A Short History of the High Roll

By age twelve, Anna Green Winslow knew what it meant to suffer for beauty. The year was 1772, the place Boston. In April, Winslow expressed in her diary an appetite for the “tasty head Dress” she spied on a fashion doll, reproduced from a recent London print. One month later, she had her own head dressed in a similar fashion. The “famous roll” she wore was composed of “red cow tail, horsehair, and a little human hair . . . all carded together and twisted up.” She noted with delight that, with the “roll” perched atop her young head, she measured a full inch longer from the roots of her hair up to the tip of the style than from her forehead down to her chin. But Winslow’s pleasure at her appearance was tempered by the fact that the style made her head “itch and ach and burn like anything.” No wonder–such rolls often weighed almost a pound. Adding insult to injury, one of her disapproving aunts said the roll ought to be made smaller, while the other drolly rejoined that it “ought not to be made at all.” To appease them (for she often read her journal entries aloud) Winslow penned the following, which reads like a maxim plucked directly from a conduct manual: “Nothing renders a young person more amiable than virtue and modesty without the help of fals hair, red cow tail or D____ (the barber).”

The tugs of filial duty and fashionability, Winslow found, were powerful and often contradictory. Such was the tension between high fashion and feminine propriety in the eighteenth century, between expressions of status dependent on the mode and its proponents, and those based on inherent “taste.” The hairstyle Winslow donned had not yet reached its height; in fact, the high roll was just beginning its ascent. Chronicling the rise and fall of the fashion takes us from the courts of France to the printshops of London and finally to the streets of Philadelphia in 1778, where all that the high roll represented in a new nation at war with an old empire was brought quite literally to a head.

“Fashionable” hairstyles for women began their vertical climb in the late 1760s, and with them rose the ire of social critics. Editorials appearing in London periodicals immediately decried the large headdresses that English ladies were all too eager to copy from their French counterparts. Yet other printed essays and treatises described in detail the latest hair fashions from France and how to achieve them with the assistance of a hairdresser, or friseur. These instructions, coupled with the presence of hairdressers hailing from England and France, helped speed the spread of the high roll to colonial cities. Like most styles in fashion in England, the high roll was quickly adopted by elite women in the colonies.

The outcry against it proved equally swift and sharp. In 1767 the author of a letter to the editor of the New York Journal bemoaned the fashion that led women to double the size of their heads with the use of pomatum, artificial pads, and hair procured from corpses. But most distressing of all, the writer claimed, the “frizzled” style resembled the “shock head of a Negro.” The insult was twofold, for the so-described “shock head”–the combing and bunching of hair high over the forehead–was a style worn by African American men, free and enslaved. Not only did the writer deploy a racial category to mock women’s appearance, he also questioned the femininity of those who chose to sport the new fashion.

Despite such searing criticism, into the 1770s the roll grew in popularity as well as height among colonial women who considered themselves fashionable but also tasteful. Philadelphia belle Sarah Eve, educated and genteel, wore her hair high, complaining in 1772 that the social kissing practiced by Edward Shippen “disorders one’s high Roll.” It took some time for a hairdresser to create such a style, so having it “disordered” was of no small inconvenience. Women might have their heads labored over for hours on end. The amount of time involved in achieving the elaborate look meant that wearing a high roll signified high social status in two ways: not only did it replicate a style worn at court and by female members of the beau monde in England, but a woman needed plenty of spare time in order to have it constructed. The image of the big-haired, consumer woman of leisure, sitting for hours in the service of her own vanity, flew in the face of an ideal that featured the modest, domestic, and productive colonial woman virtuously spinning cloth to support recently ended boycotts of English goods.

Furthermore, obtaining a high roll required women to spend time more or less alone with hairdressers, men often of European origin and questionable lineage. Charges of unbridled appetite and inappropriate sexual encounters with their coiffeurs served as another means of discrediting women who sported high rolls. Underlying this preoccupation were anxieties over relationships between men and women of different social ranks, and potential dependency of women with means on men without. It was the strange fate of hairdressers and other purveyors of fashion to produce markers of high status within a social hierarchy that assigned them low rank. Yet these men nevertheless claimed more than a little power and authority. In 1776 the Lady’s Magazine lamented that “powdered and embroidered” hairdressers could be seen stepping in and out of coaches all over London. One peruke maker from New York attracted female clients with promises of performing the “true method of making the deservedly celebrated hollow toupees or tates,” which he claimed were “held in such high estimation that few ladies would choose to be without them.” Every woman would wear one if she could afford to do so, the notice implied. The advertisement at once legitimated the style itself (“deservedly celebrated”) and questioned the taste–and the financial wherewithal–of those who did not don it.

