A Note on Early American Music Studies: Introduction to Common-place 13:2

In the last few years, scholarly interest in American music before the twentieth century has increased as the focus of interdisciplinary articles and dissertations, and this is a most welcome development for all of us who have specialized in topics relating to music in early America. Part of this resurgence comes from a revival of early American studies from within musicology as well as an expansion of enthusiasm for historical music performance. Perhaps the defining characteristic of this trend, however, is the extension of boundaries that previously circumscribed academic fields of study. This issue of Common-place offers a sampling of some of the most recent research being conducted by specialists from musicology, religion, history, English literature, geography, American studies, dance/theater, and music performance. The range of fields is significant not only because this work has generally broadened the purview of these other disciplines but also because new perspectives of inquiry have moved from an approach based somewhat narrowly on the music itself to aspects of what music historically represented to its practitioners and consumers.

In the 1950s and 1960s, an earlier generation of musicologists published groundbreaking analyses of early hymnody and music production that set a high bar for widely read research in the relatively overlooked field of indigenous American music. The work of Richard Crawford, Alan Buechner, H. Wiley Hitchcock, Irving Lowens, Nicholas Temperley, Nicholas Wolfe, and their graduate students helped to expand a vibrant sub-field within musicology that has endured through the efforts of organizations like the Oscar Sonneck Society for American Music. From a historiographic perspective, the best of this work strove for a synthesis of musical styles, influences, and context in addition to more specific deconstructions of musical notation and musicians’ biographies. Besides a small library of monographs and articles, several compendiums of early American sacred and secular music were compiled. For instance, Crawford’s core repertory is a “top 100” of sacred tunes published in America based on printing frequency, assembled in the same era that Billboard Top 100 listings for popular music began to be broken down by genre within the American music industry. Temperley’s hymn tune index is a comprehensive database of English language hymn tunes that helps identify composers, texts, and publication history through a variety of references including tracking the first five notes of any given melody. Significantly, this latter search engine makes accessible a great deal of specialized scholarship to those with minimal music reading ability and is a great boon to even casual owners of pre-1820 hymnals, often missing title pages or indexes, in identifying publications and songs. The fruits of these scholars’ labors have been indispensable for continuing research.

However, as recently as 2005, an opinion essay in the Bulletin of the Society for American Music, the principle musicological organization for Americanists, asked “What Happened to the Nineteenth Century?” and noted a paucity of young musicologists choosing subjects from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a trend that apparently started in the 1970s. The essay suggests that the cause of this lapse was not from a constriction of opportunity or limited vision, but rather an unintended consequence of the success of the society in fostering interest in popular music. Initially understood as a twentieth-century secular phenomenon, scholarly attention to commercially successful music that often marginalized music literacy, rather than eurocentric art music, was an aesthetic sea-change within the study of music with enormous appeal for young students. In addition, the benefits of studying and teaching to non-specialists musical topics with available sound recordings and moving pictures, as opposed to those without, can well be imagined.

Ultimately, however, the omnipresence of sacred music in early euro-American culture, in and outside of churches, has come to be seen as the popular music of its time by every definition but secularity itself. Its printing and dissemination offered financial opportunity; tradesmen sang hymns while they worked, and many people had favorite, nostalgic hymns they treasured for a lifetime; some populist denominations used contrafacta, or melodies taken from well-known secular songs, in crafting texts for new hymns; stylistic changes came through experimentation with other new forms of music (from theaters, recent immigrants, new mechanical technologies, etc.); music literacy was simplified through a plethora of shape-note systems (a.k.a “dunce notes”) and numeric or letter substitutions for conventional music notation; singing schools for young people met in the middle of the week outside of the church, where new ways of singing that would offend older parishioners could be tried; in some denominations, instruments were gradually introduced, making performance in public more sophisticated; and particularly in the northeast, just about any man with an interest and aptitude in music could establish a reputation as a publishing composer of hymns. Along with the secular folk tradition, early popular music was fair game for any scholar interested in popular culture.

As these new trends were underway in the 1980s and 1990s, other liberal arts such as history, American civilization, and literary studies were being influenced by cultural anthropology in ways that made revealing the process of cultural formation a defining component of research. Positioning courses of study that extended into other fields was a natural consequence of the redefinition of former categories within these disciplines. Researchers who lacked intensive musical training, and previously may have been intimidated, or put off, by the perceived requirement of a grounding in music theory and composition, now felt fully qualified to assess historical music as a cultural artifact. And of course providing the gamut of contexts for specific musical expressions in America’s past makes them all the more comprehensible, and conveys an appreciation for the ubiquitous importance music had for people long before the age of electronics.

