Building Baltimore in Black and White

Seth Rockman’s Scraping By sets out to tell “the story of the chronically impoverished, often unfree, and generally unequal Americans whose work made the United States arguably the most wealthy, free, and egalitarian society in the Western world” (3). The scene is the scrappy, fast-growing, border city of Baltimore between the 1790s and the 1840s. Rockman’s subjects are those workers—male and female, black and white—who labored outside of the formal structures of early capitalist development that have been so thoroughly documented elsewhere. But Rockman does more than simply tell the story of those left out of the period’s rapidly expanding industries and economic success stories. Rather, he shows that these men and women were “the very foundation of capitalism in the early republic” (8). Their work—dredging Baltimore’s harbor on the ingenious mudmachine, scraping muck from the streets, building bridges—was the indispensable foundation (sometimes literally, in the case of bridge-building, for example) for the economic development of Baltimore specifically and the republic generally.

Departing from earlier scholars’ emphasis on artisans and the decline of craft labor, Rockman turns his attention to Baltimore’s unskilled laborers, those men and women who never achieved economic success and never climbed from manual labor to landed prosperity. But Rockman convincingly argues that these laborers formed the backbone of the early republic’s economic advances; they did not benefit from Baltimore’s boom, but it could not have happened without them.

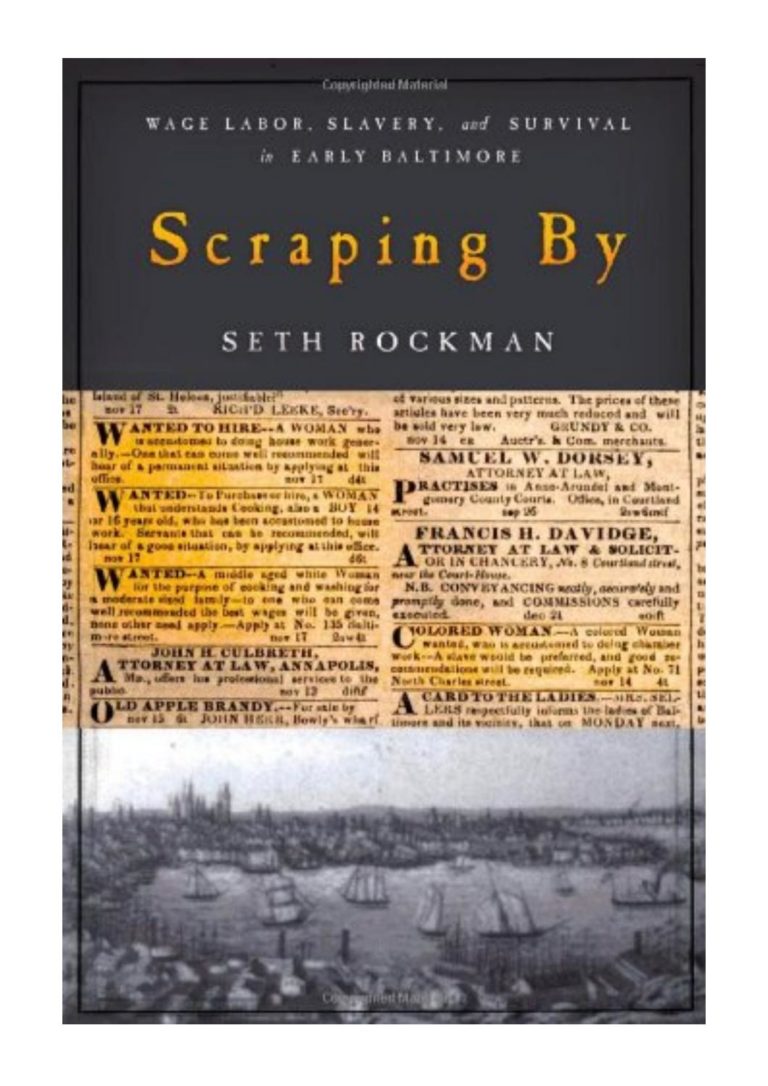

Scraping By begins with demography. Who worked in Baltimore? “Those who [had] no choice” (12), Rockman tells us. Baltimore grew into America’s third-largest city in these years, and that growth was fueled by runaway slaves and white men driven to the city by changes in rural agriculture as much as by immigration from abroad. Once such men and women arrived, getting a job required parsing local mores about job advertisements, hiring, and racial and ethnic codes around labor. Rockman picks apart those unwritten codes in a chapter focused on five men: a white workingman, a slave, his owner, a free African American, and the man who hired their labor for work at a construction site. The intersections of their lives at Jones Falls illustrates the possible paths to job procurement, as well as the motives of the bridge contractor who chose this mix of free and unfree labor.

