The Advice Jefferson Never Received: Health Counsel Delivered to Jefferson From His Italian Friend Filippo Mazzei, Two Hundred Years Too Late

Two years had passed since my discovery of a mystery letter in a Florence archive, and as I studied the correspondence on the Founders Online website run by the National Archives and the University of Virginia Press, I finally began to comprehend the significance of my accidental find. The letter, dated 1812, written in Italian and, according to the archival reference sheet, directed to “?”, did indeed have a recipient, and a notable one at that. I realized that I had inadvertently stumbled upon a missing link in the extensive chain of correspondence between Thomas Jefferson and his friend Filippo Mazzei (1730-1816), Italian patriot of the American Revolution, who first arrived in Virginia as an agriculturalist in 1773. It struck me that over the course of 200 years, no one had read Mazzei’s letter of 1812 and Jefferson’s letter of the previous year side by side except for Mazzei himself. And now, me. With this realization, I found myself in the throes of my own “archive fever,” consumed by my letter and the mystery that surrounded it. I wondered if this 1812 letter had ever left Italy, and why no one had found it before I did. The clues were there, and I couldn’t resist diving headfirst into a bit of historical detective work.

I stumbled, unknowingly, upon this hidden treasure as a result of a chain of events that can only be described as serendipitous. In June 2015, after co-directing the Bucknell University Engineering in a Global/Societal Context course in Italy, I reserved a day in Florence to conduct archival research on Carlo Bellini, father of Italian Studies in the United States. Friend to both Jefferson and Mazzei, Bellini, originally from Florence, was appointed by Jefferson in 1779 to teach Italian, French, Spanish, and possibly German at the College of William and Mary, a position which he held until his death in 1804. It was at William and Mary that I began studying Italian in the fall of 1991 as a first-year student, and when I heard the story of Bellini at a language conference in 2014, I decided that I owed it to his ghost to find out more about him and his life in the early years of our republic. So, on a cloudy day in June 2015, I set out for the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze in search of an original Bellini document.

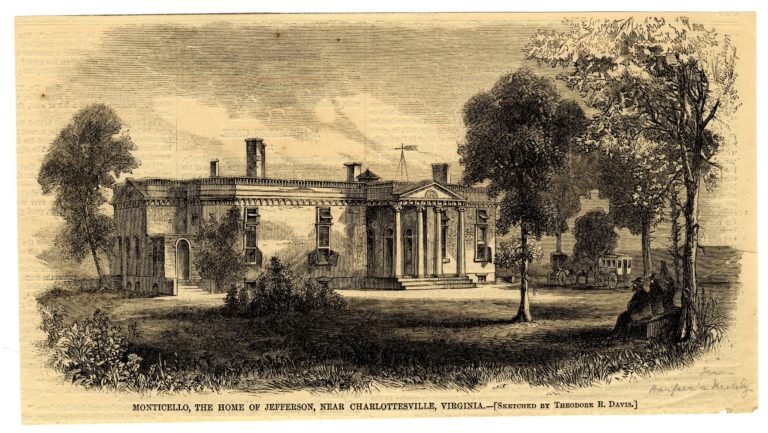

A quiet space with a long oak table running down the middle, the rare manuscript room of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze is lined with drawers full of hand-written index cards, some dating to the early days of the library, which first opened to the public in 1747. I was drawn to the card catalogue on my right, which housed the recent acquisitions collection. A quick perusal of the catalogue confirmed that the collection held nothing filed under Carlo Bellini’s name. Purely out of curiosity, and not wanting to leave the library after so short and futile a search, I took a moment to look up Filippo Mazzei, whose name appeared in much of the correspondence between Jefferson and Bellini. Mazzei came to Virginia in 1773 under the patronage of Grand Duke Leopold of Tuscany, one of the earliest supporters of free trade in Europe. Leopold sent Mazzei to the colonies with the charge of shipping grain back to Tuscany, and once in Virginia Mazzei planned to cultivate a vineyard and produce wine. Perhaps not surprisingly, Mazzei bonded quickly with Jefferson over their shared interest in horticulture and Jefferson’s passion for the Italian culture and language. Mazzei recalled in his memoir that when he met Jefferson in 1773, the Virginian “knew the Italian language very well, but had never heard it spoken.”

I found one card filed under Mazzei’s name. I signed for the document, and was handed a folder containing an original letter written in Italian and accompanied by an archival reference page. Mazzei at the time was living in Pisa and had addressed his letter simply to “Stimatissimo signore, e amico carissimo” (Most esteemed sir, and dearest friend) on September 27, 1812. In the first few lines Mazzei mentions that his letter will be sent with a friend through Paris, though no final destination is cited. There are references to both Monticello and Bellini within the text. Archived in the library as “not signed” and directed to “?” according to the reference sheet, the letter piqued my interest, so I transcribed it in Italian on my laptop. When I returned home from Florence later that summer, the mysterious Mazzei letter remained in a folder labeled “Bellini” on my computer, and quite honestly, I forgot about it. I had no idea to whom it was written, and I figured it was an unsigned draft that had probably never left Italy.

Two years later, with the 240th anniversary of Bellini’s hiring at my alma mater quickly approaching, his ghost continued to haunt me, as did the mystery letter sitting on my laptop. In search of answers, I began studying the extensive republic of letters exchanged between Mazzei and Jefferson archived on the Founders Online website. Right away, I noticed a gap in correspondence between the years 1811 and 1813. At the bottom of Jefferson’s July 9, 1811, letter to Mazzei, a footnote states that Mazzei had endorsed a response as written on September 27, 1812, but that the letter was not recorded in Jefferson’s Summary Journal of Letters and had not been found.

At that moment I knew that I had made an important discovery on that cloudy June day two years earlier in Florence. Mazzei’s detailed response to Jefferson’s 1811 letter had finally made it across the Atlantic and was sitting right there on my laptop in Pennsylvania. But its identification raised more questions than it answered. Had the 1812 letter even made it as far as Paris? If so, how and when did it find its way back to Florence, and why had no other scholars discovered it? Had I unearthed any state secrets? And why wasn’t the letter signed?

I contacted the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, requested a digital copy of the letter, and began the work of tracing the letter from its inception in 1812 to my discovery of it in 2015. As Mazzei had intended, a copy of the 1812 letter was indeed sent from Pisa to Paris amidst the economicand political turmoil that marked the end of Napoleonic rule in Italy, where it eventually landed in the hands of Consul David Bailie Warden, though for some reason was not included in the envelope that Warden later sent to Monticello. The copy that I found in the library is most probably a draft that remained in Pisa. According to their records, the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze acquired this copy of the letter from Lim Antiqua, a manuscript dealer in Lucca, Italy, in 2009. The owner of Lim Antiqua surmises that the letter was likely part of the private archive of Count Luigi Cibrario of Torino, Italian statesman and historian. Lim Antiqua purchased the Cibrario collection in the late 1990s. Interestingly, Count Cibrario was stationed in Paris as the minister of foreign affairs of the Kingdom of Sardinia from 1855-1856 (prior to Italian unification in 1861, the Kingdom of Sardinia included Piedmont, the governing region of much of the peninsula). If this letter was indeed part of the Cibrario collection, he might have acquired it directly from Mazzei’s daughter Elisabetta Mazzei Tozzi Pini, who sold many of her father’s documents following his death. Stashed in a private archive, unsigned and addressed to no one, the letter remained in deep slumber until Bellini’s ghost led me to it in June of

2015. To read the letter in its entirety, click here.