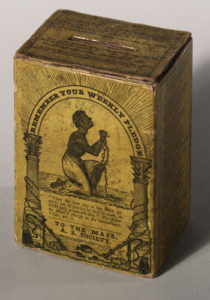

The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s Weekly Contribution Box

This coin box was created by the Board of Managers of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society (MASS) in late 1839 to accompany their fundraising scheme, the “Weekly Contribution Plan.” Modeled on the American Anti-Slavery Society’s (AASS) cent-a-week societies which began in 1838, the MASS’s weekly contribution plan sought to raise money for the cause through the collection of small donations at regular weekly intervals sent to the society monthly. Contributing, according to their ability, one, two, or six cents a week in the box, the grassroots members of the movement could raise vast amounts of money with little seeming labor or sacrifice. At a moment when the general financial pressure of the nation had forced large contributors to withdraw their donations from the cause and when the AASS was on the verge of dissolution, the weekly contribution plan sought to provide the MASS’s treasury the funds to sustain itself. By distributing across all abolitionists the responsibility of keeping the state treasury “constantly supplied” with money to support lecturers and produce print, the plan’s penny capitalism attempted to manage market fluctuations while increasing its members’ personal investment in the cause. A miniature of the treasury to which it is dedicated—”TO THE MASS. A.S. SOCIETY”—the box serves as a sign of the treasury’s larger plenitude and transforms its contributors into stakeholders every time they deposit a coin in its slot. The box compounds its cent. It produces money for the cause as well as interest in it.

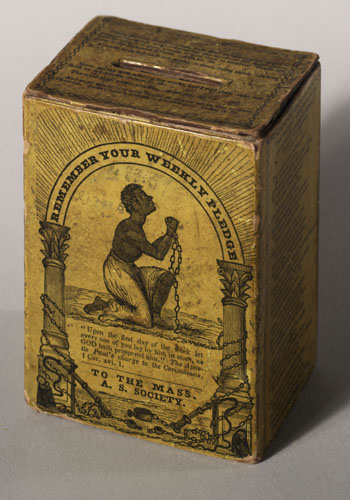

In addition to a treasury, the box also serves as tract. Issued as an “edition” for six and a quarter cents or seventy-five cents for a dozen, the box, according to The Liberator, is “as useful as a tract, as it is convenient as a treasury.” Furnished with “appropriate devices and inscriptions,” the box is covered on every side, as well as the top, with print. The front depicts the kneeling slave framed by rays of light that, in melting the chains of slavery on the Corinthian columns in the foreground, promise her release. Emanating from an arc with the words “Remember Your Weekly Pledge,” the light derives its power from its contributors’ steadfast donations. On one side is a poem titled “A Sabbath Morning Hymn,” by Maria Weston Chapman, which consecrates each contribution as a gift to freedom. On the other are biblical injunctions that remind readers of their duty to deliver the slave from oppression while showing her mercy and compassion. On the top are more quotations from the Bible, which focus on transforming faith into good works. The back lays out the objectives of the weekly contribution plan along with step-by-step directions for how to conduct it. Like most antislavery artifacts, the coin box speaks in several registers: sentimental and religious as well as organizational and instructional. The front image seeks to generate sympathy for the oppressed; the Sabbath hymn and quotations from scripture further increase that sympathy and tie it explicitly to religious duty; and the back explains how good works for the slave are best performed through systematic donations to the antislavery cause. The box’s coordinated message teaches its contributors to turn their sympathy into cents. Through the gathering of cents, abstract feeling is turned into concrete action and sympathy is made to speak.

