Henry Clay’s funeral on July 10, 1852, was the largest ceremonial occasion ever witnessed in Lexington, Kentucky, up until that time. When the correspondent from the Frankfort Commonwealth arrived in town at 6 a.m., he “found the streets already thronged with strangers and citizens, while every road leading to the city poured in a continual stream of carriages, horseman [sic] and pedestrians.” “The number of people assembled at Lexington, was greater than ever was seen in her streets before,” he wrote. Estimates from other observers ranged between 30,000 and 100,000 in attendance. Lexington’s businesses closed, and black crepe, banners, and portraits of the dead senator adorned streets and houses all over town.

After an Episcopal service at Clay’s estate, Ashland, a grand and solemn funeral procession of local, state, and national government officials and dignitaries accompanied Clay’s remains to the Lexington Cemetery at the western edge of town. The people of Lexington and out of town visitors followed on foot for hours as church bells tolled. The reporter claimed the procession “was the most imposing demonstration of sorrow we ever saw. The carriages in it passed two abreast, and by far the greater portion of its length was occupied by persons on foot marching … its length must have been from a mile and a quarter to a mile and a half long.”

At the grave, upon watching “all that [was] capable of interment” being placed in Clay’s vault, the correspondent was moved to quote U.S. Senate chaplain C. M. Butler’s eulogy to Clay: “Burying Henry Clay? Bury the records of your country’s history—bury the hearts of the living millions—bury the mountains, the rivers, the lakes, and the spreading lands from sea to sea, with which his name is inseparably associated, and even then you would not bury HENRY CLAY.”

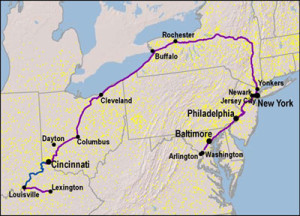

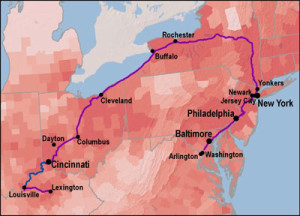

The Lexington funeral commemorating Henry Clay as an esteemed national politician and hometown hero was, however, merely the culminating event in a weeks-long festival of mourning occasioned by Clay’s death in Washington, D.C., on June 29, 1852. Clay’s remains had traversed many of the expansive rivers and lands that he embodied in the imagination of the Senate chaplain and the Kentucky newspaper reporter. For two weeks before arriving in Lexington, Henry Clay’s remains had traveled a long, circuitous path from D.C. through Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Ohio to Kentucky, stopping in major cities along the way so that elaborate funerals rituals could be enacted (fig. 1).

Public grief had played an important role in American political culture since the eighteenth century, but Clay’s funerals marked a turning point toward a more modern form of ritualized mourning that combined an interest in his body with an extensive apparatus of popular culture and publicity. When the sitting president, Zachary Taylor, died just two years earlier than Clay, a huge funeral was held for him in Washington D.C., and the solemn occasion was commemorated with ceremonies and church services around the country. Even so, the commemorations for Taylor were smaller and less numerous than those held for Clay, and Taylor’s body did not play a significant role in the national mourning the way Clay’s would. After being temporarily interred in Washington D.C., Taylor’s remains traveled via rail and steamboat to Louisville, Kentucky, without much publicity and without public celebration. Taylor did receive a second large funeral when he was buried in the family cemetery at Louisville, but the public mourning for Taylor that was quite impressive in 1850 paled by comparison to what took place when Clay died in 1852. Clay’s body, which had not been embalmed, traveled a longer route from Washington to Kentucky accompanied by huge rituals at every stop along the way. (fig. 2)