Rockman next turns to the men who worked dredging Baltimore’s harbor, making possible the commerce that was the city’s lifeblood. Analysis of payrolls for the mudmachine that kept the channel clear gives a window into men’s movement onto and off of the digging crew. These records suggest that for most mudmachinists, “manual labor was not a life stage to be outgrown, but a career” (99).

A career in manual labor, however, was likely to be made up of numerous short-term jobs, for women as well as for men. Rockman takes up women’s stories in two additional chapters, treating laundresses, domestic workers, and seamstresses in turn. Here, too, slavery and free labor were intertwined. There were few jobs available for women, but the bigger problem for most was that “custom placed other impediments in the way of women’s economic self-sufficiency” (131). The persistence of slavery meant that “purchasers of female labor were frequently the purchasers of female bodies” (131). The assumption that free women resided in male-headed households meant that they were never paid wages sufficient for self-support. Women’s presumed dependence on men led, when male aid was absent or insufficient, to dependence on the state. The idea that much of women’s domestic work was invisible and poorly or unremunerated is not new, but Rockman shows that the assumption of female dependence made women illegitimate as economic actors, and that carefully constructed gendered scripts characterized both their appeals for aid and the responses of wealthier Baltimoreans. In these chapters, too, Rockman teases out the ways that gender both intersected with race and independently shaped the lives of the working poor. A later chapter extends this analysis by examining families, and the internal economies of various sorts of family and non-family households.

When Baltimore’s working men and women failed to find work, they drew on (or were thrust into) various charitable enterprises, and the Baltimore almshouse serves as Rockman’s case study. Built in the early 1820s, the almshouse served a variety of purposes. For the elites who funded it, it was both a “performance of Christian duty” (198) and, through stringent regulations applied to both inmates and applicants, a way of “maintaining the social stability that facilitated their prosperity” (218). Yet, Rockman claims, “the almshouse belonged … to Baltimore’s poor” (198), who used it for their own ends. Some spent winters there; others institutionalized their children. Still others used the institution’s hospital, finding refuge in the almshouse long enough to recover from injury or an alcoholic bender.

Perhaps Rockman’s most surprising finding is that Baltimore’s work sites were not strictly segregated by race, or even marked by stringent separation of slave from free laborers. Instead, he shows, employers often hired both free men, white and black, and slaves for the same projects. Yet, these same employers were not blind to race and status, sometimes specifying racial preferences clearly in their advertisements. Even at mixed-race job sites, employers had specific reasons for each hire, balancing, for instance, the capital investment in a slave with the risk of a free white man’s walking off the job. The intersections of race, gender, and labor were, Rockman shows, “unpredictable and inconsistent,” but not random (68).

A similar balancing act, between capital investments and the desire to get as much work as possible out of an individual at every moment, led to the development of prospective manumission, in which owners promised to free a slave at some future date if certain conditions—an agreed purchase price, faithful labor in the interim—were met. Rockman finds that “an entire secondary market appeared” in Baltimore for these term-slaves (60). A buyer of a female term-slave could look forward to not only her labor during the remainder of her term, but also the labor of any children she bore, since they would remain slaves for life.

While the development of such prospective manumission arrangements contributed to the growth of Baltimore’s free African American population (Rockman reminds us that 60 percent of the city’s black population was free in 1820), such schemes also kept African Americans in poverty. When the price of a family member’s freedom was added to the household expenses of a family already barely eking out a living on Baltimore’s margins, it was no wonder that black Baltimoreans failed to acquire capital or join the ranks of skilled artisan labor. By promising freedom at some specified, but distant, date, owners shifted the incentives that shaped the work of their enslaved laborers, and further immiserated their free relatives.

The book relies on exceptional work with a variety of primary sources. Since washerwomen and mudmachine workers left no letters or diaries and formed few records-producing organizations, Rockman has instead painstakingly pieced together clues from state and municipal records, particularly those of the Baltimore almshouse and the courts, and from newspapers. Although the limitations of this source base mean thatScraping By can tell only fragments of any individual’s story, Rockman weaves these bits and pieces together, if not into narrative—there is little change over time here—then into a cogent whole. The writing is clear and the argument compelling throughout.

Rockman began work on Scraping By well before the current economic downturn, yet the recent record-breaking rates of un- and under-employment make this analysis of American capitalism’s development all the more timely. Rockman’s skillful work, however, seems likely to long outlast this stage of the business cycle; indeed, by showing the deeply interconnected nature of free and slave labor for both men and women, Scraping By establishes a new starting point for further work on the labor history of the early republic. All historians of the era, as well as economic historians of every era, will want to read this fine book.

This article originally appeared in issue 10.3 (April, 2010).

Lynda Yankaskas is a Collateral Assistant Professor of History at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her book manuscript in progress is entitled “Borrowing Culture: Social Libraries and American Civic Life, 1731-1854.”