An American Flag in Japan: Townsend Harris and the materials of diplomacy, 1857-58

In the archives of the City College of New York, one object catches the eyes of visitors immediately: a large (six-foot by five-foot) faded flag of the United States. The flag was made in 1857, when U.S. flags featured thirty-one stars, arranged in no certain fixed pattern, in the upper left rectangle, or blue canton, that rests on the thirteen red and white stripes of the original federation. Typically, the stripes of the flag were made of imported British wool bunting and the stars and canton might have been of American cotton. This flag, however, was commissioned and sewn in Japan out of silk crepe, copied by “a Japanese Betsy Ross who is as yet unknown, unhonored and unsung,” in the words of Mario Cosenza, the archivist who nearly a century later arranged for the flag to be moved to City College to join the papers of the first U.S. consul general to Japan (fig. 1).

How did this remarkable artifact find its way to City College? What history has it experienced? And what cultural encounters does it continue to stimulate?

The flag is only one of numerous material objects in American and Japanese collections that tell us of the nineteenth-century encounter between liberal and expansionist Americans and the ancien regime of Tokugawa Japan. In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry, first U.S. envoy to Japan, demanded that closed Japan open its markets to U.S. trade. A range of the magnificent visual and material artifacts of that encounter are presented in John Dower and Shigeru Miyagawa’s rich Website Black Ships and Samurai.

Townsend Harris received a commission from President Franklin Pierce to follow up the Perry mission and sojourn in Japan as the first U.S. consul general, arriving in August 1856 (fig. 2). Harris negotiated the Harris treaty of 1858, which furthered the terms for U.S. commercial advantage in Japan. He also established the first official U.S. presence in Japan, in a transformed temple in isolated Shimoda, about one hundred miles from Edo (today Tokyo), the castle town that was then the seat of the shogunal government. After signing the treaty, Harris stubbornly exercised his rights to establish the U.S. consulate general in Edo and moved there for the remainder of his stay, despite violent attacks from hotheaded samurai who opposed the shogunal policy of appeasing barbarian (or foreign) demands.

Townsend Harris (1804-1879) was a self-made businessman whose first career culminated in his entrance into New York City political life. From 1846 to 1848, Harris was the head of New York City’s department of education. In that post he distinguished himself as an advocate for the creation of the Free Academy, one of the first public institutions of higher education in the United States. The Free Academy, or Workingman’s Academy, opened in May 1847 and survives to this day as a public university in New York, part of the City University of New York system. A decade later, Harris, the advocate for accessible and democratic higher education in New York, succeeded in his appeal to the U.S. president to represent the U.S. State Department in various treaty negotiations in Asia. This commission resulted in his post as first consul general in Japan (for his extended biography, see the City College online exhibit The Japan Connection). His career transformation appears to follow a pattern many historians have noted among Americans abroad. As the pattern goes, liberals at home become champions of national expansion abroad—in this case, of course, in the name of “free trade.” But for historians who are today interested in the intertwining of U.S. and Japanese history, it is fortunate that Harris’s stature in New York and at City College has meant that the manuscripts and artifacts from his time in Asia have been preserved.

The U.S. flag that lies in the CCNY archives, then, is a material object that also has a wealth of fascinating written and visual documentation. Harris and his interpreter, Henry Heusken, originally received an American-made flag from the captain of the USS San Jacinto, the naval frigate that brought Harris to Japan in August 1857. On September 4, just before sailing from Japan, members of the San Jacinto crew erected a flagpole over the converted temple in Shimoda that served as Harris’s first home and diplomatic office. Harris’s efforts with the Japanese authorities paid off a year later, when he became the first foreign envoy to travel to Edo for an audience with the shogun.

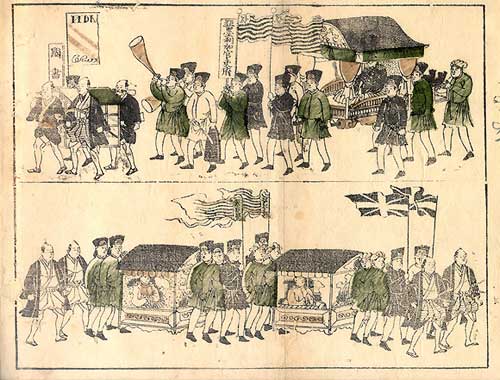

The Harris procession from Shimoda to Edo and his shogunal audience marked yet another of the fascinating pageants of bicultural emblems and ceremony that characterized the Great Power diplomacy across the East Asian world before the twentieth century. And though not as iconic as the Perry expedition, the Harris procession and its American flag were also widely portrayed by Japanese artists (fig. 3).

The above undated Japanese representation of the Harris procession clearly differs from the realism of a pen-and-ink drawing sketched by Henry Heusken in one-point perspective, and not just because the Japanese artist lacked that technique of representation. Here, the size of Harris’s palanquin or norimon, which he had constructed to be much larger and more imposing than typical for a shogun-bound procession, adds a note of historical authenticity. But the initial bearers at the front of the procession are carrying Harris’s credentials in a ceremonial box. An artist’s transformation of the one American flag into two constitutes a didactic embellishment. We can conjecture that the print is a much later representation of the Harris procession, in which the artist encodes not just the later, constructed memory of the occasion but also the newly acquired meaning of the national flag as symbol of U.S. global power.

