Brothels for Gentlemen: Nineteenth-Century American Brothel Guides, Gentility, and Moral Reform

Nineteenth-century American brothel guides were the perfect size to be concealed in a gentleman’s pocket. They were about six inches tall and slender, usually containing no more than about forty pages in total. These paperbound booklets were valuable primers for men who wished to learn how to navigate urban underworlds of commercial sex. Brief reviews gave readers a sense of the general cost, quality, and clientele of each house, with an emphasis on houses that catered to white men of the middle, upper, and upwardly aspiring socioeconomic classes. American brothel guides focused primarily on brothels in New York City and Philadelphia, but also provided information about urban brothels across North America, as far north as Chicago and Montreal, as far south as Mobile and New Orleans, and as far west as Little Rock. This broad geographic scope suggests first a national network of informants, and second, that publishers intended these guides to be distributed, read, and used nationwide. Only eight American brothel guides, representing seven unique titles, survive in American archives. Published in New York and Philadelphia between 1839 and 1880, these texts comprise what is arguably the most important set of artifacts commemorating nineteenth-century urban prostitution in the United States.

These booklets reflect the influence of two print genres that were new to nineteenth-century American publishing: city directories and travel guides. Brothel guides’ lists of addresses and names recall city directories, which were published primarily for urban residents and provided the names and addresses of private individuals and local businesses. Brothel guides were also kin to American travel guidebooks for upper-class and upwardly mobile readers, which were first introduced in the 1820s. Ordinary travel guides focused on “fashionable” tours of the American countryside, leisure-time sojourns inspired by the British coming-of-age experience for well-to-do sons, the European “grand tour.” Brothel guides also served a purpose similar to that of urban travel guides, helping visitors find order and avoid unpleasant adventures in chaotic, rapidly growing, demographically heterogeneous cities. The audience for this literature was an emerging “fashionable” class of the educated, prosperous, status-conscious class that would later be known as the American bourgeoisie. A distinctive branch of the growing middle classes, the bourgeoisie was easily identified by its members’ conspicuous displays of wealth in the form of expensive commercial goods and mannered social rituals. Houses, furnishings, clothing, careful self-presentation, and social etiquette all served to signal bourgeois Americans’ prosperity and elite social status.

Reviews ranged from a few words to entire pages. Brothel guides’ covers were made of the same yellow paper that covered pornographic works. Thus, even before reading the title, a savvy man would know from the color of the cover that these pamphlets were full of erotic promise. The actual content of these guides had little in common with pornography, however. In fact, American brothel guides were surprisingly silent about the sexual activities that obviously went on in the bedrooms beyond brothel parlors. Further, the pages of these guides sustain what seems at first to be a peculiar focus on praising houses of prostitution that exemplified middle-class and bourgeois ideals of respectability, gentility, and good, class-conscious social order. For instance, the earliest known American brothel guide, Prostitution Exposed, published in New York City in 1839, declared that Mrs. Williams, at 21 Sullivan Street, ran a “very quiet and a genteel resort.” Similarly, Abby Mead’s house at 134 Duane Street, a fifteen-minute stroll to the southwest was, the guide promised, “decidedly A. No. 1, for respectability.”

Like a nineteenth-century Zagat’s for brothels, Prostitution Exposed appended reviews to its list of addresses and names, and later guides followed suit. The seven brothel guide titles that survive in archives today contain a total of 297 reviews, with 213 (72 percent) offering praise that highlights the gentility and respectability of these houses of prostitution and the women who worked in them. Sixty-five of the 213 positive brothel descriptions (about 30 percent of the total) used the terms “quiet,” “orderly,” “private,” “genteel,” and/or “respectable” to describe the merits of various houses. Most other positive reviews made similar, class-based judgments using similar language. They reflected middle-class social values in their promises, for instance, that a house was “free from vulgarity,” possessed a “good reputation,” or treated men with respect and decorum. In 1839, the fine house run by Julia Brown was noted for its unsurpassed “good order,” a direct rebuttal to the judgment implicit in the nineteenth-century legal term for a brothel, a “disorderly house.” As I will discuss shortly, prostitutes and brothel keepers (in first-class houses, exclusively women until at least mid-century) were also praised for their good breeding, “agreeable” temperaments, and well-mannered behavior.