Bolstered by such come-ons to counter the moralizing naysayers, the high roll persisted, as hair fashions became even larger and more fantastical with the ascension of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette to the French throne in 1774. The queen added plumes to her already high head, a fashion imitated in England and the colonies. Incorporation of feathers caused the “towers” to reach over two feet in height. Although that same year the newly formed Continental Congress passed a resolution against extravagant attire, mourning dress in particular, proscribing a feminine hairstyle would have invested it with far too much power, elevating the high roll from the status of “frivolous” fashion to that of political problem. Lampooning and satire, then, remained the chief weapons marshaled to defeat the style in the court of public opinion. A poem in the Pennsylvania Evening Post in June of 1775 mocked the “preposterous fashion of the ladies wearing high plumes of feathers in their heads.” The problem, according to the piece, was that plumes too closely resembled military headdresses, and therefore “martializ’d,”–read, masculinized–the women who wore them.

This was not the first time gender-bending heads had come under attack. Generally, the trend in men’s hair from the 1760s was toward a more “natural” look, while women’s headdresses were noticeably artificial. However, one widely satirized element of the male “macaroni” fashion of the early 1770s was a large wig that supported a comparatively tiny cap. The style resembled women’s headdresses also in vogue, and macaronis were constantly castigated as effeminate. Whether macaroni wigs or women’s plumes, any fashion that disrupted increasingly fixed understandings of “masculine” and “feminine” was suspect. The Lady’s Magazine called the wearing of false hair “inconsistent with that delicacy which is, or ought to be, characteristic of the fair sex,” and recommended that women set “an example of modesty and virtue to their inferiors, rather than a towering head.” Prescriptive literature urged the avoidance of extremes in appearance as well as behavior for men and women alike. Balance and restraint had become elements of good taste that signified membership among the virtuous “middling sort.”

Yet the same Lady’s Magazine that condemned extreme versions of the high roll included in July of 1777 a plate of the “last new Ladies head-dress a la Zodiaque,” which contained replicas of the moon, stars, and all twelve astrological signs. The illustration was not a lampoon. The accompanying text read, “[W]e are glad to have it in our power to furnish our readers with the . . . newest head dresses.” A variety of ornaments decorated women’s heads in the mid-1770s, rendering high rolls all the more extravagant. One “lady of fashion” reported to the Pennsylvania Gazette in 1776 that some hairstyles spotted in London reached over a yard in height, including lengths of colored gauze, feathers, and, to top it all off, an entire artificial salad complete with carrots and radishes. Yet another high roll was bedecked with a miniature sow and six suckling pigs. It seems unlikely that many women actually wore replicas of animals and vegetables in their hair. What is more probable is that some editors mockingly featured these extreme examples in order to counter fashion periodicals and shame women into rejecting the style altogether.

The “stuff” that cropped up in women’s headdresses found satiric expression during the early stages of the American Revolution. Soon after war broke out, London printshops retaliated, employing images of the high roll in order to mock upstart colonials. Prints such as Bunker’s Hill, or America’s Head Dress, show British troops trudging up the side of a high roll toward their stronghold opposite the American army’s “hill.” The image likened the colonial cause and military effort to the elaborate hairstyle: hollow, artificial, and short-lived. Another print entitled Miss Carolina Sullivan, one of the obstinate daughters of America, depicts an unattractive woman sporting a towering head of hair replete with tents, flags, cannons, and even a replica of a hanged man, mocking Americans’ ridiculous pretensions of refinement as well as independence. Such prints altered and yet extended European images of the feathered Indian maiden that allegorically represented a feminized, dependent America. Yet they also took aim at the hairstyle itself–and at its English devotees. Did English women wish to look like the absurd, provincial Carolina Sullivan?

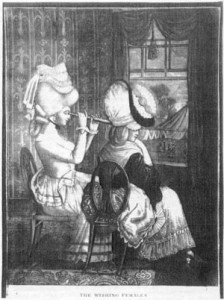

On the American side of the Atlantic, supporters of the patriot cause and “Tory” women alike found uses for the high roll. In 1777, after two hard-fought battles, British General William Howe’s army captured Philadelphia, and would occupy the city for eight months. It was a time of want–high prices for food, fuel, and goods–and of deep patriot dismay over the fallen city and the uncertain loyalties of its Quaker residents. In the midst of the occupation, an engraving entitled The Wishing Females suggested what at least some American men feared and loathed–that high status women of Philadelphia directed romantic interest toward and threw social weight behind the occupying army. The image depicts two women in high rolls gazing longingly out their parlor window at British officers and regulars. One smiles knowingly as she peers through a looking glass, closely inspecting the troops in the field. The other dreamily contemplates the men, chin on hand. They appear to be sexual predators, ready to leap from the interior, domestic space to cavort lasciviously in the external realm of military men.

