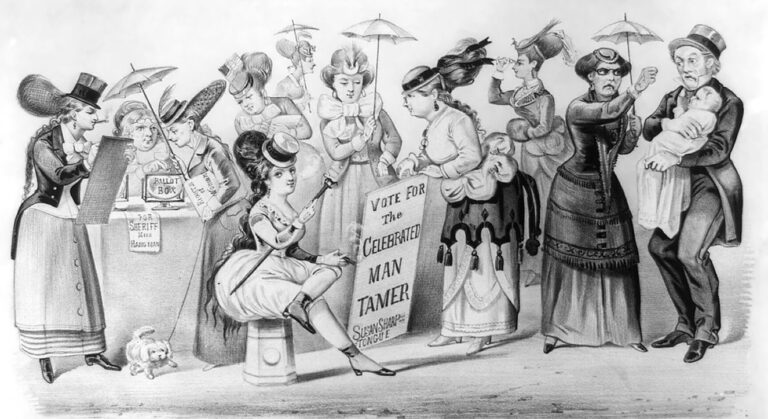

Although the utopia of Annie’s dreams existed on another planet, her eighth dream transported her to a more familiar place: New York City ten years in the future. Within ten years, America elected its first woman president, half of the Senate were women, and prostitutes were no longer arrested and punished for participating in sex work. Instead, their male companions were arrested and placed in reformation houses.

When she returned to this new progressive New York in her last dream, she could not find any women in the city. The factories, workshops, businesses, schools, and hospitals were filled with men, but few women could be found. It was only after Cridge came upon a festival celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the women’s agricultural fair that she realized where America’s women had gone.

Fifty years earlier, the city struggled with a large population of impoverished women with little land, few opportunities, and no support. To remedy their circumstances, a large class of widows, wives, and single women moved out of the city to a vast space of uncultivated land. There, they started their own farms and made agriculture women’s work. Over the years, the grain, fruit, and vegetable farms they cultivated became their source of happiness and health. When Cridge awakened from her final dream, she hopefully asked “may not this dream, after all, be a prophecy?”

In Cridge’s story, America’s women embarked on an agricultural quest to achieve happiness, health, and control over their futures. Even after they achieved political and economic equality, laboring in unsafe and unhealthful factories harmed their physical and spiritual well-being. Cridge’s American utopia did not singularly hinge on technological innovation or economic equality. It was a comprehensive achievement that combined political and economic equality with women’s autonomy and health.

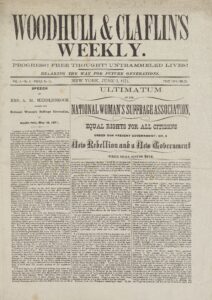

In 1870, Cridge acted upon her agricultural dream and left the East Coast for an agricultural colony in Riverside, California, where she remained until her death in 1873. Like many other vegetarian socialists, Cridge believed women’s emancipation and healthy living for all humans required a large-scale reorganization of societal relations. A sanitary agricultural farm where families and individuals could live cooperatively and grow fruits, vegetables, and grain was a means to achieve a better world. In this regard, Man’s Rights was an individual prophecy for Cridge. Unwilling to wait for the day when the utopia of her dreams finally appeared, she took matters into her own hands and spent the last years of her life attempting to make her work of fiction a reality. In an obituary published by Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, her husband Alfred wrote that “believing that occupation on the land was the keystone of woman’s independence,” his wife spent the last of her lifeforce sustaining the colony.

Read: Annie Denton Cridge, Man’s Rights; or, How Would You Like It? Comprising Dreams (Boston: William Denton, 1870).

Annie was not the only woman who published powerful works of utopian fiction in the mid-to-late 1800s. Decades before Charlotte Perkins Gillman published her popular work of utopian fiction, Herland, in 1915, utopian authors Marie Howland, Jane Sophia Appleton, Elizabeth T. Corbett, and Zebina Forbush published their own visions of a more equal, healthier, and perfect future on earth. Marie Howland, like Cridge, was also a utopian-socialist who participated in the Associationist movement and lived in several communes throughout her life. Cridge and her fellow utopian authors were part of a vibrant community of women authors who used their literary prowess and access to periodicals such as Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, Woodhull & Claflin’s Weekly, and Godey’s Lady’s Book.

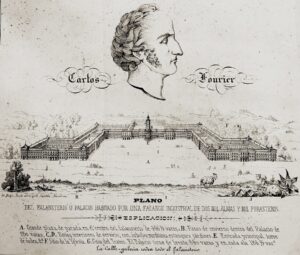

Cridge’s short story, not to mention her illustrious reform career, represents a more radical but influential side of mid-nineteenth-century politics. Existing alongside America’s more traditional reformers who advocated single-issue causes such suffrage and abolition, and the moral and bureaucratic reformers who looked to clean up America’s cities and political system, a cadre of radical socialists worked to reorganize America’s social and economic institutions and remake society into a second Eden. From the 1860s to the 1880s, Americans founded multiple utopian-socialist communities that highlighted the importance of a vegetarian diet and clean living such as Hygieana, Cedar Vale, the Lord’s Farm, Societas Fraternia, Joyful, Israelites, and various Brotherhood of Light and Theosophist communities. Cridge was a pioneer within this group of reformers who, from the 1840s to the 1870s, persisted in their efforts to remake the world, starting with the United States, into a happier and healthier utopia.

Further Reading:

Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

Carl Guarneri, The Utopian Alternative: Fourierism in Nineteenth-Century America (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1991).

Justyna Galant, “Ruptures in Separate Spheres: Deconstruction of Cross-Gender Solidarity in George Noyes Miller’s The Strike of a Sex and Annie Denton Cridge’s Man’s Rights,” Utopian Studies 29 (no. 2, 2018): 176–196.

Alfred Denton Cridge, Utopia; or, The History of an Extinct Planet (Oakland, Cal.: Winchester & Pew, 1970).

This article originally appeared in June 2022.

Ashley Garcia is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. She researches the history of utopian socialism in the United States and her dissertation examines the Associationist movement of the 1800s.