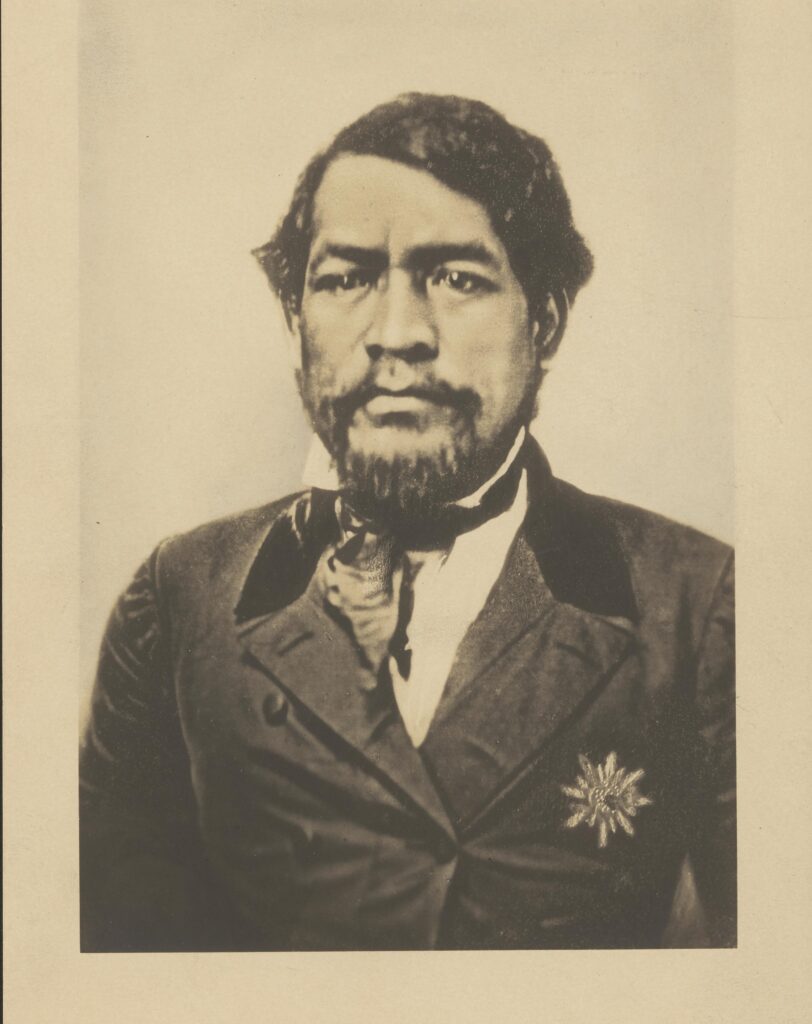

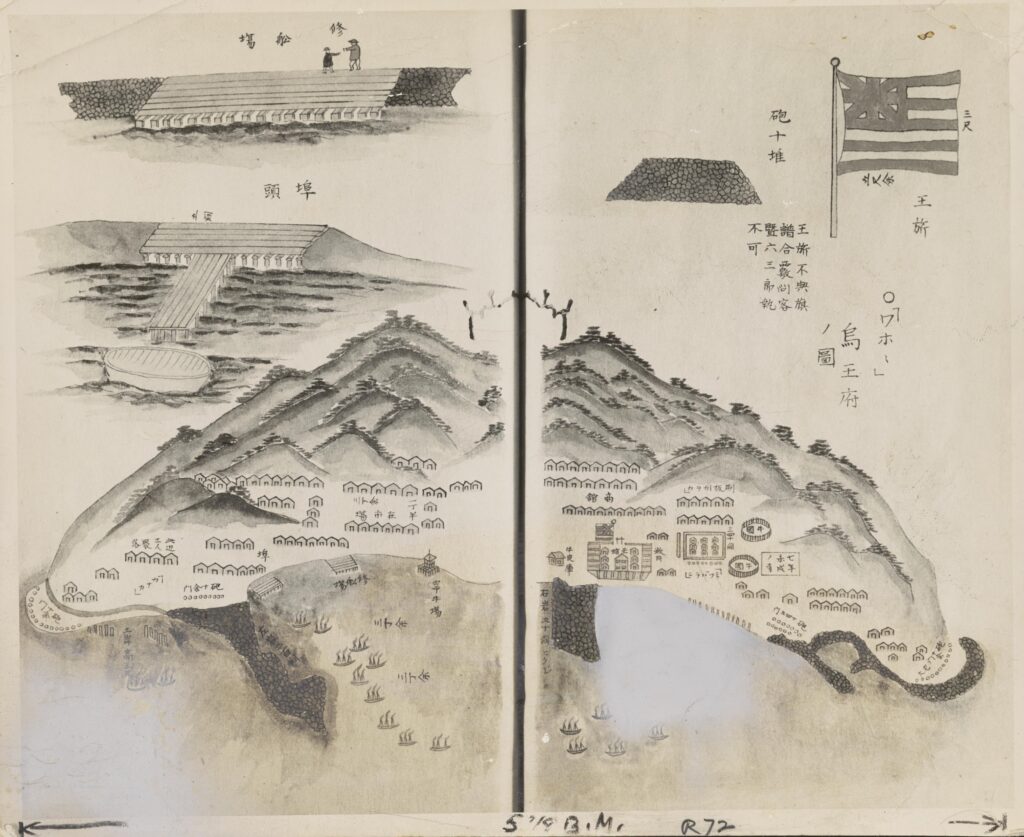

The story is not yet over. By 1860, Heco and Manjiro were both back in Edo, among the very few people fluent in both English and Japanese. The primary European language then known in Japan was Dutch. Heco, an American citizen, got a job in the new American consulate in Kanagawa. He also founded the first (though short-lived) Japanese newspaper, having seen in San Francisco, Honolulu, and elsewhere how this medium resulted in the rapid spread of news throughout the population. He also established an import/export business, primarily with San Francisco contacts. Manjiro, on the other hand, was appointed as interpreter in 1860 to the first official embassy of the Empire of Japan to the United States of America.

