A Bell Crack’d

Americans love stories of the Revolutionary era, even if, as recent comments by leading politicians about Paul Revere, the geographic location of Lexington and Concord, and the precise wording of the Constitution suggest, a lack of understanding of the founders often supports that reverence. The Liberty Bell is a case in point. On any given day, a long line of visitors snakes through Philadelphia’s Liberty Bell Center, waiting to see and touch the bell that rang out news of independence on July 4, 1776.

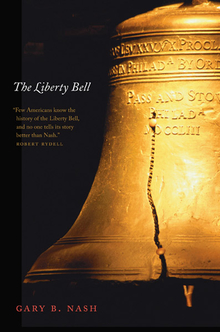

Except that it did not. Yet long before school children sang “The Star Spangled Banner” or recited one of the several versions of the pledge of allegiance, Americans flocked to see the bell. On occasion, the London-manufactured bell traveled about America, but it first hung in Pennsylvania’s colonial State House, and so it was natural that the editors of Yale University Press’s Icons of America series asked historian Gary B. Nash, the author of a number of volumes about Philadelphia, to explain the bell’s cultural significance. In a brisk, fascinating volume sure to irritate those politicians who prefer their history neat and clean, Nash explores the complicated story of symbol that became as cracked and imperfect as the nation it represented.

As the break with Britain approached, the bell pealed even more frequently.

The bell’s story began in the 1750s, several decades before the Revolution. For most of the city’s history, a small bell strung from a branch behind the State House was enough to call the assembly to meeting or warn Philadelphia’s inhabitants of war or fire. But in 1751, legislative speaker Isaac Norris II decided the growing port deserved a bell grand enough to rival “Great Tom” in London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Curiously, Norris opted for a phrase from Leviticus—”Proclaim Liberty Thro’ all the Land to all the Inhabitants Thereof”—to encircle the bell. Trouble with Parliament was not yet on the horizon, and Nash speculates that Norris was aware that just the year before, John Woolman and Anthony Benezet had called upon Quakers to cleanse themselves of the sin of slaveholding. Benezet was openly teaching black children, most of them slaves, to read in his home each evening, and so it was appropriate that in later years, northern abolitionists embraced the bell’s words as symbolic of their crusade to liberate their nation’s inhabitants.

The bell arrived in 1752, but either the stormy passage at sea or inferior packing damaged the bell, which had been tested in London. In its first trial in Philadelphia, the bell cracked. Norris complained to London, but the Whitechapel Foundry—still in business today—insisted the product was sound when it left their office. Philadelphia craftsmen made a mold of the bell before smashing the original into pieces small enough to melt down into a second bell. Although beautiful in appearance, the new bell gave out a dull thud when rung. The third casting was ready by June of 1753, and at long last the largest bell in North America tolled the hours, welcomed the accession of King George III, and marked the end of the Seven Years’ War.

As the break with Britain approached, the bell pealed even more frequently. In rang across the harbor in October 1773 in protest of the Tea Act, and again in 1775 to welcome rider Paul Revere into the city. (Perhaps that is what Governor Sarah Palin meant when mentioning “those warning shots and bells.”) It was silent on July 4, 1776, but four days later it rang to summon residents to hear Colonel John Nixon read the Declaration of Independence. Soon, however, British troops occupied the city. Worried that Redcoats would melt it into musket balls, patriots hid the enormous bell beneath the floor of the Zion German Reformed Church. It saw the sun again when victorious soldiers tried to ring it following news of the Yorktown victory, but by then the State House steeple had rotted to the point that it could not support the one-ton bell.

Despite the fact that the endless recastings left the bell susceptible to cracking, it remained intact until the 1843 celebration of Washington’s birthday (not, contrary to popular belief, the 1835 funeral procession of Justice John Marshall). By then, the bell had already become a national icon, thanks to journalist George Lippard’s assertion that it had announced independence on that first Fourth of July. Moved to the first floor of what was now known as Independence Hall, the bell became a rallying cry for those who hoped the republic would practice what the words on the bell promised. When thirty-five blacks and five whites were put to trial for the so-called Christiana riot, abolitionists gathered outside the hall to protest that “those colored men were only following the example of Washington and the American heroes of ’76” (49). And while on his way to Washington from Springfield, President-elect Abraham Lincoln stopped at Independence Hall to raise the flag and promise a devotion to the principles enshrined there. Just more than four years later, Lincoln’s body lay in state in the hall, the liberty bell pushed to the corner.

In 1885, the bell took to the road. It traveled first to the New Orleans World and Industrial Cotton Exposition in 1885. Along the way, crowds turned out to touch the bell and even sing it serenades. When it passed through Biloxi, the aged Jefferson Davis was called upon to give a speech. Wisely, the former Confederate president chose only to speak of his father’s Revolutionary service, rather than his breakaway country’s attempts to eradicate the bell’s pledge of liberty. Visits to Chicago, Charleston, and Boston followed, and as one of the many photographs in the book suggests, countless children touched and kissed the bell. (In the spirit of full disclosure, I confess I took a photograph of my youngest daughter, Hannah, touching the bell.)

Like any important symbol, the bell continued to be appropriated by various groups. In 1915, the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association printed posters featuring the bell and its words, while evangelist Billy Sunday visited the icon during its travels and promised to use its power “to aid in driving Satan from the Western shore” (125). During the Great War, President Woodrow Wilson used its image to sell war bonds, and to emphasize its connection to earlier conflicts, grizzled Civil War veterans donned tattered uniforms and marched past the bell.

Mostly, however, the bell remained an icon of liberty and resistance. In 1965, civil rights activists staged a protest around the bell, and two years later war protesters staged a “be-in” near the bell while they smoked what Nash drolly describes as “distinctively pungent cigarettes” (169). Appropriately, therefore, when planning for a new home for the bell began in the early 1990s, the National Park Service considered a spot near what had been the rented home of President George Washington, whose household staff included nine slaves brought from Mount Vernon. Having made this courageous decision to reveal the complicated interplay between slavery and freedom in the early years of the republic, local authorities promptly cooled on the idea until Nash and historian Randall Miller launched a public relations campaign designed to force planners to tell the richer story. When Philadelphia’s black community staged a rally on the site in 2002, the Park Service gave way, and the subsequent Liberty Bell Center included not only material on slavery at that cite but featured statues of Hercules and Oney Judge, two of Washington’s slaves who fled his Philadelphia home before he could return them to Virginia at the end of his second term.

On occasion, Nash’s discussion of the bell instead becomes a history of Independence Hall and events that took place outside its doors, but since the saga of the two icons were so intertwined, that is probably unavoidable. Nash’s prose has always been clear and vigorous, but rarely as lively and bright as it is here, perhaps because this story is ultimately happier than those previously told by this prolific scholar.