Reframing Abolition: African Americans and Calls to End Slavery in Revolutionary Massachusetts

One of the central arguments of To Plead Their Own Cause is to reframe the chronology of the abolition movement away from the traditional focus of historians on the antebellum era. How does that chronological shift change our understanding of the process of abolition?

Exploring abolitionism from the revolutionary era to the Civil War demonstrates that the American antislavery movement was nearly a century in the making, rather than thirty or forty years, and that the key strategies and tactics of the supposedly more radical abolitionists of the 1830s were developed by black activists during the 1770s. Many scholars have separated American abolitionism into two movements, a pre-1830 one that essentially failed, given the massive growth of slavery in the nation, and a post-1830 one that eventually succeeded. The former movement is often seen as less radical, characterized by gradualism, and led by whites, while the latter is portrayed as an interracial and radical affair. I argue that radical, interracial abolitionism began among blacks in Massachusetts during the 1770s and their tactics and ideology continued to play an important role in the movement through the antebellum period.

The shift I propose changes our understanding of American abolitionism in two primary ways. First, it shows a different religious foundation for abolitionism than what we get when we focus primarily on the antebellum era. By locating the origins of the antislavery movement in the 1830s, as most of the scholarship has done, abolitionism is unavoidably tied to the major religious development of that time, namely the Second Great Awakening and the rise of evangelical religion. In this formulation, abolitionism stems from the perfectionist theology of figures such as Charles Grandison Finney and the rise of a “Benevolent Empire,” or a series of measures aimed at reforming American society, including prison reform, the temperance movement, educational reform, etc. These developments in American religious thought and practice did of course influence the antislavery movement in profound ways, but I argue that they did not initiate the antislavery movement. Instead, they took the movement in new directions and gained more adherents for the cause. Exploring abolitionism in colonial and revolutionary America demonstrates the strong influence of the First Great Awakening on the origins of the movement. As opposed to its nineteenth-century counterpart, this revival was steeped more in Calvinism than Arminianism and that theology had important implications for both black thought and blacks’ place within the New England legal system.

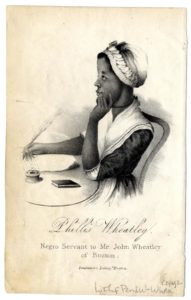

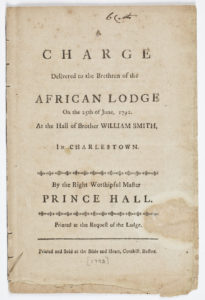

Second, shifting the chronology of abolitionism’s origins to the revolutionary period demonstrates the prominence of republicanism in antislavery thought. John Saillant’s excellent biography of Lemuel Haynes demonstrates the centrality of republicanism in his worldview, and I argue that such was also the case among black abolitionists in Massachusetts. Core features of republicanism that individuals such as Phillis Wheatley and Prince Hall spoke to included equality, representative government, and a willingness to sacrifice individual interests for the good of the nation. This last point coincided well with Puritan religious thought and the black jeremiad.

You emphasize in the book the role of the genre of the “black jeremiad” as a means for African Americans to argue against slavery. Can you explain the distinct characteristics of the genre in the context of abolition?

The black jeremiad was an adaptation by African American thinkers and activists of a popular sermonic form that Congregational ministers had employed in New England dating back to the mid-seventeenth century. As Sacvan Bercovitch notes in his seminal work The American Jeremiad, Puritan ministers starting in the 1660s began to exhort their parishioners to return to what was perceived as the more godly ways of an earlier generation. This was partially a response to the Half-Way Covenant of 1662, which allowed the children of church members to be baptized even if they had not experienced conversion, as well as changing demographic and economic factors resulting from heavy migration to the colonies.

For Puritan ministers, the jeremiad became an important method of social critique and means of effecting religious enthusiasm and regeneration among their parishioners. It was a way to show the critical links, in the eyes of ministers, between individual behavior and communal success. So for ministers such as Increase Mather, sleeping during church services or imbibing too much alcohol were not merely evidence of individual depravity but signs that the godly experiment was in danger of failing. If people persisted in their sinful ways, ministers argued, then God would take it as a breach of their covenant with him and would punish the colonists with famine, disease, drought, and attacks by their enemies.

