It was clear now that they had made their way to George Washington at Cambridge. Knox had been spotted at the battle of Bunker Hill. Washington had put Knox in charge of artillery and had made him a colonel!

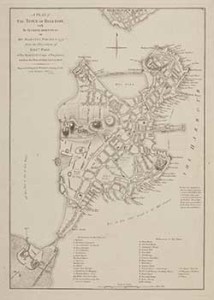

Within hours of the British troops’ departure, five hundred of Washington’s soldiers were clambering over the barriers and working their way around the fortifications at the Neck. The scuttlebutt in Boston brought news that Washington knew about the smallpox there, for he had sent to reconnoiter the town only men who had previously survived smallpox or had been inoculated against it. Not until this detachment finished its reconnaissance did others come in to shore up the defenses the British Army had wrecked in its departure: evidently, Washington was guarding against a sneak counter-attack by General Howe.

As Mather Byles and his diminished family reached home and looked across the Boston Neck from their upper rooms, they could see the rebel guns on Dorchester Heights, but they could also see strewn around the Neck the wreckage of British equipment discarded or broken up in the hurried departure. The town, with its entrenchments and fortifications, was instantly a shell of a civilian town with scores of houses hurriedly left vacant as hundreds of families closed them and fled for safety. For a couple of days, the only soldiers seen on the streets were some Continental work-details. But that changed on the morning of March 20.

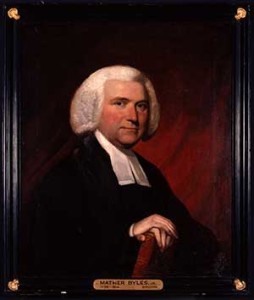

Word traveled quickly: Washington was planning to march his army into Boston. The townspeople, long penned up during the siege, were curious to see this Virginia aristocrat who was a stranger to them. But Henry Knox was a local man. When he and the other Bostonians accompanying Washington marched into town, they would parade down the familiar streets where they had grown up and lived as British subjects all their lives. Their relatives and friends—even a Loyalist friend such as old Mather Byles—were eager to see them again for the first time in nearly a year. Knox would surely have a prominent place in the parade, and Byles decided to find a good vantage point along the street so that he could behold the young bookseller now transformed into a colonel in this audacious, just-formed army of provincial rebels. Like Falstaff awaiting the arrival of the newly crowned Henry V, Byles was waiting for his own (somewhat Falstaffian) Henry to ride by.

He heard them before he saw them. A great huzzah had gone up when the gates at the Neck had been thrown open, and the sound carried as people hurried to their windows or took up posts on the streets to see the parade. Soon Washington and his staff rode smartly into view. He was as tall as reports had said—as tall as Doctor Byles, probably taller—and he sat a powerful horse impressively. He had the look of command. And arrayed behind him rode his staff officers. Surely Knox would be easy to find among them. There he was, as fat as Byles had remembered him, riding a fine horse and handsomely got up with a splendid coat, polished brass and leather. His cheeks were red with the excitement of entering Boston as a hometown hero, and he was smiling and nodding to acquaintances waving to him from their doorways and from the margins of the streets. Byles shouldered his way through a couple of onlookers so that he could catch the eye of Henry Knox as he came toward him. Their eyes met, and Byles, with a smile, sang out this greeting: “I never saw an ox fatter in my life!”

As with all plays on words, this one took a moment to register, a second while the minds of bystanders and Knox himself translated “an ox” to “a Knox.” But just a moment, for there followed a titter, then a few snorts, and then some nervous laughter as the onlookers caught the joke but also its audacity—so typical of the town’s greatest punster, to be sure—but what in the world was the old parson thinking? Obviously, he meant to be jocular—but Colonel Henry Knox was not amused. He jerked his mount’s head away. As he spurred his horse, some observers were sure they saw him mouth the words, “Damned fool.”

As Knox and his artillerymen moved down the street, several people in the crowd mentally added Byles’s latest pun to a list of his offenses that they had quietly been compiling during the past year spent under the thumb of British military rule in the dismal town. This was the same old Byles, habitually dispensing his wisecracks and puns on all subjects, even the political. The doggerel of 1774 still held true in 1776:

With strutting gait, and wig so great,

He walks along the streets,

And throws out wit, or what’s like it,

To every one he meets.