Clay’s unprecedented funerals owed something to the man who simultaneously embodied and bridged two different traditions of political culture, and something to accelerating anxieties about the cohesiveness of the union. Clay represented a traditional nationalist hero, the kind of man who was supposed to unite the American public in their reverence for him. Turning out to mourn Clay allowed many Americans to express their national identity by taking part in the kind of collective festival that had helped to define U.S. nationalism since the American Revolution; it resembled the rituals that had commemorated George Washington or the martyrs of the Revolutionary War, Joseph Warren or Richard Montgomery—albeit on a scale enhanced by technological advances in printing and transportation. But the supposed unanimity of the American populace had been fractured since 1800 by openly partisan politics, sectionalism, and conflicts over slavery. The historian Elizabeth Varon reminds us that “both the Whig and Democratic parties had emerged from the debates of 1850 and 1851 battered and divided.” Even when both Whig and Democratic newspaper editors around the country agreed about the necessity of mourning Clay as a public hero, they also sometimes allowed party conflict and even presidential campaigning to accompany his funeral coverage. Mourning for Clay became a way to express political anxieties over the longevity of American union even as the trans-sectional Whig party he had helped to found fractured.

Clay was the perfect candidate for this transitional moment because he embodied both union and conflict, and he had been the subject of political pageantry as politics and popular culture developed alongside one another in the early nineteenth century. His long career in national politics spanned almost fifty years: he was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1806 and subsequently served in the House of Representatives, as Speaker of the House, and as Secretary of State. Upon his death, Clay was best known as a four-time-unsuccessful presidential candidate and senator; he served several terms in the Senate from 1831 until his death in 1852. During his long political career, Clay had represented regional interests, but also always managed to express conviction in national unity as sectional tensions changed and grew.

Known as “Harry of the West,” Clay started his career as a western Democratic Republican and built his reputation as a War Hawk advocate of the War of 1812. In the 1820s, Clay, who was also a slaveholder, fused northern, western, and southern interests as the architect of economic development in the American System. Clay helped to hold together disparate northerners and southerners in the Whig party through the 1830s and 40s. He was dubbed “The Great Compromiser” for his role in orchestrating both the Missouri Compromise in 1820 and the Compromise of 1850, and even his political enemies respected his parliamentary acumen. When Sen. Henry S. Foote accused Clay of forsaking southern interests in the Compromise of 1850, Clay responded on the floor of the Senate: “I know no South, no North, no East, no West, to which I owe my allegiance … My allegiance is to this Union and to my own state.” This ability to embody both regional interests and union during his long career enhanced his appeal as a symbol, even after death.

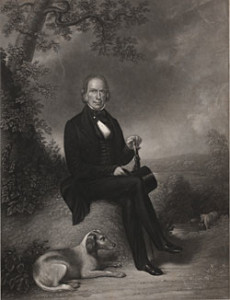

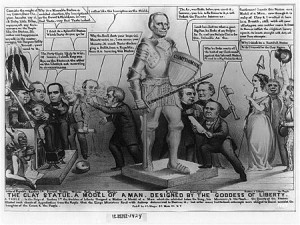

The symbolic appeal of Henry Clay’s remains was also enhanced by the attention contemporaries paid to his physical being. Much of Clay’s political power was grounded in his great abilities as an orator, a skill which many observers related to the special character of his physical body. A frequent presence in political cartoons that became newly popular in the first half of the nineteenth century, Clay’s physical form was as familiar as it was celebrated. As the Whig presidential candidate in 1844, Clay was one of the first politicians whose portrait was sold in elaborate, fine-quality steel engravings meant to be framed and hung on parlor walls. Portrait engravings of Clay were popular, and he was well known as a physical role model (fig. 4 and 5). An 1849 oratorical manual for boys declared Clay the “highest exemplification of masculine charms” and described his “impressive” body and face in exquisite detail. An 1845 phrenology manual that related the talents of great public figures to their cranial measurements declared Clay to be the greatest bodily specimen among politicians because of his large head and good organ placement. S. G. Brown eulogized Clay at Dartmouth College by reminding students that Clay’s oratorical skill depended on “the glance of the eye, the motion of the hand, the firm or yielding position of the body … His form seemed to dilate to a superhuman height, rising, as one said of him on a certain occasion, ‘forty feet high’ in … remonstrance.” The National Era newspaper claimed that “his bodily strength seemed inexhaustible,” especially in the service of a grand cause. Some took this literally; the political cartoon “The Clay Statue. A Model of a Man.” represented Clay as a larger-than-life physical monument to “Compromise,” created by the goddess of liberty to control the chaos of 1850 (fig. 6). A body that in life had been used as a model and turned into a monument could easily become the object of public fascination upon its death. As Clay’s remains toured, several different groups around the country began working on monuments to permanently enshrine him in bodily form.

