A Colonial Snapshot: Reading William Hammerton’s “Map of the Southeastern Part of North America, 1721”

Reading William Hammerton’s “Map of the Southeastern Part of North America, 1721”

“What piece excites you?”

It was my first visit to the Yale Center for British Art. The breadth and scope of the collections were so daunting that I resorted to the oldest trick in the book. I asked the curator what she found interesting. Senior Curator Elizabeth Fairman spoke with infectious energy about the materials available, and when she mentioned William Hammerton’s 1721 manuscript map of South Carolina (fig. 1), I could hardly contain my own enthusiasm. My excitement stemmed not merely from the fact that there are so few maps depicting the “Southeastern Part of North America” before the mid-eighteenth century. This map—which details the southern frontier of North America (including the area from Cape Charles in Virginia to Cape Canaveral in Florida, and from the Atlantic coast westward to the Mississippi River)—appears to be the earliest of two known copies of a famous, but lost, map drawn by Colonel John Barnwell. Barnwell, also known as “Tuscarora Jack” for his involvement in the Tuscarora War of 1711, was a redoubtable Indian fighter and frontier settler who traveled extensively throughout the region. (The other period copy of the Barnwell map is housed in the Public Record Office in London).

The Barnwell map became the base for subsequent and well-known maps, such as Mark Catesby’s 1731 “A map of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands” and John Mitchell’s 1755 “A map of the British and French dominions in North America,” which was used during border negotiations after the American Revolution (1782-1783). Though little is known of William Hammerton, who worked as a sailor and was appointed as a naval officer by Sir Francis Nicholson, South Carolina’s governor, in the summer of 1721, his manuscript map offers a virtually unexamined copy of the Barnwell map. Except for a brief mention in William P. Cumming’s The Southeast in Early Maps (1958), the Hammerton map has received little attention.

I had originally ventured into the Center for British Art in the hopes of finding some exciting and eye-catching primary sources for the freshman seminar I was teaching on “War and Rebellion in Early America.” Though Ms. Fairman pulled many items—Benjamin West engravings, maps of Sir Francis Drake’s voyages, and even a military pocket atlas used in the American Revolution—I kept returning to the Hammerton map. My current research project, an examination of the spread and acquisition of information in Southeastern North America, raises questions about how news moved (and who moved it) in the pre-printing press colonial world. Maps are a fascinating source from which to consider both how English colonists negotiated colonial spaces and how those struggles were represented. What role did trade play in connecting South Carolina to the greater Southeast? How were these economic exchanges understood and depicted? What type of information did trade offer the English? How were those far-reaching networks regulated? The Hammerton map offered some answers to these questions.

Seduced by the curator’s passion, I found myself drawn by the striking crispness of the map. Crisscrossing trails connected Charles Town all the way to the Mississippi. The Indian groups along these paths were meticulously identified. The map also included battle sites, well-known trader’s routes, geographic commentary, imperial rivalries, and discussions of possible English ventures into the interior. English Charles Town, Spanish St. Augustine, French Mobile, Indian allies and hostile nations, forts, factories, “pleasant good lands,” as well as swamps were indicated. Every marking on the map made my head swirl. I decided to put my laptop away and stare. Just stare at this magnificent 54-by-31⅛ inch map. I followed each path across the “Southeastern Part of North America.” I read each annotation. I looked at all the small details and then stepped back and stared at the map as a whole. And then I repeated the whole process. It became clear to me that I was not simply reading a map; I was reading history. Hammerton had left us a snapshot of the Southeast in 1721.

The most information-heavy portion of the map extended along the coastline, from Charles Town to St. Augustine. Every inlet was labeled. Every river identified. But the focus of the map was not the Atlantic seaboard. The west was the heart of the Hammerton map. The map pointed to the lands between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, which though far away from English settlements, seemed well within English control. Indian trade and slaving routes connected Charles Town to that vast territory.

With the founding of Charles Town in 1670, the English had expanded relentlessly into the Southeastern interior (fig. 2). South Carolinians re-oriented the Indian trade away from Spanish Florida and English Virginia and, in the process, developed their own extensive and profitable trade connections. The trade routes were the arteries that gave South Carolina a pulse—a pulse that moved with individual traders. The fact that the roads on the map were labeled after the specific traders who journeyed on and through them revealed the extent to which South Carolina depended on key individuals to forge these distant connections (fig. 3).

These lines drew Charles Town closer to backcountry outposts, like Fort Moore and Indian towns in western Florida, and even offered the English access to the Mississippi. But more than simply paths connecting Charles Town to the interior, from point A to point B, these routes were “courses,” “journeys,” and histories of interaction. These trails served as a testament to the region’s long history of trade. They emphasized South Carolina’s persistence as well as the importance of the Indian nations that had facilitated (and those that had blocked) English access. The map showed how these commercial networks afforded the English a wide, albeit uneven, engagement in the region. In 1721, South Carolina was looking to make its presence in the interior more consistent, more powerful, and more felt. The trade routes in the Hammerton map revealed both English desire to expand west as well as the concrete steps South Carolina had taken to make this ambition a reality.