Historians have offered various explanations for the curious emphasis on gentility and respectability in these guides and the absence of explicitly sexual language. The tone and content of American brothel guides, especially when compared with the bawdiness of English ones, led historian Timothy J. Gilfoyle to call them “priggishly American: pragmatic, straightforward, empirical, and objective.” Other historians have regarded this apparent priggishness as a thinly veiled mockery of urban moral reformers and a critique of middle-class men’s hypocrisy. American brothel guides’ constant reassurances about gentility can certainly be read this way, and they may even represent an effort to camouflage the true purpose of these guides. My study offers additional ways of reading this evidence: as authors’ anticipation that their readers were class-conscious men who would be concerned about the dangers involved in brothel-going, about the possibility of social discomfort in these unfamiliar settings, and about whether they could visit brothels without compromising their own sense of themselves as respectable gentlemen.

Both negative and positive assessments of urban brothels helped authors define for readers the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion within an imagined community of gentleman brothel-goers. As Philip Howell has suggested, the very act of reading brothel guides helped readers imagine themselves as part of an exclusive brotherhood of men linked by their privileged knowledge of forbidden information. Critiques of brothels that catered to poor and working-class white men or black men of any class provided a further measure by which to demonstrate the superiority of white men who attended the better kind. As yet, no scholar has taken seriously the significance of these guides for providing middle-class and bourgeois men with an entirely new way of thinking about brothels, prostitutes, and even themselves. In American brothel guides’ admiring descriptions of first-class brothels, ladylike prostitutes, and the refined gentlemen who visited them, authors refuted moral reformers’ bleak view of prostitution and men’s role in perpetuating it.

Throughout the nineteenth century, middle-class, evangelical Christian moral-reform activists worked fervently to eradicate prostitution. While such efforts began in the late eighteenth century, moral reform organizations grew at an accelerated pace beginning in the 1830s. As American cities began to grow rapidly in this period, prostitution flourished in tandem. Reformers responded with a variety of strategies: evangelizing, rescuing prostitutes who wanted to get out of the business, and warning Americans through spoken word and print about the many dangers that prostitution posed to individuals, families, and even the very social fabric of the United States. The movement expanded into an effort to suppress all forms of non-marital sexuality, including masturbation, and reformers’ collective voice dominated nineteenth-century discourses about sexual matters. Moral reformers quickly became the dominant force in shaping popular ideas about human sexuality, advocating the repression of all sexual activity except within the sanctity of marriage. They stressed the new idea that prostitutes were victims of both economic circumstance and men’s failure to control their own sexual impulses. They called upon middle-class women to exert their domestic power and shun such men from social gatherings.

In the cheeky guise of moral reformers, the authorial personas of two nineteenth-century American brothel guides responded by providing justifications for brothels and brothel-going. Disguising their bold stance with the sheep’s clothing of moral reform rhetoric, these authors argued that efforts to end prostitution were futile, and that, in fact, prostitutes’ sexual services were beneficial and even necessary to maintaining a well-ordered society. Prostitution Exposed openly mocks moral reformers, beginning with its subtitle, “A Moral Reform Directory.” Upon opening the little guide, however, the ruse is clear: the frontispiece illustration of the booklet, facing the title page, is a roughly carved depiction of a nude, long-haired courtesan. With wicked, deadpan humor, the following dedication page extends the masquerade when it honors “the ‘Ladies’ Reform Association’ for the Suppression of Onanism.” The name of the organization appears at first little different from the names of actual moral reform societies. A closer reading, however, makes it clear that the title refers instead to prostitutes who provide sexual services, thus “saving” men from having to satisfy their sexual needs through “onanism,” another name for masturbation.

In the introduction that follows, the author employs the educated and certain tone of a gentleman reformer to justify his guide as merely designed to help godly, respectable men avoid the houses listed in the subsequent pages. Still, the author addresses “the reflecting reader,” calling on him to help “to crash the hydra-headed monster” by visiting these houses of prostitution. “Go you, personally,” he exhorts, “and with gentle admonitions, endeavor to prevent those midnight debaucheries, those base and disgraceful acts of bodily prostitution, which destroy thousands yearly through their baneful effects.” In a mocking of male moral reformers like John C. McDowell, who visited New York City brothels in the 1830s to rescue prostitutes, the author notes, with subtle satire, that prostitution continues to thrive in spite of men’s meetings with prostitutes to “commune with them in private.” “Commune,” of course, bears the double meaning of both a meeting and a sexual encounter, allowing readers to bring their own sexual knowledge and understanding to deciphering the author’s meaning.