When Clay died on June 29, 1852 (fig. 3), President Fillmore closed all executive offices, Congress adjourned, and the U.S. Senate immediately took action to prepare an elaborate Washington funeral and to send six senators to accompany Clay’s remains to Lexington, where he had indicated he wished to be buried. Whig and Democratic senators and congressmen rose to eulogize Clay, and the eulogies were reprinted in newspapers in every region of the country for weeks to come. On June 30, the Senate held a solemn funeral for Clay in its chambers. Afterwards, Clay became the first person ever to lie in state in the U.S. Capitol rotunda, as a “vast multitude assembled” to view “all that remains of Henry Clay.” Senate chaplain Clement Moore Butler said, “In many cities banners droop, bells toll, cannons boom, funereal draperies wave. In crowded streets and on sounding wharfs, upon steamboats and upon cars, in fields and in workshops, in homes, in schools, millions of men, women, and children have their thoughts fixed upon this scene” as the nation’s leaders mourned Henry Clay. As a long-time advocate of market activities and internal improvements, Clay would have delighted in Moore’s image of busy Americans pausing in workshops and fields, on steamboats and railroads to commemorate him.

In fact, Moore’s eulogy could have served as a template for the next few weeks, as millions of Americans would, in fact, pause and have the chance to memorialize Clay in person and as millions more followed the progress of his remains in the press. The same rail cars, steamboats, and city streets that Moore imagined actually provided the means for Clay’s body to travel through a large part of the northern United States with greater speed than anyone could have imagined even twenty years before. Transportation improvements had formed a cornerstone of Clay’s nationalist economic program since just after the War of 1812, and although the entirety of his grand federal vision had never been implemented (and had been the subject of serious political battles), the journey of Clay’s corpse over rail, land, and water testified to the eventual success of his vision. As Americans gathered together at many points along the route to catch a glimpse of one of the specially decorated rail cars bearing Clay’s coffin or one of the steamboats or ferries that carried him across lakes and rivers, they saw both the progress of his bodily remains and the progress of his political vision.

Following the Senate funeral on June 30, citizens from Washington, D.C., and all the surrounding towns gathered in the streets to watch as a gilded hearse transported Clay’s remains to the railroad depot. The elaborately decorated coffin, along with six designated Congressional representatives, Clay family members, and other dignitaries, departed at 4:00 p.m. on a special train to Baltimore. Baltimore officials met Clay’s body early on the morning of July 1, and a procession through the city followed at noon. The Baltimore Weekly Sun declared that all businesses closed, and “The city presented a gloomy and mournful aspect … The bells of all the churches, engine houses and other places were tolled … the sidewalks completely jammed up with men, women and children, all eager to take a last look at the remains of the great American statesman.” Clay lay in repose on a specially constructed catafalque in the rotunda of the Exchange Building until the next day, as thousands of people filed by to see his face, which was exposed through a glass window in his metal coffin.

On July 2, the delegation left Baltimore with Clay’s body on another train, and passed through Wilmington, Delaware, where his coffin was again unloaded and placed in repose at City Hall. The plate covering his face was again removed, as “an immense concourse of citizens, male and female, passed through the lines and took a last look at the features of the deceased.” The Congressional committee, now augmented by town committees from both Baltimore and Wilmington, then accompanied the body back on the train to Philadelphia, where they arrived at 9:00 p.m. Clay’s remains were paraded for two hours through Philadelphia in a torch-lit procession to Independence Hall, which “was brilliantly lit up with bonfires, and [where] thousands of ladies had congregated inside its walls to witness the passage of the procession.” Clay’s coffin was placed on a cenotaph in the center of Independence Hall, and crowds of people flocked to see it through the night.

