The Imperial Franklin: Revisiting and Revising North America’s Role in the British Empire

Common-place talks with Carla Mulford about Benjamin Franklin and his views on agriculture, Ireland, and the colonial relationship with Britain.

In the acknowledgments, you note that Benjamin Franklin and the Ends of Empire began as a study of Franklin’s relationship with Native Americans. That is still a core part of your discussion, but can you trace the intellectual journey that took you from that point to a broader project on Franklin’s ideas about liberalism and empire?

The project evolved as I learned more and more about the British Empire and about Franklin. My original concern pertained to constructions of race in the eighteenth century. I wondered whether Franklin was sympathetic to Native peoples, as some have observed, or whether he conceived of Native peoples as obstructing the “progress” of Europeans in North America, whom he perceived to be “better” than all others. The question arose from my study of Franklin’s late writings, especially his “Remarks concerning the Savages of North America” and his comments in the Albany Plan that suggested he admired the Six Nations peoples (the Iroquois) for forming a league and engaging collaboratively in treaty councils. As I delved more fully into Franklin’s writings, a more complicated set of problems emerged: What were Franklin’s views about the British Empire? He didn’t quite seem to be the unquestioning imperialist that many have written about. He seemed again and again to be emphasizing the liberties of all Britons, wherever they lived, to pursue activities that brought them better livelihoods.

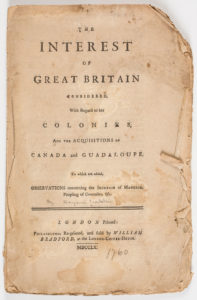

I concluded that while still an imperialist, Franklin also believed that he had come up with a better imperial plan—a more flexible imperial structure, if you will—that would enable Britons in North America to have a reasonable living, secure their borders, and still contribute to the Empire, all without losing all their political rights and privileges as Britons. What evidence do we have that Franklin developed his own potentially workable plan for empire? Franklin’s 1750s Albany Plan of Union, clarified and elaborated on in some long letters to William Shirley, governor of Massachusetts, and several writings from the 1760s, particularly his Canada pamphlet (as it’s frequently called), The Interest of Great Britain Considered, with Regard to Her Colonies, and the Acquisitions of Canada and Guadaloupe (1760).

Conceiving that Britons everywhere had the same liberties, Franklin abhorred the notion that Britons in England considered themselves better than Britons in North America. In addition, he grew increasingly troubled about the conditions of Africans in the European colonies. His affiliations with the Associates of Dr. Bray in London helped him realize that slavery was wrong for both humanitarian and economic reasons. Finally, I discovered that in the 1760s, as he watched the results in Parliament of Britain’s brutal takeover of India, Franklin grew interested in the question of original sovereignty. He began to study England’s presumed sovereignty over Ireland as reports of land and tribal wars in India arrived in London. He studied the Pratt-Yorke opinion rendered on Britain’s takeover of lands in India, in addition to William Bolts’s Considerations on India Affairs: Particularly Respecting the Present State of Bengal and Its Dependencies (1772). Franklin ultimately concluded that if land were taken by purchase and settled and improved, sovereignty over the land belonged to the persons engaged in those activities, not to the monarch who ruled over them at the time they left their original location in order to settle a different location. Sovereignty derived from the Natives’ original title, by use and tradition, and sovereignty transferred to those who acquired Native lands in fair dealing.

As several pieces written in 1773—including two essays, “On Claims to the Soil of America” and “An Edict by the King of Prussia,” and a fascinating letter to William Franklin—indicate, Franklin eventually worked out a legal opinion that the British American colonists, by purchasing Native lands freely offered (not stolen, as he conceived the Penns prone to do in later years), had, by making a purchase and settling the lands, acquired their own sovereign territory from the Natives, who themselves held original sovereignty. His acceptance that Native people held original sovereignty (which disputes the idea of a right of conquest) made a clear case for the British Americans’ sovereignty over the territories they bartered for or bought from Native peoples. I went back to Franklin’s earliest readings and found a thread of liberal ideas, including many of the rights Americans still hold dear, that, I believe, explains the evolution of Franklin’s thinking. It was a complicated process, and it took me two decades to work it out, but I finally found the subject I wanted to write about.

