Black Girlhood in Early American Children’s Print Culture

In the texts of African American women writers, children learn lessons in survival, self-reliance, fortitude, and determination. In contrast, in literature written by white authors, black girls suffer and/or die. In these white-authored narratives, white women characters clothe, educate, and reform black girls by exposing them to teachings from the Bible, all acts that reinforced the image of the benevolent white female. This stereotype is presented in the most popular white-authored black girl figure, the enslaved black girl Topsy in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852). In the novel, when the white mistress, Miss Ophelia, asks the enslaved Topsy where she originated from, Topsy replies that she “jes’ growed,” making no mention of parents. Miss Ophelia becomes the white surrogate mother figure who reforms Topsy. Through tutelage in religion and manners, Topsy matures from an untutored girl to a missionary who eventually leaves the United States to teach abroad in Africa. The writings of black women revised this mid-nineteenth-century narrative and created representations of black girls who learned to acquire an education through alternative means, sought reform movements that they chose on their own, found ways to become self-sufficient, and used their achievements to strengthen their own homes, attain freedom from danger, and ensure their survival.

The formula of white benevolence toward black girls exists in an earlier, lesser-known text, The Tawny Girl; or the History of Margaret Russel, Illustrating the Benefits of Education on the Most Degraded Classes of Society (1823), by an anonymous author. Textual details point to white authorship: the book was published at a Quaker press that often published abolitionist literature. The use of the word “degraded” in the title is another clue. It would be hard to imagine a black writer using this word to describe his or her protagonist. But if we imagine a white writer, the word signals an idealized trajectory from poverty to a better state (whether the improvement is moral or economic is left ambiguous in this title). The title also suggests that behind the scenes is a white benefactor who will help the “degraded” black girl improve herself.

Although The Tawny Girl was first published in England by W. Alexander & Son in 1822, Samuel Wood, a Quaker teacher-turned-publisher and children’s book author, reprinted The Tawny Girl in New York the next year at his publishing firm, Samuel Wood and Sons. His company published children’s books that were “seemingly devised to be instructive and moral.” Nearly all of them had a strong Christian message. The American primers and books Wood chose to reprint offered suitable reading for black children without traits of racial bias. Wood, who was greatly influenced by the children’s books that were popular in England, decided that many children’s books published in the United States were unsuitable for young readers. He installed a small printing press in the rear of his store and printed children’s books of his own compilation and authorship. His first title, published in 1806, was The Young Child’s ABC, or, First Book, which sold for three cents. By 1813, he had written and published over fifty books. Wood said that in making his selections, “he tried to avoid anything that would tend to corrupt the innocence of the youthful mind, and care was taken to void selections that would lead to a taste for the exhibitions of the stage.”

To our eyes today, the books Wood published might seem dull and didactic, but they were in high demand in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. Wood believed in moral suasion, the idea that children could be influenced by moral arguments and good examples to do right, in contrast to a reliance on punishment and threats of punishment that had characterized child-rearing in the eighteenth century. Wood’s books taught children that they should always make the good and useful choice. They also presented the uncomfortable issues of the times to youthful readers, including racial inequality and economic injustice. The portrayal of a mixed-raced girl in The Tawny Girl (1823) is an example of Wood’s interest in publishing books with themes of social issues.

The Tawny Girl is a short novel that tells the story of an eight-year-old mulatto girl named Margaret Russel who is born in Ireland. Margaret eventually is forced to sell matches to care for her sickly white mother after her father, an African, dies and leaves his family impoverished. The Tawny Girl opens when Margaret, her mother (an Irish servant), and her father (a servant to an Irish man) move from Ireland to Liverpool, England, to escape poverty. When the father falls ill and dies, Margaret’s mother takes up residence in Warrington, England, where she obtains a basket and becomes a “tradeswoman” selling matches and “vending wares of small value, such as pins, tape, &C.” Margaret and her mother move again, this time to York, where “as is customary with such wanderers, they put up at one of those places of wretchedness, a common lodging-house.” Living in near poverty, the mother continues to sell matches while Margaret tries to sell her mother’s goods from door to door. In her efforts to escape poverty, Margaret “range[s] the streets, only one step removed from a common beggar.”