The author of Prostitution Exposed goes on to argue that brothels are necessary to guard the safety of chaste and respectable women. This argument helps preserve the nineteenth-century middle-class womanly ideal, which rendered “true” women as pious and sexually pure. Although prostitution kept sex workers imprisoned as “lewd and wretched victims” of male passion and vice, their services were, the author argues, “a guard to virtue.” Employing the hoary myth that rape was the inevitable result of men’s repressed sexual passion, he explained that prostitution made it “less likely” that “respectable females” would “have the sanctuary of their virtue encroached on by lustful, amorous man.” Without commercial sex, “the bridegroom would seldom fold to his bosom a virgin, for the blight of illicit intercourse would disfigure the holy shrine of wedlock.” The author of Guide to the Harems and Turkish Palaces of the Empire City (1855, 1856) concluded likewise that brothels were “the best safe guards to the virtue of maidens, wives, and widows, who would otherwise be exposed to violence and outrage.” From this vantage point, gentlemen who visited well-mannered young ladies in “well conducted” brothels upheld, rather than compromised, the sanctity and respectability of the middle-class family. In mock sympathy with moral reformers, the author of Guide to the Harems concludes that all efforts to eradicate prostitution were ultimately futile. Regardless of reformers’ “preaching and moralizing,” he writes, men would “continue to seek amative intercourse with the opposite sex.”

Both authors rested their arguments on an assumption that prostitutes were of a breed entirely apart from “virtuous” women. Yet, in the rest of each guide, as in the pages of other nineteenth-century American brothel guides, descriptions of genteel brothel keepers and prostitutes suggested that they were little different from the ideal women of respectable, class-conscious society. Among the middle and upper classes, a woman’s reputation for chastity and her dependence upon men were foundational to her social identity. Conversely, a prostitute’s sexual and financial independence defined her as a permanent outsider. While the existence of prostitution supported the ideology of “true” womanhood by freeing wives from husbands’ sexual demands, the outsider women who met those sexual demands were paradoxically portrayed in brothel guides as just as respectable. Brothel guide authors erased the division for readers by judging prostitutes and brothels according only to the quality of their performances of middle- and upper-class feminine ideals. Brothel guide authors praised genteel brothels and their women using terminology that could just as easily have described more ordinary households and the respectable wives and daughters within them. For instance, the women who worked for Jane McCord in 1859 were noted to be well versed in “the rules of etiquette, &c., of society.” Miss Parker’s “beautiful and accomplished boarders” captured visitors’ attention “with their bewitching smiles and graceful manners.” Madame Louisa Kanth’s “pretty boarders” were all “supremely mannered,” and her house “a safe and honorable retreat.” In 1849 Philadelphia, the brothel keeper Mary Fisher reportedly “conduct[ed] herself with propriety,” and in 1855 New York, a brothel keeper who called herself “Madame A. Belle” reportedly had been “educated in the best circles.” Selfless attention to others, charm, and gracious hospitality were key components in these performances of the respectable womanly ideal, and the charming and attentive prostitute was, at least outside the brothel bedroom, an imitation of her respectable counterparts in family homes.

Even though brothels were antithetical to middle-class values, brothel guides’ emphasis on the similarity between genteel prostitutes and respectable women allowed men to have it both ways. Keeping company with well-mannered women in houses of prostitution that were almost—but not quite—respectable domestic spaces may have helped men justify brothel-going by blurring the line between the domestic and the commercial, the genteel and the illicit. While moral reform literature generally emphasized the wide gulf between prostitutes and their middle-class, respectable counterparts, brothel guides tried to close this gap. Such descriptions also provided another measure by which class- and reputation-conscious gentlemen could judge and define themselves and other men.

