Beards, Bachelors, and Brides: The Surprisingly Spicy Politics of the Presidential Election of 1856

Old Bachelors are low in rate,

Few days, few days;

They’d never populate a state:

We’re going home.

The white house party’s must not drag,

Few days, few days;

And what could BUCKS be but a STAG:

We’re goin’ home.

—“There is the White House Yonder, or the Frémont Campaign Song” (1856)

The presidential election of 2016 has already been one for the history books. Extreme campaign promises, heated debates, and ad hominem attacks of all kinds have been its watchwords. And to be expected in our own time, where men and women compete equally for the nation’s top political spot, issues of sex and gender have frequently come to the fore. From Donald Trump’s outright sexist remarks about the physical appearance of female candidates, to the more subtly misogynist and insidious questioning of Hillary Clinton’s ability to lead, to the emergence of “Bernie Bros” and their outspoken feminist critics, this election season has proven nothing, if not that the battle of the sexes is still alive and well in the twenty-first century.

In the face of the frenzied fracas that has become the 2016 presidential election, we naturally look to the past to make sense of it all. After all, questions, or more properly allegations, aspersions, and downright attacks of a gendered and sexual nature have long fashioned the rhetoric of presidential elections. In 1804, for example, the Federalists accused Thomas Jefferson of an interracial sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings (proven correct, as turns it out), while in 1800 the Democratic-Republicans had attacked John Adams as possessing a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.” Those were fighting words in fighting days—the infamous Burr-Hamilton duel was four years away—but neither side suffered much the worse for their indiscretions. Since then, the personal lives of presidential candidates have been fair game for the public’s scrutiny and scorn alike.

Yet, across the pantheon of presidential elections in early America, few have stressed the themes of sex and gender so spicily as the heated contest of 1856. It was a year of many firsts. With the Whig Party more or less in the grave, the new Republican Party chose the bearded John C. Frémont of California as a virile representation of the new party’s antislavery convictions. Equally important to the Frémont campaign was his beautiful wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, the daughter of the legendary senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. Meanwhile, the Democracy—the preferred name for the grand old party of Jefferson and Jackson—ran the aged bachelor James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. The first such presidential candidate never to have taken a vow of marriage, at sixty-five, he was also the oldest man to seek the office since George Washington.

A beard, a bachelor, and a bride. The combination could provide the tagline to a modern sitcom. But the presidential election of 1856 was no laughing matter, as an unprecedented sectional feeling of tumult pervaded the nation. In May 1856, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina had caned Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts on the floor of the U.S. Senate. Likewise, violent encounters between proslavery and antislavery forces racked the Kansas territory, so much so that the place had obtained a new moniker: “Bleeding Kansas.” In addition, a nativist coalition opposed to immigrants and Catholics offered a viable third-party challenge in the form of the widower and ex-president Millard Fillmore of New York (under the banner of the American Party or Know Nothings, as they were commonly called). Finally, social issues were insistently creeping like never before into the American consciousness, with cries of abolition, prohibition, and women’s suffrage being shouted in louder voices than ever before. In such an environment, for one man to be right, another necessarily had to be wrong.

With the political stakes that much higher in 1856, the nation was actually asking a much larger, gendered question: what makes for a “real man”? In the tumultuous political climate of 1856, the electorate of mostly white men could reach no easy consensus. Competing views of manhood, usefully delineated by the historian Amy Greenberg as “martial” and “restrained,” divided the nation along sectional lines. The more industrialized and urbanized North valued “restrained” forms of manhood, while the more agrarian, slave-holding South lionized “martial” manhood. These gendered differences routinely filtered into the political questions of the day. Conservatives derided pro-feminist proponents of women’s suffrage as “Aunt Nancy” men; abolitionists lambasted the destruction of black motherhood in the slave-holding South as morally evil; and filibusterers in Central America justified their conquest on racialized expressions of superior manhood. To a large degree, differences over gender had become as contentious as the traditional divisions engendered by sectional or party politics.

