Paper Money Gets Personal

Reading credit and character in early America

“Money talks,” we’re often told, because it can convey far more meaning than mere words. But in eighteenth-century America, paper money could literally talk. When I undertook years ago to write a book on economics and letters in early America, I expected that paper money would figure thematically in the era’s essays, broadsides, poetry, novels, and drama. I was surprised to discover, however, that paper money was often a literary character with much to say: a tale-telling traveler, a shameless liar, a martyr offering up his dying words.

As literary devices, these talking personae produce mixed results. Sometimes they are clever, and just as often they are contrived and heavy handed. But, putting aside the question of their literary merit, I have often wondered why writers were inclined to make paper money a fictional character in the first place. Why give a piece of money an identity and a platform from which to speak? What can this peculiar literary maneuver tell us about paper money as a social phenomenon?

By turning paper money into the character Paper Money, writers could draw a compelling analogy between personal and national credibility. In contrast to coins or “hard money,” which obtained currency through the metal’s market value, paper money relied extensively on the faith of buyers and sellers in the government’s word. These “bills of credit,” which constituted a debt on the government’s part, were essentially IOUs issued by legislative proclamation at times when there were not enough metal coins in the public coffers to cover expenses. Like an individual seeking credit, then, the government needed to offer proof of its integrity to make these monetary promises convincing. As one Massachusetts politician proclaimed in 1787, states “become respectable on the same principles by which the character of individuals is maintained.” This analogy was serviceable to both critics and supporters of paper money.

In the hands of critics, the persona of Paper Money becomes, not surprisingly, a charlatan. He speaks words the reader can never entirely trust, and he dramatizes the risks inherent in all forms of money that rely on verbal promises rather than tangible forms of wealth. When Benjamin Franklin penned an essay publicly supporting a 1775 issue of Continental dollars, for example, critics responded with a series of satiric pieces depicting Paper Money as a social-climbing masquerader. In these satires, man and money mislead readers in similar ways. Franklin is the humbug who fashions himself as learned by speaking a smattering of Latin. Paper Money, who not coincidentally bears Latin mottoes, is also an imposter of sorts: he proclaims a value that cannot be backed up by collateral.

such writings, the persona of Hard Money often provides a foil to his paper counterpart. Hard Money insists that the accurate assessment of personal character and monetary value alike is the prerogative of an elite class of “reading men” who are “able to conceive that first appearances are oftentimes deceitful, and that all is not gold that glitters.” He is a man of substance, honorable birth, and fluency in all languages (metal’s widespread acceptability making it universally conversant). Paper Money, by contrast, is the obscure and untrustworthy child of a Philadelphia printer and given to “affecting an importance, as if he had been equal to the solid coin.” In the most obvious sense, he is the brainchild of Franklin, a retired printer, and the product of the Philadelphia printing house Hall and Sellers. But Paper Money’s parentage also aligns credit use with the tradesman. In the class-conscious satire of these essays, “substance” refers both to the tangible material of metal coins and to the status and capital of landowners.

This character’s lineage also implicates paper credit in a larger print culture that is susceptible to corruption. By making possible mass-produced and standardized texts, printing lent an aura of legitimacy to paper money, promissory notes, newspapers, tracts, broadsides, and other media. But a man might also hide behind print and assume a false identity in a newspaper or broadside that he could not so easily assume in a face-to-face encounter. And a printed bill might seem official and yet still make promises it could not keep. Worse yet, it might be a fake, for the more standardized and generally reproducible a bill was, the more easily it might be counterfeited.

A decade later, a series of speeches by Paper Money in the Worcester Magazine dramatically illustrated these risks for readers. In the September 1786 issue, the much maligned Paper Money defends himself by reminding readers that he was instrumental in funding the Revolutionary War. But, in the November issue, Paper Money rescinds this claim and admits to having been a “tool of knavery, dishonesty, fraud, and injustice.” In the January 1787 issue, however, Paper Money announces that the November speech was submitted by an “imposter.” He repeals the repeal and stands by what he said in the first speech. Paper Money has been impersonated in print, highlighting just how easily a paper bill might be counterfeited.

The November masquerade is somewhat ironic, given that it aims to castigate dishonesty, but its creator would likely have drawn a distinction between the impersonation of a fictional device and that of a living individual. To the writer of the November speech, the real frauds are paper money and its supporters. Such a critic would perceive little difference between these supporters and a man like Stephen Burroughs, the notorious eighteenth-century confidence man whose dreams of easy wealth drove him to counterfeit coins. One might argue that Burroughs distorted the initial logic behind credit by creating unauthorized money that constituted theft rather than borrowing. But, in the minds of its opponents, even legitimate paper money was a counterfeit like the one Burroughs admired—a pretense of material value that is not present or tangible.

As we might expect, paper money cuts a very different figure in the literary efforts of its supporters. Advocates of paper money did not deny its risks, but they also saw it as a resource that could expand the money supply and, in so doing, facilitate exchange and stimulate enterprise. In their writings, the character Paper Money is still a man lacking in “substance,” but his insubstantiality takes on a decidedly positive spin.

