Before Photography: Visualizing Black Freedom

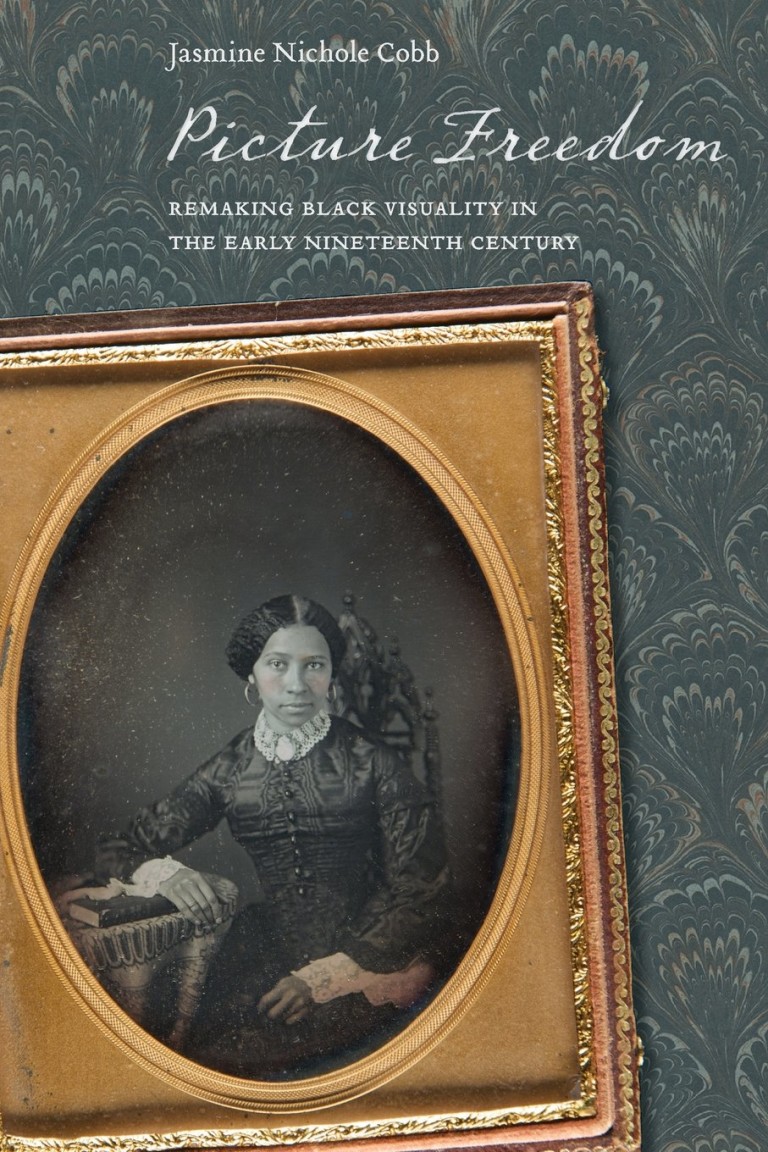

Jasmine Nichole Cobb’s Picture Freedom begins by examining a daguerreotype in the Dickerson family collection at the Library Company of Philadelphia, the same early photographic portrait of an African American woman illustrating the book’s cover. Cobb reads the sitter’s fine clothing and jewelry, her upright pose and hand-tinted cheeks, as well as the studio furnishings and books visible in the portrait as evidence of black self-making and self-possession before the abolition of U.S. slavery in 1865. While the daguerreotype’s maker remains unknown, Cobb asserts it to be Robert Douglass Jr., a black daguerreotypist active in Philadelphia in the 1840s and 1850s. Attributing the portrait to Douglass allows Cobb to see it as the co-production of two free black subjects who rejected popular, degrading images of African Americans under slavery and “seize[d] control over representation of the free Black body” (3).

The five chapters in Picture Freedom never return to an analysis of daguerreotype portraiture, yet Cobb’s understanding of early photography as an especially potent visual technology for the expression of black agency motivates her analysis of “racial caricatures, lithographs, abolitionist newspaper writings, runaway notices, sentimental literatures, joke books, and scenic wallpaper” (20-21). According to Cobb, these popular visual media, which circulated across the Atlantic world “between the years of gradual emancipation laws emerging in 1780 and the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850” (6), together “create a more robust depiction of Black freedom in the transatlantic imaginary” (21). Cobb laments the fact that few studies have focused on visual representations of black freedom before the daguerreotype, while at the same time she acknowledges the recent surge of scholarship on early photography and African American self-making. Indeed, major publications in the last decade have presented photography as exceptionally capable of visualizing black agency before the Civil War, including Pictures and Progress: Early Photography and African American Identity, edited by Maurice O. Wallace and Shawn Michelle Smith (2012), Marcy Dinius’s The Camera and the Press: American Visual and Print Culture in the Age of the Daguerreotype (2012), and Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, edited by John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier (2015). Cobb returns briefly to early photography in chapter 4 of Picturing Freedom (161), referring to Frederick Douglass’s faith in the medium’s democratic character, but only to underscore the importance of popular print media in managing the depiction of black freedom. This shift in focus becomes one of the book’s important contributions to the study of race and representation.