Through the benevolence of a group of neighbors, Margaret is given a chance to enter school. She is at first rejected for fear that due to “her wandering life and probably dissolute habits, she might bring discredit on the school,” but Margaret finally is admitted and is soon accepted by her classmates. Despite her hardships Margaret learns her lessons and commits passages from the Bible to memory, which pleases her teacher. Mother and daughter eventually move to a crowded almshouse. However, concerned that her daughter’s mind and body “might . . . be contaminated by the conversations and habits of the lodging-houses,” Margaret’s mother obtains “a wretched garret.” Margaret tries to make friends but is ostracized when she must sell matches and obtain food to care for her sickly mother, who eventually dies. The daughter “bitterly lamented her destitute and forlorn situation;—she was left to struggle with the world, without any natural protector, at a dangerous age, being in her fourteenth year.” Margaret is relieved when benevolent neighbors in the community intervene to assist by housing her, clothing her, teaching her the Bible, and becoming surrogate parents. However, at the age of sixteen Margaret dies after lengthy illness and much suffering. Margaret’s suffering—the loss of both parents, extreme poverty, labor in the streets at fourteen, and death at sixteen—vividly describes for young readers about the hardships of abject poverty, loneliness, and illness as a means of encouraging empathy for others. In the hands of an abolitionist publisher, those others included blacks.

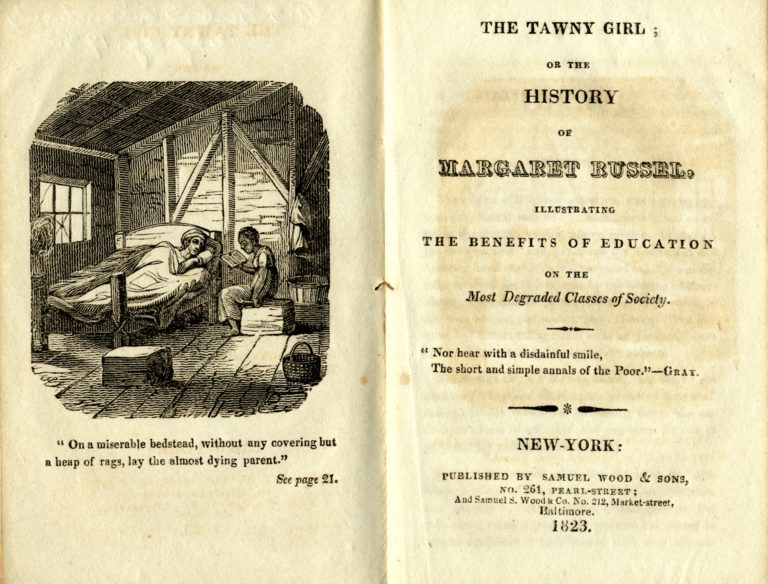

The wood-engraved frontispiece of The Tawny Girl features a black girl (Margaret) reading to a white woman (her mother), who is lying on a bed in a shabby garret. The artist, Dr. Alexander Anderson, was a white man who began his career as a doctor but left the field of medicine to become a wood engraver. The technique of wood engraving revolutionized book illustration. One of Anderson’s contributions to American art was his illustrations of American scenes and people in the children’s primers and tracts that were distributed across the nation. Unlike expensive metal engraving, images created from wood engravings could be reproduced cheaply and made accessible to children. Through his wood engravings, Anderson captured intricate details of the lives of the working poor, drawing on observations from his medical career to relay the depth of poverty many early American families suffered. The shading his wood engravings produced presented a nuanced depiction of subjects who lacked elegant dress or surroundings.