Paper Money cannot match Hard Money in material value, but, as a printed text, he is kin to the progeny of great authors: “If a Printing-office was the place of my nativity,” he writes, “so has it been of the noblest productions that ever blessed or adorned the world.” He boasts elsewhere, “I am by the mother’s side of the family of Paper; a family that has been of more service to the commonwealth of letters than all of the name of Hard-Money that ever have existed.” Paper Money acts without the backing of material wealth and so is a testament to the power of legal language. In a political climate that has enshrined documents like the Constitution and Declaration of Independence, his lineage is something to be celebrated.

This version of Paper Money certainly lacks wealth and status, but for this reason, it also fits nicely into a story of American opportunity. A case in point is “The Adventures of a Continental Dollar,” a serial narrative of which two installments appeared in The United States Magazine before the periodical folded in December 1779. In this tale, Paper Money admits he has neither the capital nor prestige that Hard Money enjoys, but he insists nevertheless that readers not overlook his potential. Far from an “upstart coxcomb,” as his detractors have dubbed him, he is an “enterprising genius.” This Paper Money is the son not of the printer but of Liberty. He is a risk-taker, born “in the centre of the vast continent of North-America” where “boundless and unexplored regions” are fit for such “free and uncountrouled souls” as his.

The spaciousness of the American continent links paper money to New World exploration and immigration. Readers of North American settlement narratives and promotional tracts know how consistently they embrace the language of potential and opportunity. It is worth emphasizing, however, how often such narratives make debt and credit use the first step to realizing that potential and acting on that opportunity. In William Bradford’s archetypal account of the Plymouth colony, the Puritans must brave rough waters and a hostile wilderness but also borrow heavily from London merchants in order to finance their journey. In the next century, J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur’s “What is an American?” would proclaim that the model American immigrant uses borrowing to exceed the limitations of his capital and convert dreams to reality.

In keeping with this equation of indebtedness with liberation, Paper Money sometimes figures as a martyr who has died bringing about individual and collective autonomy. A broadside by Joseph Green, published as the colony of Massachusetts began retiring its bills of credit in 1750, features the “Dying Speech” of a paper bill who is soon to be permanently removed from circulation and relegated to the flames. Although the speaker admits that his value was inflated and he was manipulated to serve “the worst of Mortals,” he also reminds his readers that he helped the poor man in distress and provided funding to fight colonial wars and build communities. Similarly, Green’s 1781 ballad broadside, “A Mournful Lamentation On the untimely Death of Paper Money,” eulogizes paper money as a martyr who died for American freedom:

He rais’d and paid our Armies brave.

To guard our threaten’d State;

Whose val’rous Deeds their Country save,

And num’rous Foes defeat.

Sung to the traditional English tune of “Chevy Chase,” this ballad celebrates a recently retired issue of Continental money for its role in national independence.

Although Green laments the death of Paper Money, other writers considered his death essential to American success. For example, M’Fingal, John Trumbull’s 1782 epic poem of the Revolution, proclaims that the Continental dollar must die in order to do its duty. Marching to his grave in the vision of the fourth canto, Paper Money appears limping on crutches, draped in tattered robes, and bearing a breastplate that reads, “The faith of all th’ United States.” Although an admirable patriot, he must “perish in his country’s cause,” for only with the retirement of its debt can the nation’s honor be maintained. Trumbull anticipates the day when the Continental bill will lie buried in eternal peace, and he does not envision a permanent national paper money.

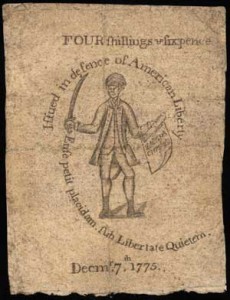

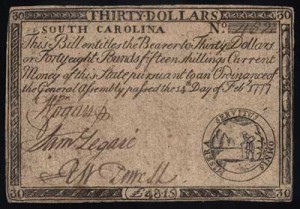

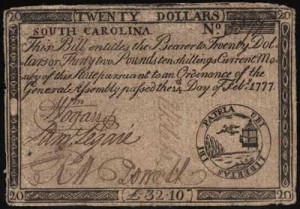

That Paper Money, as living hero and martyr, was often a national liberator was amply reinforced by the rhetoric of bills themselves. The 1775 “Sword in Hand” bill (fig.1), engraved by Paul Revere and issued by Massachusetts at the start of military conflict with England, features a soldier holding the Magna Charta and the words, “Issued in defence of American Liberty.” In another issue the following year, the soldier’s Magna Charta is replaced by the Declaration of Independence. Two 1777 South Carolina bills also celebrate freedom (figs. 2 and 3). One announces Servitus Omnis Misera, or, “All Forms of Slavery Are Wretched” (with obvious irony, given the prevalence of chattel slavery in the region). A second bill features a bird fleeing a cage and the motto Ubi Libertas Ibi Patria, or, “Where There Is Liberty, There is Homeland.”