But three days ago, General Howe and his troops had sailed away somewhere, and today a new order was about to replace the British commanders in rebellious Boston. With a prominent but irritating Tory minister living in their midst, Boston patriots saw in Mather Byles a handy opportunity for an illustration of how they would wield their power and who would truly rule at home. Byles swiftly became their target. The pastor of the Hollis Street Church, whose meetinghouse had been appropriated as barracks for the British army and whose apostate clerical son had gone over to the enemy, would learn to bridle his tongue, or it would be bridled for him.

The first “trial” of Mather Byles the Elder

In the early summer, the hopes of the Byles family for reconciliation crashed when independence was declared in Philadelphia in July. The printed Declaration arrived in Boston on July 18, 1776. Thomas Crafts, Sheriff of Suffolk County, read the document in public, receiving three huzzahs, and a great celebration followed. Gun batteries on the surrounding hills fired thirteen rounds, thirteen infantry units fired in succession, and church bells pealed throughout the town.

Citizens ripped down all signs of royalty in Boston, including the king’s arms that were displayed at the State House, throwing them into a bonfire in front of the Bunch of Grapes Tavern. “Thus ends royal authority in this State,” wrote Abigail Adams to her husband, “and all the people shall say Amen.”

A little more than three months earlier, however, just a few days after Byles’s congregation had returned to Hollis Street Church following the evacuation, his former friends, prominently including his Congregational colleagues whom James Otis would come to call the “black regiment,” had organized a plan to punish him for his Loyalist opinions, his sardonic puns, and his friendship with the British during the siege. Now, with political independence declared in July, his church seized its opportunity and brought Byles before the church and congregation to dismiss him. (The “church” refers to members in full communion; the “congregation” included members not in full communion.) This trial was the first of two Byles was to undergo in the coming year.

In late July 1776, the people of his church publicly summoned Byles to the meetinghouse for a hearing before the male members of the congregation. The most prominent Congregationalist minister in Boston, the bellicose Charles Chauncy of the First Church, had spent the siege under self-imposed exile in Brookline. He seems to have instigated the movement to oust Byles from his position. Yet Byles, having served Hollis Street Church since its founding in 1732, was not about to give Chauncy the satisfaction of seeing him sweat under an interrogation or, worse, meekly present a confession of error or an apology.

As an eyewitness later recalled, when the men of Hollis Street assembled in the meetinghouse gallery to bring their grievances against the best preacher in town, he made them wait, fidgeting nervously in their seats. Suddenly, the door opened, and Dr. Byles, wearing gown and bands, a full wig, and a three-cornered hat, appeared in the doorway. Shoulders back and head up, he walked with a stately tread while passing under the gaze of his accusers. Reaching the pulpit, he ascended the stairs, removed his hat, slowly placed it on a peg, rose to his full height, looked out at them, and finally seated himself. Silence. After a few moments, Byles turned to the gallery to face his accusers.

“If ye have aught to communicate,” he said, in the deep voice they had heard on so many Lord’s Days—”say on!”

Motionless silence from the assembly until finally a deacon rose, unfolded a paper, and began to read in a tremulous voice: “The Church of Christ in Hollis Street …”

“Louder!” commanded Dr. Byles.

The deacon tried again, raising his voice: “The Church of Christ in Hollis Street …”

“Louder!” thundered Dr. Byles for a second time.

The deacon tried for a third time, his voice now squeaking in following his pastor’s command: “The Church of Christ in Hollis Street …”

“Louder!” interrupted Dr. Byles for the third time.

Finally, the deacon began to shout the bill of charges against Mather Byles. When he reached the third charge on the list, Byles rose to his feet and proclaimed, “‘Tis false! ‘Tis false! ‘Tis false! And the Church of Christ in Hollis Street knows that ’tis false.” He reached for his hat, placed it on his head, and descended the stairs. In a measured, unhurried manner, he dramatically strode from the meetinghouse, closed its door behind him, and never entered it again.