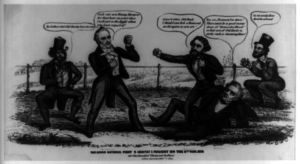

More than in previous presidential elections, political cartoons transformed visually the partisan battles of Democrats, Republicans, and Know Nothings into personal battles among fighting men. Usually distributed as standalone prints, the stunning visual imagery crystalized the meaning of political battles into pictorial, and very often gendered, terms. In “The Grand National Fight 2 Against 1 Fought on the 6th of Nov. 1856 for One Hundred Thousand Dollars,” Buchanan is depicted as a dignified but strong man, fully capable of knocking down his opponent Frémont in a match of fisticuffs (fig. 1). The caption above Buchanan reads “Look out now Young Mariposa for that hair on your face I will put in the ‘Right’ when you least expect it!” The allusion to Mariposa, a knock at the poor performance of the California State Militia in the so-called Mariposa War of 1850-1851, was meant as an attack on Frémont’s adopted state of California and implicitly on his manhood as well.

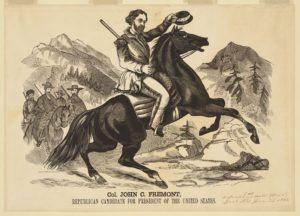

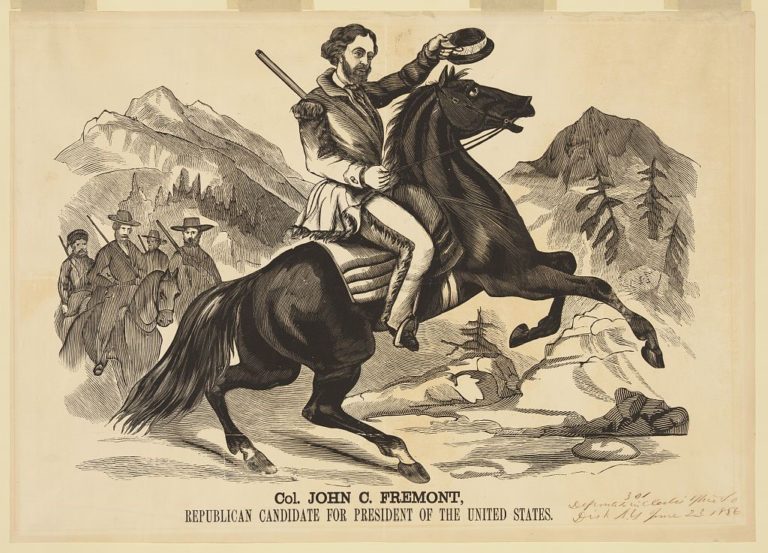

The reference in the political cartoon to Frémont’s full beard also hints how facial hair was a point of growing emphasis in the battle for manhood. As opposed to the fashionable look of trimmed facial hair sported by young men in cities, Frémont’s beard, full and flowing, displayed a more overtly macho look that recalled his many years of service as a soldier. His was a decidedly martial beard, as evidenced by one cartoon that pictures the former soldier mounted on horseback, his cap waving ostentatiously in the air (fig. 2). In contrast, the whiskerless Buchanan claimed the legacy of Andrew Jackson (who was also beardless), not only in his Unionist policies, but also in his invocations of a lack of facial hair as a marker of restrained manhood. The clean shave had long been the sign of gentility among the older generation, and the conservative and fastidious Buchanan followed suit. In 1856, voters would decide more than just which party represented their views. They would also select the man who best embodied their idealized version of manliness.

Given the Democratic Party’s association with continental expansion, empire, and general aggressive action abroad, there is a decided irony in the choice of the bachelor Buchanan as its candidate. For one thing, Buchanan lacked military experience. As compared to most of the previous candidates of the Democracy, such as Andrew Jackson, James Polk, Lewis Cass, and Franklin Pierce, Buchanan had never soldiered professionally. In this sense, he hearkened back to Martin Van Buren (the only Democratic president before the Civil War not to serve in the military), and who like Buchanan had been secretary of state to a previous president (Van Buren under Jackson, and Buchanan under Polk). For another, at age sixty-five, Old Buck (as his most common nickname implies) stood as a symbol more for the Democratic past than the Democratic future.