Patriot suspicions of “alliances” between Philadelphia ladies and British soldiers were further confirmed by the Meschianza, an elaborate fete staged in May of 1778 to honor the departing British army. Many “belles” participated, each attended by a British officer or “knight” who competed in medieval-style jousting tournaments in her honor and for her affection. Hannah Griffitts poetically cast the Meschianza as a “shameful scene of dissipation, the Death of sense and reputation,” regretting that “ladies joined the frantic show.” Major John André orchestrated much of the event, down to circulating a sketch of how he wanted the women’s hair and dress to appear. It seemed to some that Philadelphia’s ladies were taking fashion advice from a British officer, molding their very persons to his desires and specifications. Josiah Bartlett, delegate to the Continental Congress from New Hampshire, supported this opinion, as well as the message of The Wishing Females, in a letter to his wife composed in the summer of 1778. He wrote that when Congress arrived back in Philadelphia, “they found the Tory ladies who tarried with the Regulars wearing the most enormous high head Dresses after the manner of the Mistresses and Whores of the British officers.”

When high-haired women dared to appear in public on July 4, 1778, Independence Day, the high roll took on a starring role in street theater against the backdrop of a city rife with social and political tension. Although descriptions of the incident vary slightly from account to account, the discrepancies help to demonstrate the episode’s import. In the words of Josiah Bartlett, “some Gentlemen purchased the most Extravagant high head dress that could be got and Dressed an old Negro Wench with it.” The woman was then “paraded around the city by the mob,” making “a shocking appearance to the no small mortification of the Tories and Diversion of the other citizens.” Delegate Samuel Holton, however, supposed the woman to be a “strumpet,” employing a sexual epithet but no racial designation. Thomas Bradford, some fifty years later, remembered the figure not as a woman at all, but a man–adding yet another layer to this world-turned-upside-down. In terms of the performance’s intended messages, all recollections could be considered symbolically correct. At the expense of a single victim, the episode mocked all women who wore high rolls, casting them as politically disloyal, black, unchaste, masculine, and of low status, completely inverting the wealth and feminine beauty that women who wore high rolls felt the style signified. Yet it was also designed to humiliate loyalist men by attacking the characters of women associated with them. According to Bartlett, “gentlemen” who could afford to purchase such a headdress perpetrated the incident, matching the extravagant and effete display of the Meschianza with their own rough and ribald show. In doing so, they proclaimed that dependence on the vagaries of feminine, Old World fashion and luxury would not be allowed to undermine what they hoped was an enduring American project.

People are often inclined to mock and regard as abhorrent what feels dangerously similar or close, producing difference and distance through satire. For the “gentlemen” who initiated the Independence Day scene, high-rolled women embodied anxieties about their own vanity, dependence, and the ways in which hierarchies of status and gender would operate in a country untethered from its colonial moorings, and in a colony suddenly become a masculinely democratic state. A coda to the apparently final movement in the high roll symphony reveals that the style did not die an unnatural death at the hands of a Philadelphia mob. One year later a series of editorials in the U.S. Magazine debated the propriety and attractiveness of women’s headdresses, and in 1781 visiting French minister Abbé Robin noted the outréhigh hair worn by the American women he met.

Today as in the eighteenth century, big hair still carries a certain charge, whether Angela Davis’s Afro or Ivana Trump’s blond helmet. If you doubt that ideas about gender, class, and politics can be sprayed atop a female head, remember the film Working Girl, in which the protagonist lops off her teased Staten Island locks with the declaration, “If you want to be taken seriously, you need serious hair.” People adorn themselves to meet the approval of particular audiences, wearing styles that other viewers may not appreciate, might even mock or reprove. While today’s fashionistas and mesclun-crunching Bobos may disdain big hair, plenty of women continue to wear it, secure in their own taste. Yet for every modern-day Anna Green Winslow pleased with her appearance, there exists a stern aunt or angry crowd poised to attack the very symbols of that pride. The meanings of hairstyles are as myriad and mutable as the identities of individuals who don and gaze upon them, giving fashion an internal logic in the truest sense.

