Rigdon McCoy McIntosh and the Tabor

Unreconstructed Southern Nationalism

Rigdon McCoy McIntosh, born in the trans-Appalachian Southwest, served in two capacities in the service of the Confederate Army. As a soldier, he was among the forces that defended Richmond, Va., and engaged in several key battles in its vicinity. However, he also served as music master and composer of religious music for various occasions while in camp. In contrast to many Southern sacred composers, McIntosh did not write in the more well-known Southern folk-based style of psalmody associated with a form of musical notation called shape-note music. Trained by the Everett brothers, who themselves had studied under Boston reform musician Lowell Mason, he composed psalm and hymn tunes, and extended sacred works that followed the orthodox rules of harmony, a style of music idealized among the genteel classes and polite society.

Unique to sacred music publications in the South, McIntosh’s post-bellum publication Tabor: or the Richmond Collection of Sacred Music (1867) constituted a statement of Southern nationalism, although published belatedly in a Reconstruction-era South in the Confederacy’s most famous former capital city. In this publication, McIntosh invented single-handedly a new artistic medium for the forum for and expression of sacred music. The radicalness of McIntosh’s compilation has been completely overlooked as a result of a number of factors. He embraced theoretically correct harmony, promoted the use of standard musical notation, and was published after the end of the Civil War. Printed in a post-bellum Reconstruction-era South, its author, though born in southern Tennessee, embraced the genteel style of Northern reformers and Southern elites spearheaded by notable Northern musicians such as Lowell Mason, composer of the tune Bethany, commonly known as “Nearer my God to thee.”

McIntosh’s period of professional activity remains between two important periods of Southern sacred music: antebellum evangelical social singing and Southern gospel. Even though he was one of the earliest native-born Southern composers to write Sunday School-style hymnody and Southern gospel music, much of his work appeared too early to be considered directly related to the later gospel music industry. As a result of its notational method and musical style, McIntosh’s Tabor has remained outside the scholarly delineations of Southern-ness. It simply does not fit within current accepted notions of Southern identity. Despite its misunderstood status, McIntosh’s compilation constitutes a remarkable symbiosis of sacred music and secular politics. Through it, he invented a new genre proclaiming formal Southern nationalism, albeit in a post-Civil War environment, in the Confederacy’s former capital.

Rigdon McCoy McIntosh

Rigdon McCoy McIntosh was born in Maury County, Tenn., in 1836. An educated man, he found employment first as a schoolteacher in Triana, Ala., after graduating from Jackson College in Columbia, Tenn. He served in this capacity until the late 1850s when McIntosh met Leonard C. Everett (1818-1867) and his brother Asa Brooks Everett (1828-1875) on one of their teaching circuits throughout Tennessee and the Deep South. The Everetts promoted an elitist style of music that set the brothers apart from other local singing teachers and choir leaders. Falling under their sway, McIntosh quit his job and decided to devote his life to the practice of sacred music.

Rather than teaching, performing, and composing pieces in a traditional style of choral music favored by evangelicals and other enthusiastic denominations where the tenor or high male voice has the melody, the Everetts embraced the modish soprano-led form of four-part choral music identified both with progressive New Englanders, as well as Episcopalian and Catholic musicians in Baltimore and Philadelphia. The tenor-led style was also commonly associated with a form of musical notation called shape-note notation, where the note heads are given different shapes to indicate a note’s place within the solfege. In contrast, the Everetts promoted standard musical notation, disavowing notational shortcuts. Their musical taste reflected their upbringing. Raised in Virginia, the Everett brothers studied in Boston. Commencing their professional careers in the South, they brought to the rural South the most fashionable mode of sacred music then embraced among liturgical churches and a few Methodists and Presbyterians.

Through his exposure to the Everetts, McIntosh championed the soprano-led ensemble, softer singing style, proper enunciation, and a more affected style of performance characteristic of both liturgical-based denominations such as Episcopalians, Catholics, and Lutherans, as well as members of polite society. This style of music was considered scientific by nineteenth-century Americans because it employed a rigorous system of rules learned only through detailed study. Although prized as an ideal by the more genteel classes, this style of music in the twentieth century became a pariah because it appeared to eschew all of the features associated with twentieth-century American ideals. It promoted learning and study over self-reliance. Further, because many of the tunes followed similar melodic and harmonic patterns, all seemed to lack an American spirit of rugged individualism. Though composed in America, these pieces were not considered truly American, but rather vapid imitations of an imported European style.