In contrast to the bachelor Buchanan and the widower Fillmore, the Republican Party standard-bearer boasted a beautiful bride in Jessie Benton Frémont. By 1856, Senator Benton’s daughter was already known nationally. In the lead-up to the Republican national convention, she promoted her husband’s candidacy among an extended network of political connections, most especially the influential former Jacksonian editor Francis Preston Blair. But the peculiar circumstances of the Frémonts’ marriage exposed the Republican frontrunner to a political liability; for, although Frémont was an Episcopalian, the couple had married in the Catholic Church in 1841. The Know Nothings and the Democrats seized on this fact and attempted to portray the candidate as enthralled to the Catholic power. So, too, might an asset become a liability, when Thomas Hart Benton threw his support to Buchanan over his own son-in-law. “I am above family and above self when the good of the Union is concerned,” Benton declared.

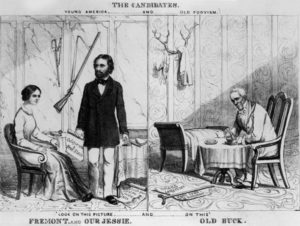

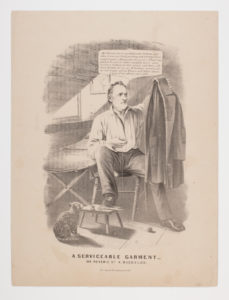

Indeed, the campaign propaganda on all sides made much of marital status (or the lack thereof). Especially noteworthy was the comparison of the domestic ideal of the marriage of John and Jessie Frémont with the pathetic state of Buchanan’s bachelorhood. For Republicans, the beautiful Jessie Benton Frémont presented a political asset to be publicly touted. In one cartoon, “The Candidates,” the two camps “Young America” and “Old Fogyism” correspond to their candidates, “Frémont and Our Jessie” and “Old Buck,” respectively. The dichotomy could not be starker: the Frémonts enjoying the pleasures of domestic life versus Buchanan suffering alone in bachelor’s quarters (fig. 3). In another cartoon, “A Serviceable Garment—or Reverie of a Bachelor,” the artist depicts Buchanan as a poor bachelor whose long history of public service seems more a liability than an asset (fig. 4).

The contrast between the marital bliss of the Frémonts and the sad state of Buchanan’s bachelorhood also received special treatment in campaign songs and at political rallies. Devout Republicans hummed along to such tunes as “We’ll Give ‘Em Jessie,” “Huzza, for the Railroad,” and “Frémont and Freedom.” Of the trio, the first song cleverly inverts the expected sequence of events, placing Jessie above her husband as the main attraction to potential voters. Yet, the themes of manhood did not lurk far behind. “In every word, in every deed / Such manliness appears, / Frémont’s the man to lead us on / To beat the Buchaneers.”

In the beautiful Jessie and the handsome John, the Republicans offered a virile, coupled alternative to Buchanan’s sterile, singular bachelorhood. Republican newspaper editors regularly made the comparison. Typical is a line from “A Northern Republican” in William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator of October 1856: “The Democrats have no feminine element in their two-legged, walking platform; no Jessie to hurrah for; no Jessie to vitalize their manhood and kindle their enthusiasm! Theirs is a bachelor party, and it will be a bachelor Administration if they get it.” At Republican rallies, the party touted its candidate’s marital strengths. “No Bachelor for JESSIE: Free Hearts and Free Homes,” Republican Horace Greely’s New-York Tribune reported of one rally upstate. Through her marriage, her beauty, and her behind-the-scenes maneuvering, Jessie Benton Frémont helped the Republicans to expand their message beyond free soil, free labor, and free men, to include the equally critical themes of free hearts and free homes. And given that few images circulated of Jessie, songs and rallying cries were that much more important in the popular imagination.