In declaring its independence of Dr. Byles, the Church of Christ in Hollis Street brought the following charges against him, all of them political and none of which Byles had seen in advance: that he “associated and spent a considerable part of his time with the officers of the British army, having them frequently at his house and lending them his telescope for the purpose of seeing the works erecting out of town for our defense”; that he neglected “to visit his people in their distress, and treat[ed] the public calamity with a great deal of lightness and indifference”; that he prayed “in public that America might submit to Great Britain, or words to the same purpose”; that he used “his influence to prevent people from going out of town, and [said] that the town would be inhabited by a better sort of people than those who had left it, or words to that purpose”; that he had been “officious to lend his aid and assistance to furnish our enemies with evidence against the country, by signing a certain paper at the request of Gen. Gage, relative to what one [Lt. Hawkshaw] said (or did not say) respecting the battle at Lexington”; that he was “unwilling to preach on a fast-day appointed by Congress, when with difficulty he was prevailed to preach one-half the day; and further, his refusing to have two services on the Lord’s day”; he regularly met “on the Lord’s days, before and after service, with a number of our inveterate enemies, at a certain place in King-street, called Tory Hall”; and that he allowed the British to take away “the fences belonging to the society, the seats of the pews, etc.”

Byles did not stay to hear all these charges. It is likely that the third charge read—that he prayed in public that America might submit to Great Britain—triggered his outburst and dramatic exit, for he had always refrained, on principle, from preaching politics in his sermons. When pressed to take a political stand during services, he had replied, “I have thrown up four breastworks, behind which I have entrenched myself, none of which can be forced. In the first place, I do not understand politics; in the second place, you all do, every man and mother’s son of you; in the third place, you have politics all the week—pray let one day out of seven be devoted to religion; and in the fourth place, I am engaged in a work of infinitely greater importance. Give me any subject to preach upon of more consequence than the truths I bring to you, and I will preach upon it the next Sabbath.” The charge that he had prayed in public for America’s submission to Britain would provoke his denial: “Tis false! ‘Tis false! ‘Tis false!”

For the other charges, however, there was plenty of evidence. And although he had not preached on politics before the siege, there was a risk that he might start now. Removing him from the pulpit removed that threat. The bill of particulars demonstrated that during the siege year between April 19, 1775, and March 20, 1776, someone had quietly, but carefully, observed and recorded his activities—and now those notes were codified as a matter of record.

Byles left the Hollis Street meetinghouse on Friday, August 9. On that day, the Provincial Council ordered every Massachusetts congregation to read the Declaration of Independence two days later. On that Sunday, therefore, Charles Chauncy kept his congregants after morning service, read his people the catalogue of accusations against the king, implored, “God bless the United States of America,” and commanded all the people to answer with a solemn Amen. By leaving his church on Friday, however, Byles escaped having to do the same—or trying to invoke his rule against preaching politics from the pulpit. One week after Byles closed the door behind him, on August 16, the Hollis Street church and congregation met and voted to dismiss the Reverend Dr. Byles from his pastoral charge.

Except for Byles, all of Boston’s Congregationalist ministers were in Chauncy’s camp politically, as were most of their colleagues elsewhere in New England, but what happened at Hollis Street troubled clergymen throughout the region. News of this dismissal on political grounds, with no council called and no theological charges brought, spread rapidly. The events at Hollis Street were highly irregular, nearly unprecedented in Massachusetts’s Congregational history. Pressed by several worried Patriot clergy about the precedent Hollis Street had set (and by the contradiction between Chauncy’s lifelong opposition to dismissing a minister without calling an ecclesiastical council), Chauncy merely stated that “Byles is not fit for a preacher” and that “it was an irregular time & we must expect things irregular.”

The State follows the Church: The second trial

Byles’s opponents, however, had only just begun. The church had acted, and now it was time for the state to punish him. Only a week after his dismissal from his pulpit, the political apparatus went to work. The Boston Committee of Correspondence and Safety called a hearing to question “a number of Persons who had heard Dr. Byles express himself very unfriendly to this Country.” Several of his Hollis Street worshippers testified as to the Doctor’s sarcasm—his insulting joke about fat Henry Knox surely came up—but the committee took no punitive action. That action needed a state law that could be applied to Byles, and that law got passed in the spring of 1777.

