What We Talk about When We Talk about Democracy

Reengaging the American democratic tradition

Outside the ranks of political theorists and activists, it’s been a while since Americans have had a substantive, public discussion about democracy. It’s perfectly common to celebrate our country’s democratic political system. Among my students, it’s even more ordinary to take it as a given. There’s still plenty to cheer about in American political practices and institutions, especially if one has been following the elections in Zimbabwe, Russia, or Italy (to name a few places). The problem with the cheering is that it isn’t at all clear what we’re cheering about. Politicians, pundits, and ordinary citizens point with pride to a “democracy” that strangely lacks specifics. Their assumption is that we all agree about what democracy is, so we don’t need to specify.

This vagueness has insidious results. One is a tendency toward definitional drift, in which one kind of democracy serves to justify a completely different kind. This occurs most frequently in American foreign policy, which has long been marked by a slippage between democracy as constitutional government elected by a wide electorate, on the one hand, and democracy as neoliberal reform (a minimal welfare state, privatization of state-owned properties and state-run services, lowering or elimination of barriers to international trade and investment), on the other. The most recent instance of this is in Iraq. The Bush administration’s stated goal of building a democracy in Iraq actually involved a dual agenda: establishing a constitutional, elected government and creating an economy free from a public sector, a strong welfare state, or barriers to international trade and investment. Paul Bremer, the administration’s director of the occupation authority, quickly opened Iraq’s borders to tariff-free imports, privatized state-owned enterprises, opened the country to foreign investment and ownership, and initiated a reconstruction campaign designed to transform the economy into a globalized free market. As they had elsewhere, the two versions of democracy quickly came into conflict. Early in the occupation, towns and cities throughout Iraq held elections, and many Iraqis called for balloting for a new national government. Fearful that elected governments would stymie his economic reforms, Bremer cancelled the local elections, annulled the results of those that had already taken place, and put local, provincial, and national government in the hands of appointed councils.

Another result of our indefinite notions of democracy is that we don’t see what’s at stake in choices about how to conduct politics. Proportional representation, instant run-offs, felon disfranchisement, and voter identification laws get marginalized as wonkish policy debates or partisan squabbles. Most dramatically, few seem to have noticed that the current presidential contest offers voters dramatically different practices of democracy. Since 1968, most congressional and presidential campaigns have treated voters as passive recipients of campaign messages delivered through advertising, the nightly news, and debates. There have been exceptions, most notably grass-roots mobilization through evangelical churches, but standard operating procedure has been to pitch carefully packaged messages through the electronic media. While the McCain campaign (like Clinton’s primary operation) is sticking to this model of campaigning, Barack Obama is combining it with an older strategy, centered on grass-roots organizing and citizen activism. The two campaigns offer dramatically different places for citizens in the conduct of electoral politics, a point that gets lost in reporting on Obama’s charisma, the money chase, and the day-to-day exchanges between the campaigns.

We can best see what’s at stake in our political practices if we refuse to take “democracy” as a given. We ought to be asking ourselves what kind of democracy we want and what kind of democracy a particular leader or movement is offering. Most importantly, we need to accept that to be a democrat (a believer in democracy, not a member of a particular party) is to fight over what democracy is.

That was certainly true during the election of 1828 and its aftermath, long acknowledged as a watershed in the development of American democracy. The past fifteen years of scholarship has shattered an older belief that American electoral democracy began during these years. But it’s safe to say that Andrew Jackson’s presidential bid and presidency intensified, extended, and made permanent democratic practices that had been developing since the 1790s. After Jackson’s victory in 1828, grass-roots organizing and popular electioneering, conducted in an unapologetically partisan fashion by powerful political parties, became the centerpiece of American politics.