Harris’s written documentation about the flag is ample. Preparations for the audience began with its manufacture in Japan in silk, as a faithful copy of the San Jacinto flag that was said to have become tattered by the strong winds of the sea town of Shimoda. Harris later wrote in several letters sentiments such as this: “A new flag, made of Japanese crepe, was carried before me. This flag is the first foreign banner that was ever carried through the great city [Edo], and I mean to preserve it as a precious relic.”

Townsend Harris devoted many pages in his journal to the procession to Edo, which averaged about fifteen miles a day and comprised over 350 persons. At the procession’s head, Japanese samurai officials cried out in rhythm orders for the surrounding populations to “sit down” (in Harris’s words) in respect as the procession passed. “Next came the American flag guarded by two of my guards,” Harris wrote. “Then I came on horseback with six guards, next my norimon with its twelve bearers and their headmen; bearers of my shoes, etc., etc.” As would have been the case at the time, the procession bearers were changed every five miles as others stepped in to fulfill labor requirements imposed by the Tokugawa order.

Harris details the gown of his “standard bearer” and remarks on the insignia that was emblazoned on the dark blue coats of his norimon bearers, as “the arms of the United States on the back” (fig. 4). Indeed, many of his personal effects were covered in cloth bearing these “arms,” an emblem tantamount to the Japanese crest that a daimyo or other notable would display to mark his status as lord. While the American banner, flying from its pole, may not have been read by contemporary Japanese as a national emblem, they certainly could read representations of family or aristocratic crests as symbols of power. Thus, the procession was well equipped to convey the stature and gravity the United States wished to communicate. The hybridity of Japanese and American, or Western, symbols in the procession echoes the many other trappings of diplomatic and colonial ceremony employed across the world in an era of imperial expansion.

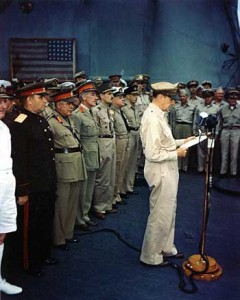

Many books have been written about the history of the American flag. In the history of U.S.-Japan relations, however, the U.S. flag on Japanese soil has had an exceptional resonance. At the formal surrender of Japan to the United States in 1945, aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, the United States authorities displayed the same flag Perry had flown over his gunboats in 1853 (fig. 5). Historian John Dower has noted that this American gesture of power constituted a “reprimand” to the Japanese for their wartime defiance. We can only hope that the Harris flag retains a less controversial, less fraught symbolism. After all, Minister Townsend Harris, while voicing his sentiment to preserve this flag as a “precious relic,” nevertheless left it to civic institutions; the archives of City College acquired it in the 1950s from Townsend Harris High School in New York. For some Japanese, anyway, it seems to be remembered with warmth and nostalgia for the period of Japan’s “opening” to the West.

Since the late 1980s, City College has welcomed a revival of Japanese interest in the Townsend Harris archive, which has included an annual visit from a delegation of the city council of Shimoda. For the coming 150th anniversary of the signing of the Harris treaty next year, Japanese museums and civic groups are preparing festivities and exhibits, and several of the treaty documents in the collection will be on display in Japan. The flag, however, faded and fragile, will remain in the archives, where it will continue to stimulate bicultural encounters for a long time to come.

Further Reading:

I wish to thank Professor Sydney van Nort, archivist of the City College of New York Library, for invaluable help with this essay and for her further research into the life of Townsend Harris as shown in the CCNY Website on Harris, The Japan Connection.

Primary sources for Harris in Japan include: The Complete Journal of Townsend Harris, First American Consul and Minister to Japan,introduction and notes by Mario Cosenza, 2nd ed. (Rutland, Vt., and Tokyo, 1959); Henry Heusken, Japan Journal, 1855-1861, translated and edited by Jeannette C. van der Corput and Robert A. Wilson (New Brunswick, N.J., 1964); the Archives of the City College of New York, Townsend Harris Collection. A recent study of U.S.-Japan diplomacy that reexamines Harris’s diplomacy is Michael Auslin, Negotiating with Imperialism: The Unequal Treaties and the Culture of Japanese Diplomacy (Cambridge, Mass., 2004).

The general territory of this essay has been well covered by historian John Dower. Dower and Miyagawa’s Black Ships and Samurai Website is an exemplary virtual exhibition of material and visual materials of the nineteenth-century encounter of Japanese with Commodore Perry. The whole project is entitled Visualizing Cultures and is part of the MIT OpenCourseWare project; not to be missed within it is John Dower’s excellent video tour of the history and the visual materials in his exhibit. Dower is also the author of Elements of Japanese Design: Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism, 2nd ed. (New York, 1990).

Other scholars have written of Japanese depictions of foreigners, notably Ronald Toby, who recently curated an exhibit at the Art Institute of Chicago and wrote “Foreign Faces in Japanese Prints” in the online journal Asian Art. Finally, Marc Leepson, Flag: An American Biography (New York, 2005) and William Rea Furlong and Byron McCandless, So Proudly We Hail: The History of the United States Flag (Washington, D.C., 1981) were helpful to contextualize this flag.

This article originally appeared in issue 8.1 (October, 2007).

Barbara Brooks is associate professor of history and Asian studies at City College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. She has published on Japanese diplomacy in China and on cultures of Japanese colonialism in its Asian empire.