An American Dragoman in Palestine—and in Print

As their tourist party rode on horseback through the hills of the Galilee, young Katharine and Philip peppered their Uncle Allen with questions. Allen loved this kind of back-and-forth—he found nothing more rewarding than regaling the youngsters with stories from his previous adventures in the Holy Land.

The lesson was cut short, though, when a loud noise echoed from the hills. Soon, they found themselves surrounded by “forty or fifty Bedouins, headed by the sheikh.” The party was terrified. Though the young women in the group “neither shrieked nor fainted,” their faces were “blanched with fear.”

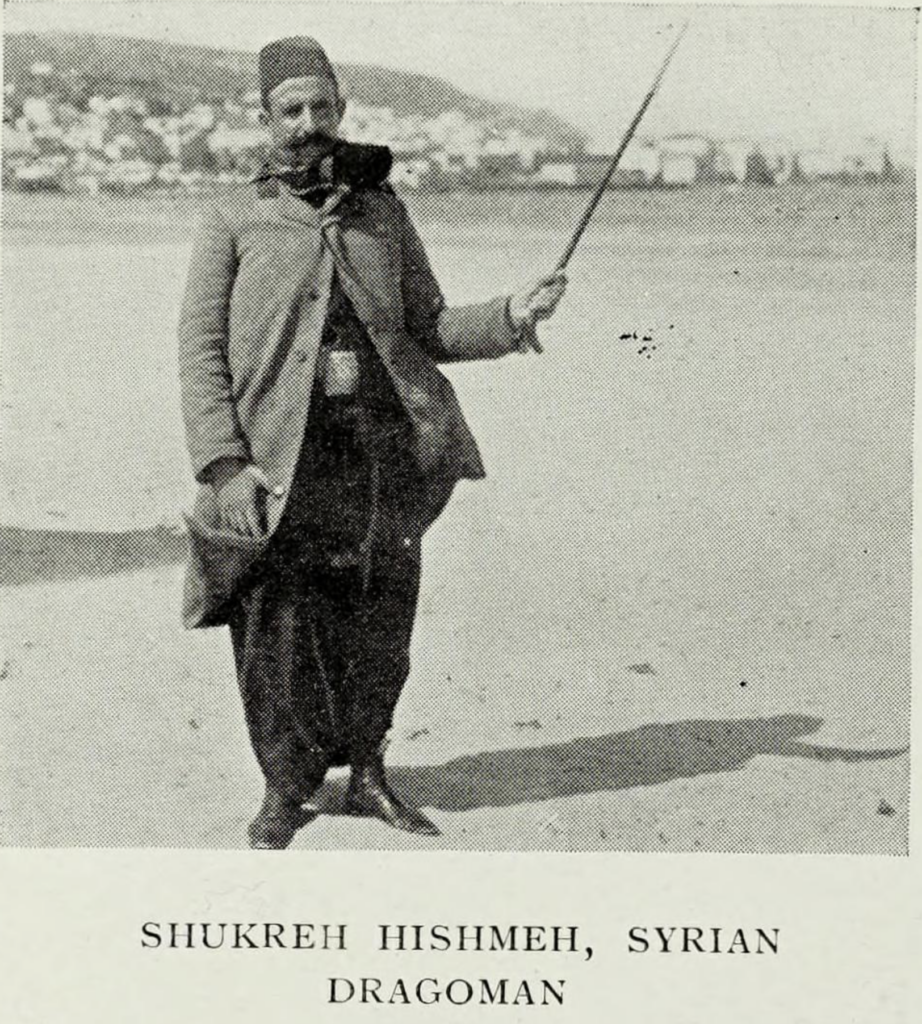

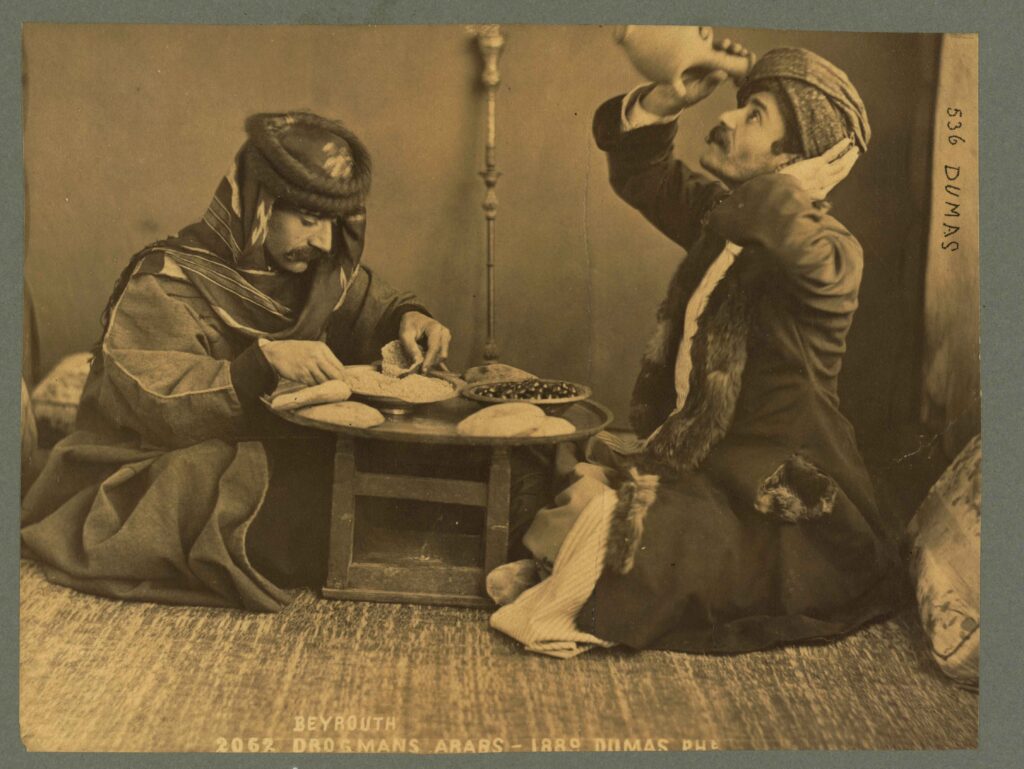

Fortunately, their quick-thinking American dragoman had an idea. Something of a guide, translator, and fixer, the dragoman remembered in that frightful moment that it was the custom “among certain wild tribes to befriend any one in trouble if he reaches the sheik and seizing his belt exclaims: ‘I am your guest.’” As the tribesmen distracted themselves riffling through the tourist party’s possessions, the dragoman seized his chance. He rushed the sheikh, firmly grasped his belt, and exclaimed in Arabic, “These are all your guests.”

According to Allen, the phrase “acted like magic.” The sheikh ordered his men to stand down and drew his sword, announcing that the tourist party was now under his protection. For the remainder of the day, he “guided them for hours through the desert.”

It was a terrifying experience at the time, but Allen had to admit that it “served afterward to add a glow of romance to their tales of travel that could not have been spared.”