Brothel guides’ reassurances and warnings about the relative safety or danger of various houses expresses authors’ anticipation of bourgeois readers’ concerns. Authors promised to provide reliable information that would prevent genteel readers from stepping into “the traps which are everywhere laid” by criminals who preyed on naïve men. A woman who solicited sex on the street, no matter how respectable her appearance, might actually be a pickpocket, or part of a panel scheme, with an accomplice hidden in a secret compartment behind bedroom paneling, waiting to sneak into the room and steal a man’s valuables. Matthew Hale Smith described this scheme in his sensational 1868 exposé of urban underworlds, Sunshine and Shadow in New York: “The place selected is usually a basement in a quiet neighborhood, the more respectable the better … The room is papered and a panel cut in the paper, or one of the panels is fitted to slide softly … The bolts, and bars, and locks are peculiar, and so made as to seem to lock on the inside, though they … really fasten on the outside. And while the visitor imagines he has locked all covers out, he is really locked in himself, and cannot escape till he has been robbed.”

Blackmail was another concern for reputation-conscious men. The Gentleman’s Companion warned in 1870 that a man who was married or one “well known to the public” was vulnerable to blackmail. Devious female “plunderers” operated under “the presumption . . . that fear of exposure will prevent him from making a complaint” against them. The author of the Philadelphia Guide to the Stranger warned in 1849 that both “the stranger and the green one” were at particular risk of being “deluded into houses of bad repute without being aware of the impending danger.” The author of the Fast Man’s Directory (1853) warned readers to avoid an earlier (and competing) New York City brothel guide, which, he said, would lead readers to houses in which they would “run a great risk of being robbed, diseased, and perhaps ruined for life.” That ruin could be social, physical, financial, or all three.

With one exception, most nineteenth-century American brothel guides said little or nothing about the dangers of disease. Some gestured vaguely toward the issue with general terms like “safety” and “danger.” For instance, the 1839 guide, Prostitution Exposed, included a note assuring readers that the women at Sal Brown’s house were “clean and safe.” An entry in the New York City Gentleman’s Companion noted that Mrs. Lizzie Goodrich kept a physician “attached” to her house, suggesting that the women who worked there received regular checkups and treatment. The only American brothel guide that addressed the question of venereal diseases directly was Guide to the Harems. Its author, an “Old Man of Twenty-five,” promised that his little book would “prevent many a man from falling into a wicked snare,—warn others of the traps which are everywhere laid for him,—secure thousands from the chances of disease and ruin, and give all to understand where they can go with more safety.” The guide was “a source of kindly warnings, in regard to places of vice and danger,” even an altruistic “act of humanity” designed to warn urban visitors about the “hidden rocks upon which many a noble vessel has been shipwrecked.” In other American guides, readers were left to infer that the young, enchanting, well-mannered “ladies” employed in genteel brothels were, like respectable wives and daughters, clean and free from disease. The correlation between outward appearances and prostitutes’ health rested, of course, on the erroneous idea that disease was always visually detectable, and that gentlemen customers carried no diseases themselves.

Assurances of safety also anticipated other forms of danger that might lurk within an unfamiliar brothel. Violence was an inescapable part of men’s social worlds in the nineteenth-century United States, and brothel guides hinted at the fact that violence at the hands of other men, including visitors to first-class houses, was always possible. Notions of manhood required that blood be shed, from the Founding Fathers’ penchant for honor-defending duels to the street-prowling roughs of New York’s antebellum Bowery. That masculine culture of violence sometimes extended into brothel parlors, where men gathered to drink and socialize with brothel keepers, prostitutes, and each other. In the 1830s, New York City saw a surge of violence against brothel keepers, prostitutes, and their property, and although attacks on brothels appear to have largely died down by the end of the decade, spontaneous acts of violence remained a possibility.

There were relatively few negative reviews in brothel guides; they speak of the potential for both danger and social discomfort that awaited a gentleman who chose the wrong kind of house. Authors warned of houses that admitted white, working-class men and black men of any class, demonstrating the pervasiveness of ideas about the inferiority of blacks and untamed whites. For instance, in 1870, Hattie Taylor’s third-class New York City house was reportedly visited by “gentlemen who turn their shirts wrong side out when the other side is dirty.” Clearly, “gentlemen” is used here ironically. What was to one man a resourceful strategy of self-presentation was to brothel-guide authors (and, presumably, readers) evidence of a brutish character, signs of an instigator of disorder and carrier of disease. In the 1859 Guide to the Seraglios, the assertion that Sal Boyer (alias, Dutch Sal) had sex with a black man of the “lowest” sort highlights notions of white gentlemen’s class-based, racial superiority. According to the author, even worse was the alleged purpose of this interracial liaison: an exchange of sexual services “for the small remuneration of potatoes and flour to support her boarders.” This crude, non-monetary exchange of sex for such basic sustenance was a further indicator of the woman’s base character. In American brothel guides, working-class whites and black men represented a level of brutishness that contrasted starkly with white gentility.