Reflecting Cobb’s interdisciplinary training in communication studies, Picture Freedom explores the social history and cultural uses of nineteenth-century popular images while framing them in terms of twenty-first-century critical theory. Two key theoretical concepts run through the chapters. Cobb includes the first of these, black visuality, in the book’s title, a term that brings to mind recent work on black bodies and performance by Nicole Fleetwood, Leigh Raiford, Anne Anlin Cheng, and others. The introduction to Picture Freedom offers a broad definition of black visuality, explaining that it refers to “the entire sum of the visual as experienced by people of African descent” (9). Both “psychic and subjective,” it “pertains to the Black figure’s awareness of how she was perceived, and the sense of possession she felt toward her own body that allowed her to master and manipulate outward constructions of her visibility” (9-10). Cobb coined the second key concept, transatlantic parlor, by drawing from critical theories of race, studies of the transatlantic slave trade, and cultural histories of the bourgeois parlor or drawing room as a significant site for the performance of gender, class, and race in the nineteenth-century United States.

The transatlantic parlor proves to be a slippery metaphor in Picture Freedom, one to which Cobb returns repeatedly in order to refine and contextualize. The introduction describes it as “a place for dissimilar groups of people and cultural producers to convene around visions of Blackness separated from slavery” (13). It further presents the transatlantic parlor as a discursive space that imagined the Atlantic world as a “unified home of slaving empires and a place for domesticating presumably uncivilized Africans through enslavement” (17). Subsequent chapters use the parlor as a potent metaphor for “the United States as a home interior” in which white middle-class Americans pictured themselves as citizens and imagined others as unfit for belonging; the book also shows how this theoretical concept inhabited physical spaces and material forms of visual communication. In chapter 3, for instance, we learn that the drawing rooms of white bourgeois homes in antebellum Philadelphia “served as places of retreat where Whites coped with the changes of gradual emancipation” (111). By analyzing “Life in Philadelphia,” a lithographic series created by Edward Williams Clay in 1828, Cobb shows how white people in their parlors ridiculed the speech, clothing, manners, and social aspirations of free blacks, and especially black women, “in order to manage anxieties about sharing northern spaces with free Black people” (113). Well-known to cultural historians but rarely studied in detail, Clay’s series comes back as the subject of chapter 6, where Cobb explores its circulation in the United States, Britain, and France. She thus returns to the idea that bourgeois white subjects sought to bring black people “under control through display, through their re-presentations on the printed page and the location of these prints within the home” (193), and to domesticate them in a specifically transatlantic parlor.

Picture Freedom, however, investigates not only whites’ construction of black visuality in the figurative parlor but also African Americans’ efforts to appropriate popular images of blackness and experiment with self-representation. We see the latter interest in chapter 2, where Cobb turns to free blacks’ establishment of their own parlors in northern American cities. She specifically considers the creation of friendship albums as a significant parlor activity that African American women undertook to perform their free selves. The chapter opens with a single page from a friendship album that belonged to a young African American girl—a member of the Dickerson family, like the sitter in the daguerreotype with which Picture Freedom began. On that page the girl’s schoolteacher drew a fuchsia plant, copied from a flower-painting manual, and paired it with a poem that invites the reader/viewer to seek out the inner beauty of the flower, which droops its head in a demonstration of modesty. In Cobb’s view, we must read images and writing like these in black women’s friendship albums as more than mere “floral motifs and saccharine sentiment” (109). Although modeled on white women’s parlor practices, the pages of the Dickerson album “offered thoughts on free Black women’s bodies, the experience of freedom and new practices of spectatorship…” (69). They thus challenged the exclusion of black womanhood from dominant bourgeois society and its specific notions of beauty.

As a historian of art and visual culture, I appreciated Cobb’s effort to tie her theoretically informed claims about black freedom to specific images. Enacting the imperative in the book’s title, almost every chapter opens with a poignant picture: from the daguerreotype in the introduction, to an amateur painting of a free black woman in chapter 1, the floral album page in chapter 2, and lithographs caricaturing African Americans in urban public life in chapters 4 and 5. For each key visual example, Cobb describes the subject matter and historical contexts in which the image circulated before the abolition of U.S. slavery. Such information ends up dominating many of her interpretations, however, leaving the reader with questions about how the visual characteristics of the pictures themselves contributed to the social, cultural, and political work Cobb attributes to them. In her discussion of Clay’s “Life in Philadelphia” series, for example, Cobb spends considerable time deploying critical theory, cultural histories, and period sources to show how free black Philadelphians represented their freedom through personal dress and the built environment, especially the space of the black church. This context, she argues, motivated Clay’s series and found expression in the subjects and captions of his lithographs. But how did those prints signify visually, and in relation to other images, in the early nineteenth century? How did Clay’s rather naïve style of rendering figures, his method of delineating the physiognomy and comportment of black bodies, his use of complex iconography, and his application of color to each scene work together to undermine notions of black respectability, femininity/masculinity, and citizenship?

Picture Freedom concludes as it began, with a photograph. Instead of a daguerreotype portrait from the museum’s beginnings, it considers a press photograph of Barack Obama delivering a speech in the White House in 2009. This key image in the book’s epilogue also brings readers back to the politicized parlor, in all of its complexity. For within the lavish interior of the White House, occupied by the first black U.S. president and his family, Americans can now reimagine the nation as “a home for racial diversity” (223). Through the global circulation of photographs of a black man presiding over the White House parlor, Cobb observes, the United States presents itself to the world as a bastion of freedom and equality, and effaces its history of slavery and racial prejudice.

Picture Freedom reminds scholars who study race and American visual culture how important it is to keep that long and troubling history in view. The book further challenges its readers to rethink what it meant to picture black freedom and citizenship—well before the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment and before the advent of photography.

This article originally appeared in issue 16.2.5 (Spring, 2016).

Tanya Sheehan is associate professor and chair of the Department of Art at Colby College, where she teaches American art history. She has published widely on the history of photography and African American visual culture.