On May 10, 1777, the General Court of Massachusetts passed an act providing for “procuring evidence, preparing lists of suspected persons, for their apprehension, their trial by jury, their punishment on convictions, with sundry regulations as to the disposition of their property and estates.” Boston swiftly put this new law to work. The town meeting of the following Saturday appointed William Tudor to “procure Evidence that may be had of the inimical Dispositions, towards this, or any of the United States, of any inhabitants of this Town, who shall be charged by the Freeholders of being a Person whose Residence in this State is dangerous to the public peace or Safety.” The scale of crimes had now escalated from actions to attitudes. The meeting recommended to the General Court that anyone with an inimical disposition be “immediately apprehended and confined.” It also called upon the Boston Selectmen to “retire & make a List of such Persons,” which the Selectmen promptly did, publishing it two days later. On the list of twenty-nine men, Mather Byles, D. D., stood second, behind Ebenezer Norwood and ahead of Benjamin Phillips. It was clear who would rule at home and who would be ruled.

Byles had seen this day coming as far back as August 1776, when the Committee of Safety had investigated him only a week after Hollis Street Church had dismissed him. With his tendency to joke about the rebels, and with the negative associations of his son’s fealty to the Crown, his position had been made even more tenuous during the winter, when the General Court passed the Seditious Speech Act, empowering rulers now to punish not just deeds but words and thoughts alike. Anyone preaching, praying, or speaking against the American cause faced arrest and fines. Heading the list in February, he was still at the top of it in May. This time, however, the authorities had the sanction of general law behind its list-making; the penalties for an “inimical disposition” could cost him his life and property, which would leave his daughters unprotected. Although certain to be apprehended and tried, he resolved to stay in Boston and protect Mary, Catherine, and his property. Within days, he was brought before a court of special sessions.

The trial occurred on June 2, an unseasonably cold day. Byles dressed both for the weather and the occasion: long black coat, clerical bands, full wig, and hat. Representing himself, he appeared without counsel. He knew that his reputation for punning and making light of Patriot earnestness had brought him to this court room. After all, in 1770, when the riot they now called the Boston Massacre took place, he had famously asked a friend, “Tell me, my young friend, which is better—to be ruled by one tyrant three thousand miles away, or by three thousand tyrants not a mile away?” Still, if he would go down, he would go down as Mather Byles, not as some timid shadow of himself.

Four justices of the peace comprised the court. Byles knew them all: John Hill, Sam Pemberton, Joseph Greenleaf, and Joseph Gardner. They soon gave him an opportunity to disarm them—or dismay them—with a pun. When he entered the room, they motioned him to a seat by the fire. He remarked, “Gentlemen, when I came among you I expected persecution, but I could not think you would have offered me the fire so suddenly.” During jury selection, he objected to a townsman named Fallas, whose name was pronounced “Fellahs.” “Fellows?” He thundered. “I’ll not be tried by fellows!” intending the now archaic meaning of “worthless man or boy.”

Nonetheless, tried he was, and convicted. In case there was any doubt about who was ruling at home, the court sternly issued this warrant to the sheriff: “Whereas Mather Byles of Boston in said county, clerk, stands convicted at Boston aforesaid on the second day of June A. D. 1777 as a person who hath been from the nineteenth day of April A. D. 1775 & now is so inimically disposed towards this & other United States of America that his further residence in this State is dangerous to the public peace and safety. You are therefore in the name of the government & people of Massa [chusetts] Bay in New England hereby directed immediately to deliver the said Mather to the board of war of the State to be by them put on board a guard ship or otherwise secured until they can transport said Mather [Byles] off the continent to some part of the West Indies or Europe agreeable to a late law of said State.”