The next morning, July 3, Clay’s remains departed Philadelphia on the steamer Trenton on the Delaware and Raritan Canal to Trenton, New Jersey, where the coffin was placed on another train. As the train traveled through New Jersey, it stopped at the towns of Princeton, New Brunswick, Elizabethtown, and Rahway, where town committees had erected triumphal arches over the tracks and where crowds gathered to see the train, even though they were not allowed to glimpse the coffin, which was stowed safely in a special freight car. The coffin was removed from the train at Jersey City and marched slowly through the streets. At the Jersey City ferry landing, where the delegation departed for New York, “a large concourse of people assembled” under a sign expressing “our love for the remains.”

When Clay’s boat arrived at Castle Garden in New York City on the afternoon of July 3, thousands of people were on hand to greet it, and “an immense military and civic procession was then formed, which escorted the remains to the City Hall” in an open hearse. New York City, long a hotbed of support for Clay and home of the Whig Clay Festival Association, which had organized public birthday celebrations for Clay, tried to outdo all the previous cities in the lavish honors it paid to Clay. The procession accompanying Clay’s remains through New York streets lasted more than three hours as hotels, theaters, “The City Hall, Broadway, Chatham Street, and Park Row were literally shrouded in mourning.” New Yorkers paid respects to Clay as he lay in state at City Hall overnight, although visitors were unable to gaze upon his face. The face plate was not removed from his coffin because of the hot weather that threatened to damage his remains before they reached Kentucky. All day on July 4, “great numbers of citizens” continued to file past his coffin, which was displayed with huge floral tributes and a sign reading “A Nation Mourns Its Loss.” Since Independence Day fell on a Sunday, clergy all over town preached sermons that wove together a commemoration of the national holiday and a eulogy for Clay.

Clay’s funeral delegation departed New York City on the morning of July 5 to travel up the Hudson River aboard the steamer Santa Claus. During the journey to Albany, residents of Poughkeepsie used small boats to deposit floral arrangements on the deck of the Santa Claus. The steamer paused at Newburgh, so local officials could board to pay their respects. At Albany, Clay’s coffin was accompanied by fire companies bearing torches to the New York state capitol, where guards attended the body overnight. The next morning, Clay was placed aboard a special car on the New York Central Railroad. He traveled west through Schenectady, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, and Rochester to Buffalo, where he was loaded directly on the Erie steamer Buckeye State, which carried him overnight to Ohio.

On the morning of July 7, Clay’s remains arrived in Cleveland and then moved via rail through Columbus to Cincinnati, arriving on July 8. In Cincinnati, “a large procession of military, Free Masons, Odd Fellows, Firemen and citizens, conducted the remains through a portion of the city” for more than an hour as over 10,000 people gathered outside heavily draped public buildings. After the procession through Cincinnati, Clay’s remains were placed aboard the U.S. mail boat Ben Franklin bound for Louisville. The steamer Ben Franklin was specially (and expensively) outfitted with a decorated dais and pillars, so that Clay’s coffin could be displayed in the open as it steamed down the Ohio River. The Cincinnati Daily Gazette reported that the coffin “was thus the most prominent object seen from shore, presenting, as it moved down the Ohio, the grandest and most solemn pageant ever borne on its bosom.” Onlookers gathered on the river’s banks to catch a glimpse of Clay’s coffin, and several papers emphasized the touching scene as the boat passed Rising Sun, Indiana, where “grouped together were some 200 ladies, one of whom was dressed in the deepest mourning, attended by the rest dressed in white with armlets of black ribbon.” On July 9, Clay’s body made its final journey via rail from Louisville through Frankfort to Lexington.

The New York Times had opined upon first reporting Clay’s demise that “his death will be celebrated throughout the length and breadth of the land, with heartfelt grief,” and the two-week tour of Clay’s remains seemed to bear out the prediction. The Charleston Courier noted that “such evidences of national sorrow have not been witnessed since the death of WASHINGTON.” Clay’s fellow senator from Kentucky, Joseph R. Underwood, the chair of the committee that accompanied Clay’s remains on the long journey, alluded to the similarity between Clay’s journey and another kind of spectacle familiar to Americans—triumphal tours of politicians and heroes. Underwood remarked upon arrival in Lexington: “Our journey since we left Washington has been a continued procession. Every where the people have pressed forward to manifest their feelings towards the illustrious dead. Delegations from cities, towns, and village have waited on us … It has been no triumphal procession in honor of a living man, stimulated by hopes of a reward. It has been the voluntary tribute of a free and grateful people to the glorious dead.” The cost of Clay’s tour was shared by Congress, municipalities, political organizations, and private citizens. Like the nation-wide tour of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1824 and 1825, for example, celebrating Clay’s remains was meant to remind U.S. citizens of their unity. Clay’s tour also contained elements of campaign tours and the tours of successful candidates such as those conducted by James Monroe and Andrew Jackson. But this time, the politician on tour was a corpse, and the spectacle of mourning replaced the campaign swing.

