The Religious Society of Friends advocated a “guarded education” for their children. This format taught them basic skills (reading, writing, and ciphering) but protected them from worldly influences. The education of Quaker children was to be “useful” and “practical” based in moral instruction. Students learned to “regulate every thought and action” to comply with Quaker ideals of plainness in dress, speech, and deportment. Young Friends were to respect their parents, guardians, and teachers and to live harmoniously with their siblings and schoolmates.

The Friends safeguarded their children by founding Quaker educational institutions in England, British North America, and the United States from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. Sarah Tuke Grubb, a Quaker minister and educator embodied the Friends’ approach to a “guarded education.” She asserted that “a religious improvement in the minds of youth” was the principal aim of Quaker schools. Quakers published specialized books for children both for instruction in the classroom and at home. These publications used Quaker theology and practice to teach basic skills. Lindley Murray, an American Friend, wrote English Grammar, Adapted to the Different Classes of Learners in 1795, which combined “moral and useful observations with grammatical studies.” By learning grammar, young minds would be exposed to the “animating views of piety and virtue.” For example, in the section on parsing, he presented phrases such as “let us improve ourselves” and “virtues will be rewarded,” to merge ethical instruction with language acquisition.

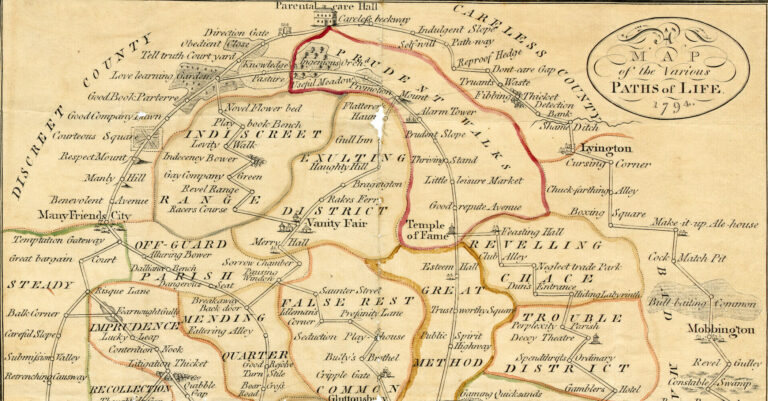

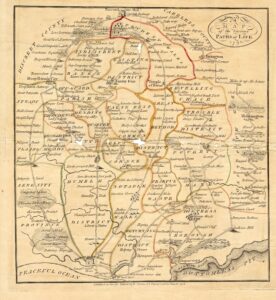

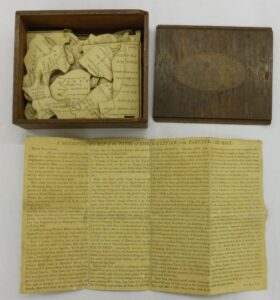

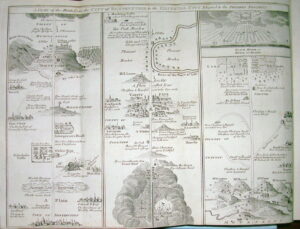

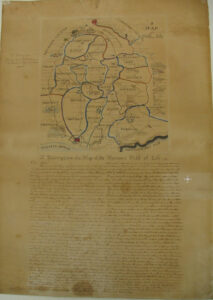

Lockean theories of education also impacted Quakers. John Locke’s treatise, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, became a standard text for childrearing, and it had a profound impression on English and American parents in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Locke believed learning for children should be based in play. This prevalent theory of education initiated the production of material objects specifically for children’s use, and maps became a primary teaching tool in the eighteenth century. Booksellers and printers responded to the growing demand for maps by specializing in products for young consumers, such as atlases, map games, playing cards, and puzzles. Thus, children acquired knowledge by playing with geographic objects.

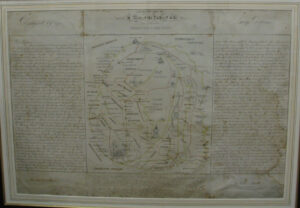

Children’s interaction with the map is evident in the copies made by scholars at the Westtown Friends School in Chester County, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1799 by Philadelphia Quakers, Westtown was a “select” institution that only admitted Friends who were taught by Friends. The school’s archives contain copies of the map made by scholars. In 1826, Matilda Hogdson, a student from Philadelphia, drew the map; in 1828, Mary Hoopes copied the letter in the wake of the Hicksite Schism, possibly to remind her fellow students of the need for tolerance and unity. In the 1860s, Edwin Thorpe attended Westtown as a teenager. He stayed on at the school as an instructor of Writing and Drawing and, at some point, he sketched a copy of the map. In 1872, he became the first faculty member hired to teach fine art at Westtown. As Quaker institutions evolved, and with their entry into higher education, Friends’ attitude toward art changed. As a visual representation of spiritual practice, Dillwyn’s allegorical map, as a successor to the map of Pilgrim’s Progress, drew upon a popular format to expand the means of the moral instruction for young Quakers in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America.