With their invocations of “We’ll Give ‘Em Jessie,” the Republicans enjoyed a decided edge in the musical battle for the people’s hearts. For their part, the Democratic Party actually defended their bachelor candidate, though in the medium of print rather than song or cartoon. The party’s authorized campaign biography, written by the New York editor and slavery apologist Rushmore G. Horton, did not back away from its candidate’s bachelor status. Instead, Horton embraced Old Buck as an exemplar of restrained manhood and Democratic principles: “[Buchanan] is now about sixty-five years of age and has never married,” he wrote. “His family consists of himself and niece, whose … knowledge and sense, derived from books, study and reflection, peculiarly qualify her to grace and cheer the fireside of the Sage of Wheatland.”

Other Democratic supporters went further still. At the Democratic nominating convention in Cincinnati, the Buchanan supporter and future attorney general Jeremiah Black declared: “[A]s soon as James Buchanan was old enough to marry, he became wedded to the Constitution of his country, and the laws of Pennsylvania do not allow a man to have more than one wife.” Black’s tongue-in-cheek comment was both a subtle insult to Frémont’s own family’s checkered history of marriage—he was himself the product of an illegitimate union—and a clever transformation of a perceived weakness into a political strength. Nevertheless, that Buchanan could accurately claim to have once been engaged (way back in 1819 to Ann Coleman of Lancaster), only to have lost her to an early death, went a long way in legitimating his bachelorhood and manliness. The story, one not uncommon among nineteenth-century bachelors, appeared sporadically during the campaign.

In an era where the reading public increasingly wanted to know the full biography of its presidential candidates, the Democracy did its best to extol Old Buck’s many years of public service and strong record of party principles. Perhaps less known to the public was Buchanan’s many intimate male friendships. As the biographer Horton acknowledged, no friend was closer to Buchanan than the Democratic senator from Alabama and fellow bachelor, William Rufus King. To many modern ears, the close friendship of these two bachelors has raised suspicions of a homosexual relationship (a matter still debated by historians). Yet, in its own time, their friendship was widely interpreted as emblematic of the kinds of cross-sectional friendship that had once formed the best tradition of political cooperation, hearkening back to the days of the Founding Fathers.

As summer turned to fall, the three-way race of 1856 remained as uncertain as any in recent memory. This uncertainty is reflected in the colorful political cartoons that commonly depicted the presidential election in a mixture, or mise-en-scène, of competing images. In the pro-Buchanan cartoon “The Buck Chase of 1856,” the Philadelphia illustrator John L. Magee shows Fillmore fallen to the ground, Frémont straddling two horses that he can’t control, and Buchanan literally as a buck deer racing ahead to victory (fig. 5). The image gestures toward the view that the agile, restrained manhood of Buchanan had outrun the slow, martial manhood of Frémont and moribund showing by Fillmore. Yet the underlying and perhaps unintended message was clear enough: the presidency was up for grabs.

By October, the election had largely been secured for Buchanan, and much of the nation breathed a sigh of relief. One last cartoon is telling, though, for how it registered Buchanan as a man and promoted an essential political conservatism. In “The Morning After the Election—November 1856,” a dignified Buchanan is seated under a trellis of grape vines near a field of wheat (fig. 6). The reference to Buchanan’s idyllic country home, Wheatland, is notable, since he had spent the entirety of the campaign there in continuation of the model of every presidential candidate since George Washington. The political message of the cartoon resonated with a gendered undertone:

the restrained manhood of a bachelor Democrat had defeated the martial pose of a bearded Republican and a blind Know Nothing challenger.

As is often the case the morning after an election, many questions remained. Why was Buchanan elected? What role did his bachelorhood play? Had competing visions of masculinity influenced the outcome of the 1856 election? Why hadn’t the barbate candidate and his beautiful bride beaten out the hardened old bachelor? And, at the end of the day, was Jesse Benton Frémont an asset or a liability, and why? Historians and political scientists have long debated patterns, motivations, and loyalties among voters. As with all presidential elections, the final vote tallies are revealing. Buchanan won soundly in the Electoral College, taking 174 votes to Frémont’s 114 and Fillmore’s 8, with an overall 45.3 percent of the popular vote to Frémont’s 33.1 percent and Fillmore’s 21.6 percent in the electorally rich battle ground states of the so-called Border North—Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, and especially Pennsylvania. In his home state, Buchanan also polled strongly among the traditional power base of the Democratic Party: Irish and German immigrants, Catholics, and urban mechanics and artisans.

