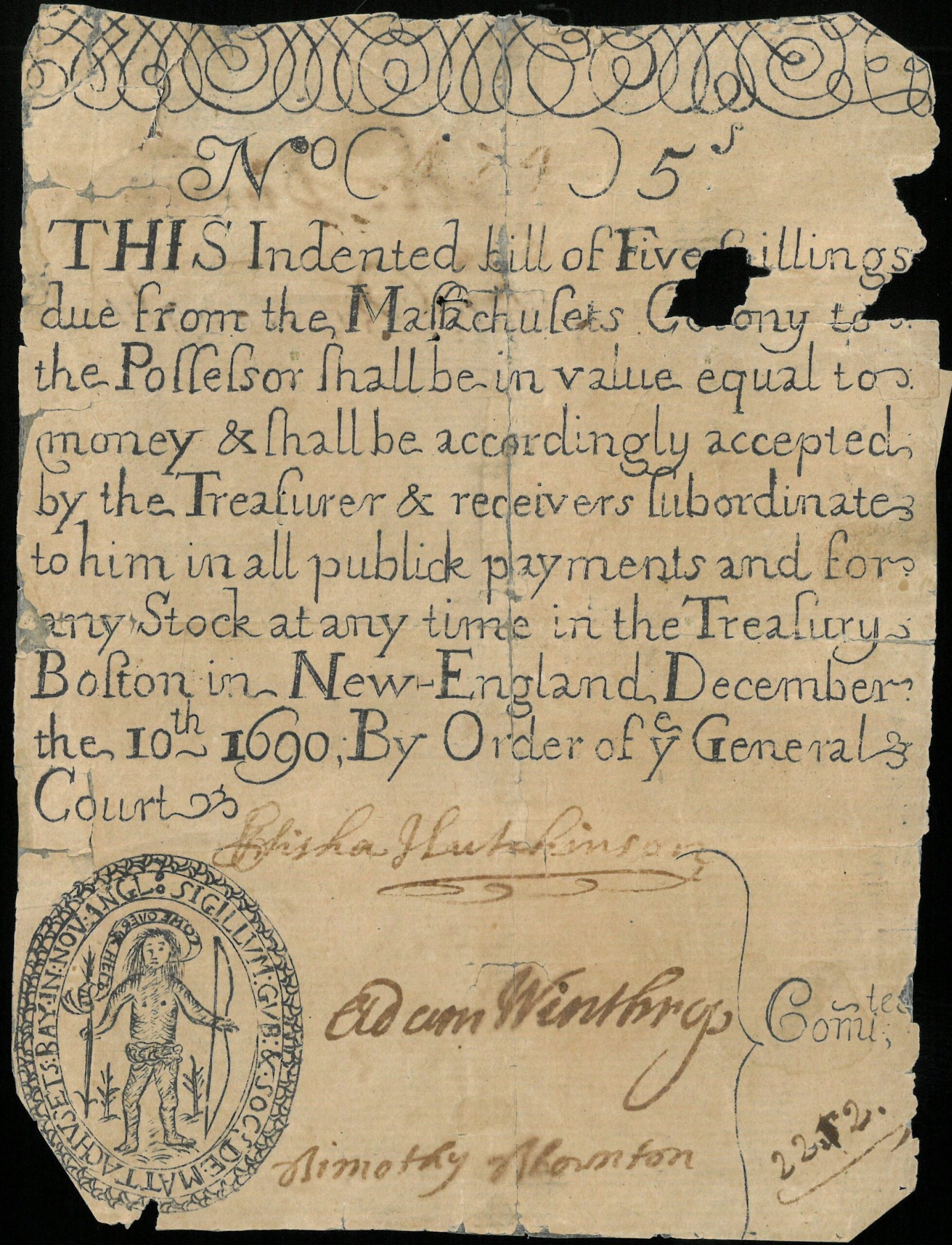

But the conference was revealing in another way, or at least it confirmed a suspicion that had been growing on me for some time. As I listened with interest to the remarkable range of panels and papers devoted to Shakespeare and his world, it seemed ever clearer to me that Shakespeare is the major figure in the “nocturnal life,” the “dream world,” of early American history, if I may borrow Robert Cantwell’s compelling image. For a variety of somewhat surprising reasons, I have been exposed to more Shakespeare over the past dozen years than I might have anticipated. In addition to the Bermuda meeting, during which I forced myself to pay close attention to The Merchant of Venice in order to think about the problem of money in the Atlantic economy, I have also had the pleasure of watching my children, ages twelve and ten, appear in productions of The Tempest and Hamlet, and these experiences have fed a minor Shakespeare obsession on their part. Abetted by the theater opportunities of a smallish college town, they have attended at least a dozen full-scale productions of various Shakespeare plays—comedy, history, and tragedy—and seen versions of many others on video and DVD. For a historian of early America, especially one who has so far specialized in Puritan New England, all this Shakespeare has had a salutary effect.

The process of getting up to speed on the Puritans, to the point of feeling even vaguely comfortable writing about them, can be overwhelming. It requires a deep and painful immersion experience. The primary sources are voluminous, dense, and sometimes impenetrable. Consider, for example, what Thomas Shepard once wrote to John Cotton:

I doe also grant that many professors do cozen themselves with inward legall righteousness, either wrought in them by vertue of the spirit of bondage or fetcht from Christ himself, & take legall acts & dispositions as sure signes and markes of being in Christ; but yet I still desire to know of yow whether this is the same righteousnes that Adam had for essence, differing from it only in degree, & whether tis the same holines & righteousnes that true beleeuers haue differing one from another only in the efficient, faith working the one, the law and the spirit of bondage woorking the other.

My point exactly. I’ve been cozening myself that way for years.

The modern scholarship is pretty voluminous and dense as well, and although few contemporary scholars can match Shepard and his pals for opacity, it’s not for lack of effort. This instance falls readily to hand:

While the preparationists rarely described consummated union, the Cambridge Brethren frequently expressed confidence in adoption as a past event. It is not the stages before adoption, but the life of the regenerate Christian afterwards, that they preach. But precisely how this application of mercy, by which sinners are made children, is accomplished must be understood within the framework of covenantal doctrine. If theologians must calculate the equation of sin and love, God’s covenantal promise is the term that mediates between them.

Indeed. So, as I was saying, the long hard road to understanding the Puritans can have an unintended effect on one’s literary world and mental universe. It can leave one knowing little else or at least knowing little else with anything like the mastery required to know the Puritans.