Just as in those previous tours and in keeping with traditions of American festive culture, press coverage played a huge role in the celebrations that accompanied Clay’s remains on the journey to Lexington. Newspapers in every region updated readers daily on the progress of Clay’s body and detailed the military processions, décor, flags flown at half mast, tolling bells, and the number and character of the crowds of people attending. Even after Clay was buried in Kentucky, church and civic ceremonies in his honor (sometimes accompanied by mock funeral processions) continued in St. Louis; Newark; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; Springfield, Illinois; Athens, Tennessee; Hagerstown, Maryland; Warrenton, Virginia; Milton, Florida; Easton, Pennsylvania; Savannah; New Orleans; Chicago, and San Francisco. The U.S. Senate paid for Clay’s obituaries and eulogies to be published in book form. The press coverage, eulogies, and continuing funeral celebrations effectively spread the mourning experienced by those who directly saw Clay’s remains to a much wider population. S. Lisle Smith, Clay’s Chicago eulogist, noted how widespread the mourning was: “Already has the solemn procession wended its way through our crowded cities, our busy towns, our smiling villages,—amid tolling bells, and booming cannon…Already have thousands, and tens of thousands of freemen gazed upon the lineaments of the great departed.” Another funeral sermon in Newark that July commented on the lingering effect of the massive mourning rituals that had expressed grief “throughout the length of this extended country.” The extensive press coverage, and the republication of Clay eulogies and portraits which further saturated print culture, helped to connect Americans in an “imagined community” of mourners for Henry Clay.

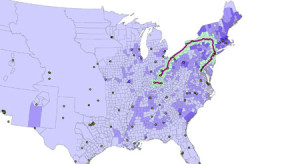

The community of mourners was not entirely imaginary, however. A significant portion of the U.S. population could have seen Clay’s extended funeral procession in person. Consider a map tracing the path of Clay’s remains along rail lines, waterways, and through cities and supplementing it with information from the 1850 U.S. Census (fig. 7). The population of the counties through which the remains traveled was almost 3.5 million, or 15% of the total U.S. population in 1850. If we allow that some people may have traveled to see the body, and add a 20-mile buffer to those counties, the total increases to almost 6 million, or roughly 26% of the population in 1850. Obviously, not every single person in this area viewed Clay’s funeral cortege, but even so, Clay’s trip through some of the most densely populated areas in the U.S. meant that a significant number of people saw the funerals or knew someone who did. When President Taylor died in 1850, close to 100,000 people saw his funeral in Washington, D.C., and tens of thousands more witnessed his burial in Kentucky, but the public did not attend his body in between. A vastly larger number of Americans mourned Clay in person.

Whigs often took the lead in memorializing Clay, but grief for Clay was not their sole property. Comparing the Clay funeral map to maps of the 1844, 1848, and 1852 presidential elections shows that Clay was celebrated in counties that were strongly Whig, but also in several that voted majority Democrat and even majority Free Soil. Several Whig editors did try to juxtapose stories about Clay’s funeral procession with coverage of the 1852 Whig nominating conventions and with positive stories about Whig candidate Winfield Scott. But Democratic editors countered with their own panegyrics and with coverage of Democrat Franklin Pierce’s eulogy for Clay delivered at a nonpartisan meeting in Concord, New Hampshire. Several editors hoped that the public mourning for Clay would “soften” the political struggle leading into the presidential election. But that did not entirely work. The Rochester (NY) Daily Advertiser, a Democratic paper, wrote that “We regret to notice that a few of the Whig papers are attempting to make political capital, or at least to indulge their political spleen at the circumstance that many prominent Democrats and Democratic presses are speaking in laudatory strains of the life and services of HENRY CLAY…We are willing, on such an occasion as this, to drop the curtain of oblivion, and to remember only that in the character of the distinguished patriot, which we can admire and approve.” The same editor later accused Whigs of shedding “crocodile tears” over Clay, when they had not sufficiently supported him since the Compromise of 1850. Mourning for Clay allowed both Whigs and Democrats simultaneously to claim the mantle of impartial national spirit and to engage in partisan battle.