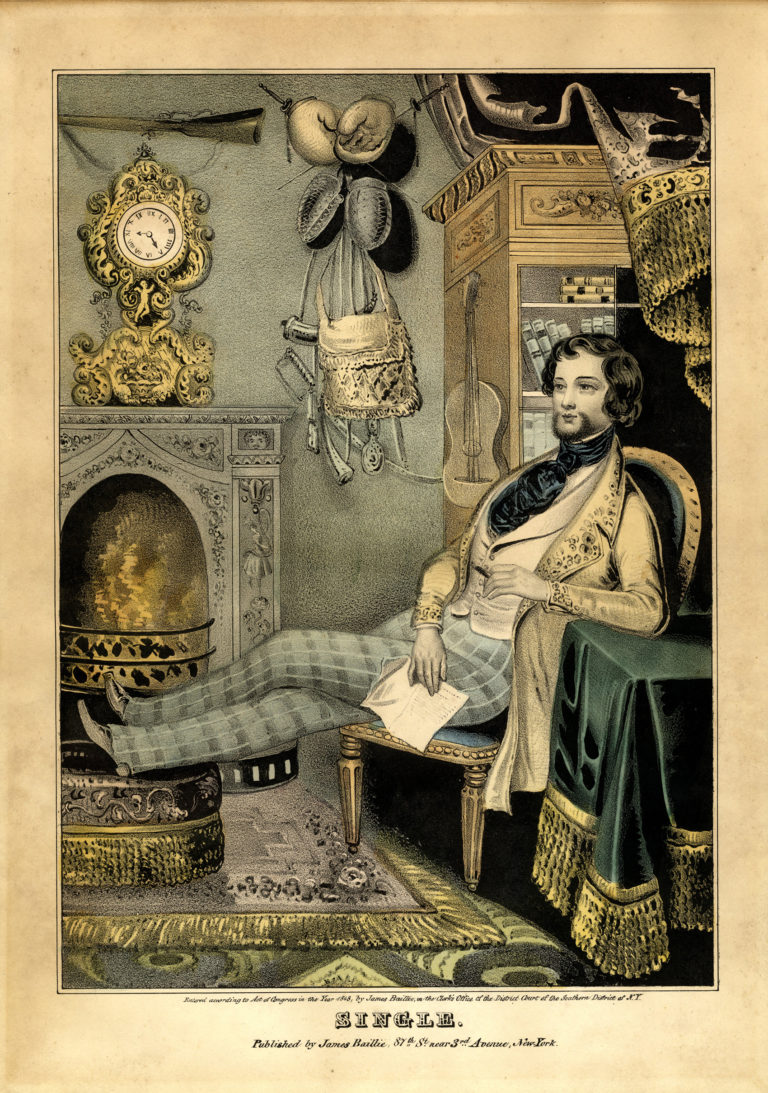

Conversely, many brothel guide reviews emphasized that the best houses were visited by gentlemen. In a circular set of associations, the presence of gentlemen signified the quality of a house and its women, which served in turn to signify the status of the men who visited. Such claims also signaled to class-conscious readers that they could visit these houses without compromising their sense of themselves as gentlemen. The very title of the Gentleman’s Companion sought to flatter the reader, and suggested that the men who attended the brothels recommended in its pages would encounter in those places only men of similar respectability. Brothel guide entries often described brothel visitors as “gentlemen” or “gents” to highlight the quality of certain houses. Readers were assured, for example, that the house at 99 Mercer Street in New York was “frequented by men of taste.” The Philadelphia Guide to the Stranger noted in 1849 that at Sarah Turner’s house “none but gentlemen” visited “this Paradise of Love.” The brothel run by Miss R. Stiles was called one of the finest in 1853 New York. This splendid house was “of the very first class,” and the fact that it was reportedly attended by “none but gentlemen of distinguished rank, education, and conduct” affirmed its quality. The 1848 print by James Baillie, “Single,” imagines this young, well-educated, bourgeois “gent.” He sits in calm, dignified, manly repose, surrounded by the trappings of genteel, prosperous manhood within his well-ordered and fashionable domestic space. While twenty-first-century viewers might see the subject of this image as feminine and effete, the fashionable, tight-fitting clothing and his elegant bearing are typical of the pre-Civil War manly ideal as portrayed in popular American prints. In this aspirational image, the single gentleman is defined by an array of commercial goods. The fine, fashionable furniture and mantelpiece, the ornate ormolu clock, the thick, heavy drapes, carpet, and upholstery all signify financial prosperity and bourgeois taste. Rows of leather-bound books speak of the gentleman’s education, and both the roaring fire and the time on the clock—8:25 in the evening—suggest that this gentleman is at the end of a long day of gentlemanly pursuits. The boxing gloves and fencing foils hung on the wall represent the leisure-time arts of English aristocrats, and the hunting gear, including an indigenous-style, western leather bag, suggests the manly touch of the rugged American frontiersman. The authorial persona of each surviving nineteenth-century American brothel guide represents just such a figure: a confident white man of privilege, one of the fashionable, knowing, unmarried “young bucks” for whom brothel visiting was a weekly, if not daily, pastime.