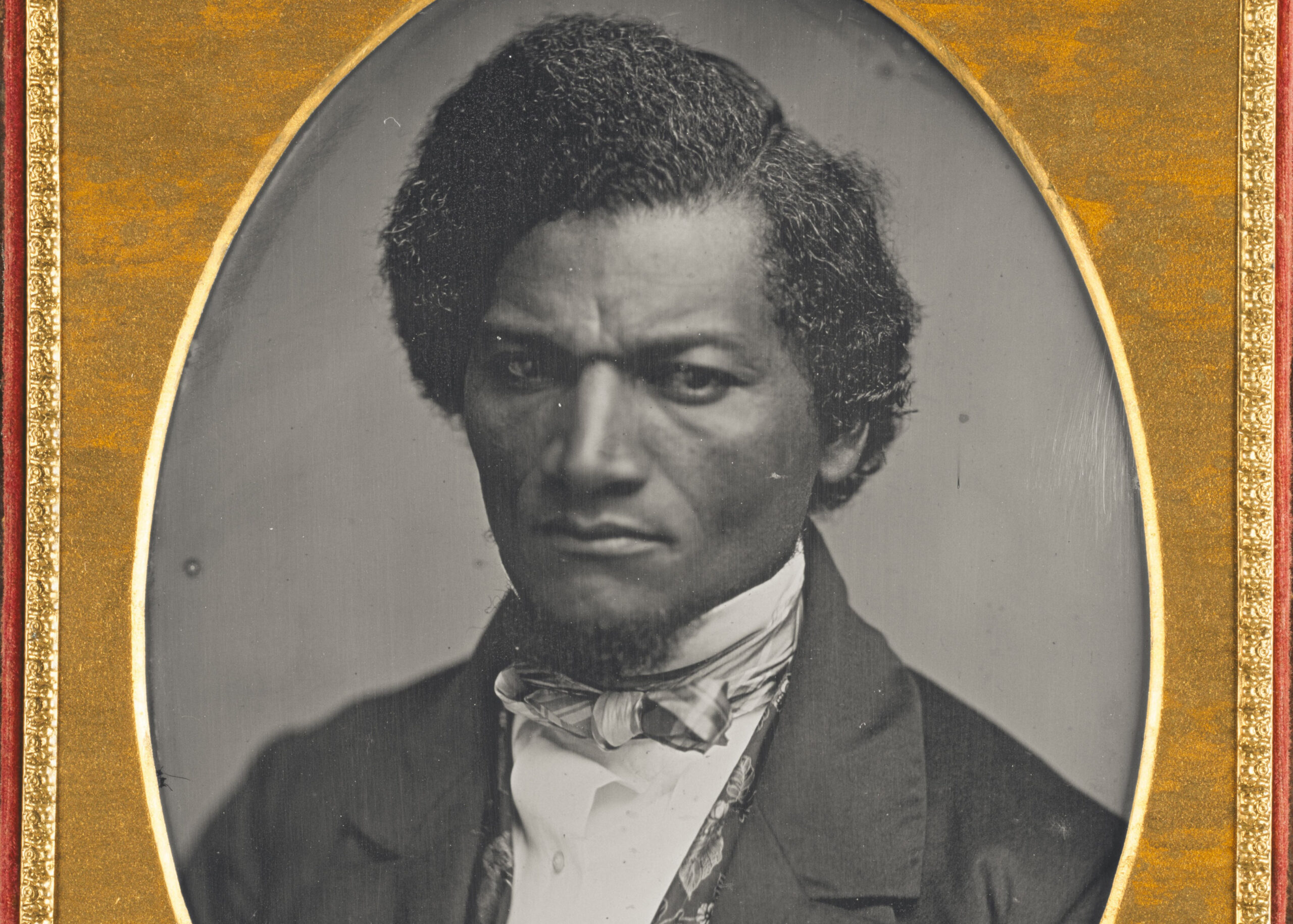

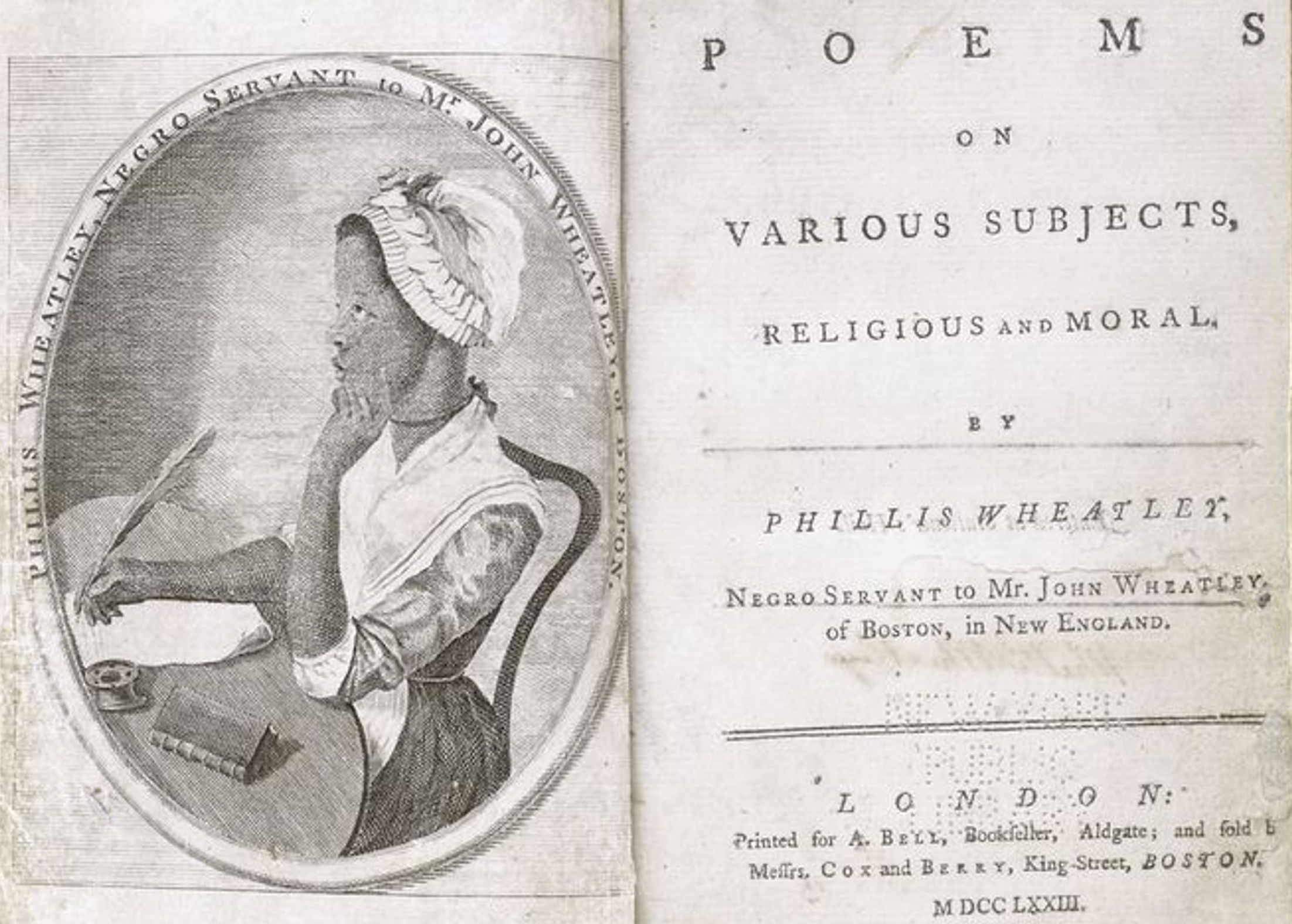

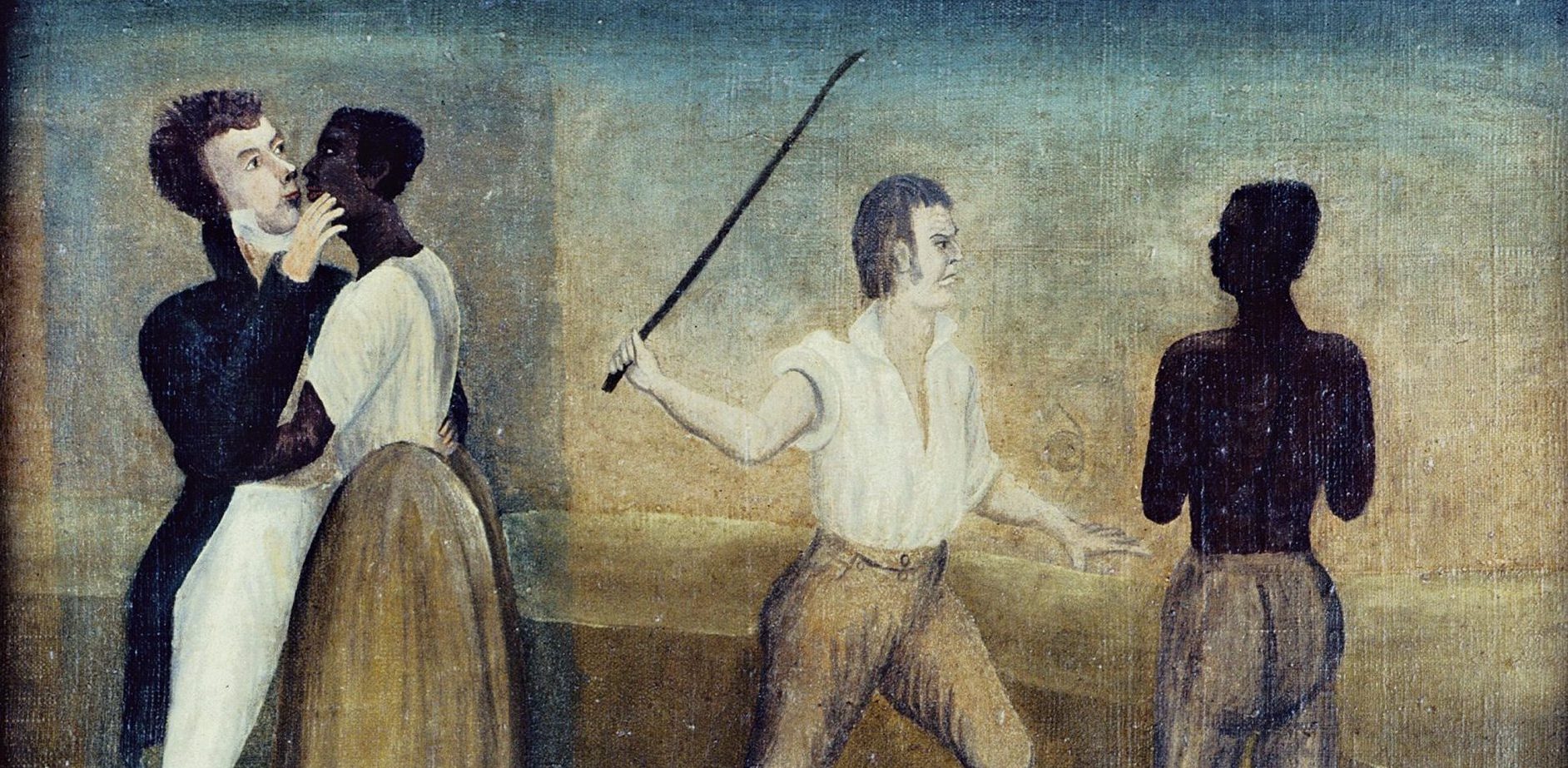

The cost of our narrow studies is not just one of literary breadth. It is also one of understanding. We who continue to ignore the wider world of which the Puritans were a part and for which Shakespeare stands as a colossal exemplar, do so at our own peril. Of course, many of us use snatches of The Tempest in the opening weeks of our survey courses—its island setting, shipwreck, and utopian dreams all appropriately reminiscent of the ill-fated Somers expedition to Bermuda. But then Shakespeare, like the island paradise dreamed up by the courtier Gonzago, fades away from our syllabi in the harsh reality of New World colonies, to be seen or heard again no more. We turn our attention instead to servants and slaves, the symbolic descendants of the brutalized Caliban, left behind in island exile when Prospero and his courtly attendants have returned to their civilized European abode.

Shakespeare’s absence from our syllabi seems appropriate, if we’re only examining the “daylight workings of society,” because the Bard was missing from the colonial scene. Theater was banned in Boston, the only place with the cultural wherewithal to have staged a play in the seventeenth century. For people to stand on a stage and pretend that false was true was to give public lessons in lying. It undermined the sacred word, the foundation of human salvation and moral order, and Puritans would have none of it. When a proposal was made that a play be performed in Boston’s Town House, recently rebuilt at public expense to house the colony’s government and superior court as well as its merchants’ shops, Samuel Sewall objected, “Our Town House was built at great Cost and charge for the sake of very serious and important Business. Let it not be abused with Dances or other Scenical divertisements. Let not Christian Boston goe beyond Heathen Rome in the practice of shamefull Vanities.” The ban was not lifted until the 1790s.