The frontispiece showcases sentimental props that heighten the appeal presented in the text. It depicts the domestic space of an impoverished family. The tiny garret’s slanted roof, dim lighting, cracked window, and sparse furniture visually depict the family’s poverty. A window with a missing pane is stuffed with rags to keep out the cold and clothes hang from a post to dry. Opposite the dying mother, Margaret sits on a box with a slumped posture, holding a book and reading to her mother. The mother’s face is turned toward the black girl. An excerpt from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard” is reprinted on the title page, a poem designed to persuade readers to acknowledge the desires of the poor for education instead of regarding their ambitions with “disdain.” In the novel, although benevolent white members of Margaret’s community step in to give her access to education, their assistance is futile. Although Margaret evolves from an uneducated beggar to a good, literate, Christian girl, this is not enough to save her. Despite her courage and determination to acquire an education, Margaret dies. Her efforts to become educated and adopt Christian moral values do not lead to resilience. Instead, as the frontispiece captures vividly, Margaret’s fortitude serves primarily to point to the need for white benevolence and the good works of the white community. Her suffering and premature death are designed to elicit in white readers a desire to aid the poor and the “degraded.”

The publication of The Tawny Girl in 1823 anticipated a cluster of antebellum children’s literature by antislavery white authors in which black girl characters functioned as protagonists who addressed slavery and racial inequality. The suffering, alienation, loneliness, and premature death of black girls in this literature are designed to evoke empathy in young readers and deliver an antislavery message. Widely circulated early American children’s texts that feature black girls include Poems: Moral and Religious, for Children and Youth (1821); and Blessings in Disguise; or, Pictures of Some of Miss Haydon’s Girls, by Caroline Chesebro. The Little Keepsake; or Easy Lessons in Words of One Syllable (1825) contains four brief chapters that teach lessons to children using racial themes. “The Swing” illustrates the separation of the races when a group of white children who “have just come out of school” are playing on a swing while a group of black children, two boys and a black girl, lurk behind a tree and “wait for their turn to swing.” The author tells readers: “Soon our white young friends will go home, and then these will take their turn.” The isolation of black children at school and at play is illustrated further by their labeling as “these” in this text, perhaps teaching young white readers less about tolerance and more about the hierarchical systems in place that separated the races.

A signature feature in early American children’s literature that features black girls is what I call interracial “play dates” in which a black girl and a white girl play together as an illustration of racial harmony. The term “play date” is intentionally unsettling because it is anachronistic. A “play date” is a twentieth- and twenty-first-century activity commonly associated with innocence, yet these scenes of play in the nineteenth century evoke inequality, racial disharmony, danger, and conflict. The frontispiece image of an early issue of Slave’s Friend (1837), an abolitionist periodical for children, features an illustration titled “Emma” that shows a white girl teaching a black girl how to read as a dog sits nearby. The characters’ hierarchical arrangement in the picture suggests imbalance. Emma, the white girl, is the tallest, most visible figure and is fully clothed. Grace sits in a crouching position under Emma’s arm and has bare feet. The triangulation of a black girl, a white girl, and a dog might reinforce a sentimental scene of goodwill, togetherness, and acceptance, yet Grace’s visually unequal position under Emma’s arm conveys how her presence serves simply to support white benevolence.

The story “Emma,” published in The Slave’s Friend, features “a neat little colored girl who used to come to the house of Emma’s father every Saturday afternoon to see her mother[,] who lived with the family. Her name was Grace.” Grace and Emma “used to play together; and sometimes they would work in the garden or sit down to read. Grace could tell her all the letters, A, B, C, and so on, but Emma wanted her to read without spelling, and so she would teach her, as you can see in the picture.” The author encourages its young readers to look carefully at the picture: “Just look at them. Isn’t it a pretty sight? How attentive Grace is. I dare say she loves to learn to read. Now do we see Emma, how animated and joyful she looks. She loves to be a little teacher, I guess. And how carefully they hold the book.” In this story, Grace is socialized through reading and learning with the aid of a white girl. The author’s repeated request that readers “look carefully” at the “pretty sight” of Emma and Grace reading together suggests that the interracial pairing is instructive. In a similar way, The Tawny Girl’s frontispiece sought to attract early American readers with a rare display of a black girl reading to a white woman. In both of these illustrations, the pairing of literate black girls with white female figures supports the values of racial harmony, gratitude, and ideal households that all whites should aspire to.

