When we encounter this desk as visitors, it is easy to see Nehemiah Bull sitting alone at it. This is perhaps for good reason as the desk was a symbol of his position in the church and in colonial society as well as his authority as male household head. It would also have been a space that he sometimes went for solitude. But while visitors today enter empty homes and are met with a static world, the eighteenth century was far from this. When we repopulate the room, we must consider additional interactions around the desk. Artifacts like the Bull desk recall all types of stories of the diverse people who made these objects and interacted with them. When we bring this world into motion again, we are greeted with a much richer and more diverse view of colonial America.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was carried out thanks to a New England Regional Consortium Fellowship, with special thanks to Dan Sousa, furniture curator at Historic Deerfield, for showing me the desk and the drawer with Bull’s signature. Thank you as well to Karin Wulf, Kristen Beales, and Alison Bazylinski for reading early drafts of this article.

Further Reading

On desks and colonial storage furniture, see Wilson H. Kimnach and Kenneth P. Minkema, “The Material and Social Practices of Intellectual Work: Jonathan Edward’s Study,” William and Mary Quarterly 69 (Oct. 2012): 684; Gerald W. R. Ward, “The Merchants’ Real Friend and Companion” in Boston Furniture, 1700-1900, ed. Brock Jobe and Gerald W.R. Ward (Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2016), 166-179; A Place for Everything: Chests and Boxes in Early Colonial America (Winterthur, Delaware: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 1986); Brock Jobe and Myrna Kate, New England Furniture: The Colonial Era (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984).

On the Nehemiah Bull desk, see Katherine Fecteau, “It’s a Bird! It’s a Plane! It’s … a table-desk” Past@present blog, Umass Amherst Department of History, https://umasshistory.wordpress.com/2016/07/25/historic-deerfield-internship/; “An Historic Desk from Before Desks Were Desks” The Appraisal Group, https://appraisalgroupusa.com/an-historic-desk-from-before-desks-were-desks/; Robert Rober, “Besides historic desk, Rev. Bull owned people,” Daily Hampshire Gazette, April 25, 2016 https://www.gazettenet.com/Romer-letter-1612543.

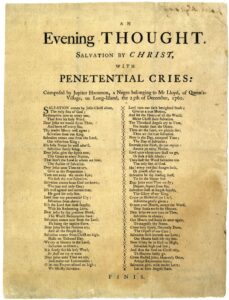

On Nehemiah Bull’s involvement in Stockbridge, see Patrick Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992). On Bull as teacher to Jupiter Hammon see Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1683 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 66.

On manuscript culture in early America, see Catherine La Courreye Blecki, “Reading Moore’s Book: Manuscripts vs. Print Culture and the Development of Early American Literature,” in Milcah Martha Moore’s Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America, ed. Catherine La Courreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 59-106.

On slavery in Deerfield and western Massachusetts, see Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, Mr. and Mrs. Prince: How an Extraordinary Eighteenth-Century Family Moved out of Slavery and Into Legend (New York: Harper Collins, 2008); C.S. Manegold, Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010); Robert H. Robert, Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts (Florence, Massachusetts: Levellers Press, 2009); Marla R. Miller, Entangled Lives: Labor, Livelihood and Landscapes of Change in Rural Massachusetts (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2020).

On enslaved people and space, see Dell Upton, “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia,” Places 2 (no. 2, 1984): 59-72; Bernard L. Herman, Town House: Architecture and Material Life in the Early American City, 1780-1830 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005); John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); Rhys Isaac, The Transformation of Virginia 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture, 2012; 1999); Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004); Marisa Fuentes, Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2006).

This article originally appeared in September, 2022.

Caylin Carbonell is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History & Culture. She is a historian of race, gender, and power with a focus on the lived experiences of unfreedom in early New England. Her book project, Laboring Lives: Households, Dependence, and Power in Colonial New England, uses innovative archival practices to reveal stories of the everyday lives of diverse New Englanders.