Further Reading:

Primary material for this essay was taken from Alice Morse Earle, ed., Diary of Anna Green Winslow, A Boston School Girl of 1771; Eva Eve Jones, ed., “Extracts from the Journal of Miss Sarah Eve,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 5 (1881) 19-36; John Fanning Watson’s scrapbook, compiled in 1823 as he researched Annals of Philadelphia, and bound issues of the Lady’s Magazine, which began publication in London in 1770, all in the collections of the Library Company of Philadelphia; the New York Gazette and the Pennsylvania Gazette; and Letters of the Delegates to the Continental Congress, Library of Congress CD ROM edition.

The introduction to Ingrid Banks’s Hair Matters: Beauty, Power and Black Women’s Consciousness (New York, 2000), a sociological study of the politics of women’s hair in African American communities, deftly reviews international scholarship and theories on hair and hairstyles from Sigmund Freud’s 1922 essay “Medusa’s Hair” to Off With Her Head: The Denial of Women’s Identity in Myth, Religion and Culture, Howard Eilberg Schwartz and Wendy Doniger, eds., (Cambridge, Mass., 1995). Grant McCracken’s Big Hair: A Journey into the Transformation of Self (Toronto, 1995) is a lively riff on the power of hair in the late twentieth century. Descriptions of French and British women’s hairstyles in the 1770s are most easily found in histories of eighteenth-century costume, notably Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715-1789 (New York, 1984) and Dress and Morality (New York, 1986), both by Aileen Ribeiro, as well as Madeleine Delpierre’s, Dress in France in the Eighteenth Century (New Haven, 1997). Catherine Howey’s unpublished paper “Feats of Man or Freaks of Nature? or; Hairstyles for Women in the 1770s,” reviews the sentiments of English social critics and fashionable women in debates over high hair.

Among a wealth of fine scholarship that considers the intersection of gender, status, fashion, and consumption in eighteenth-century England see Erin Mackie, Market á la Mode: Fashion, Commodity and Gender in The Tatler and The Spectator (Baltimore, 1997); Margaret R. Hunt, The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender and the Family in England, 1680-1780 (Berkeley, 1996); Amanda Vickery, “Women and the World of Goods: A Lancashire Consumer and Her Possessions, 1751-81” in Consumption and the World of Goods, John Brewer and Roy Porter, eds., (London, 1993); and G. J. Barker-Benfield, The Culture of Sensibility: Sex and Society in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Chicago, 1992). Charlotte Sussman’s Consuming Anxieties: Consumer Protest, Gender, and British Slavery, 1713-1833 (Stanford, Calif., 2000) adds a focus on the rhetoric of race and the consequences of colonialism. For a discussion of hairdressers that has shaped my interpretation see Don Herzog, Poisoning the Minds of the Lower Orders (Princeton, 1998).

Karin Calvert’s essay “The Function of Fashion in the Eighteenth Century” in Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century, Cary Carson, et al, eds. (Charlottesville, Va., 1994) supplies an important analysis of the role of fashion in expressions of social status in early American society, while David S. Shields’s Civil Tongues and Polite Letters in British America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1997) assesses the place of gender in the construction a polite and fashionable beau monde. For descriptions of African American hairstyles of the period see Shane White and Graham White, “Slave Hair and African American Culture in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,” The Journal of Southern History 61 (1995): 45-76. John Fanning Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 1830) contains early nineteenth-century recollections of men’s and women’s Revolutionary-era hairstyles and attire, as well as an account of the Meschianza.

On the cultural significance and politicization of goods and their consumption during the period of the American Revolution, see T.H. Breen, “‘Baubles of Britain’: The American and Consumer Revolutions of the Eighteenth Century” also in Of Consuming Interests, and Barbara Clark Smith, “Social Visions of the American Resistance Movement” in The Transforming Hand of Revolution: Reconsidering the American Revolution as a Social Movement, Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert, eds. (Charlottesville, Va., 1996). For the role of white women in colonial boycotts of British imports see Linda K. Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1980) and Mary Beth Norton, Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Boston, 1980). Karin A. Wulf’s introduction to Milcah Martha Moore’s Book: A Commonplace Book from Revolutionary America, Catherine LaCourreye Blecki and Karin A. Wulf, eds. (University Park, Pa., 1997) provides a good description of Philadelphia society during the war years, particularly while occupied by the British army.

This article originally appeared in issue 2.1 (October, 2001).

Kate Haulman is a doctoral candidate in history at Cornell University, where she is completing a dissertation on the politics of fashion in eighteenth-century Philadelphia and New York City.