McIntosh displayed a talent for this progressive style of sacred music and eventually became the Everetts’ colleague and fellow instructor in their various Southern teaching circuits. Although profiting from his association with the Everetts, McIntosh often functioned more as a symbol of Southern legitimacy. As a native-born Southerner, he noticed that at times he represented local authenticity, giving the Everett brothers a certain status that they might not have had otherwise. In contrast, the Everetts were born during the early nationalist period in Virginia, a state that identified as much with the middle Atlantic as its southern and western neighbors before the 1830s. McIntosh was from the trans-Appalachian southwest, and his connections and early professional career encompassed parts of Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama. These teaching circuits proved so successful that he moved to Richmond, Va., to become a partner in the L.C. Everett Company. By 1861, this company had extended networks throughout much of the south and middle Atlantic.

At the outbreak of war, McIntosh enlisted in the Confederate forces, joining the 18th Virginia Infantry, Company H, Appomattox County, on May 7, 1861. For a year, he served as a lieutenant before being discharged for a “personality difficulty” with Lieutenant William Gray of his unit. Soon thereafter, he joined the 25th Battalion Virginia Volunteers, a city guard unit formed after the first attack on Richmond by Union forces, then under General George McClellan (1826-1885). He served in this capacity until the war’s conclusion in 1865. By 1866, he had resumed his former career as a singing instructor and published his first collection, Tabor, or the Richmond Collection of Sacred Music. These compilations of sacred music were commonly known as tunebooks throughout the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Tabor as a Conceit for Southern-ness

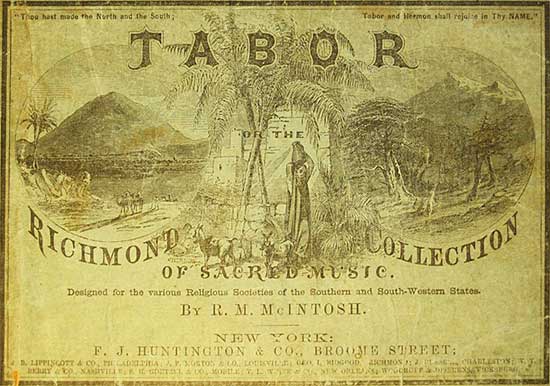

McIntosh’s tunebook contains many direct and implied references to Southern identity, equated with formal Southern nationalism. As a way to demonstrate education and gentility, Southern intellectuals enjoyed creating elaborate conceits, constructed as metaphors for contemporary issues. The front cover of Tabor followed this established tradition and provided the first and perhaps most complex proclamation of Southern identity (fig. 1). Through it he established a metaphoric connection between Richmond, Va., and Mount Tabor, located southwest of the Sea of Galilee in the West Bank. Above the illustrated cover appeared a quotation from Psalm 89, verse 12: “Thou hast made the North and the South; Tabor and Hermon shall rejoice in Thy NAME.” From one perspective, McIntosh followed typical tunebook compilation conventions through his inclusion of the excerpt from the book of Psalms, the one selection of scriptural text universally accepted for musical performance by almost every denomination in the United States.

Although the use of a quotation remained a standard part of many tunebooks, this particular verse drove home the work’s political message. Of the two mountains listed in the passage, Mount Hermon is located to the north and Mount Tabor to the south. Significantly, McIntosh chose to name his collection after the southern mountain. Also, the engravings of the two mountains on the cover seem to relate to Civil War politics. Mount Hermon, located on the right, is depicted with a snow-capped peak, perhaps a reference to Washington, D.C., with its White House. In this sense, McIntosh referenced the two capital cities through the equation of Tabor with the Confederacy and Hermon with the Union. Below the title appears the compilation’s statement of intent: “[d]esigned for the various Religious Societies of the Southern and South-Western States,” again proclaiming its area of reception and intended public. Finally, though printed in New York City, the list of booksellers is limited to Philadelphia and important Southern cities, including Louisville, Richmond, Charleston, Nashville, Mobile, New Orleans, and Vicksburg.