In the end, the differences of gendered representations of manhood were not the determinative factor in the final outcome of the presidential election of 1856. Buchanan won not because of his restrained manly character but because of the strength of the Democratic Party among key voters in the Border North. Frémont lost not because the electorate rejected his martial beard but because a critical portion of them in the battleground states rejected the platform of the “Black Republicans.” Yes, in the election of 1856, not just James Buchanan but the Democratic Party won, and a resounding victory at that. On more symbolic levels, however, the Democrats had lost badly in 1856—for, on the gendered issues of beards, bachelors, and brides, they were on the losing side of the political battles in the years to come.

Although John C. Frémont’s brief political career ended in 1856 (future adventures as an embattled general during the Civil War awaited), beards would soon have their day in American politics. In fact, Frémont had set something of a barbate standard for future Republican presidential candidates. Famously, Abraham Lincoln began to grow a beard during his own presidential campaign in 1860 and kept his whiskers during the remainder of his presidency. So too, nearly every president from Ulysses S. Grant to William Howard Taft sported whiskers of some kind. The twentieth century witnessed reverses in this trend, with voters consistently preferring a clean shave to even the most meticulously groomed facial hair. Modern hirsute aficionados patiently await the return of the beard to the Oval Office, notwithstanding Donald Trump’s dismissal of challenges that his famous hairdo is anything short of the genuine article.

Bachelors, by contrast, have fared worse than beards. Ironically, it was the conservative Democratic Party that incautiously persisted in its love affair with bachelor candidates. When the next bachelor president ran for office (the Democrat Grover Cleveland in 1884), he also faced questions about his manhood and sexuality. But unlike Buchanan, Cleveland married soon after entering office. His marriage to the exceedingly young Frances Clara Folsom—he was forty-nine and she was twenty-one—scandalized the nation for but a minute, and put to rest whatever concerns Cleveland’s bachelor status may have raised. America has not yet seen another bachelor emerge as a major presidential candidate (the recent efforts of Lindsey Graham of South Carolina notwithstanding), but it has seen more than its fair share of May-December marriages in the White House. Donald Trump, who at age sixty-nine is twenty-four years older than his wife Melania Knauss Trump, would fit right in with Grover Cleveland, or for that matter the twice-married John Tyler—who in 1844, at age fifty-four, married the twenty-four-year-old Julia Gardiner.

Finally, there would be no stopping women from entering politics in the years ahead. The long-term effect of the beautiful bride Jesse Benton Frémont presaged the rising power of the First Lady in modern times, which culminated with the ascension of the inimitable Eleanor Roosevelt to the office. Even so, women would not win the right to vote until 1920 and have continued to be circumscribed in their access to public office (women still do not hold elected office in the same proportion as men). Even after women’s suffrage became law, no woman would become a serious presidential contender until the Republican Margaret Chase Smith in 1964 and arguably until Hillary Clinton in 2008. For all her beauty and charm, the example of Jessie Benton Frémont underscores that American voters do not vote based on looks alone. Equally so, the political limitations of feminine power in securing presidential elections underscores the gendered demands placed on American political leaders of both sexes to conform to a public conditioned to evaluating candidates through the lenses and expectations of masculine roles. It’s a lesson that the former First Lady and two-time presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has learned well, her famous pantsuits and short hair being her most obvious concessions to masculine comportment.