The guiding theme of Old Hickory’s 1828 campaign was a promise to end the death grip that an entrenched political elite held on the federal government. Since 1815, the democratic mobilizations of the Jeffersonian era had been eclipsed by fierce factional infighting in which insider methods—building a personal following, intriguing against one’s opponents, spreading rumors—were the main weapons of political warfare. In Washington and in the states, most politicians became insulated from popular pressures—most notably in 1824, when the House of Representatives threw the presidency to John Quincy Adams, even though Andrew Jackson had won a plurality of popular and electoral votes. Capitalizing on this defiance of the electorate, Jackson and his supporters argued that Washington insiders had used intrigue and wire-pulling to rob the people of their sovereignty; rather than being an agent of the people’s will, the federal government had been taken over by a self-perpetuating, unaccountable elite. Jackson proposed a number of reforms (rotation in office, limiting presidents to one term, prohibiting congressmen from taking positions in the executive branch) that aimed at curbing insider power. More importantly, electing the general would restore popular control of the executive branch. A meeting in Sutton, New Hampshire, proclaimed that Jackson was “brought forward by the spontaneous sentiment of the great body of the people,” while Adams “by bargain and management, found his way to the Presidential chair.” At its most fundamental, the “democracy” that Jackson and his followers embraced was a simple one: the right of the voters to choose their elected leaders.

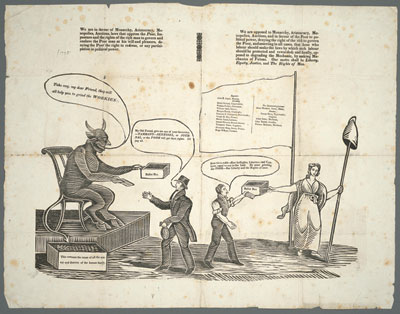

This one right was the bulwark of many others. The Jacksonians revived plebeian Jeffersonians’ view of the world, in which the “aristocracy” was constantly at war with the rights of “the people.” As the Jackson men of Sutton put it, Adams was the candidate of the American aristocracy, which sought to “draw [the people’s] money from their pockets at pleasure; shut up their mouths from speaking against men in power…and give up their right of suffrage.” Jackson’s supporters, on the other hand, were “the bone and muscle of the people” who, along with their candidate, were the stalwart defenders of “democracy and equal rights.” A victory for Jackson would strike a blow for popular rights.

In practice, Jackson’s party at once affirmed and undercut its democratic ideals. The central innovation of the Jacksonians was an organizational revolution. Campaigns between the first Adams administration and the Madison administration had been carried out by two uncoordinated groups: gentry leaders, who sought to line up support for their candidates through networks of personal influence, and self-appointed local activists who drummed up popular support through the press, public speaking, political ritual, and in the most hard-fought states, door-to-door canvassing. Jackson’s campaign was far more centralized. A headquarters in Nashville coordinated the national campaign, sending marching orders to state committees. Those committees, in turn, directed the work of local Jackson Committees and Hickory Clubs.

Thus organized, the Jacksonians took the Jeffersonians’ most intensive electioneering techniques, imbued them with organizational discipline, and began to apply them on a national scale. Though inherited from an earlier generation, the methods the Democrats used were on the cutting edge of mass communications and mass mobilization: print, voluntary associations, mass meetings, participatory ritual. A national network of Jacksonian editors blanketed virtually every congressional district with newspapers, pamphlets, and handbills, trumpeting a partisan message that varied little from place to place. Democrats constituted themselves as a party and invited all voters to become active members. They organized conventions at the school district, town, county, and state level, as well as in nearly every legislative and congressional district, drawing in innumerable men as delegates and providing a powerful impression (often true, to a great extent) that party decisions were controlled by members. Local committees harnessed the energy of still more activists, who visited every voter in their district and got out the vote. Other activists organized meetings, parades, and barbecues. Helped by the popularity of their candidate, these efforts reversed a decline in voter participation that had set in after 1815, bringing hundreds of thousands of new voters, recently enfranchised when most states eliminated property requirements for the suffrage, into politics. Turnout was four times that of 1824 and approached the high voter-participation rates of 1800 through 1815.

Even as it realized the Jacksonians’ vision of elections conforming to the “spontaneous sentiment” of “the people,” the organizational revolution undercut it. After 1824, the very sorts of insider politicians whom the Jacksonians denounced in federal politics embraced Jackson at the state level, turning his candidacy into a vehicle for winning long-term control of their states. By 1828, the middle and top levels of Jackson’s organizations were staffed with such insiders. Like Jackson, most of these men were upwardly mobile men of middling origin. Overwhelmingly, they came from two occupations: lawyers and printers. Most followed politics as an avocation, but all of the printers and most state and national activists sought to make a career out of politics. The managers of Adams’s campaign were largely the same. When they thought it necessary, these men were capable of using the democratic institutions of Jackson’s party to suppress popular initiatives. According to former governor Thomas Ford, early Democratic conventions in Illinois were poorly attended, which allowed “professional politicians” from the county seats to dominate the meetings and control nominations. “If any one desired an office, he never thought of applying to the people for it, but…applied himself to conciliate the managers,…many of whom could only be conciliated at an immense sacrifice of the public interest.”