Besides equating the geographic location of Mount Tabor with Richmond, McIntosh’s conceit extended to biblical and Classical history. Beginning in the Old Testament, Mount Tabor became a battleground for the war between the Israelites and Canaanites as described in Judges 4 when the Israelites had become slaves under Jabin, king of Canaan. Deborah, a prophetess and judge for the Israelites “sent and called Barak the son of Abinoam out of Kedeshnaphtali, and said unto him, Hath not the Lord God of Israel commanded, saying, Go and draw toward Mount Tabor, and take with thee ten thousand men of the children of Naphtali and of the children of Zebulun?” Barak responded by having his forces descend from the mountain and attack the Canaanites, destroying the entire army. Paralleling the Confederate perspective of Richmond’s military role during the Civil War, the city repelled an attack by McClellan in 1862, thereby driving off the army of the oppressors who had enslaved God’s chosen people. In this sense, McIntosh equated the plight of Southerners with that of the Israelites.

Displaying not only his knowledge of Old Testament history, McIntosh also demonstrated his mastery of ancient Greek through another reference to Mount Tabor, this time from The Jewish War by Flavius Josephus. Josephus was placed in command of the Jewish rebels entrenched on Mount Tabor during the First Jewish-Roman War in 66 C.E. Vespasian had sent 600 cavalry officers under the command of Platsidus to attack the Jewish forces. Apparently trying the same tactic as Barak, Josephus surprised the Roman army, which initially retreated. However, Platsidus rallied his troops and attacked the rebels, cutting off their line of retreat. The remaining Jewish soldiers surrendered. Again paralleling Confederate history, Richmond suffered a second attack by outside forces, this time under Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant in the nine-month Richmond-Petersburg Campaign (1864-65). As in Josephus, Union forces took Richmond, with Confederates surrendering on April 3, 1865. Like Mount Tabor, Richmond witnessed two major battles, the first a victory, the second a defeat. Displaying the education of its author and a fondness for biblical and classical allusion, Tabor proclaimed its Southern-ness through the mountain’s location and geography, and the political identity of the Israelites through their military campaigns at this location.

Tabor and the American Tunebook

Many of the 561 pieces that constitute the Tabor follow typical conventions of the time period. By the middle of the nineteenth century, a typical tunebook consisted of three main parts. It would begin with a section devoted to the rudiments of musical notation explaining melody, rhythm, time signature, and occasionally vocal production and other practical knowledge for singing. Because these books were intended for use in singing schools, the introductory material often served as a textbook. The second part comprised a selection of congregational metrical psalm tunes organized by poetic meter. This format paralleled the tunebooks by Northern progressives and members of liturgical churches.

Established over the course of the antebellum period, the musical portion of reform tunebooks began with a grouping of tunes in the three standard iambic psalm and hymn meters in the following order: (L.M. [8.8.8.8.], C.M. [8.6.8.6.], S.M. [6.6.8.6.]). Afterwards, the section continued with the particular meters characteristic of Methodist and other evangelical protestant denominations. These meters were originally associated with popular and theatrical song lyrics of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Following this congregational repertory, McIntosh included a final section of more extended pieces of choral music such as anthems whose texts consisted of biblical prose, and set pieces whose texts contained multi-stanzaic settings of poetry. Both of these types of pieces were intended for performance in church as well as for social-devotional occasions. McIntosh concluded Tabor with a selection of liturgical music, almost exclusively Episcopalian service music and Anglican chant for reciting the psalms.

Besides tune organization, many of the original pieces adopted the customs of other contemporary American tunebooks. For instance, new pieces appearing in this collection were almost exclusively by McIntosh, the Everett brothers, and other local Virginia musicians such as J.D. Hunt of Fredericksburg, W.L. Montague of Richmond, and Marcus Justin McGlasson of Farmville. Most compilers of the time operated within a network of regional musicians and professional colleagues. Thus, McIntosh, through the inclusion of his own tunes, and those by his business partners and other locally esteemed singing teachers and church musicians, created both a ready market for his fledgling publication and an informal but effective means for sales and distribution. Further insuring commercial success, this network also extended to a broader geographic area through the availability of Tabor in bookstores in all of the major cities of the Reconstruction-era South.