Benjamin Franklin does not lack for biographers or historians. What attracted you to contribute a “literary biography” to scholarship on Franklin?

There are many useful biographies out there on Franklin. I didn’t want to re-tell the same stories about Franklin that others were telling. As a literary scholar interested in rhetoric and propaganda, one who was trained to evaluate the import of a text based on its audiences, I conceived I had something peculiar and interesting to contribute that others might not have observed. Readers have noted that Franklin was a brilliant rhetorician, but few have gone on to try to show the validity of the assessment. I discovered in the long process of studying Franklin’s thought that he was also a brilliant mathematician and economist, as well as a knowledgeable agriculturist. I decided to pay very close attention to what Franklin said but also—and this is important—why he said it, to which audiences, and under what circumstances. In so doing, I was not only writing an intellectual biography, as one reviewer has aptly noted, but also a literary biography that evaluated both the purpose and the rhetorical implications of Franklin’s writings. My purpose went beyond what one might normally do in a biography.

Franklin’s theory of empire, the book argues, rested on an “environmental logic for British colonization.” Can you explain what that means?

I really like this question, because it enables me to speak more fully about Franklin’s study of lands, waterways, and colonial productions.

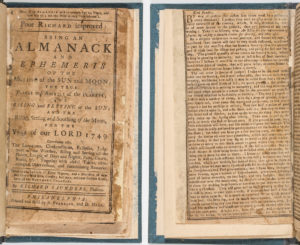

Because he was interested in analyzing Britain’s imperial structure, Franklin was in the habit of studying customs reports. He was very interested in shipping traffic, and he examined bills of lading, where the ships came from, what they were carrying, what they had traded in order to bring in the cargo, and so forth. By nature a very curious person, he could see that certain colonies were more likely to have success harvesting some products and not others, more likely to be able to mine and develop iron or glass or vineyards, more likely to have deciduous trees rather than evergreens, more likely to have an excess of produce to share with other colonies and Britain, and on and on. He asked his friends situated around the Atlantic to send him information on soil quality and productions, and they did so. There are many letters from different people, for instance, who tell Franklin about the trees and soil in their vicinity, the navigability of their rivers, and the likelihood of building canals for transport. He would frequently offer advice on agricultural matters in the Poor Richard almanacs. In Poor Richard Improved, for 1749, for instance, Franklin offers a long opening essay—based on information originally provided to him by John Bartram—on timber and soil. It is amazingly detailed. Adapting Bartram’s information for his own purpose, Franklin suggests that this learned discussion about timber was his friend’s:

“By a diligent observation in our province, and several adjacent, I apprehend that timber will soon be very much destroyed, occasioned in part by the necessity that our farmers have to clear the greatest part of their land for tillage and pasture, and partly for fuel and fencing. The greatest quantity of our timber for fencing is oak, which is long in growing to maturity, and at best is but of short duration; therefore I believe it would be to our advantage to endeavour to raise some other kind of timber, that will grow faster, or come sooner to maturity, and continue longer before it decays.”

He then devotes in the Poor Richard column considerably more space to what kinds of timber can be produced in what kinds of soil, and he speaks to the productivity of certain soils for growing trees. Franklin regularly made observations on environmental matters and husbandry.

These commentaries are often overlooked by historians who are interested in his politics, his social life, or his scientific endeavors exclusive of agricultural matters. As one interested in his views of empire, I found his keen interest in agriculture and cultivation very pertinent to my study of his imperial theories. Franklin had a deep curiosity and knowledge about agriculture. And he was interested in harnessing agriculture to industry and finding economic support for the empire in the different agricultural products harvested in the different locales held as British territories. He writes about these things in general ways in his economic tracts. By looking at the economic tracts alongside Franklin’s particular advice about soil, timber, and agricultural production, I realized that Franklin’s theory of empire was driven by detailed information about the productions of the colonies. Some of this knowledge he witnessed first-hand, some he gained from letters written to him by his wide acquaintance, and some he learned by studying customs reports of imports and exports.