The power of political specialists became the core grievance in a dissident vision of democracy. Perhaps “dissident” is too strong a word. The Workingmen’s Parties, which flourished briefly in the seaboard cities and inland New England towns between 1828 and the mid 1830s, shared a lot with the Jacksonians. They believed that citizens had the right to choose their representatives without interference, saw unresponsive political insiders as the main obstacle to popular sovereignty, and saw failures in political representation as a source of class exploitation. But they turned the Jacksonian suspicion of “wire pullers” against the Jacksonians, as well as against the other major national party, the National Republicans. The Washington insiders who led the National Republicans were not the only undemocratic leaders, the Workies believed. The upwardly mobile political specialists who dominated both parties at the local and state level were equally dangerous. Politicians, the Philadelphia Mechanics’ Free Press declared, were “among the idle and useless classes…whose affluence proceeds from [workers’] toils and privations.” Through “sly artifices,” a Workie wrote, these “interested, self-appointed individuals” monopolized political office, denying the working classes their right to choose their own candidates and to participate directly in government. Wealthy men themselves, these “OFFICE HOLDERS” adopted banking monopolies, stringent protections to landlords and creditors, and conspiracy laws that allowed the rich to exploit the producing majority.

Workingmen believed that this system of political domination rested on two hallmarks of Jacksonian democracy: partisanship and a populist style of electioneering. One activist wrote that a lawyer-politician, when meeting a worker in a tavern, “will shake hands with you, make the world and all of you, and say such an acquisition to his acquaintance does him honor.” In such a way he will “worm himself into [workers’] good will” and “obtain their votes,” making them “subservient tools for upstarts.” In the same way, partisanship robbed workers of their political autonomy. As the Mechanics’ Free Press put it, “Party…is the madness of the many for the gain of the few.” Particularly dangerous was party discipline—the imperative that party members act in concert. A Workingman declared that “the lawyers, office-seekers, petty magistrates, and speculators seem resolved that we shall shout only when they shout, or sing patriotic airs only when they are pleased to give them out…We must take care not to be ridden by such patriots—it will be attended by evils more to be dreaded than to be priest-ridden.”

For all their disdain for party politicians, the Workingmen adopted their methods wholesale. The New York and Philadelphia parties disseminated their message through party newspapers. They founded Workingmen’s political associations, which greatly resembled the Jacksonians’ Hickory Clubs. Like the Democrats, they made their nominations through conventions whose delegates had been elected at open, district-level meetings, and they appointed committees in every district to promote the election of their candidates. But they sought to purify party usages. Workingmen experimented with a variety of procedural innovations, all of which sought to ensure representatives’ and delegates’ strict adherence to the will of their constituents: issuing binding instructions, selecting nominees by lottery, requiring that nominees be workers, and insisting that nominees be ratified by open meetings of the membership.

Evangelical reformers—temperance advocates, Sabbatarians, opponents to Indian removal and capital punishment, pacifists, abolitionists, woman’s rights advocates—practiced yet another brand of democracy. Before 1840, most reformers eschewed electoral combat. Instead, they sought to transform their culture and society by changing individual belief and behavior. They sought to do so through “moral suasion”—the use of moral and emotional appeals that aimed at a total transformation of an individual’s consciousness. Their model was evangelical conversion. Just as the individual sinner experienced a complete emotional and moral transformation at the moment of conversion, so too were the drunkard, the slaveholder, and the Indian-hater invited to undergo a moral renewal. A Rochester, New York, tavern keeper’s conversion was a typical success story. On the day that he “resolved to renounce the service of the world, and declared himself wholly on the Lord’s side,” he “banished ardent spirits from his bar and house” and offered to forgive the debts of any customer who took the temperance pledge.