Likewise, McIntosh’s tune naming followed the practice of the time period. Many of the pieces related to the Bible, being named after biblical place names, such as Horeb and Euphrates by A.B. Everett, and Mizpah by McIntosh. Other tunes were titled for Old Testament figures such as Zurishaddai and Boaz by McIntosh, and Esther and Shemariah by A.B. Everett. Still others referenced McIntosh’s colleagues and associates, including the tunes Brooks and Everett that reference his business parter, and two tunes named McIntosh by W.L. Montague and L.C. Everett. Finally, McIntosh featured tunes with American place names for their titles, including a number of Southern states and cities such as Georgia, Fayetteville, Fredericksburg, and Augusta by McIntosh, Richmond by A.B. Everett, and Beaufort by L.C. Everett.

Alongside these more commonplace conventions, McIntosh imbued his tunebook with a distinctively Southern nationalist sentiment through his naming of tunes after prominent Confederate generals, soldiers, politicians, battlefields, and military encampments. Antebellum Southern compilers did not proclaim Southern nationalism but rather placed their collections within their geographic or regional place within the country. Earlier collections with the word “southern” in their title were compiled only by evangelical musicians who embraced the tenor-led style in shape-note notation. These publications included The Southern Harmony (New Haven, 1835) and The Southern and Western Pocket Harmonist (Philadelphia, 1846) by William Walker of Spartanburg, South Carolina (figs. 2, 3), The Southern Minstrel by Lazarus J. Jones of Jasper County, Miss. (Philadelphia, 1849) (fig. 4), and The Southern Musical Advocate and Singer’s Friend (fig. 5), a periodical with shape-note tune supplements published by Joseph Funk of Singer’s Glen, Va., that began in 1859 and discontinued shortly before the battle of First Manassas in 1861. None of these sources proclaimed any specific Southern-ness other than their works’ titles. In this sense, these tunebooks constituted Southern regionalism, emphasizing their location of origin as a statement of the betterment of music and social singing within a larger American community.

In contrast, the contents of Tabor follow a distinctly Southern nationalist perspective. For instance, A.B. Everett titled one of his hymn tunes Lanier, presumably for the poet Sidney Lanier (1842-1881), who had been active as a soldier in Virginia during the war. McIntosh named his tune Davis after Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederate States of America. Camp Fairfax commemorated where McIntosh was stationed while in the 18th Virginia Infantry in 1861; Manassas was the scene of two major battles in Virginia. A few tunes are named after prominent generals, including Beauregard for Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (1818-1893) (fig. 6), the hero of first Mannassas and defender of Petersburg during the Petersburg-Richmond Campaign, Longstreet after James Longstreet (1821-1904) (fig. 7), Robert E. Lee’s principal subordinate, and Lee by L.C. Everett.

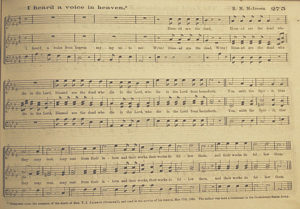

McIntosh also included a few tunes composed while in camp, such as Claiborne (fig. 8), written at “Camp Fairfax, near Fairfax C. H. Va.; Oct. 3, 1861” and the extended choral piece “This is the Day” “[w]ritten in Camp, at Elliott Hill, Va. December 1864.” He also wrote a few tunes for prominent military events. As a symbol of his intimacy with some of the most notable Confederate officers, McIntosh composed the anthem, “I heard a voice in heaven” “upon the occasion of the death of Gen. T. J. Jackson (Stonewall) and used in the service of his funeral, May 17th, 1863” (fig. 9). Clearly, McIntosh remained well connected to many prominent Confederate figures and used these names for the promotion of his tunebook. He also musically enshrined and uplifted Jackson through his genteel use of harmony and compositional style. By composing a piece that employed all of the facets associated with Southern notions of high art, he ennobled Jackson with the politeness of his music.

Tabor and Southern Evangelical Music

McIntosh, though a member of the genteel educated elite of Southern society, attempted to market his concept of Southern-ness to other less polite denominations influenced by popular evangelicalism. As a Methodist, McIntosh included a number of contrafacta, or sacred appropriations of secular songs, a religious song type that descended from the tune collections associated with John Wesley and George Whitefield, and the First Great Awakening of the mid-eighteenth century. The contrafacta in Tabor were a mixture of older popular songs and arrangements of melodies from cultivated, more classically minded composers. As such, contrafacta of “God save the King” and “Rousseau’s Dream,” an early version of the melody known as “Go tell Aunt Rhody,” are contrasted with similar adapted settings of oratorio arias by English baroque composer George Frederick Handel and vocal arrangements of chamber music by Viennese musicians Ludwig Van Beethoven and Ignaz Pleyel.