He ultimately determined that if the British administration would just permit the colonies situated around the Atlantic to produce what they wished to and engage in a collaborative (and untaxed) trading system, the Empire could grow, its people would be better off, live longer, and be happier and more willing to participate in governance and defense. This is why I concluded that Franklin’s was an environmental logic for colonial development.

How did Franklin’s reading on empire and political economy influence his arguments for colonial self-government in Pennsylvania specifically and North America more generally?

Well, I guess this is the main argument that the book establishes, so I’ll try to keep this brief.

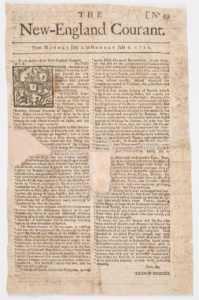

During his youth, Franklin was reading materials about inherited British liberties, such as those discussed in John Trenchard’s and Thomas Gordon’s Cato’s Letters, at the same time that he was reading mercantilist tracts about British colonies and colonial production, such as those written by, for instance, Thomas Mun and William Petty. Indeed, when he wrote his Silence Dogood essay No. 8, Franklin included some rhetorically powerful lines about liberty. This essay was published while he was printing James’s New-England Courant, while James was incarcerated. These early readings were very important to Franklin’s development as an economist and an intellectual. The readings on British liberty suggested to him that people ought to be free to pursue their own livelihoods and their own religious preferences. The readings in mercantilist literature suggested to him that from the imperialist standpoint, people should be constrained to produce certain kinds of goods and not others, and they should not be given too much freedom, because they would not make good choices (with a lot of emphasis on the word good). He didn’t agree with such negative views.

When Franklin got to Philadelphia and saw the political and economic situation there, he witnessed how the colonial system, represented by the Penns’ stranglehold over the Pennsylvania colony, was in conflict with the energy of the people and their resourcefulness as producers. The Penns’ absence from their colony and their desire to exact quit-rents from their presumed tenants resembled the situation in Ireland, where absentee landlords held a majority of the lands, which were worked by day-laborers who could never manage to support themselves because they were working for others. Laborers ought to be able to work out their indenture periods, Franklin reasoned, and then become their own individual landholders, so that they could work for themselves, not some overlord. They would be more inclined to work harder if they worked for themselves, he believed.

Franklin admired the attitude of toleration emulated by many Quakers, but he also saw that their peace testimony compromised the possibility of defense. Many Quakers were willing to support the idea of defense, if it meant defending their own lands and persons, but the idea of using guns and munitions to defend the Penns’ lands or the British Empire as a whole was abhorrent to them. In Franklin’s view, defense of land for the Empire should be paid for (and soldiered by) the Empire, not by individuals whose families and lives were at risk simply because they settled territories that bordered lands held by other Europeans.

The situation in Pennsylvania led Franklin to conceive first that it might be better to have the colony become a royal colony (directed by the king rather than a proprietary family). Eventually, when the plan to make Pennsylvania a royal colony foundered in London, Franklin decided that self-governance (via the elected Assembly) was essential to the security of the colony and the success of its peoples. That experience in Philadelphia enabled him to develop a colonial philosophy that he wanted to see implemented in all British-held dominions. This is the premise of my book.

Scholars of the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Atlantic world have long discussed whether Ireland was a model for English colonization efforts in North America. You argue that the island became a model (or perhaps a cautionary tale) for Franklin as he thought about the role of the North American colonies in the British Empire. Why did the experience of Ireland hold such influence for Franklin?

Franklin first saw Ireland during a visit there in 1771, when he was the particular guest of Wills Hill, Lord Hillsborough, whom he knew to be an enemy to his political endeavors on the colonies’ behalf.

But Franklin had been reading and writing about Ireland—the colonial situation of Ireland—for some time, beginning back in the days when he was establishing himself as a printer and political leader in Pennsylvania. Politically, he was concerned that Ireland seemed to be the kind of colonial model that the Penn family was emulating for Pennsylvania, with absentee landlords and quit-rents expected well above what the economy could bear, keeping the laborers poor while the landholders grew wealthy. Ireland, like North America, had a significant indigenous population that was under social duress.