But Shakespeare and the world he represents—the color, sound, and movement of theater; the churning and vibrant life of London’s streets, taverns, and shops; the splendor of the court; the rich variety of literary genres and subjects that flourished in Elizabethan and Jacobean England; the continental, Mediterranean, and classical settings in so many of the plays; perhaps even Shakespeare’s purported recusant Roman Catholicism; the longing for a lost world of ritual, religious mystery, and pan-European unity—all these linger in the background of early America. They constitute a cultural shadow, the phantom missing limb from the body of experience that shaped England’s colonies, even, or especially, New England’s Puritan settlements.

In the simplest terms, without the bawdy world of Falstaff and Prince Hal and of Shakespeare’s jesters, beadles, and gravediggers or the hovering evil of murderous kings, corrupt priests, scheming witches, and ungrateful daughters there would have been nothing for those dissenting Puritans to dissent from. The godly needed the rude, the venal, the vulgar, ignorant, and irreverent and framed their own identity against them. “Puritan” is the word with which the profane mocked the godly, a fact that emerges most clearly in Twelfth Night, where the Bard’s only ostensibly Puritan character takes the stage in the person of Malvolio.

Mal Volio=Bad Will. The play on words is no coincidence, for Malvolio is not only full of ill will toward all humanity but also stands as Will Shakespeare’s alter ego and distorted mirror image—he is Bad Will (and the play’s subtitle, after all, is “What You Will”). Malvolio has nothing but contempt for men and women of all classes, from the drunken and lecherous Sir Toby Belch to the witty and world-wise fool, Feste. But when it comes to the Countess Olivia, for whom he works as steward and whose title, estate, power, and personal charms he covets, Malvolio plays the sycophantic schemer, longing to get his hands on what he wants: to wed Olivia and become Count Malvolio. His desires are his downfall. Maria, the Countess’s maid, schemes with Sir Toby and the fool to drive Malvolio to distraction and ruin, undermining him with his own ambitions and conceits. They forge a false letter from the Countess, dropping it in Malvolio’s path, which leads him to believe the Countess loves him and encourages him to abandon his sober Puritan’s garb and mien for an outlandish costume of “yellow stockings, cross-gartered,” and incessant, excessive smiling. A smiling Puritan in yellow stockings? Madness.

As Stephen Greenblatt’s recent Will in the World points out, when Shakespeare mocks Malvolio, or Bad Will, he mocks his own pretensions, his personal desire for nobility, flattery, and worldly recognition. In his spare hours, the Bard pursued a legend that the Shakespeares were an armigerous family, deserving of a coat of arms, and in the end he got one. But in the character of Malvolio, Shakespeare also mocks Puritans in general and, incidentally, nails an often forgotten quality about New England’s, and America’s, founding settlers: Malvolio, as a Puritan, is prone to make too much of words, to take them too literally. And in a jab at the Puritan opposition to theater, he also puts on a mask, the false face of grave sobriety, to disguise the true intent of his heart. But more specifically, like Malvolio, the Puritan leaders of Massachusetts were ambitious men who found their way in the world by fawning upon sympathetic aristocrats.

