Beyond Baked Beans

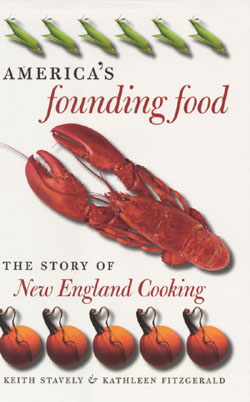

America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking, by Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald, is an ambitious culinary history “that chronicles the region’s cuisine from the English settlers’ first encounter with Indian corn in the early seventeenth century to the nostalgic marketing of New England dishes in the first half of the twentieth century” (inside cover). Librarians and independent scholars, this husband-and-wife team explores New England foodways using three centuries of culinary, historical, and literary sources as well as an impressive array of secondary sources. Subtitle aside, America’s Founding Food moves beyond the realm of the kitchen and cookery to explore the Anglo-American society in which these foods were prepared, consumed, and eventually celebrated.

The title of the book is sure to provoke some well-deserved debate in food history circles. The cookery of New England has no more claim to the title of “America’s founding food” than other early regional cuisines. Curiously, despite the bold title, the authors make no attempt to look at the influence or place of New England cookery outside of the region. Such a discussion might have more fully justified the title.

America’s Founding Food is organized around New England’s foodstuffs with an emphasis on the dishes that have become icons of the region: Indian pudding, Johnny cakes, baked beans, and pumpkin pie. In addition to chronicling the evolution of classic New England recipes and foods, the authors explore what these dishes meant to the people who ate them and the reasons why “such culinary wallflowers” were elevated to “virtually canonical status” (2) in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Happily, the authors also spend time looking at some of the lesser-known foods that—despite their past popularity—have fallen by the culinary wayside. (Just when was the last time you were offered a wedge of savory eel pie or a slice of Election Cake?)

The most significant accomplishment of America’s Founding Food is the truly impressive collection of lively and illuminating primary-source accounts. The book is worth reading for this alone. The narrative that weaves these accounts together relies quite heavily on a wide range of secondary sources. The notes at the end of the book are excellent, and those interested in New England history may find themselves flipping back and forth between these notes and the book’s text.

While America’s Founding Food is arguably the best survey history of New England foodways to date (there are better works that deal with narrower subject matter), there are some problems with the book that are difficult to overlook. For example, there are a number of occasions when the authors’ interpretations are flawed or incomplete. “For their own victuals the English considered cod ‘but coarse meate,’” the authors claim, quoting from a contemporary source. “But by the eighteenth century, the cash-producing fish had become a featured item on wealthy colonial tables” (115).

Did the colonists initially disdain cod? A reading of the original quote from Edward Winslow, included in A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, Mourt’s Relation (New York, 1963), reveals a far different picture: “I make no question but men might live as contented here as in any part of the world. For fish and fowl, we have great abundance; fresh cod in the summer is but coarse meate with us; our bay is full of lobsters all the summer and affordeth variety of other fish; in September we can take a hogshead of eels in a night, with small labor, and can dig them out of their beds all the winter . . . ” Here, in fact, is a colonist reveling in a land so bountiful that normally valuable fresh (i.e., not salted) cod became mere “coarse meate . . . “

In this same vein, a lack of familiarity with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Anglo-American foodways lead the authors to erroneously claim that butter was “a novel flavoring” in the mid-1600s and that the presence of butter in an eel recipe “distinguished this recipe as an eighteenth-century creation” (82-83). And, despite the authors’ best intentions to avoid the “fakelore” of much earlier work about New England foodways, they too repeat some old saws. For example, we are told that an unfired hearth was viewed with disapproval and “only an inattentive housewife would allow her fire to burn out completely” (13). The narrative is peppered with these small but troubling errors.

More troubling than these small errors is a provocative but largely unsubstantiated interpretive thread running through the narrative. Stavely and Fitzgerald contend that colonials rejected the adoption of “savage” Native foods. The notion that the colonists resisted indigenous foodstuffs makes its first appearance in the chapter about corn. The authors argue that “if the advent of the English was designed to move the New World from barbarism to civilization, then the fact that the civilizers were subsisting on the savages’ food was, at a minimum, highly embarrassing.” Further, the authors claim that a “lack of discussion of Indian corn in early accounts” supports their contention (12).

This interpretation may be novel and intriguing, but the authors provide little documentation to support these claims. In fact, they make this argument in the face of substantial evidence to the contrary. Early New England sources are full of laudatory references to corn as both a food and trade commodity. John Winthrop, in his 1662 Letter to the Royal Society (reprinted in New England Quarterly Vol. X No.1 [1937] p.121-133), wrote that corn “is now found by much Experience, that it is wholesome and pleasant for Food of which great Variety may be made out of it.” These accounts make it clear that the colonists quickly incorporated corn into their diet and used the new grain in traditional English ways as a bread grain, porridge, or a thickener in meat stews. What is hard to glean from these New England accounts and the author’s own arguments is substantial evidence for a “suppressed connection of the cuisine to Indian foodways” (278).

Despite these criticisms, America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking is important reading for people interested in the history of New England and its food. Given the unevenness of the primary-source record and some substantial gaps in available information, writing a survey history of New England foodways is truly a daunting task. These authors have done considerable work that will undoubtedly spark further scholarly and popular interest in the subject.

Further Reading:

Saltwater Foodways: New Englanders and their Food, at Sea and Ashore, in the Nineteenth Century (Mystic, Conn., 1995) by Sandra L. Oliver is unquestionably the best work yet written about New England foodways. Oliver’s clearly written, carefully researched, and award-winning book is filled with primary-source accounts and insightful commentary, and it includes nearly two hundred recipes (with helpful notes for modern cooks) for readers who truly want to savor the past. In the spirit of full disclosure, Sandy Oliver is a friend and the co-author of my upcoming book. Another useful source is Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (New York, 1981), transcribed by Karen Hess with “historical notes and copious annotations.” Hess’s introduction to the book and thorough recipe commentary is must reading for anyone interested seventeenth-century Anglo-American food history.

This article originally appeared in issue 6.1 (October, 2005).

Kathleen Curtin, is Colonial Food Historian, Plimoth Plantation, and co-author of Giving Thanks: Thanksgiving Recipes and History from Pilgrims to Pumpkin Pie (New York, 2005).