In the late 1760s, Franklin hoped that he might be able to persuade some of his Irish friends to support independence. When he actually saw the conditions of the laborers in Ireland, however, he realized that that plan was doomed. Hillsborough had spent a day in 1771 trying to impress on Franklin how estate holders’ wealth could be supported easily by harnessing and oppressing the local labor force. Franklin spent the day—he was sick from his sea crossing—trying to be polite, hiding his compassion for the workers and his anxiety about the political situation he was facing.

He had absorbed from his youth a different value system, one based in ideas of personal liberty, the very liberty undermined in Ireland by the Anglo-Irish landlords. That day when Hillsborough showed Franklin around his estate and the countryside in Ireland, Franklin was shocked, and he started to worry about the prospects for British North America. He wrote back to his American friends in letter after letter about the poverty, absence of vitality, and depression of laboring peoples in Ireland. He reported that they were living on potatoes and buttermilk, had no meat in their diets, and were not just unkempt but unclothed (shirtless, and some shoeless). The letters about Ireland and Scotland reveal a level of shock not found in any other of Franklin’s correspondence. He was devastated.

Franklin knew the American colonies needed to be free to operate on their own in a collaborative network of enterprise. His experience in Ireland confirmed that view. He couldn’t get away from there fast enough so that he could write home: “If my Countrymen should ever wish for the Honour of having among them a Gentry enormously wealthy, let them sell their Farms and pay rack’d rents; the Scale of the Landlords will rise as that of the Tenants is depress’d who will soon become poor, tattered, dirty, and abject in Spirit.”

The book’s argument emphasizes that Franklin believed that men were entitled to the fruit of their labors. How did you reconcile that theoretical framework with his participation in slaveholding?

Franklin’s mature views emphasized that people should enjoy the fruits of their labor. For the first part of his life, up until the 1760s, and like many of his generation, Franklin’s concern centered on Britons in North America more than on any other population, whether Germans, Native peoples, or Africans in America (whether enslaved or free). We know that Franklin kept slaves even after he had come to question the validity of slaveholding or its function within an economic system like that he envisioned for the colonies.

As early as 1750, he was concerned that the plantation economy of the South was militating against his ideal of having British North America be composed of independent agriculturalists. (See his Observations on the Increase of Mankind, for example.) But it took another decade for him to be willing to recognize that the intellectual capacities of Africans were like those of Britons and Europeans. His transformation was gradual, pressed on him partly by personal circumstances and friendships and partly by his views of the best economic system for the greatest number of people, a non-plantation system.

His last efforts—the efforts he was engaged in at the end of his life—reveal how deeply Franklin believed Africans to have been wronged, and how essential it was to free them. As president of the newly re-formed Pennsylvania Abolition Society, Franklin wrote a memorial imploring Congress to act to emancipate Africans and African Americans held in slavery. The memorial was taken up in Congress but discussed in a relatively short time. Some wished the memorial tabled and not entered into the congressional record. As might be expected, congressmen from the slaveholding South stood against the idea of emancipation. Franklin would not let it go. His disappointment in his congressional colleagues found an outlet in satire. He went home to write. Franklin’s last essay, a brilliant satire, thoroughly mocked James Jackson, congressman from Georgia, for supporting slavery. He took Jackson’s arguments and using irony and polite urbanity worked step by step to obliterate them. The essay written by Franklin as “Historicus” was published in the Federal Gazette March 25, 1790, less than a month before he died.

Further Reading

Benjamin Franklin to Joshua Babcock, January 13, 1772, in The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 41 vols. to date, ed. Leonard W. Labaree, et al. (New Haven, 1959), 19:6-7.

This article originally appeared in issue 17.1 (Fall, 2016).

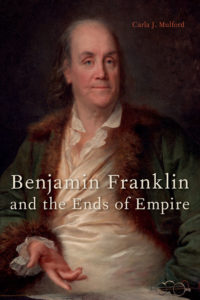

Carla J. Mulford is professor of English at Pennsylvania State University, University Park, and the founding president of the Society of Early Americanists. She has published over 15 essays and book chapters on Franklin and a Cambridge Companion to Benjamin Franklin in addition to her recent monograph, Benjamin Franklin and the Ends of Empire. She is currently writing another monograph on Franklin, this time on the intersections of his scientific and political accomplishments, under the working title Benjamin Franklin’s Electrical Diplomacy.