African Americans, steeped as they were in Puritan thought, recognized the utility of this sermonic form and expanded it to meet their own ends. In their view, a major shortcoming of jeremiads preached by Congregational ministers was that they often neglected to critique what blacks saw to be the most heinous sin of all, the institution of slavery. Thus, black thinkers such as Caesar Sarter, Lemuel Haynes, Prince Hall, and others developed their own form of the jeremiad that included racial inequality and slavery as sins that would have just as detrimental an effect on New England society as alcoholism, thievery, etc. If New Englanders continued to persist in the sin of slavery, they argued, then God would take this as a breach of their covenant with him and punish them appropriately. Caesar Sarter’s abolitionist essay, “Address, To Those Who are Advocates for Holding the Africans in Slavery,” asked the colonists “why, in the name of Heaven, will you suffer such a gross violation of that rule by which your conduct must be tried, in that day, in which you must be held accountable for all your actions, to, that impartial Judge, who hears the groans of the oppressed and who will sooner or later, avenge them of their oppressors!” Phillis Wheatley used more subtle language but essentially argued the same thing in her 1774 letter to the Native American minister Samson Occom, where she noted that the spirit of freedom in blacks “is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance,” and that God would “get him honor,” or be avenged, upon the colonists for enslaving Africans. Four years later, she developed her critique and asked, in her poem “On the Death of General Wooster,” how “presumptuous shall we hope to find/Divine acceptance with th’ Almighty mind—/While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace/And hold in bondage Afric’s blameless race?” For Wheatley, Sarter, and other black abolitionists, then, success in the American Revolution absolutely depended on taking steps toward abolition, and the jeremiad became a powerful tool for articulating that argument.

The book focuses on Massachusetts, where Calvinism was a dominant (perhaps even hegemonic) religious ideology. What influence did that strain of Protestant thought have on the way in which your historical actors saw slavery and freedom?

Massachusetts Puritans’ adherence to Calvinism had very significant implications for black life in the colony. Ministers such as Solomon Stoddard and Cotton Mather argued for the incorporation of slaves into the family and Congregational churches because of their belief in Calvinism. If all men and women are predestined to go to heaven or hell and nobody on Earth knew who was going where (a central belief of Calvinists), then how could anyone say with certainty that African slaves were not among the Elect? Stoddard, Mather, and other ministers argued that you could not say Africans were damned and thus they should have the same religious upbringing as whites. Mather articulated this belief in his important pamphlet The Negro Christianized and put his belief into practice by operating a Sunday school for blacks in his church for approximately two decades. This became an important tool for Boston slaves in building communal ties, gaining literacy, and learning some of the major tenets of Calvinist theology.

Calvinism also had important implications for Africans who accepted its tenets when it came to their views on slavery and freedom. Just as Puritan ministers argued that Africans were capable of being saved, so too did blacks argue for their spiritual equality with whites. In her famous poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” Phillis Wheatley noted that “Negros, black as Cain/May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” Her use of the passive voice in noting that blacks may “be refin’d” displays her belief in a staple of Calvinist theology, namely that human beings do not choose salvation but are chosen by God, the passive recipients of his grace. Her argument for black spiritual equality was also a political statement. If blacks and whites were spiritually equal, then there was no reason they should not have the same political equality and be able to enjoy temporal freedom. Wheatley was joined in this view by a number of black abolitionists in Massachusetts, including ministers and laypeople alike.

Along with the above factors, the Old Testament, which has a number of strictures regulating the treatment of slaves, heavily influenced the legal code of Massachusetts The result of this situation was that slaves in New England (and in Dutch Calvinist-controlled New Netherland) were treated as both persons and property before the law. They were property in that they could be bought and sold, but persons in that they had certain legal protections, including the ability to petition and sue in court. These latter protections remained in place throughout the eighteenth century and were vital to the antislavery movement in the colony beginning in the 1760s. It was the right to petition that helped black abolitionists build an interracial movement of activists during the 1770s and lawsuits that eventually led to the end of slavery in the state after the Revolution.

What impact did Calvinism have on the intellectual grounding of the abolition movement as it moved south in the nineteenth century?