Success like this was promoted through methods drawn from the Jacksonians—as well as from evangelical revivals. The evangelical leader Charles Grandison Finney called on his fellow revivalists to emulate those politicians who “get up meetings, circulate handbills and pamphlets, blaze away in the newspapers, send ships about the streets on wheels with flags and sailors” in an effort to “get all the people to…vote in the Lord Jesus Christ as the Governor of the Universe.” Reformers enthusiastically followed Finney’s advice. Let’s take temperance advocates, who built the largest evangelical reform movement, as an example. Converts joined temperance societies, where they publicly committed to self-reform by signing a temperance pledge. They supported one another’s efforts—and pressured backsliders—through vigilance committees. They flooded their communities with newspapers and tracts, recruited ministers, held frequent meetings, and visited the homes of the intemperate. Media campaigns, mutual aid, public gatherings, and pestering were weapons in a battle for “public opinion.” Reformers sought to make the consumption of distilled spirits a matter of public shame.

Though they employed many of the Jacksonians’ methods, evangelicals rejected their definition of the political community. Jacksonian ideology and politics, and to a lesser extent that of their opponents, were founded on a vision of white male citizenship. Although women participated in partisan ritual and supported the party cause with their sewing and cooking, the Jacksonians and their partisan opponents defined electoral organizing, partisan propaganda, and voting as men’s work. African Americans were legally excluded from voting in most states and were kept from partisan ritual and election-day festivities by ostracism and violence. The Workingmen also seem to have limited participation to white men. Evangelicals, by contrast, founded their vision of political community on the equality of souls and the accountability of every individual to God. Everyone, black or white, male or female, was responsible for conforming to God’s will. Thus African Americans were active in the temperance and abolitionist movements, taking leadership positions and publicly speaking, writing, and organizing. Black and white women were the foot soldiers of evangelical reform: they were the majority of those who visited homes, circulated petitions, and raised money for the cause. Although most evangelicals objected, many women took leadership positions and began speaking publicly. Evangelical reform provided the only major avenue for black men and women of any race to participate in politics.

Although temperance advocates avoided open criticism of partisan politics for fear of alienating the partisans among them, such criticism was widespread among evangelicals. Godly men denounced Jackson’s supporters and opponents alike for promoting “depravity” among both political leaders and the electorate. Partisanship encouraged unchristian competition, bearing false witness, and the ruthless pursuit of power. It undermined Christian humility and brotherhood. And it encouraged a stance of “expediency” toward controversial issues, leading Christians to reject Christ’s example in confronting sin. The Reverend George B. Cheever wrote that expediency was “the sacrifice of lasting principles to present emergencies.” As such, it paralyzed “the purity and power of Christianity.”

The most radical evangelical reformers went beyond criticism to call for a Christian transformation of politics and society. In 1837 the abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison embraced what he called “perfectionism,” a kind of Christian anarchism that looked forward to the abolition of all government and “THE REIGN OF UNIVERSAL CONSCIENCE,” in which all human affairs would be conducted according to God’s will, as revealed through unfettered human conscience. Needless to say, party organization and competition for control of the state would have no place in Garrison’s utopia. Angelina Grimke, a follower of Garrison and an advocate of woman’s rights, called for equally fundamental change in political practice. When a critic suggested that women’s engagement in public life would unsex them by bringing them into partisan combat, she responded that “man has no more right to appear as such a combatant than woman, for all the pacific precepts of the gospel were given to him, as well as her. If by party conflict, thou meanest a struggle for power…a thirst for the praise and the honor of man, why, then I would ask, is this the proper sphere of any moral, accountable being, man or woman?” For Grimke, Christ demanded an end to partisan conflict in favor of the politics that evangelicals were already pursuing: a pacific politics of moral suasion.

Jacksonians, Workies, and evangelicals were hardly evenly matched. The Jacksonians hit upon a formula that permitted them to dominate national politics and forced their opponents to adopt their methods. By 1840, when the Whigs finally won the presidency and a majority in Congress, there was very little difference between the two parties’ practice of democracy. The Workingmen were no match for party politicians, who packed their meetings, sabotaged or controlled their nominations, and in New York and Massachusetts, took over their organizations. After winning a third of the working-class vote in 1829, the New York party disappeared after 1830. The Philadelphia Workies won significant support in 1829 and 1830 but lost their supporters to the Democrats thereafter. The party collapsed in 1831. Most Workingmen’s advocates and voters were absorbed into the Democratic Party, where they helped create a radical wing devoted to hard money and democratic suspicion of their own party’s operatives.