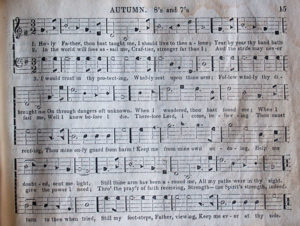

Although most contrafacta were arrangements of tunes by prominent European composers of art music, a number of them were taken from shape-note publications. Though not original to the collection, one popular contrafactum, Autumn, was adapted from an instrumental march of possibly Spanish or Scottish origin. In its instrumental form, this tune appeared in arrangements for a variety of instruments, from solo piano to a full Civil War-era brass band, such as the version by J. Schatzman published in Peters Saxhorn Journal in Cincinnati (1859) (fig. 10, 11).

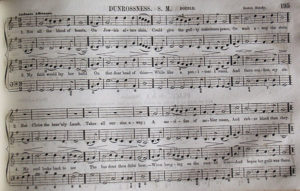

The earliest sacred contrafactum of this tune, Dunrossness, appeared in a northern source, The Haydn Collection of Church Music (Boston, 1850), compiled by Boston musicians Benjamin Franklin Baker (1811-1889) and L.H. Southard. This tune setting displayed all of the progressive features associated with the reformers of ancient-style psalmody (fig. 12). As a demonstration of his scientific attainment, the arranger employed figured bass, or numbers printed below the bass line, to provide a keyboard player with a harmonic outline of the tune for accompanying the singers. Many evangelical and enthusiastic religious groups in the United States at this time did not use keyboard accompaniment, both because of the traditional association of keyboard instruments with Episcopalians and Catholics, and also their high cost. Thus, the specification of keyboard accompaniment testified to the social status of the tunebook and its compilers. Other similar features in the score included its Italian tempo marking, crescendo and decrescendo dynamic markings found in every phrase (between the second and third staves), and a highly decorated or embellished form of the melody. All of these features would have appealed to elitist musicians of the time period.

Autumn, the earliest and only Southern version of this melody, was first printed in The Christian Harp (1865), a collection intended for social and domestic devotion, revivals, and the Sunday school. This tunebook was published by the most prominent shape-note publisher in Virginia: the sons of Mennonite evangelical shape-note singing teacher, musical arranger, and music publisher Joseph Funk (1778-1862), who lived in Singer’s Glen in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Autumn (fig. 13) reflects its more informal intent. It does not specify keyboard accompaniment. The melody is plainer, without any of the embellishments found in the earlier version from Boston, and the texture is reduced to two parts, melody and bass. The harmony is more simplistic, with the bass line limited to three or four notes for much of the piece.

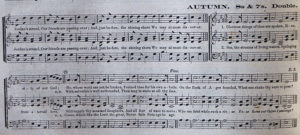

Significantly, McIntosh arranged the Southern version of this tune and not those of earlier Northern reform and evangelical musicians. McIntosh’s arrangement of Autumn (fig. 14), though expanded to four parts, preserved many of the features that characterized Funk’s setting. The melody retains the same simplified melodic shape, and the bass line, though not identical, emphasizes the same clarity as that in Funk. In this sense, McIntosh arranged the tune in the idiom of his formal scientific training, but attempted to bridge the two prevailing styles of Southern sacred music. Perhaps as a symbolic gesture, McIntosh, a resident of Richmond, united the Tidewater and Piedmont areas of Virginia with the western part of the state through his arrangement of Funk’s version of the tune.

McIntosh also included a number of folk hymns, a related tune type to the contrafactum. Among the more enthusiastic and evangelical groups, folk hymns were hymn tunes with no apparent popular secular source for the melody. Sometimes termed spiritual folksongs, these tunes appeared in tune families, with individual variations in the melody paralleling the melody variants of different versions of contrafacta. Folk hymns apparently originated as sacred parallels to their secular cousins. As with the original pieces, many of the folk hymns were given a strongly defined though sometimes mistaken Southern identity regarding the tunes’ origins. McIntosh labeled a few folk hymns as Southern tunes or Southern melodies above the score, despite the fact that at least two of these pieces appeared first in northern evangelical tunebooks.