Specific publishing houses were invested in publishing children’s literature texts that featured black children. The American Tract Society, located in Boston, Massachusetts, published many antislavery titles and had an active publication program for children that competed with the literature of secular publishers. Songs for My Children: With Memoirs with Numerous Illustrations (1861), a popular publication by a white author, contained songs, rhymes and miscellany for child readers such as “An Example to Children,” “Aspirations,” “Haste to School,” “Calling Names,” Deeds of Kindness,” and “Don’t Fret.” “The Little Black Girl” features a black girl named Susie who laments her loneliness when her mother, Chloe, must leave home daily to work as a domestic. Susie looks in a mirror and connects her loneliness with the color of her skin: “Susie to their tiny mirror, / Climbing, saw her ebon face; / But she hid it with her fingers, / As if ’t were some deep disgrace.”

“Oh why was it,” sadly murmuring,

Susie asked herself aloud,

“When God made white children’s faces,

Over mine he spread a cloud?”

“No one loves me; naughty children

Laugh when e’er I go along;

And rude boys are always singing

In my ear some negro song.

I don’t love to sit at school,

With the children white and fair;

For it makes my face look blacker,

And more crisp my woolly hair.

Scrub and comb! And comb and scrub! I’ve

Tried to grow white many a day,

But my poor face still is colored,

And my hair will knot this way!

The lines suggest that black skin is shameful and that black children understand that they are inferior because of it, a sentiment that conveys the racism of supposedly benevolent whites. This poem was designed to elicit sympathy in white children for black children. However, young black readers might have read it as a message to wait for salvation through divine intervention instead of relying on themselves or hoping for changes in the nation’s legal system. When Chloe hears her daughter’s cries, she urges Susie to rely on God’s love to calm her worries: “Soon, my child, if we obey him, / We shall go to dwell above, / Where his own of every color/ Share alike a father’s love.” The image of Susie’s forlorn face captures the loss and loneliness of racial isolation. Similar to the frontispiece in The Tawny Girl, the portrayal of the young girl Susie looking in the mirror depicts the intersection of race, poverty, and sorrow.

In Lucy; or The Slave Girl of Kentucky, published by the American Reform Tract and Book Society (1858), an enslaved black girl argues vehemently against the horrors of slavery. The story opens with a white boy named Arthur who receives “no black marks” on his reports in school. As a reward, his aunt tells him a story. She tells him about a black girl named Lucy who she met during her travels to New Orleans as a young girl. The aunt traveled on a steamer headed to a slave market. The steamer stopped in Paducah, on the northwestern boundary of Kentucky, where she met a little slave girl named Lucy who was “about a dozen years old.” In dialect, Lucy explains to the aunt how she cried and screamed when she was sold and separated from her mother and grandmother: “You see dey wouldn’t nudder let me come wid mammy, nor take me back to granny, and so I couldn’t do nothin’ but scream.” Young Arthur learns about the plight of slaves, but he is relieved that he does not share their actual suffering: “I’ll pray that I may continue to hate the whole thing with all my might, and I’ll give thanks too, every day, that I was not born a colored child, to be sold away from all I love and to be taken down the Mississippi river.” The juxtaposition of the two sentimental scenes, in which an aunt tells a story to her nephew and an enslaved girl is separated from her family, serves to highlight the processes that contribute to a strong white family structure lest it be threatened by the influences of slavery.

