Benjamin Franklin Slept Here

The confession is clear and unrepentant: “I bored a very small hole through the wainscot in the seat of my window.” And so this historian went hunting for that historic act of vandalism. The vandal in question, Benjamin Franklin, put the hole in his landlady’s house on Craven Street in London, where he lived for two extended stays between 1757 and 1775. Remarkably, the house still exists (fig. 1), the only Franklin residence that does. His humble birthplace in Boston was long ago swept away, as was the grand suburban house he rented at Passy just outside Paris. His Philadelphia townhouse still stands but is a mere shell, a well-swept ruin. In contrast, the house on Craven Street withstood Franklin’s modifications as well as several historic crises. Why does any piece of the past survive? To an unsettling degree, it’s a matter of luck. Franklin’s house has been very lucky. And lucky us, to have inherited from the past such a revealing artifact of the long, complicated connections between Britain and America.

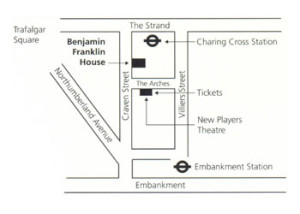

The area around Craven Street is now known for its dominant structures: Charing Cross Station, Trafalgar Square, and the National Gallery just north of the square (fig. 2). The neighborhood was different in the eighteenth century. It had escaped ruin in the Great Fire of 1666 and benefited from the rebuilding that followed that disaster. Londoners wanted houses built of stone rather than flammable timber, and those who could afford it wanted to live on streets shielded from the bustle of shops and public life.

Craven Street was a typical result: a row of residences, in this case Georgian townhouses, near businesses but not among them. To the north, it encountered the Strand, which led to several cultural centers, including the Royal Society of Arts, to which Franklin belonged. The Strand also ran down to Westminster’s government offices, where Franklin went to lobby for Pennsylvania and the other colonies he represented. The south end of Craven Street terminated on the Embankment along the River Thames, a great convenience in a city that still used the river for everyday transport.

The house where Franklin lived was built around 1730 and owned by the Stevenson family. Rising four floors above a cellar, it is tall and narrow. Whereas an older house might have had a great room where visitors entered, meals were taken, and servants slept, this modern house had many smaller rooms with distinct functions—entertaining, dining, or sleeping. From the widowed Margaret Stevenson, who lived with her daughter Mary (or “Polly”), Franklin rented a bedchamber and sitting room on the story just above the street, though he also entertained visitors in Mrs. Stevenson’s parlor on the ground floor.

In fact, he pretty much took over the house. The Stevensons quickly learned that their lodger was eminent, charming, and amazingly well connected. Letters from many notables were addressed to “Mrs. Stevenson’s / in Craven Street.” Guests to the house included George Whitefield (the famous preacher), Israel Wilkes (brother to political firebrand John Wilkes), William Strahan (the printer who published Samuel Johnson’s dictionary), John Pringle (the King’s physician and later president of the Royal Society), and Joseph Priestley (clergyman and chemical experimenter).

The many men of science hint at Franklin’s continued interest in the wonders of nature. When he and Sir John Pringle visited the German speaking countries in 1766, Franklin discovered “pulse glasses,” tubes of glass filled with alcohol and sealed with a slight vacuum. The devices registered small changes of temperature—slight warmth made their contents bubble. Franklin employed London instrument makers to fashion even more sensitive versions; to test these he bored that hole near a window. Even with the top of the tube exposed to the window’s draft, the warmth of the room (Craven Street had many fireplaces [fig. 3]) made bubbles rise, “to the no small surprise,” Franklin exulted, of the “philosophical spectators” who were unfamiliar with the device. (One wonders whether Mrs. Stevenson was philosophical about the damage to her wainscot.)