Perhaps, however, there was some doubt after all. John Eliot, a young Boston patriot aspiring to the ministry and hoping to become Chauncy’s assistant at First Church, wrote to Jeremy Belknap about the trial, scornfully describing Byles’s performance but concluding: “The evidence was much more in favour of him than against him. All that could be proved was that he is a silly, impertinent, childish person. … It was to the great surprise of every one present, as well as to the whole town, that he should be bro’t in guilty. His general character has been so despicable that he seems to have no friends to pity him, tho’ all allow upon such evidence he o’t not be condemned.” Still, if they could convict old man Byles on flimsy evidence—well, watch what you say. Especially if you make people laugh. When Byles was taken to his appearance before the Massachusetts Board of War, its members decided against dispatching him to a prison ship—tantamount to a death sentence—but silenced him by quarantine, changing the sentence to house arrest, imprisoning him at his home, forbidding him to leave the property or receive any visitors, and prohibiting any correspondence.

The Board posted an armed sentry at the house. Byles immediately dubbed the sentry “My Observe-a-Tory.” One hot day, Byles asked the sentinel to bring him a bucket of cold water from the street pump. When the sentry replied that he could not leave his post, Byles told him not to fret, for Byles would walk his rounds for him. Whereupon, he shouldered the young man’s musket and marched smartly up and down in front of the house until the soldier returned from the well. Although his house arrest lasted for two years, the Board of War removed the sentry after two months. Byles then told his family, “I have been guarded, re-guarded, and disregarded.”

Meanwhile, in Halifax

In general terms, his son’s situation resembled that of most Boston Loyalists relocating in Nova Scotia. He realized that the property and belongings he had hurriedly left behind were vulnerable to looting and confiscation. About the evacuation, he wrote: “… it has totally ruined multitudes, who thought themselves perfectly secure in the British protection. Of this number I am one, not being allowed to bring away any furniture, or anything that I possessed, but a couple of beds, with such articles as might be contained in a few trunks and boxes.” Bostonians held a grudge against Mather Byles Jr., a grudge his father’s presence recalled for them every day. Two years after his departure, Massachusetts passed the Banishment Act. His name prominently appeared on the list of those forbidden, under penalty of death, to return. With the Confiscation Act of 1779, his home and belongings were sold at public auction.

After the war, he pressed his claims, and those of his father, for compensation before the Royal Commission on the Losses and Services of American Loyalists, itemizing losses of £800. The Commission gave him £120 and paid for his passage back to Nova Scotia; his father received no compensation from Britain but considerable scorn from Bostonians because of his wayward son.

In one way, however, Mather Byles Jr. was more fortunate than were many other United Empire Loyalists. General Howe had retained him as chaplain to the British regiments posted to Halifax, so he had a salary there. Like other Anglican clergymen, moreover, he also received a stipend as a missionary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, and eventually he obtained regular Anglican positions both in Halifax and ultimately in St. John, New Brunswick. Although he had a price on his head in Massachusetts, and he sometimes called Halifax “the American Siberia,” at least he had some money coming in.

Many other Nova Scotia Loyalists were less fortunately placed, as was his father in Boston, who, of course, then had neither a profession nor a salary. Politically quarantined in his own house, he could not attend worship services, even if any Congregational church would have had him. After the imprisonment ended, Reverend Samuel Parker, rector of Trinity Church, befriended him, and he sometimes attended services at Parker’s Anglican church, but he stuck to his Congregational principles. Parker later related that Byles on his deathbed, with characteristic slyness, whispered, “I have almost got to that world where there are no bishops!”

Mary and Catherine remained unmarried and became seamstresses. Byles could no longer support his then-16-year-old ward, Mather Brown, so, legend has it, he gave the boy his last fifteen dollars and bade him farewell. The lad eventually reached England, studied with Benjamin West and Sir Joshua Reynolds, and became a respected painter of portraits, for a while competing with John Singleton Copley. Byles sold some of his property, lived off a few meager rents paid on property that had been in the names of his two late wives, and, despite a series of strokes, existed for the next eleven years upon the kindness of some brave friends who, despite John Eliot’s assessment, did pity him and did not consider his wisecracking tongue a clear and present danger to the new nation’s peace and security.