Research has also been encouraged by the realization that music is not just a reflection of culture, it is an essential part of cultural production in one of its most protean, humanistic forms. Closely related to language, music is a universal human activity that antedates civilization and perhaps even speech itself. Recent neurological and paleo-humanities studies, such as Daniel J. Leviton’s This Is Your Brain On Music, Steven Mithen’s The Singing Neanderthals, and Oliver Sacks’s Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, have collectively posited that the human capacity for music is a much more complex and widespread component of the brain than previously understood; or rather, they have sought to substantiate what has long been surmised by many thoughtful music theorists through the ages. Many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century American religious tracts pointed to sacred music’s ability to create an atmosphere of sublime transcendence, to cool passions such as melancholy, anger, fear, or grief to a Christian equanimity of acceptance. By the early nineteenth century, however, secular claims for music’s benefits were being rediscovered. For example, an 1804 dissertation on “The Influence of Music In The Cure of Diseases” by a graduating medical doctor at the University of Pennsylvania notes that his opinions “will excite the risibility of many … [but] that its originality entitles it to some degree of notice, and that future investigation of the subject will, no doubt, give it that place in the Materia Medica which it merits.” His theory was based on observations of the calming effect music had on mentally disturbed patients but he hoped to extend the hypothesis to physical disorders.

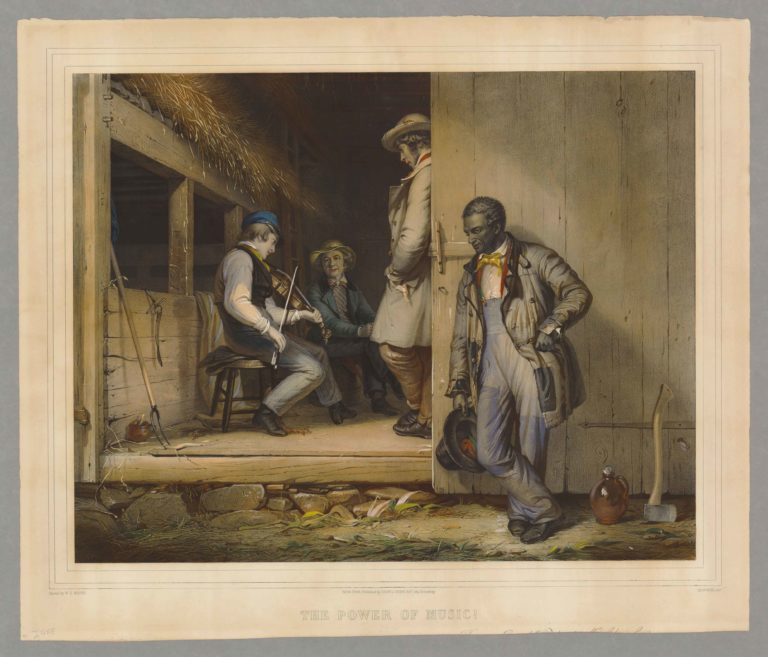

Several of the essays in this issue touch on this nearly magical capacity of music, and the intimately related ritual of dance, as ways of better imagining historical events, and an alternate means of cross-cultural communication. The reciprocity between melody and dance rhythms, as well as the Irish and African immigrants who exchanged them in mid-nineteenth century America, is highlighted in April Masten’s complex exploration of competitive popular dancing. The efficacy of this non-verbal cultural traffic, which exists alongside, and outside, archival historiography, is further highlighted by her impressions of current reproductions of Negro jigs performed at a recent music conference. Masten also includes extensive discussion of instrumental performance practice and interchange as well as glimpses of audiences and venues for this widespread vernacular entertainment that has received little explication.

In Jeanne Eller McDougall’s series of early musical encounters between English colonists and Kikotan natives in 1609 Virginia, she expands on brief mention of the presence of instruments and musicians in documents recording some of the earliest interaction between Europeans and Powhatan natives to flesh out the importance that each culture placed on various uses of music. The wonderment and strangeness that the music of each culture wrought in the other becomes our own as she parses the social assumptions evident, particularly in the extant English reports. Clearly, each culture’s music is being deployed in the name of diplomacy, deceit, and even conviviality in ways that augmented or replaced the shortcomings of language.

Christine DeLucia’s piece presents a similar contrast between Native and English musicality but firmly locates this confrontation in southern New England. Here, Puritan psalmody conveyed a religious solidarity more akin in purpose to the spiritual chanting of their native neighbors than the martial music of their Jamestown countrymen. However, she traces the continuation of musical interplay between cultures from the eighteenth century to the present, highlighting musical memorials of King Philip’s War. Like a metaphor for their cultural survival, Narragansetts and Wampanoags early on consciously incorporated European musical forms with their own traditions to succeed in conveying their history to the American public.