A steady train of Franklin’s relatives came to Craven Street. Some of them bore American groceries for the homesick Philadelphian. Codfish, pippin apples, cornmeal, and ham were among the delicacies that Franklin shared with the Stevensons, who became for him a kind of surrogate family. While Franklin’s son William studied law in London, he too resided in the house (along with his and his father’s slaves, Peter and King). Franklin and Mrs. Stevenson thought William and Polly might marry each other, but the union was not to be.

Franklin carried on an affectionate correspondence with Polly and gave her away at her wedding to Dr. William Hewson in 1770. He and Polly used their letters to discuss scientific topics. He proposed various experiments she could do in the Craven Street house and its garden. And he published eight of his letters to her in the fourth edition of his Experiments and Observations (1769), advertising his conviction that women, no less than men, could master science.

When Mrs. Stevenson was away for a week in 1770 and the Hewsons kept the house for Franklin, he wrote the comical “Cravenstreet Gazette” to document the chaos while “Queen Margaret” was away. The subjects of her kingdom, especially “Dr. Fatsides,” the “Great Person,” groaned under the “corrupt, ignorant, blundering, foolish, crafty, and Knavish Ministers,” meaning Dr. and Mrs. Hewson. I hope the ministerial Hewsons saw the humor in Franklin’s very timely satire of British government: “If these nefarious Wretches continue in Power another Week, the Nation will be ruined—Undone!—totally undone, if the Queen does not return.”

Peace returned more quickly to Craven Street than to Britain and its empire. Franklin left London in 1775, for the big, obvious reason. He would formally break with Great Britain the next year, when he signed the Declaration of Independence. He nevertheless managed to keep in touch with many British friends, including the Stevensons, who loyally forwarded household items he had, in his haste, left behind.

After Franklin’s departure and Mrs. Stevenson’s death, the neighborhood around Craven Street changed yet again. The creation of Charing Cross Station, which opened in 1864, required demolition of several streets south of the Strand. Craven Street is now the western boundary of the station—had the railroad terminus needed more space or been differently configured, the street might not have survived. The station’s dirt, noise, and traffic sent middle-class Londoners packing. Many of the houses on Craven Street became hotels for travelers. (Herman Melville stayed at number 25 for two months in 1849.) In such boarding houses, existing rooms were cut up; Georgian architectural details were covered over or removed; overuse and damage went unattended. Still, the street survived the Blitz of World War II, the worst disaster to strike the city since the Great Fire. The Germans bombed the National Gallery and Trafalgar Square, both of which were damaged, as was Charing Cross Station.

At some point in the twentieth century, the Craven Street house was abandoned and left dangerously unrepaired (fig. 4). Even so, the Franklin connection remained known and, sometime before the 1930s, the London City Council put up a bronze plaque commemorating his residence at what is now numbered 36 Craven Street (fig. 5). The dark bronze tablets were early versions of what are now the eye-catching blue plaques that dot buildings throughout London, marking spots where famous people lived (as with the one that notes Melville’s stay at 25 Craven Street). Anyone who consulted a guide to the blue plaques would know where to find Franklin’s house and could go gaze upon its neglected exterior.

It is neglected no more. The Friends of the Benjamin Franklin House, who recently acquired the structure, raised money for its renovation, and reopened it to the public in 2006, the tercentenary of Franklin’s birth. They saved the building—the house was in danger of collapse and might have brought down the houses on either side of it. The interior required much painstaking attention (fig. 6) to restore a semblance of the house Franklin would have known.

Even with all the restoration, Franklin probably would not recognize his London home. It has almost no furnishings (fig. 7). Visitors to historic sites love to look at stuff: the impossibly big soupspoons from which our ancestors supped, the ridiculously high beds into which they clambered and slept, the upliftingly large tomes with which people in a pre-internet society whiled away the long, empty hours. What things the Craven Street house does have are not even associated with Franklin; not so much as a stray button or tattered pamphlet remains from this most famous occupant.