Even after their father’s death on July 5, 1788, his daughters never surrendered their father’s house. Mary and Catherine refused to move from the house or sell it. In the 1830s, they each died there, a couple of years apart, and six decades after a civil war that resulted in their father’s loss of his most prized possession: his voice, public and private. In order to achieve home rule, the revolutionary government had ruled aggressively against their family at home. But the two daughters of Dr. Byles, until the days they died, refused to acknowledge either that government or its successors. In their wills, they insisted that nothing the family possessed, from its furniture and their family’s fine library to the family papers, should come into the hands of a citizen of the United States. It was all crated and shipped to their relatives in Halifax. Throughout the presidencies of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, John Quincy Adams, and Andrew Jackson, they remained true to their father and their king, stubborn Loyalists to the end.

The names of the twenty-nine people identified as dangerous are printed in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 34 (1880) 17. See also John Noble, “Some Massachusetts Tories,” Publications of the Colonial Society of America, Vol. 5: 257-59 (Boston, 1902). The list of names is given below. Noble identifies many of these people and indicates, as far as the documentary evidence will permit, the disposition of their cases. In some instances, as he writes, the person “left nothing behind but the shadow of a name.” Noble also prints a record of persons in jail on February 18, 1777. It includes Edwards, Davis, Capen, Brush, and (John) Whitworth. The most prominent name among the prisoners is Dr. Benjamin Church, the infamous double agent. Interestingly, the list of prisoners includes seven women, three of them (Mary Noax [or Voax], Mary Young, and Miss Hill [and daughter]) mentioned by name. Lorenzo Sabine mentions most of the twenty-nine above, but in some cases he can indicate only that they appear on this list. See Sabine, The American Loyalists, or Biographical Sketches of Adherents to the British Crown in The War of the Revolution … (Boston, 1847). I am researching this list as part of an overall effort to construct a profile of the cohort of Loyalists who stayed in Boston, but my work is not yet complete.

Ebenezer Norwood

Mather Byles, D. D.

Benjamin Phillips

Dr. James Lloyd

Daniel Hubbard

Dr. Isaac Rand Jr.

John Tufts

Edward Wentworth

William Perry

Dr. Samuel Danforth

George Lush

Edward Hutchinson

Thomas Edwards

Hopestill Capen

Patrick Wall

Benjamin Davis

Benj Davis Jr.

David Parker

James Perkins

Nathaniel Cary

Richard Green

William Jackson

Samuel Broadstreet

Thomas Amory

Charles Whitworth

Dr. Thomas Kast

John Erving, Esq.

George Bethune

Dr. Miles Whitworth

Further Reading

Carl Becker’s remark about home rule can be found in his book The History of Political Parties in the Province of New York, 1760-1776 (Madison, Wisconsin, 1909). Arthur Wentworth Eaton’s The Famous Mather Byles (Boston, 1914) and the biographical sketch of Byles Sr. by Clifford K. Shipton, reprinted in New England Life in the 18th Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1963), remain the chief sources of information about him. For Mather Byles Jr., see the entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography. For Mather Brown, see Dorinda Evans, Mather Brown: Early American Artist in England (Middletown, Conn., 1982). The fullest accounts of the siege of Boston remain Allen French, The Siege of Boston (New York, 1911) and Richard Frothingham Jr., History of the Siege of Boston and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill (Boston, 1851). David McCullough, in 1776, has a briefer, more recent account (New York, 2005). North Callahan, Henry Knox: General Washington’s General (New York, 1958), has been for a long time the standard biography of Knox, but see also the more recent study by Mark Puls, Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution (New York, 2008). The most influential histories of the American Loyalists remain Wallace Brown, The Good Americans: The Loyalists in the American Revolution (New York, 1969), and Robert M. Calhoon, The Loyalists in Revolutionary America (New York, 1973). The experiences of American Loyalists who traveled to England or relocated there are detailed in Mary Beth Norton, The British-Americans: The Loyalist Exiles in England, 1774-1789 (Boston, 1972). Myra Jasanoff’s Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York, 2011) provides a wide-ranging study of the dispersal at the conclusion of the War for Independence of 60,000 American Loyalists, black and white, throughout the world and of their effect on the eventual extension of the British Empire in the nineteenth century.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.4 (Summer, 2013).