As northern states abolished slavery and slave trading and the focus of northern abolitionists turned to southern slavery, the impact of Calvinism on the movement waned considerably. This was largely a result of the broader transition away from Calvinism that swept the nation at the turn of the nineteenth century. This period saw the massive rise of evangelical denominations such as Methodists and Baptists that called for ordinary Americans to take control of their spiritual lives and choose to be saved.

But for blacks in Massachusetts, there were also local developments that informed their move out of Congregational churches and away from Calvinist theology. Blacks had long been relegated to pews in the balconies of churches, derisively termed “nigger heaven” by contemporaries, where they sometimes could barely see the preacher giving a sermon. When they were slaves there was not much they could do. As they gained their freedom during the 1770s and 1780s, however, the situation became increasingly insulting, and many blacks began to leave their traditional church homes in favor of independent services held in places such as Faneuil Hall in Boston. In addition, the same law that outlawed Massachusetts citizens from slave trading in 1788 banned black immigration from other states, making it clear that blacks were considered second-class citizens at best. I believe this law was another major factor pushing blacks out of white churches and hastening the move away from Calvinism.

If Calvinism did not continue to inform nineteenth-century abolitionism, what were the intellectual legacies of the 1770s on the 1830s?

While Calvinist theology played a smaller role in American abolitionism during the 1800s, the methods and strategies that black activists developed during the 1770s remained key aspects of the movement. The black jeremiad pioneered by Sarter and Wheatley became an even more powerful tool in the hands of thinkers such as Maria Stewart, David Walker, and Frederick Douglass. Even divorced from its Calvinist context, the jeremiad remained an effective way for abolitionists to rally support among their allies and to ridicule the positions of proslavery thinkers.

The politics of respectability was another strategy that Wheatley and Prince Hall used to great effect in their day and would continue to have a lasting endurance not only on the nineteenth-century antislavery movement, but on black politics to the present. Hall especially argued that positive examples of individual blacks and of black communities were essential to gaining white allies for the antislavery movement. Additionally, showing what blacks could achieve—mentally, economically, and spiritually—when they were not enslaved was supposed to be a powerful argument against the institution itself. This idea would be challenged at times by emigrationists such as Prince Saunders who came to believe that no amount of good behavior would alleviate American racism. But by and large, respectability would dominate black political thought from the late eighteenth century to the early 1900s and is a major legacy of revolutionary-era black abolitionism.

In To Plead Their Own Cause, you use a broad range of sources, including religious sermons, political tracts, poetry, and court cases—many of which have not traditionally been used as sources by intellectual historians. To what extent are you making a claim for these types of evidence as part of the field of intellectual history?

One of the major challenges in studying colonial and revolutionary African American history is the paucity of sources, which is exacerbated even further when trying to study early black intellectual history. Black people themselves produced little writing before the nineteenth century and much of what we know about black history in this period is mediated through the work of whites. So in using sources such as Phillis Wheatley’s poems, court cases, or petitions by blacks to the Massachusetts General Court, I was in one sense simply working with what was available. But I was also making an implicit claim that these sources are an essential part of both the black intellectual tradition and American intellectual history more broadly. Caesar Sarter’s 1774 essay on slavery, for instance, may not have been as lengthy or as well-known as John Adams’s Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, yet his argument for intellectual and physical freedom was just as important. Black abolitionists’ writings from this period constitute some of the most forceful arguments in favor of republicanism, the contract theory of government, equal opportunity, abolitionism, and other key subjects of the day.

Conducting research for this project showed me that the lines we draw between cultural and intellectual history are often artificial ones. There’s no reason why a poem or the constitution of a mutual aid society or a speech before the African Masonic Lodge cannot be considered an essential part of American intellectual history. Put simply, the subjects of intellectual history are those people who express their thoughts in some way, whether it be through letters, art, petitions, or published essays and tracts. This was an important part of this book and remains a key feature of the group blog on African American intellectual history that some colleagues and I launched just two weeks after To Plead Our Own Cause was released.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.3 (Summer, 2016).

Christopher Cameron is an associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. He is currently working on a history of African American secularism from 1800 to 2000.