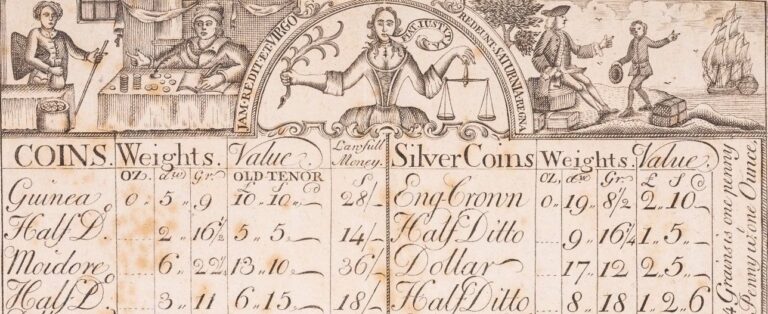

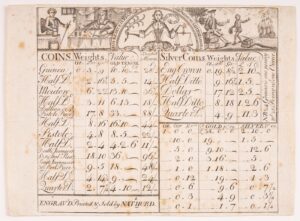

When the sheriff found the coins at the forge in the North Carolina swamp, he noted they were “so badly done as not to be easily imposed upon any Body; which may be owing to the timely Discovery of the Plot, which prevented their finishing them in the Manner they intended.” The finishing process he refers to included achieving a realistic silver or gold coloring on the coin’s surface that would have been Johnson’s job as the chemist. After the metallic disc was removed from its mold, it had to be brought to the color of a silver coin even though in actuality it was not entirely silver. To do so, the coiner would first apply vitriol (sulfuric acid) or aqua fortis (nitric acid) that dissolved whatever silver was in the new coin (often filed off another coin) and forced it to the surface. Mineral acids like vitriol and aqua fortis were used broadly to dissolve metals in various manufacturing processes and make spirituous tinctures for stomach ailments, for example. Next, tartar was added to the silver and acid mixture to form a paste that could be rubbed into the coin’s surface to give it the color of a true peso or pistareen. Forms of tartar were commonly used to make the pastes and mashes that were rolled into pills using similar hand motions to the process of coloring a coin.

Any number of physical characteristics related to the finishing process could suggest that a coin was bogus, besides being found near a forge set up in a swamp, of course. The sheriff who uncovered Johnson’s cache noted that the coins appeared to be of correct size but were “wanting in Colour.” Perhaps Johnson’s coins showed some of the brass underneath the silver coating like the counterfeit pesos mentioned in the October 6, 1760, issue of the Boston Gazette that “if rubbed they will look brassy.” Other bogus coins appeared coppery or bluish rather than silvery white, the surface providing physical clues to their internal composition akin to the role of the skin in medical diagnosis as a screen showing what occurred underneath. Or maybe they still felt wet or smelled of the tartar paste like several counterfeits reported from New Hampshire in 1774 that emitted a chemical odor giving away their recent production. People bit their coins to determine if they seemed too soft (indicating lead content) or rang them against a hard surface to evaluate the metal’s resonance against how they thought silver should sound.

Without standardized testing, except in certain circumstances, identifying coins remained a form of artifice requiring experience and embodied knowledge of using the senses to evaluate a coin’s characteristics. The references evoked to determine genuine appearance, texture, smell, sound, and taste remained flexible and quite local, such as the example of the blue hue of the local slate used in grave markers. Combined with the usefulness of circulating coin, whether suspicious or not, this meant that counterfeiters often avoided punishment due to acquittal or escape, though many others across the Anglo-Atlantic world suffered physical injuries and death for their actions, including Daniel Johnson.