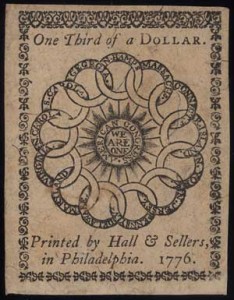

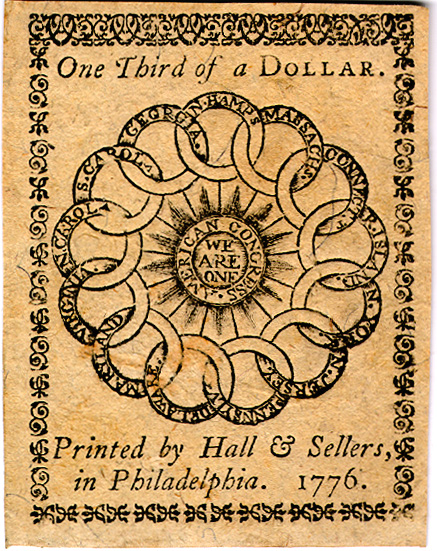

Even in his most flattering portraits, the figure of Paper Money must compensate for his deficiencies. Paper money is a “necessity” in the specific eighteenth-century sense of the term: prompted by pressing economic constraints and a paucity of monetary options. But that should not obscure the extent to which many writers perceived the instability of credit schemes and their reliance on popular opinion as a valuable communal resource. If commercial credit was the trust one placed in a person’s ability and willingness to meet financial obligations, public credit was the trust one placed in a government’s ability and willingness to do so. What initiated public credit was a debt, and hence a limitation, on the government’s part, but public credit was nevertheless an expression of confidence in the new nation’s viability. For this reason, the rhetoric of Continental dollars typically tried to foster this confidence by implicitly linking financial venture to communal commitment. In a one-third dollar bill (fig.4), for example, the motto, “We are One,” is accompanied by the image of thirteen interlocking rings, suggesting that the fates of all states are intertwined by the political and economic venture of rebellion.

If we return to “The Adventures of a Continental Dollar,” it is clear that Paper Money necessarily relies more than Hard Money on faith and that such faith figures as a valuable expression of public commitment. Speaking of men who publicly endorsed him shortly after his birth in America, Paper Money recalls, “They were the first men that owned me, and stood up for me in the infancy of my affairs, entered into a league with me, and stood firm to it in despite of all the hazards of an uncertain fortune.” Here Paper Money acknowledges the hazards he has brought to the new nation but also insists these hazards exact a measure of commitment. In this and other instances, the speaking bill describes financial faith but also, in so doing, attempts to solicit faith from the reader as well. When Paper Money speaks, in other words, he has in mind a reader who may well be in a position to extend his or her credit to the nation’s money.

As twenty-first-century readers, we cannot experience the persona of Paper Money just as our eighteenth-century counterparts did. These bills are not our own but the relics of a past era. Monetary experience has changed dramatically, and we have no expectations today that our greenbacks will ever be redeemed for metal coins. We might be optimistic or pessimistic about the strength of the dollar or of our economy in general, but we do not think of a paper bill as a voucher awaiting redemption. Eighteenth-century paper money talked by using legal language to proclaim a value not backed by collateral, and buyers and sellers were not always sure how to read these promises. At times a trickster, at times an underdog beseeching support, Paper Money took to talking as a response to Americans’ mixture of skepticism and faith.

Further Reading:

For general histories of early American money, see Eric P. Newman’s The Early Paper Money of America (Iola, Wisc., 1990) and William G. Anderson’s The Price of Liberty: The Public Debt of the American Revolution (Charlottesville, Va., 1983). Newman’s book includes facsimiles of many bills, and more images of bills can be found on the Website Colonial Currency, a project of the Robert H. Gore, Jr. Numismatic Endowment at the University of Notre Dame. For a sustained analysis of paper money and early American writing, see Jennifer J. Baker’s Securing the Commonwealth: Debt, Speculation, and Writing in the Making of Early America (Baltimore, 2005). For examples of Paper Money as a literary protagonist, see Joseph Green, “The Dying Speech of Old Tenor” (Boston, 1750) and “A Mournful Lamentation On the untimely Death of Paper Money” (Wilmington, Del., 1781); “The Adventures of a Continental Dollar,” United States Magazine (June 1779): 264-268 and (September 1779): 385-387; “Paper Money once more speaketh for itself!” Worcester Magazine 2:31 (November 1, 1786): 372-373; “Paper Money once more speaketh for itself!” Worcester Magazine 2:40 (January 1, 1787): 482-484; “Paper Money, raised from the dead, speaketh for itself!” Worcester Magazine 1:25 (September 15, 1786): 294; “Reply of Continental Currency to the Representation and Remonstrance of Hard Money” United States Magazine (February 1779): 72-81; “The Representation of Remonstrance of Hard Money,” United States Magazine (January 1779): 28-31.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.3 (April, 2006).

Jennifer J. Baker is assistant professor of English at Yale and the author of Securing the Commonwealth: Debt, Speculation, and Writing in the Making of Early America (Baltimore, 2005). She is currently writing a book on antebellum American literature and the Victorian life sciences.