The curators have three clever solutions. First, visitors go down to the cellar to view an introductory film and look at the few artifacts associated with the house. The film is a brisk overview of Franklin’s life and accomplishments; the artifacts are mostly meant to explain the startling discovery, during renovation, of human bones in the cellar. No, Dr. Franklin was not the Sweeney Todd of Craven Street. Rather, Dr. Hewson (Mrs. Stevenson’s son-in-law) did anatomical research at the house. Franklin regarded him as a fellow man of science and approved his diligent pursuit of knowledge, which proved fatal—Hewson accidentally cut himself during a dissection and perished of septicemia. Bones left from his investigations are displayed alongside period medical instruments.

Visitors next meet “Polly Stevenson” (fig. 8). I braced myself. Despite a delightful encounter with “Edward Winslow” at Plimouth Plantation many years ago, I generally hate it when some tall, well-nourished person, visibly equipped with a mouthful of gleaming white teeth, tries to convince me that he or she is a Viking, or whatever. But the actress who played Stevenson was quite convincing, especially in her performance of the eighteenth century’s balance between formality and sentiment. Stevenson explains the coming rupture between her country and Franklin’s as both a national and a personal tragedy. This approach would appeal to British and American visitors alike because it personalizes a grand historic event and reinforces the “special relationship” between Britain and the United States. Yet even as “Polly Stevenson” laments the likely loss of her friend, she calls him “Dr. Franklin,” never stooping to the gropingly familiar “Ben,” the anachronism American tour operators love to use.

Finally, there is an audiovisual show. Slides project onto the walls various images, contemporary and modern, of places and things to which the soundtrack refers. Enter Mrs. Stevenson’s parlor and you can hear William Strahan and John Pringle (they’re the ones with the Scottish accents) stir their tea and gossip with the lady of the house. Margaret Stevenson is played by Imelda Staunton, star of Vera Drakeand the newest Harry Potter movie. I applaud Peter Coyote’s patriotism in performing Benjamin Franklin but cringed at his midwestern accent. Franklin probably had a New England accent, acquired from his Nantucket mother. (Imagine the Mayor Quimby character on The Simpsons as Benjamin Franklin.)

After my tour of the house, I lingered with one of the curators to inspect the wainscot around the windows, looking for that historic vandalism. Alas, Franklin’s designations of a “small hole” and “my window” were maddeningly vague. (How small? Which window?) Assuming that Franklin’s philosophical spectators had not crowded into his bedchamber, I focused on his and Mrs. Stevenson’s sitting rooms. But the renovators had carefully painted over any minor damage, which might, in any case, have been repaired once Franklin had put away his pulse glasses.

Thousands of visitors have now seen the house on Craven Street, including hundreds of British schoolchildren. The kids get a double dose: science (Dr. Franklin’s electricity and Dr. Hewson’s anatomy) and history (a calm assessment of Britain’s long history of gaining and losing colonies). Tour guides squarely address serious historical problems, including chattel slavery. And the site is interestingly presented as a crossroads for the varied people, commodities, and ideas of the Atlantic world. It’s one of the few places in London that embraces Britain’s colonial American past, even to the point of celebrating the Fourth of July this year, complete with cake and champagne.

But London faces new threats. The impending Olympic Games will channel National Lottery funds toward sports and away from museums such as the Franklin house—every London curator is worried about budget cuts. Much more dangerously, terrorists have targeted London since the start of the Iraq War. The area around Craven Street was unaffected by the July 2005 transport bombings, but one of the two gas-packed Mercedes-Benzes detected in London this summer was parked near Trafalgar Square. It may be a matter of luck that certain pieces of the past have come down to us, but luck shouldn’t be the only reason it happens.

This article originally appeared in issue 7.4 (July, 2007).

Joyce E. Chaplin is James Duncan Phillips Professor of Early American History at Harvard University and the author of The First Scientific American: Benjamin Franklin and the Pursuit of Genius (2006). She is currently working on a history of circumnavigation.