Waiting to foil this English drive into the interior were the French. Stationed all along the map’s western edge were French forts, missions, and outposts. By the 1720s, the French had positioned themselves as South Carolina’s most serious European rival in the region; they had established Fort Toulouse (near the present-day city of Wetumpka, Alabama) in 1717 and made repeated incursions along the Mississippi River. Though the French had a presence in the region dating back to the sixteenth century, these new outposts and trading posts placed them as a permanent and tangible threat.

After studying the map, it was clear to me that the English were expending a significant amount of energy and effort to push west. However, my own research, which focuses on Anglo-Spanish rivalries in the Southeast, forced my gaze away from the French, the west, and the map’s narrative of westward expansion. I looked south to Spanish Florida. How did South Carolinians depict this old neighbor and competitor?

With so much focus on the French and on the west, I was surprised to find that the Spanish figured so prominently in the Hammerton map. Unlike the sparse details denoting the French posts and trading excursions, the section on Spanish Florida was heavily annotated. The Hammerton map offered the location and histories of selected engagements between English South Carolina and Spanish Florida. For example, the map identified several battle sites, including the Battle of Ayubale (labeled Ayavally on the map) and other unnamed towns along the Apalachicola River “where 600 Spaniards and Indians were killed and taken by the Carolinians.” These attacks were part of the violent campaigns led by South Carolina’s former governor, James Moore, in 1704-1706. The English raids had decimated Spanish Indians and missions in Apalachee (western Florida) and removed the Spanish from the area for close to two decades. While the Hammerton map proudly included these English victories, it did not mention Moore’s disastrous invasion of St. Augustine in 1702, which led to the costly and unsuccessful siege of the Spanish presidio (fig. 4).

I realized that the conflicts inscribed on the map had a predictable pattern: total English success and complete Spanish defeat. This presentation transformed the Spanish into an anemic rival, still present in the Southeast but posing no real threat. Whereas Spanish towns and missions were nothing more than a relic of past tensions, French outposts and western territories were the future. Spanish feebleness seemed to tell a history of English strength as well as explain why the English had shifted their attention from the south to the west, from a Spanish to a French rivalry. The Hammerton map made it very clear that the key to the Southeast was in the west. But in 1721, no one knew for certain what direction that key would turn.

How far South Carolina had managed to trade, where and with whom they had established commercial exchanges, and when those relationships truly blossomed all depended on Indians. The amount of detail included on Indians and Indian affairs signaled how deeply South Carolina valued this type of information. Indians appeared in every nook of the map, but their presence was neither arbitrary nor decorative. On the contrary, information concerning Indians was highly specific and strategic. I was struck by how the Hammerton map chose to represent Indian peoples within its vision of English westward expansion. Not all Indian groups received equal treatment in the map; not all Indians groups were of equal concern. But each Indian group was recognized as distinct, autonomous, and yet somehow connected to both South Carolina and to other Indian nations.

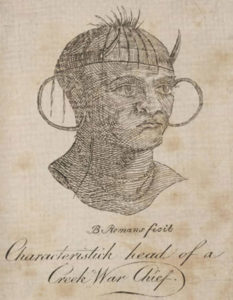

Representations of the Cherokee and Creek provide a telling example. The map described Cherokees as “numerous” and Creeks as “warlike” (fig. 5). The Cherokees and their lands were depicted as having “extensive prospect,” while the Creeks were regarded with trepidation. At the root of this juxtaposition was the Yamasee War (1715-1717), a bloody and violent conflict that had reshaped the Southeast and forced South Carolina to restructure its Indian relations. The English world turned upside down as they waged war against Yamasees and Lower Creeks, Indians who had once been South Carolina’s closest allies. During the Yamasee War, it became a matter of survival for South Carolina to secure an alliance with the Cherokees or, at the very least, to prevent this large Indian nation from joining Yamasee-Creek forces. (The Cherokees ultimately did ally with South Carolina in 1715.)

By the time the map was made, the dust from the Yamasee War had somewhat settled. The Yamasees had been expelled from South Carolina. The Creeks had once again been embraced as friends of the English. And the Cherokees had grown into formidable trading partners. The Hammerton map exposed the war’s open and still bleeding battle wounds, portraying the Creek-English friendship as riddled with mistrust and danger, marred by the experience of the Yamasee War five years before. In contrast, fear and rivalry were nowhere to be found in depictions of Cherokee-English relations. The Cherokees had aided South Carolina during one of the colony’s darkest hours. The map hinted at this budding alliance by labeling Cherokee country as “very hilly,” but “very good land” that would enable both English trade and “English factor[ies].”