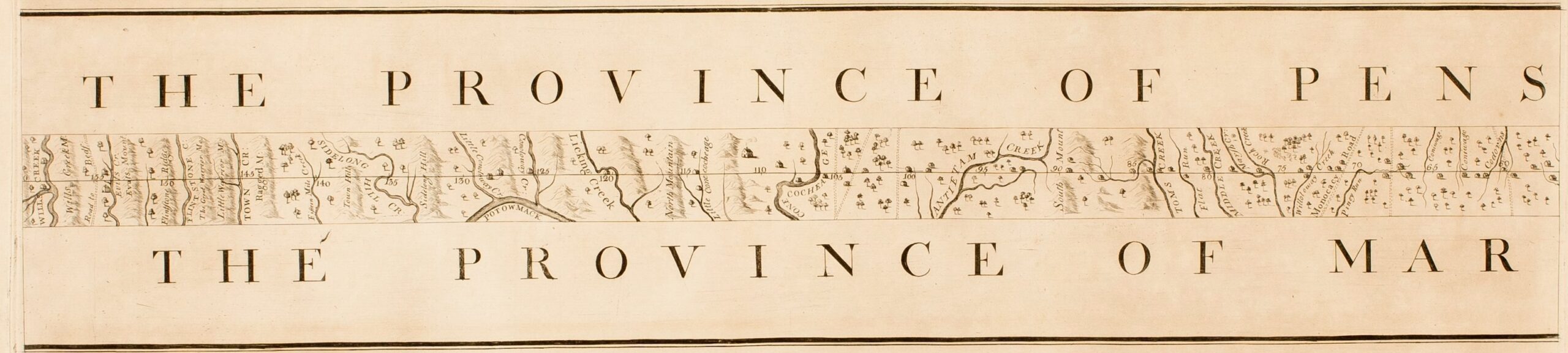

Consider Thomas Dudley, the sometime governor of first-generation Massachusetts, father of Anne Bradstreet, founder of Cambridge, early supporter of Harvard College, and rival of John Winthrop. Dudley, like Malvolio, was the steward to a great household, the Earl of Lincoln’s. One of our best sources for the early years of Massachusetts settlement is a letter Dudley wrote to the Countess of Lincoln. Other leading lights of the Massachusetts Bay Company, like Isaac Johnson and John Humfrey, gained prominence through fortunate marriages to the Earl of Lincoln’s daughters. The Arbella, the famous flagship of the first fleet, was named for the Lady Arbella, the earl’s daughter who married Isaac Johnson.

Needless to say, in the harsh days of religious persecution that engulfed England in the decades before the Civil War, many Puritans needed the protection offered by powerful noblemen and women. As they left England for New World exile, the middling, quasi-republican form of self-government that Winthrop and company created in Massachusetts deterred Puritan nobility like the Earl of Warwick and Lord Saye and Sele from joining the New England venture. Nevertheless, the relative absence of true aristocrats from the New England scene in the seventeenth century should not overshadow the importance of their patronage in the colony’s founding. Without the aristocrats’ funding, their political machinations and protection, and their ability to foster and encourage the clergymen and educated lay people who sustained the enterprise, Massachusetts would have remained a vaporous dream.

Although often obscured, the presence of Shakespeare and the world he represents as the lurking alter ego of Puritan New England has never been entirely forgotten. To the extent that Shakespeare’s England had a presence in early New England, it was represented by Thomas Morton, who started a renegade settlement between Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay and named it Merrymount, complete with maypole dances, drunken debauchery, and risky arms trading. Falstaff and Toby Belch would have been right at home. Despite his suppression and deportation by Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay authorities, Morton managed to publish the wildly satirical, though scarcely coherent, New English Canaan, which described his picaresque New England adventures and his suffering at the hands of these American Malvolios.

In the early nineteenth century, at a time when many New Englanders were leaving their Calvinist religious heritage behind, Morton’s legacy was resurrected by Nathaniel Hawthorne in his story “The Maypole of Merrymount” (1836) and by John Lothrop Motley’s novel Merry Mount (1849). These works were part of a growing tendency for American authors to demonize their Puritan ancestors, a trend that became stronger over time and reached its height at the turn of the twentieth century.

By then, Harvard College, founded as a center of Puritan learning, was attempting to transform itself from a provincial college to a world-renowned university, with Ph.D. programs, professional schools, scientific laboratories, and an open curriculum receptive to the latest and best from the globe’s scholars. Given these grand and cosmopolitan ambitions, many Harvard leaders and alumni were more than a little embarrassed by the origins of their alma mater. This was perhaps the historical low point in the Puritans’ public reputation, several decades before the heroic efforts of the scholars Morison, Miller, and Murdock to resuscitate the New England mind in all its vanished glory.