In a similar use of music as a mnemonic device, Nikos Pappas makes the case for seeing and hearing an 1868 southern hymnal as a solemn reverie for the lost cause of the Confederacy. Papas presents a close reading of the names that Rigdon McIntosh, the compiler and composer of some of the hymns, used to memorialize camps, battles, and officers he knew personally that commemorate his experience as a soldier during the war. He provides a revealing explication of the biblical symbols used by McIntosh on the cover illustration, demonstrating once again that contextualizing cultural artifacts is crucial in recovering meaning that can quickly be lost on later generations unversed in scripture. Pappas makes us aware of the southern audience to which this hymnal is addressed, distinguishing it from other American audiences characterized by region, class, or musical sophistication. By showing how singular this particular collection was we also discover something about how vibrant the mainstream American market for hymnody was.

Nara Newcomer’s article delves into unscrambling a century-old controversy over the authenticity of a manuscript hymnal purportedly signed by John Wesley from the early 1700s. It is also this issue’s nod to the importance of historical manuscript music which reflects an individual’s favorite pieces: an eighteenth-century playlist, if you will. Handwritten music and/or texts were a ubiquitous and inexpensive mode of communal music transmission that could anticipate, copy from, or circumvent printed dissemination. Five line staff markers, for making one’s own blank music paper, were available in most music stores in Britain, even though the first known business dedicated to music didn’t exist in the American colonies until 1768. In the case of the pseudo-Wesley manuscript, personal preferences, like the absence of fuging tunes, help to establish where original owner and psalm singer Ralph Potts situated himself in the controversies that raged in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century hymn aesthetics; and the presence of a single tune that Wesley publicly condemned adds to the evidence that he had nothing to do with the manuscript.

Handwritten music figures prominently in Carol Medlicott’s piece where the idiosyncratic style, music notation, and purpose of Shaker song and dance demonstrate how one of the best known utopian societies in the early nineteenth century customized music to its daily regimen. Shaker music is clearly an ethnomusicologist’s dream: an isolated, tight-knit community with worship and dance traditions that are so different that outsiders flock to witness them; a music notation system that is so radically different that it remains indecipherable for over a century; and a literate society with extensive repositories of both music and letters that discuss their worship and beliefs. At the same time, Medlicott traces the musical ways in which such a proselytizing sect nonetheless could be influenced by trends in mainstream American sacred music. Perhaps the most fascinating feature of the Shaker use of music, and its relationship to fundamentally human needs, is the uniformity of worship and sense of community it could engender over such a wide geographic area.

Two of our essays in this issue center on the rapidly expanding American market for indigenously printed secular music starting in the 1790s, and its penchant for political argument and satire. Myron Gray concentrates on three songs of French derivation printed by Benjamin Carr, one of the best known and most prolific musician/publishers of the early republic. His choice of controversial songs of the French revolution in America details their positioning between the emerging two-party system of Federalists and Democratic Republicans. Musicologically speaking, it directly addresses the nexus of comparisons between a song’s original intent and construction, and its repurposing in a different social context while still retaining some of its original meanings. Glenda Goodman gives us a thick description of how an English popular song, “Derry Down,” with a rich pedigree in street culture adaptability stretching back to the seventeenth century, was widely employed in American political prints of the late 1790s to decry the attempts of revolutionary French diplomats to bribe emissaries of the new American republic. In both essays the influence of the human voice is an important undercurrent to the alterations made to the music itself. In the case of “Derry Down,” the melody acquired syncopation and high-note emphases at phrase ends as it passed through its use in English ballad operas of the mid-eighteenth century. This effect accented key words on the London stage but complicated its suitability for easy singing off the pages of American newspapers. In both cases, later American adaptations moved away from their originally comfortable use within most people’s vocal range. “La Marseillaise,” “La Carmagnole” and “Ça Ira” were each envisioned by Carr as theater entertainment or in a parlor piano setting where singing was peripheral to the project. This points to important shifts in the American music scene that immigrant European professional musicians were implementing in the 1790s. The wide popularity of the tune “Derry Down,” when used as a vehicle for political satire, appears to have been more important than its ability to be sung; but it is also quite possible those responsible for adapting the words to the tune were not musical.

While musical exegesis can be fine-pointed and narrowly targeted, the revelation of historically derived meanings have implications far beyond music’s technical arrangements. Every one of these essays has, at least, that theme in common. Musical change over time, both in the construction of early American song as well as the values with which audiences and performers imbued it, are worth discovering as ways of intelligibly complicating the way we come to know our cultural heritage. We hope you enjoy these essays as much as we have.

This article originally appeared in issue 13.2 (Winter, 2013).

Peter S. Leavenworth is an independent scholar, writer, professional musician, and master carpenter from Madbury, New Hampshire. He is currently working on publishing his research in American popular music of the early national period, Accounting For Taste: The Early American Music Business and Popular Aesthetics in the Early Republic.