Deborah C. De Rosa argues that white writers who delivered an antislavery message included representations of enslaved children primarily as a way to illustrate the impact of slavery’s atrocities on the innocence of white children: “Ironically, while these works oppose the slave child’s lost innocence and depict individuals interceding to prevent the child’s suffering, the domestic abolitionists nevertheless inflict lost innocence (through forced consciousness) onto the white child,” writes De Rosa. “While these white children do not literally free the slave children, their promises of prayers set the groundwork for change.” In Lucy; or The Slave Girl of Kentucky, the fact that a white child becomes aware of Lucy’s suffering seems to be more about his lost innocence than it is about that child cultivating empathy for Lucy. In the hands of white writers, black girls were as flat and two-dimensional as they were in the hands of black newspaper editors. Their function was to support a didactic lesson, and the focus was on the moral value of their external actions. White writers were not concerned with the inner lives of the black children they wrote about; the main concern of these writers was to persuade white children that slavery was evil so they could adopt the proper moral attitude in childhood and (it was to be hoped) take proper action against slavery in adulthood. In other words, the children white writers were concerned about were their own.

Further Reading

Caroline Chesebro, Blessings in Disguise; or, Pictures of Some of Miss Haydon’s Girls (New York, 1863).

Deborah DeRosa, Domestic Abolitionism and Juvenile Literature, 1830–1865 (Albany, N.Y., 2003).

John R. Edson, “Slave’s Friend,” in Children’s Periodicals of the United States: Historical Guides to the World’s Periodicals and Newspapers, Ed. R. Gordon Kelly, 408–411 (Westport, Conn., 1984).

“Emma,” Slave’s Friend 2:1 (1837): 2–4.

Jemmy and His Mother: A Tale for Children: and Lucy: or, The Slave Girl of Kentucky (Cincinnati, 1858).

Little Miss Consequence (Boston, 1880).

Little Rhymes for Little Readers (Boston, 1832).

Lynde Palmer, Helps over Hard Places: Stories for Girls (Boston, 1862).

Poems: Moral and Religious, for Children and Youth (Greenfield, Mass, 1821).

Jane R. Pomeroy, “Anderson’s Life and Introduction to His Work,” in Jane R. Pomeroy, Alexander Anderson: Wood Engraver & Illustrator: An Annotated Bibliography, vol. 1 (New Castle, Del., and Worcester, Mass., 2005).

“The Little Black Girl,” Songs for my Children: with numerous illustrations (Boston, 1861?).

The Little Keepsake; or Easy Lessons in Words of One Syllable (New Haven, Conn., 1825).

The Tawny Girl; or The History of Margaret Russel, Illustrating the Benefits of Education on the Most Degraded Classes of Society (New York, 1823).

Harry B. Weiss, Samuel Wood & Sons: Early New York Publisher of Children’s Books (New York, 1942).

William Sanders; or, Blessings in Disguise (Concord, Mass., 1848).

Nazera Sadiq Wright, “’Our Hope is in the Rising Generation’: Locating African American Children’s Literature in the “Children’s Department” of the Colored American” in Who Writes for Black Children? African American Children’s Literature before 1900. Eds. Katharine Capshaw and Anna Mae Duane (Minneapolis, 2017).

Nazera Sadiq Wright, “Maria W. Stewart’s ‘The First Stage of Life’: Black Girlhood in the Repository of Religion and Literature, and of Science and Art (1858-1861) in MELUS: The Society for the Study of the Multi-Ethnic Literature of the United States. 40:3 (Fall 2015): 150-175 Eds. Joycelyn Moody and Howard Rambsy.

Nazera Sadiq Wright, Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century (Urbana, Ill., 2016).

Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York, 2011).

Anna Mae Duane, Suffering Childhood in Early America: Violence, Race, and the Making of the Child Victim (Athens, Ga., 2010).

Katharine Capsaw and Anna Mae Duane, “Who Writes for Black Children?”: African American Children’s Literature Before 1900 (Minneapolis, 2017).

Brigitte Fielder, “Black Girls, White Girls, American Girls: Slavery and Racialized Perspectives in Abolitionist and Neoabolitionist Children’s Literature,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 36:2 (Fall 2017): 323-352.

This article originally appeared in issue 18.2 (Spring, 2018).

Dr. Nazera Sadiq Wright is associate professor of English at the University of Kentucky. She is author of Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth Century (2016). During 2017-2018, she is in residence at the Library Company of Philadelphia as a National Endowment for the Humanities Fellow and an Andrew W. Mellon Program in African American History Fellow to advance her second book.