Ambition, envy, dismay at one’s origins, and the potential for embarrassment—these are fertile ground for fantasy and self-delusion. Witness Malvolio. And on this ground there grew a rich fantasy indeed, a persistent effort to link John Harvard, the college’s early benefactor, with none other than the Puritans’ sworn antagonist, William Shakespeare. To be fair, a slim reed of evidence exists for a speculative link between John Harvard and the Bard. Shakespeare was considerably older than John Harvard, who was born in 1607 when Shakespeare was fully at the height of his powers and producing masterful plays like Othello, Macbeth, and King Lear. But the future college benefactor was in fact born in Southwark, just across the Thames from the City of London, at the home of his father, Robert Harvard, who owned a butcher shop not far from Shakespeare’s Globe Theater. And what’s more, John Harvard’s mother, Katherine Rogers, was born and raised in Shakespeare’s own birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Slim evidence and completely circumstantial, but for those eager and willing to believe, like Malvolio reading the forged love letter, this was evidence enough to concoct a story that John Harvard’s parents must have been introduced to each other by the Bard himself, making Shakespeare, in effect, the godfather of Harvard. Never mind the much more plausible explanation that since Katherine Rogers was the daughter of a cattle dealer and Robert Harvard was a butcher, the cause of their meeting was probably meat. In 1907, Henry C. Shelley produced a book-length biography, John Harvard and His Times(necessarily heavy on the “and his times” because the sum of all known information on John Harvard fits easily on a note card), which argued conclusively for Shakespeare’s matchmaking role in the history of Harvard.

Five years later, a still more enterprising scholar named Alfred Rodway drew upon deep and profound research in ancient English heraldry (those coats of arms again!) and etymology to demonstrate that William Shakespeare and John Harvard were both descendants of the same sixth-century Danish invader of the East Anglian coast. The results were published in a book called The Sword of Harvaard (1912). At a time when most Ph.D. dissertations in early American history still supported Herbert Baxter Adams’s “germ theory” of history (i.e., that English colonists carried the genetic “seed” of republican self-government to America, originally cultivated by the Angles and Saxons in the forests of northern Europe), Rodway’s conclusions were not all that far fetched. Through breeding and through marriage, it was now obvious that Harvard’s ostensibly Puritan roots were but an aberration—the institution had been Shakespearean and Shakespeare’s doing, all along.

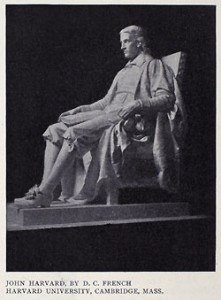

Perhaps this collective fantasy explains the curious appearance of the famous statue of John Harvard, produced by the sculptor Daniel Chester French, dedicated in 1884 and still standing in front of University Hall at the center of the Harvard campus. It is commonly called the “Statue of the Three Lies” because inscribed on its base are a trio of falsehoods. It claims that the statue is of John Harvard, when there are no known images of what the benefactor looked like—a contemporary student sat as French’s model. It claims that John Harvard was the founder, when the college was actually founded by an act of the Massachusetts government and named for John Harvard only after his posthumous gift. And it gives the founding year as 1638, which was actually the year John Harvard died and left his estate to the college, founded two years earlier in 1636.

But in choosing the features with which to adorn his student model, Daniel Chester French added an additional, seldom noticed falsehood, prompted, I suggest, by the power of the Shakespeare fantasy. For if there is one visible feature that the Puritans of John Harvard’s day were known for, it was their close-cropped haircut (the distinctive do is why the Puritans gained the nickname of “Roundheads” during the English Civil Wars). But French’s John Harvard, with his long flowing locks and pencil-thin, delicate mustache, is no Roundhead—he’s a Cavalier, through and through. Despite their best efforts, the Puritan founders of Harvard College could not wholly suppress their alter ego, the part of their culture they hoped to leave behind, and the spirit of Shakespeare reappeared in the bronze body of one of his sworn antagonists. We might do well to attend to this sort of alchemy, the nocturnal workings of history, and see what we get by restoring more of Shakespeare and his world to our understanding of early America.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.1 (October, 2006).

Mark Peterson teaches in the history department at the University of Iowa. He is the author of The Price of Redemption: The Spiritual Economy of Puritan New England (Stanford, 1997) and is at work on a book on Boston in the Atlantic World.