As I read the map’s text, I was reminded that the evolving relations among Creeks, Cherokees, English, Spanish, and French were all happening at the same time. The Hammerton map offered a striking visual record of English interactions not just with one group, but with all the diverse inhabitants of the Southeast together. The map showed South Carolina’s strained relations with the Creeks as it depicted its growing friendship with the Cherokee. The map offered no explanation for the ways in which Creek-English interactions affected Cherokee-English relations (and vice-versa), but it did describe Creeks and Cherokees in comparable, albeit different, terms—as if providing two possible alternatives to English-Indian relations. The Hammerton map reminded me of the importance of looking at the larger context when considering specific interactions.

Yet I kept feeling that something was missing. What was it? At first I did not see it. The Hammerton map seemed to draw a fairly inclusive picture of the Southeast region and its inhabitants. It was only as I began to compile a list of the Indian groups mentioned in the map that I noticed a glaring omission: there were no Yamasees and no references to the Yamasee War. How could this be? This massive Indian war had almost wiped the English off the map. At first I thought that South Carolinians merely wanted to erase this event and forget that any Indians had challenged English authority—maps are more often representations of desires than of realities. The map, however, included references to other Indian adversaries. Both Lower Creeks, who had been major players in the Yamasee War, and Tuscaroras, who had embroiled the Carolinas in the massive and costly Tuscarora War, were featured. Why were the Yamasee missing?

It seemed likely that the Yamasee War was nowhere in the map because, truly, it was everywhere. It was the context and subtext informing this map. It had taken me so long to notice that there were no explicit mentions of Yamasees and the Yamasee War because the scars of this failed alliance and conflict were all over the map. Creek Country seemed particularly affected by this unmentionable event. The map listed many Creek towns as abandoned and relocated in 1715 (fig. 6). The map did not explain that the Yamasee War was the cause of this displacement; it merely illustrated Indian mobility and change without offering any reason for these removals. In all fairness, reason probably had little to do with it. The years following the Yamasee War were a time of great anxiety for South Carolinians. The English were shaken not just by the bloody war that had just ended, but by the uncertainty of the future.

In 1721, South Carolina was caught in a difficult balancing act. The English had to weigh the danger and risks brought by the Yamasee War on one hand, and bet on the potential of an aggressive and expansive future on the other. This map showed South Carolina’s gamble. Both a product of the past and a producer of a future, the map was also an expression of a specific moment in South Carolina’s history. The Hammerton map provides a fleeting but vivid insight into the uncertainties and prospects connecting the Southeastern world in 1721.

Further Reading

For more details on maps of the colonial Southeast, see William Patterson Cumming, The Southeast in Early Maps, with an Annotated Check List of Printed and Manuscript Regional and Local Maps of Southeastern North America During the Colonial Period (Princeton, N.J., 1958).

For South Carolina expansion, Indian relations and slaving, and the Yamasee War, see S. Max Edelson, Plantation Enterprise in Colonial South Carolina (Cambridge, Mass., 2006); M. Eugene Sirmans, Colonial South Carolina, a Political History, 1663-1763 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1966); Peter Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 through the Stono Rebellion (New York, 1974); Christina Snyder, Slavery in Indian Country: The Changing Face of Captivity (Cambridge, Mass., 2010); Alan Gallay, The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670-1717 (New Haven, Conn., 2002); William L. Ramsey, The Yamasee War: A Study of Culture, Economy, and Conflict in the Colonial South (Lincoln, Neb., 2008).

For Spanish activities in the region, see Paul E. Hoffman, Florida’s Frontiers (Bloomington, Ind., 2002); Jane Landers, Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida (Gainesville, Fla., 2000); Jerald T. Milanich, Laboring in the Fields of the Lord: Spanish Missions and Southeastern Indians (Washington, 1999); Jane Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida, Blacks in the New World (Urbana, Ill., 1999); John E. Worth, The Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida: Volume 2: Resistance and Destruction (Gainesville, Fla., 1998).

On French incursions in the region, see Daniel H. Usner Jr., Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in a Frontier Exchange Economy: The Lower Mississippi Valley before 1783 (Chapel Hill, N.C., published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg, Va., 1990); Daniel Thomas, Fort Toulouse: The French Outpost at the Alabamas on the Coosa (Tuscaloosa, Ala., 1989).

This article originally appeared in issue 12.4 (July, 2012).

Alejandra Dubcovsky is an assistant professor in history at Yale University. Her current book project is tentatively titled Colonial Communication: Networks of Information in the American South from Cahokia to the Stono Rebellion.