The evangelicals were a different story. Though a small minority, they were generously funded by wealthy Christians and could put up a stronger fight against powerful opponents. More importantly, since they did not try to win elections, Democrats, National Republicans, and Whigs had little reason to try to disrupt their proceedings or take over their organizations. (The exception was explicitly abolitionist political meetings, which often were targeted for disruption by northern Democrats eager to maintain the support of their party’s refractory southern wing.) Well into the 1850s and beyond, evangelicals remained a parallel political presence in the North, winning widespread public attention and deeply influencing electoral politics. Starting in the late 1830s, evangelicals began winning allies in the Whig party, while moderate abolitionists, alienated by Garrison’s embrace of perfectionism and woman’s rights, formed the Liberty party. Evangelicals’ politics of mass organization and mass publicity provided an autonomous base from which they influenced party voters and party politicians, both positively and negatively, on policy issues—without seriously challenging the rules of the political game.

Our own political practices and institutions are a direct (though now distant) descendant of the Jacksonians, Workies, and evangelicals. We can see in most political campaigns the Jacksonians’ organizational savvy, their sophisticated use of mass communication, and their reliance on political professionals. On the other hand, contemporary campaigns show only an attenuated version of the Jacksonians’ intense partisanship and very little of their grass-roots campaigning. The Obama campaign represents a revival of the Jacksonians’ emphasis on local organizing. Ironically, it borrowed those methods not from a political party but from the descendants of the evangelicals and Workies—movements like the Developing Communities Project, in which Obama learned to organize. Such cross-fertilization is testament to the capacity of dissident politics, and the competing ideals of democracy it promotes, to renew mainstream politics.

The fights between Jacksonians, Workies, and evangelicals (as well as similar conflicts in other eras) suggest that American democracy was rarely a matter of agreement or an unchanging monolith. The American democratic tradition, I would suggest, has been less a consensus than a fight over what democracy should be. In this election year, it behooves us to participate in that tradition. Alongside our discussion of policy and the personal qualities of the candidates, we ought to think—and fight—about what kind of democracy we want.

Further Reading:

The best synthesis and interpretation of Jacksonian democracy is Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (New York, 2005). Work on dissident visions of democracy is in its infancy, but see Reeve Huston, Land and Freedom: Rural Society, Popular Protest, and Party Politics in Antebellum New York (New York, 2000); Kimberly K. Smith, The Dominion of Voice: Riot, Reason, and Romance in Antebellum Politics (Lawrence, Kans., 1999); and Mark Voss-Hubbard, Beyond Party: Cultures of Antipartisanship in Northern Politics before the Civil War (Baltimore, 2002), all of which deal with a later period than that discussed in this essay. On the Workingmen’s Parties, see Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York City and the Rise of the American Working Class (New York, 1984) and Walter Hugins, Jacksonian Democracy and the Working Class: A Study of the New York Workingmen’s Movement, 1829-1837 (Stanford, Calif., 1960). The literature on evangelicals is voluminous, but for a general work on the temperance movement, see Ian R. Tyrell, Sobering Up: From Temperance to Prohibition in Antebellum America, 1800-1860 (Westport, Conn., 1979). Three books with important insights into the political practices of the abolitionists are Richard S. Newman, The Transformation of American Abolitionism: Fighting Slavery in the Early Republic (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2002); Julie Roy Jeffrey, The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1998); and Aileen S. Kraditor, Means and Ends in American Abolitionism: Garrison and His Critics on Strategy and Tactics, 1834-1850 (Chicago, 1969).

For an account of neoliberal efforts to transform economies across the globe, including American efforts to revolutionize the Iraqi economy, see Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (London, 2007). At the Developing Communities Project, Barack Obama was trained in the organizing methods developed by Saul Alinsky. On these methods and their roots in the labor movement and Christian radicalism, see Sanford D. Horwitt, Let Them Call Me Rebel: Saul Alinsky, His Life and Legacy (New York, 1989).

This article originally appeared in issue 9.1 (October, 2008).

Reeve Huston is associate professor of history at Duke University. He is author of Land and Freedom: Rural Society, Popular Protest, and Party Politics in Antebellum New York (2000) and is working on a book titled Democracies in America: How Politicians, Plebeians, Evangelicals, African Americans, and Indians Remade American Politics in the Early Nineteenth Century.