The one group who outright rejected public grief for Clay was abolitionists, further confirming that Clay’s remains functioned as a symbol of the union held together by compromise. Abolitionists rejected any compromise that perpetuated slavery, and therefore they rejected mourning for Clay. The Boston Free Soil newspaper wrote that “no incense can be burnt upon the altar of his memory by a single sincere lover of truth and the right.” A letter to the editor in the Cleveland Plain Dealer raged: “We acknowledge his genius and talents, his eloquence, his statesmanship, but Missouri, black with the curse of slavery sends a groan back to his grave, re-echoed and repeated by his own slaves in bondage … his death has not effaced their wrongs.” The Liberator, the most prominent of all abolitionist papers, reported on a Providence, Rhode Island, abolitionist named Samuel W. Wheeler who hung a sign in his shop window during Clay’s funeral procession reading: “Humanity hath no tears or sorrow to manifest for the death of slaveholders, and other oppressors of the human race.” A Canadian abolitionist newspaper called Clay the “dead … embodiment of pro-slavery.” As far as the abolitionist press was concerned, the national unity created by mourning for Henry Clay came at the cost of “compromising” with slavery and the abuse of black people. This was further confirmed for them when Clay’s will did not emancipate all his slaves. Abolitionists did not want the union preserved if it meant preserving slavery, and so they declined to take part in the spectacle of grief for the Great Compromiser.

Many others who had taken part in the outpouring of public mourning for Henry Clay worried that his passing also marked the death of sectional compromise, as signs gathered that the union itself could be imperiled. The Board of Assistant Aldermen in New York City resolved “that our admiration of his character and our sorrow at his loss, are increased by the reflection that he crowned his splendid labors by devoting … the evening of his life, and the last efforts of his genial spirit and his matchless eloquence, to reconciling sectional animosities, and to vindicating and preserving that glorious Union in whose service he has so long and so faithfully labored.” These New Yorkers and the many others who paid their funeral respects to Henry Clay in 1852 felt like part of an American nation that they hoped could be united in grief for a political hero—as it had been many times before. The spectacle of Henry Clay’s remains traveling thousands of miles across the United States combined the reassuring comfort of familiar political and nationalist ritual and the exciting new opportunity to gaze upon the great man’s body itself.

The tour of Henry Clay’s remains demonstrated well how technological advances in transportation, communication, and printing could include a larger-than-ever number of Americans in the chance to engage in ritualized public grief. Political mourning had been important since the American Revolution, but now lithography, railroads, steam boats, steel engravings, and faster communications spread it farther and faster than ever. But the technological advance did not remove the personal, bodily element of ritualized mourning. In fact, the innovative tour of Clay’s remains offered more Americans than ever the chance to personally encounter the subject of their ritualized grief. It was not just that Henry Clay’s funeral was the subject of newspaper coverage, sermons, and visual depictions. His actual body traveled through densely populated areas as funeral rituals were repeatedly reenacted. The celebration of Clay’s remains combined traditional political culture and well-worn themes of unity in American national identity with a new emphasis on bodily proximity. Clay’s passing body allowed Americans—both those who could see his body and those who subsequently read about the tour or who attended local church services in his honor—to express a sense of national identity in the form of public grief.

The journey of Henry Clay’s remains and the ritualized funeral celebrations that accompanied it marked a turning point in the role of political funerals in American culture and a transition to public mourning on a new scale for political figures in the United States. Widespread mourning for great politicians was not new in 1852, but Clay’s 1,200-mile funeral procession ushered in something new. Political eulogies, sometimes accompanied by mock funerals, comprised an important part of American political culture by the 1850s, but Clay’s funeral marked their coming of age.