Given the dominance of the moral reform perspective in nineteenth-century understandings of prostitution, the very idea that a brothel could be genteel appears to pose a deep contradiction. According to middle-class moral reformers, prostitution was, by its very nature, the antithesis of respectability. By extension, brothels were antithetical to the nineteenth-century domestic sphere, and prostitutes were entirely unlike respectable women. While brothel guide authors did mock moral reformers, they had an earnest message: that prostitution could be compatible with middle-class, bourgeois, and even upper-class white manhood. Contrary to moral reformers’ excoriation of men who visited brothels, the guides’ positive descriptions of well-behaved, mannered, self-conscious brothelgoers suggested that if such genteel, respectable men allowed themselves to enjoy the sexual pleasures for sale in American cities, then why couldn’t the reader himself? This emphasis on gentility also helped clarify for readers the kind of man who would be welcome at the better urban brothels, just as negative descriptions of other types of men helped clarify who would be unwelcome. Implicit in these guides is an argument in favor of men’s sexual pleasure-seeking that turns on the notion that a gentleman’s self-respect and dignity did not rest in his sexual behaviors, but in his continuous self-presentation as a gentleman and in the company that he kept. In this way, brothel reviews reiterated and reinforced the notion that there was really nothing wrong with visiting brothels, engaging in casual sex with professional prostitutes, and paying for these privileges, as long as men—white, class-conscious men—were careful to attend the right kinds of houses. The “right” kinds, of course, were those touted in the guides.

Acknowledgments

My deep thanks to Carolyn Eastman, Catherine A. Jones, Frances M. Clarke, and Michael Henderson, all of whom offered invaluable feedback on drafts of this essay; to Anna Mae Duane for her astute editing; and to Jaclyn Penny at the American Antiquarian Society for her always insightful and expert assistance with images.

Further Reading

Patricia Cline Cohen, The Murder of Helen Jewett: The Life and Death of a Prostitute in Nineteenth-Century New York (New York, 1998).

Donna Dennis, Licentious Gotham: Erotic Publishing and Its Prosecution in Nineteenth-Century New York (Cambridge, Mass., 2009).

Richard Gassan, “The First American Tourist Guidebooks: Authorship and Print Culture of the 1820s.” Book History 8 (2005): 51-74.

Timothy J. Gilfoyle, City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex, 1790-1920 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1992).

Marilynn Wood Hill, Their Sisters’ Keepers: Prostitution in New York City, 1830-1870 (Berkeley, 1993).

Barbara Meil Hobson, Uneasy Virtue: The Politics of Prostitution and the American Reform Tradition (New York, 1987).

Helen Horowitz, Rereading Sex: Battles over Sexual Knowledge and Suppression in Nineteenth-Century America (New York, 2002).

Philip M.R. Howell, “Sex and the City of Bachelors: Popular Masculinity and Public Space in Nineteenth-Century England and America.” Ecumene 8:1 (2001): 20-50.

This article originally appeared in issue 18.1 (Winter, 2018).

Katherine Hijar is an assistant professor of history at California State University, San Marcos.