The alchemy of this artifact—its ability to convert feelings into money—is augmented by its companion tract, The Monthly Offering. Edited by J. A. Collins, General Agent of the MASS, and published monthly (with some irregularity) from July 1840 until October 1842, The Monthly Offering served as the weekly contribution plan’s official organ. Contributors were asked to buy the box as well as subscribe to the tract for thirty-seven and a half cents a year. The synergy between the box and its companion text is evident in the tract’s title, which transforms contributions into a religious offering and reinforces the plan’s monthly collection schedule. The tract is also a visual replica of the box: it not only duplicates the box’s image on its cover but also, in framing that picture with an ornate border, depicts itself as a box. But rather than being full of money, the tract is packed with print that calls to readers to fill their boxes. Designed to “aid and encourage” contributors in their work of “love and mercy,” The Monthly Offering works like the box to “enlist sympathy for the cause, by holding up to view the suffering and benighted slave” and to remind contributors through its regular arrival to be punctual in their payments. Tales within the tract, such as Maria Weston Chapman’s “Pinda,” do both. Pinda, a fugitive slave, not only gains the reader’s admiration for her loyal affection to her husband and industrious self-sufficiency once in freedom, but also models how to convert that sympathy into antislavery action. At the climax of the tale, just before Pinda, finally free, flees with her fugitive husband from Boston, she becomes a subscriber to the weekly contribution plan. Paying in advance, she offers such a large donation that the box must be opened since her Mexican dollar will not fit in its small slot. “[R]ich in the possession of liberty” though poor in funds, Pinda donates her only savings to extend freedom to others with an “effusion of heart, so lovely and so rare.” Like Pinda, contributors too can express their inner feelings and perform their own freedom by giving money to the slave on the coin box. The Monthly Offering supplements the box in several key ways. It reinforces the box’s message that sympathy is most properly expressed through cents. Moreover, its regular monthly arrival prompts the collection of cents and aids their increase by producing more compassion for the slave. Finally, the tract serves as a concrete emblem of what those cents are meant to fund—more print. The box and its tract, then, enact the larger circuit of sentiment, cents, and print that the antislavery movement more broadly propelled: print creating sympathy, sympathy generating cents, and cents producing more print.

Besides serving as a treasury and a tract, a depository for the cause and a stimulator of antislavery sympathy, the box, described as “beautiful,” also functions as a decorative domestic object. Designed to be placed on a chimney mantle or table in the most public room of the house, the box translates antislavery principles into household knowledge and attaches them to middle-class values. Located in (and physically over) the hearth of the home and placed alongside the parlor’s other ornaments, the box reflects and augments the ideals of middle-class domesticity and benevolence that surround it. Visually, the box’s burning rays of truth extend the warming light of the domestic hearth upward, turning the parlor mantle into an altar to freedom. Discursively, the box speaks the middle-class values of sympathy and savings. It espouses piety and charity as well as punctuality and thrift. As a savings bank, the box instills the habit of self-denial even as it emblematizes economic prosperity. The box teaches contributors to perform “generous thrift”—to save in order to give. As a religious shrine, “a little treasury of the Lord,” whose ritual donation occurs every Sabbath morning, the box sanctifies its cents by transforming them into a gift for the slave. Moreover, by displaying the power of benevolence—its ability to turn pennies into freedom—the box makes an accounting of its contributors’ moral virtue and magnifies its meaningfulness. As a parlor decoration, the box reflects its contributors’ refinement and accentuates their social status. Made for display, the box serves as the external sign of its contributors’ interior states—their “right” feelings of sincerity and compassion. The box’s hymn, which tells of “swelling hearts” and “gracious deeds,” along with the sentimental prose and poetry in its accompanying tract, which is advertised as including the movement’s “best writers,” are signs of the contributors’ culture and refined taste. Serving as a conversation piece, the box encourages sociability along with proper social affiliation. As a sign of its contributors’ economic capital, spiritual goodness, and cultural refinement, the box further compounds its cents by constructing a class consciousness for its contributors.

The box, then, provides in miniature a glimpse into the antislavery movement’s larger workings: its systematized fundraising and centralized structure, its production and circulation of innovative cultural artifacts, and its consolidation of middle-class values. By capitalizing on new modes of consumerism and organization and by utilizing an array of discourses and cultural forms, the antislavery movement installed itself at the heart of antebellum culture and middle-class consciousness. Antislavery succeeded not because it stood outside of an emerging mass consumer culture but because, like the coin box, it compounded its growth.

Further Reading:

Information on the weekly contribution plan can be found in The Liberator for the following dates: December 20, 1839; December 27, 1839; January 31, 1840; February 7, 1840, and March 6, 1840. Descriptions of the box are available in The Emancipator, October 1, 1840, and The Monthly Offering (July 1840): 7. The Monthly Offering was collected in two volumes that were published in 1841 and 1842 in Boston by the Anti-Slavery Office.

For more on the organization of the AASS and its role in the middle-class culture industry, see Trish Loughran, The Republic in Print: Print Culture in the Age of U.S. Nation Building, 1770-1870 (New York, 2007); for the place of reform more broadly and abolition in specific in the formation of middle-class identity, see Chris Castiglia, Interior States: Institutional Consciousness and the Inner Life of Democracy in the Antebellum United States (Durham, N.C., 2008).

This article originally appeared in issue 15.1 (Fall, 2014).

Teresa A. Goddu is associate professor of English and American Studies at Vanderbilt University. She is the author of Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation (1997) and is completing a book on the antislavery movement’s role in the rise of mass culture in the antebellum U.S.