Henry Clay’s funeral procession demonstrated an innovation in political funeral ritual—the wide-scale chance for people to interact with the dead politician’s remains. Many observers treated Clay’s body as a sacred political relic. Clay was one of the most powerful and controversial political leaders of the first half of the nineteenth century, but his death set in motion a celebration of him as a nationalist symbol—albeit sometimes a contested one. The journey of Clay’s remains and his ritualized mourning drew together traditions of American political grief and antebellum political campaigning to create a new kind and scale of political funeral—one that would become more familiar to Americans in the 1860s.

Anthropologist Katherine Verdery reminds us that “dead bodies have enjoyed political life the world over and since far back in time,” but Henry Clay’s body played a specific role at a perilous moment in U.S. history. His death allowed Americans to express anxieties over the possible death of their national union in particularly vivid terms. Some Americans looked on the widespread mourning for Clay’s decaying remains as a sign of union—just as the union itself was increasingly threatening to fracture and decay.

But large-scale pageantry and mourning were not enough to guarantee national unity. The political controversy around Clay’s mourning—the squabbling of Whigs and Democrats as the Whig party was weakened by regional tensions; the objections to Clay by abolitionists—made it clear that unity was not absolute and could not be taken for granted. Eulogists were also correct to worry that the loss of Clay’s political talents meant that compromise would become increasingly difficult in the years that followed his 1852 funerals. The travels of Henry Clay’s remains foreshadowed Civil War corpses traveling to be buried and, most of all, the funerals for the assassinated Civil War president, Abraham Lincoln. The innovative spectacle of Henry Clay’s funerals set a precedent, not for future rituals of compromise and union, but for the many ritualized funerals that would result from the Civil War once the union was fractured.

Further reading:

The brief volume by Winston J. Coleman, The Last Days, Death, and Funeral of Henry Clay (Lexington, Ky., 1951) provides basic coverage of Clay’s funerals. The most recent biography of Henry Clay is David S. and Jeanne T. Heidler’s Henry Clay: The Essential American (New York, 2010), though it does not discuss his funeral extensively. To get a flavor of the eulogies delivered for Clay, consult Obituary Addresses Preached on the Occasion of the Death of the Hon. Henry Clay published by the order of Congress in Washington, D.C. (1852); a good analysis of Abraham Lincoln’s eulogy of Clay can be found in Lincoln’s Speeches Reconsidered by John Channing Briggs (Baltimore, 2005). Many newspapers around the country covered Clay’s funeral and the journey of his remains, and many articles can be located in the America’s Historical Newspapers database based upon collections at the American Antiquarian Society.

To learn more about mourning for previous American politicians and heroes, readers should consult Gary Laderman’s book The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1799-1883 (New Haven, Conn., 1996), the volume Mortal Remains: Death in Early America edited by Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein (Philadelphia, 2003), or my own book Sealed with Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia, 2002), which also discusses the phenomenon of triumphal tours. Readers who may be interested in the comparisons between Clay’s funeral and the similarly huge funeral rites for the Duke of Wellington in November 1852 should consult Peter W. Sinnema, The Wake of Wellington: Englishness in 1852 (Athens, Ohio, 2006). One of the most interesting works about how dead bodies can function as political symbols and relics is Katherine Verdery, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies: Reburial and Postsocialist Change (New York, 1999).

To understand more about the political context surrounding Clay’s funerals, look to Elizabeth Varon’s Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2008) and Michael F. Holt’s The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (Oxford, 1999). Readers who want to think more about how Clay’s funerals foreshadowed Civil War mourning should consult Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (New York, 2008) and Merrill D. Peterson’s Lincoln in American Memory (Oxford, 1997).

Census data for 1850 is available from the Inter-University Consortium for Social and Political Research website Historical, Demographic, Economic, and Social Data, 1790-1970, and you can read more about using geographical analysis in history on the website GIS for History. Voting patterns can be observed on the excellent maps in The Historical Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections, 1788-2004, edited by J. Clark Archer, et al. (Washington, D.C., 2006).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.3 (April, 2012).