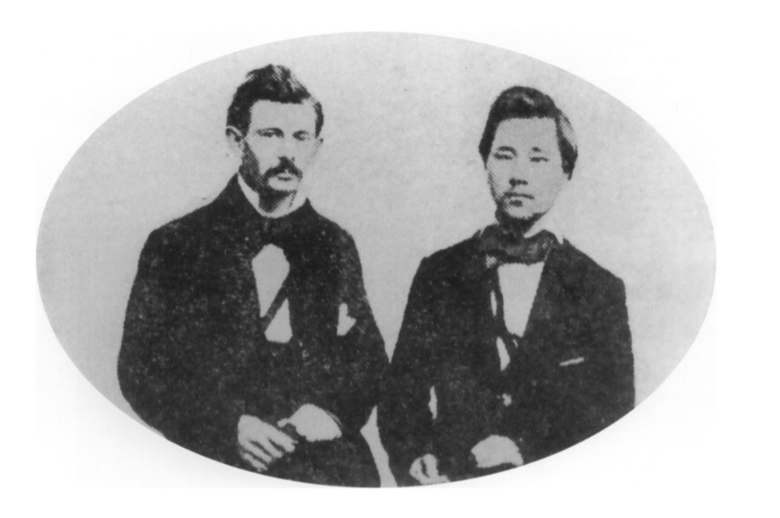

And we still have the gannenmono, impossible without Perry’s missions. The negotiations with the Japanese government to bring workers to Hawai’i were carried out by Heco’s good friend from San Francisco, Eugene Van Reed, who would go on to become Hawai’i’s first consul general to Japan. The two friends left San Francisco for Japan, stopping in Honolulu, where Heco, who had been seasick most of the trip, stayed behind for a time to recover before eventually returning to his homeland.

Further Reading:

Chamberlain, Levi, “Journals, 1822-1949” (typescript copy), Vol. XVI, November 5, – August 14, 1832. Hawaiian Mission Children’s Society Library.

Kawada, Ikaku, et al. Drifting toward the Southeast: The Story of Five Japanese Castaways: A Complete Translation of Hyoson Kiryaku (a Brief Account of Drifting toward the Southeast) as Told to the Court of Lord Yamauchi of Tosa in 1852 by John Manjiro (Spinner Publications, 2004).

Kono, Hideto and Kazuko Sinoto, “Observations of the First Japanese to Land in Hawai’i,” The Hawaiian Journal of History, 34 (2000), 49-63.

Oaks, Robert F., “Golden Gate Castaway: Joseph Heco and San Francisco, 1851-1859.” California History, 82, no. 2 (2004): 38–58, 63–65.

Plummer, Katherine. The Shogun’s Reluctant Ambassadors: Japanese Sea Drifters in the North Pacific (Portland: The Oregon Historical Society, 1991).

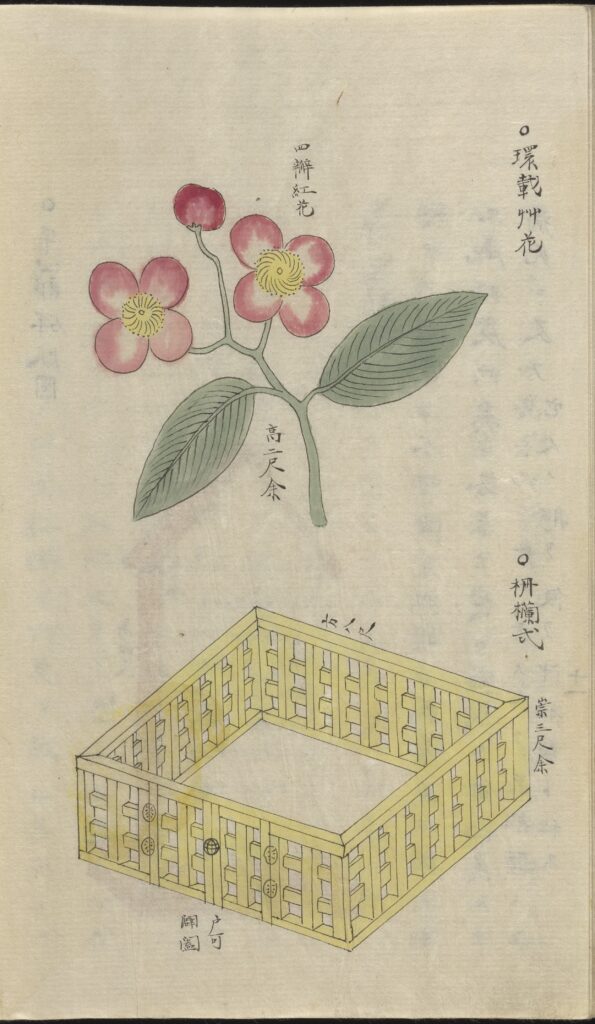

Plummer, Katherine, trans. A Japanese Glimpse at the Outside World 1839-1843, ed. Richard A. Pierce (Kingston, Ontario and Fairbanks, Alaska, The Limestone Press, 1991).

This article originally appeared in December 2024.

With a PhD in Colonial American history from the University of Southern California, Robert F. Oaks taught for several years in Texas and California. Unable to attain a tenured position, he re-invented himself as a pseudo techie and worked for many years at Bank of America in the technology division. Upon retirement, he returned to his love of history, though now more interested in Asian and Hawaiian history. He now lives in Honolulu with his husband.