Times change and yet they remain the same. From this point of view, the bitter exchanges and personal attacks among Republicans and Democrats in 2016 are par for the proverbial presidential campaign course. But one cannot help be struck as well by the similarities on the levels of appearance and marital status of this season’s candidates to the contenders of 1856. Is Donald Trump’s mysterious coiffure and fake tan the equivalent of John Frémont’s beard? Is Hillary Clinton, a former secretary of state herself, another example of the Old Public Functionary? Are the Republicans’ promises of banning the immigration of Latinos and Middle Easterners the equivalent of the nativist views of the Know Nothings? And, ironically, is the looming presence of ex-President Bill Clinton the male equivalent to Jessie Benton Frémont? Much like the diverse images that compose the mise-en-scène of political cartoons produced during the presidential campaign of 1856, the election of 2016 is a mixed bag of gendered stereotypes and popular forms swirled about for maximum effect.

The election of 1856 was more than a final warning of impending sectional crisis or the last gasp of national political parties antebellum. It also represented a clash over sex and gender of the first order. Ultimately, the competition among Old Buck, Frémont, Fillmore, and their respective wives whether present or absent, underscores the fact that gendered and sexual performances still matter in politics today as much as, if not more than, they did 160 years ago. The more things change, the more they remain the same—the alchemy of beards, bachelors, and brides is to blame!

Acknowledgements

This essay grew out of a paper presented at the 2014 annual meeting of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic (SHEAR) in Philadelphia. The author would like to thank the participants of that panel, “Contest 1856: Year of Men, Year of Women,” especially Stacey Robertson, Rachel Shelden, Douglas Egerton, and John Belohlavek. In addition, the author would like to thank Michael Birkner, Michael Landis, Amy Greenberg, and the editors at Common-place for their insightful comments on earlier drafts.

Further Reading

On the election of the 1856, two chapters in edited collections are excellent starting points: Philip S. Klein and Roy F. Nichols, “Election of 1856,” in History of American Presidential Elections, 1789-1968, 9 vols., ed. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., and Fred L. Israel (New York, 1985) 3:1007-96; and Michael F. Holt, “Another Look at the Election of 1856,” in James Buchanan and the Political Crisis of the 1850s, ed. Michael J. Birkner (Selinsgrove, Pa., 1996), 37-67. See also William E. Gienapp, The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852-1856 (New York, 1987), 239-448; and Michael T. Landis, Northern Men with Southern Loyalties: The Democratic Party and the Sectional Crisis (Ithaca, N.Y., 2014), 148-168.

Web resources about the election of 1856 are few but important. See especially the Library of Congress’ “Presidential Election of 1856: A Resource Guide”; and Dickinson College’s “The Election of 1856.”

For a compendium of select campaign songs, see Irwin Silber, ed., Songs American Voted By (Harrisburg, Pa., 1971), and the wonderful collection of campaign songs at “Lincoln/Net” hosted by the Northern Illinois University Libraries. On political cartoons in early presidential contests, see Alan Nevins and Frank Weitenkamp, A Century of Political Cartoons: Caricature in the United States from 1800 to 1900 (New York, 1944).

On the role of gender in the Republican Party campaigns of 1856 and 1860, see especially Michael D. Pierson, Free Hearts & Free Homes: Gender and American Antislavery Politics (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2003). On bachelorhood more generally in the nineteenth century, see Howard P. Chudacoff, The Age of the Bachelor: Creating an American Subculture (Princeton, N.J., 1999). The most complete biography of James Buchanan remains President James Buchanan: A Biography (Newtown, Conn., 1962). A recent biography of the Frémonts is Sally Denton, Passion and Principle: John and Jessie Frémont, the Couple Whose Power, Politics, and Love Shaped Nineteenth-Century America (New York, 2007). On the Know Nothings, consult Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s (New York, 1992). On voter motivation more generally, see Glenn C. Altschuler and Stuart M. Blumin, “‘Where Is the Real America?’: Politics and Popular Consciousness in the Antebellum Era,” American Quarterly 49:2 (June 1997): 225-67.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.4 (September, 2016).

Thomas J. Balcerski is assistant professor of history at Eastern Connecticut State University. He is currently working on a book project titled “Siamese Twins: The Intimate World of James Buchanan and William Rufus King.”