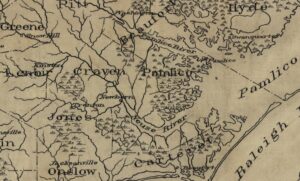

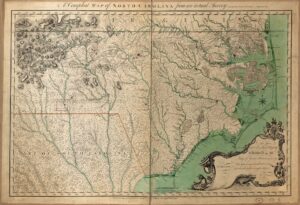

News about the coiners caught outside New Bern spread quickly along the Atlantic coast during the autumn of 1752. There remains no record of what defense they offered, though alleged coiners in London pointed to their trades in related fields, including as apothecaries and belt buckle makers, as reasons for possessing suspicious equipment or materials. Still others claimed the difficulties of telling good coin from bad as the reason for their working with coins to learn the distinctions. Whatever their assertions, North Carolina’s General Court sentenced William Jillet and Daniel Johnson to death for treason after one of their group, Patrick Moore, the tailor, turned evidence against them to avoid a similar fate. Despite several attempts to escape the jail in New Bern, which quite a few seem to have been able to do, Johnson and Jillet arrived at gallows erected outside New Bern in October 1752 where they both died by hanging according to accounts.

The case of Johnson, Moore, and Jillet at once reflects the patchwork enforcement of imperial monetary law in British North America and the conditions of scarcity underpinning it, but their failure underscores the complexity of the ideas and practices involved in making veracious coins at the time. Success involved craft skill, chemical knowledge, sufficient materials, a suitable place to work, and quite a bit of luck—not all of which the men ended up having. The remaining traces of their story help us reframe currency as a chemical art in addition to a political project and to think about it in terms of work at the margins of the law at a time when concerns about money occupied the minds of so many across the Atlantic world. By pairing the study of medicine and money, the labor of artisans, including those experienced in the vernacular chemical arts, can be made a bigger part of histories of knowledge and value production, especially in spaces or by people usually invisible in narratives of monetary development or scientific innovation. The embodied components of detection, likewise, encourage us to consider the role subjective qualities played in practices of enforcement that have been made to appear more objective or standardized over time.

Further Reading

Newspaper accounts of the New Bern coiners can be found in the Virginia Gazette, October 12, 1752, and the Boston Post-Boy, December 5, 1752, as well as in other regional newspapers from around that time. Kenneth Scott, Counterfeiting in Colonial America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1957) and Philip Mossman, From Crime to Punishment (New York: American Numismatic Society, 2013) offer detailed background on the histories of counterfeiting and coining in British North America, while articles including Carl Wennerlind, “The Death Penalty as Monetary Policy: The Practice and Punishment of Monetary Crime, 1690-1830,” History of Political Economy 36 (no. 1, 2004) and Katherine Smoak, “The Weight of Necessity: Counterfeit Coins in the British Atlantic World, Circa 1760-1800,” William and Mary Quarterly 74 (no. 3, 2017) give nuanced analyses of the enforcement, hierarchies, and variability of money across the British Atlantic world. On chemistry in the Americas, see Annals of Science 77 (no. 2, 2020); and for the connection between alchemy and medicine, see William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe, Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate of Helmontian Chymistry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). The move toward uniting the head and the hands in studies of science is exemplified by Pamela H. Smith, The Body of the Artisan: Art and Experience in the Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004) and Lissa Roberts, Simon Schaffer, and Peter Dear, eds., The Mindful Hand: Inquiry and Invention from the late Renaissance to Early Industrialization (Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2007). The New Dispensatory (London: 1753) offers examples of the practical overlap between making medicines and making coins, while the broader context of merchants of medicines in this period can be found in my book, Zachary Dorner, Merchants of Medicines: The Commerce and Coercion of Health in Britain’s Long Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020). Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp has been the subject of renewed interested over the past decade, including Sylviane A. Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons (New York: New York University Press, 2014) and Daniel O. Sayers, A Desolate Place for Defiant People: The Archaeology of Maroons, Indigenous Americans, and Enslaved Laborers in the Great Dismal Swamp (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014).

This article originally appeared in August 2022.

Zachary Dorner is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Maryland, College Park. His work blending histories of health and commerce has appeared in the William and Mary Quarterly, Journal of British Studies, and Boston Review; while his first book, Merchants of Medicines: The Commerce and Coercion of Health in Britain’s Long Eighteenth Century, was published by the University of Chicago Press in 2020.