Of the folk hymns, a few had direct connections to the Shenandoah Valley through the efforts of some of its earliest singing teachers, Amzi Chapin (1768-1835) and his brother Lucius (1760-1842). McIntosh included two tunes associated with the Chapins, Forest better known as Rockbridge, and Memphis better known as Psalm 24th or Primrose. Similarly, he included Golden Hill, a Chapin tune that was arranged later by Ananias Davisson (1780-1857), a Presbyterian singing teacher who resided at Cross Keys outside of Harrisonburg, Va., in the Shenandoah Valley. Davisson published two of the most influential Early Nationalist shape-note tunebooks: The Kentucky Harmony (1816) and The Supplement to the Kentucky Harmony (1820). McIntosh even took the tune Pilgrim (fig. 15) from the first self-proclaimed Southern compiler, William Walker, a Calvinist Baptist and author of The Southern Harmony. Though this tune, more commonly known as Olney, appeared in other earlier tunebooks from the West, McIntosh specifically identified this tune with Walker, The Southern Harmony, and the South (fig. 16). As with the arrangement of Autumn, McIntosh featured the two main styles of Southern sacred music, uniting them under a common identity of Southern nationalism.

Though lying outside scholarly notions of Southern-ness, McIntosh’s Tabor, or the Richmond Collection of Sacred Music reveals his efforts to single-handedly invent a new forum for sacred music. Using psalmody as political ideology, McIntosh legitimized not only the struggle by Confederates to gain independence from the United States, but he also helped to promote the lost Southern cause at the beginning of the Reconstruction era. As an educated veteran living among genteel society, McIntosh demonstrated his taste and modishness through his elaborate metaphoric construct, his professional connections, and his style of composition.

At the same time, he attempted to bridge the two reigning styles of sacred music practiced in the South, thereby presenting a unified South, emblematic of Southern nationalism. Though the ideology behind his efforts remains misguided, injecting a Southern nationalist perspective into sacred music is without parallel in the nineteenth century. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this episode in Southern history revolves around the seemingly contrary defining characteristics of the tunebook itself. Because of its style of notation, orthodox harmony, and the compilers’ pedigree of instruction, The Tabor, or Richmond Collection of Sacred Music defies current notions of Southern-ness. However, finding Southern-ness in Southern music often involves looking beyond the traditional, accepted, and ultimately constructed twentieth- and twenty-first-century notions of Southern identity in American sacred music.

Further Reading:

Several scholarly works have explored the concepts of Southern identity in the antebellum period including: William W. Freehling, Prelude to Civil War: the nullification crisis in South Carolina 1816-1836 (New York, 1965, 1992), Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: the transformation of America, 1815-1848 (New York, 2007), and John McCardell, The Idea of a Southern Nation: Southern nationalists and Southern nationalism, 1830-1860 (New York, 1979). Although the literature on American sacred music of the eighteenth and nineteenth century is somewhat large, a few important works relevant to Rigdon McCoy McIntosh and Southern-ness in antebellum Southern sacred music include: David Brock, “A Foundation for defining Southern Shape-Note Folk Hymnody from 1800 to 1859 as a Learned Compositional Style” (PhD diss., Claremont Graduate School, 1996), Annabel Morris Buchanan, Folk-Hymns of America (New York, 1938), George Pullen Jackson, White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands (Chapel Hill, 1933), Irving Lowens, “John Wyeth’s Repository of Sacred Music, Part Second: a northern precursor of Southern folk hymnody” in Journal of the American Musicological Society 5, 2 (1952): 114-131, David Music, A Selection of Shape-note Folk Hymns from Southern United States Tune Books, 1816-61 (Middleton, Wis., 2005), Lewis E. Oswalt, “A Rare Book for Its Day: the 1874 hymnal and tune book of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South” in Hymnology in the Service of the Church: essays in honor of Harry Eskew, Paul R. Powell, ed. (Saint Louis, 2008).

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Nikos Pappas, an assistant professor of musicology at the University of Alabama, is actively engaged as a scholar and performer of American music from the colonial, early nationalist, and antebellum periods. A recognized Kentucky master traditional musician, he is currently preparing a database of Southern and Western sacred music from 1750 to 1870. His research has received support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, American Council of Learned Societies, the American Musicological Society, the Bibliographic Society of America, the Music Library Association, and the American Antiquarian Society.