Cabin Fever in Frontier House

Let me be candid. I couldn’t stand watching Frontier House, the recent PBS series that chronicles the attempts of three families to survive five months of 1880s-style homesteading in Montana. Heavily edited, overly emotional, the show seemed to pander to the basest elements of reality TV. And it was hard to take its “reality” seriously when it began with ads (yes, even on PBS) like this Madison Avenue gem: “Life on the frontier would have been different with GP brands like Quilted Northern Bath Tissue.”

The show attempts to recreate the experience of families who moved to the American frontier in the late nineteenth century to stake a claim on 160 acres of land in Montana. The three families who volunteered for this experiment agreed to give up modern conveniences and to spend several months, from early spring to early fall, building cabins, cooking on wood stoves, milking cows and trading at Hop Sin Yin’s 1880s-style general store. The goal for the summer months was to lay in enough supplies and create a sound enough plan to convince a panel of independent historians and experts in domestic life, animal husbandry, and historic buildings that they would successfully survive the Montana winter. Nate and Karen Brooks are a young East Coast couple who married on camera (Nate’s father Rudy started the project, but left after the wedding), Adrienne and Gordon Clune head a well-to-do California family. They came with their three children and teenaged niece. Karen and Mark Glenn from Tennessee homesteaded with Karen’s two children. As the series began, we met each of these families in turn and watched them start to negotiate their familial and neighborly relations.

The going was rarely smooth. Early on, the scandal broke: Meatgate. The Clune family, those nefarious neighbors, those moonshining malcontents, reviled for whinin’ and wranglin’ and all around wickedness, had crossed the lines, left their homestead, and traded baked goods for venison, exotic out-of-season potatoes, and a few minutes of MTV. Their fellow frontiersmen and women reacted badly. They were shocked, shocked to find that there were historically inauthentic activities going on, or so they told their camera crew.

But what is authentic about Frontier House? Homesteader Karen Glenn figured her approach to this experiment was the real deal, contrasting her honest work as a laundress to the offsite trading of the Clunes: “We have done everything authentic.” The concept was bandied about on the show, used by the folkway experts who tutored the neohomesteaders on everything from chopping wood to birth control and by the families before, during, and after their tenure in Montana, but none of the characters seemed to find a universally satisfying definition. What was authentic about the on-air wedding of Kristen McLeod and Nate Brooks? The maroon and pink wedding dress, a perfect replica of 1880s finery that was such a disappointment to the bride, or her happiness when she saw the white gown sent by her fiancé? What was more authentic, the beans-and-cornmeal diet the characters enjoyed, or the wild game that Gordon Clune wanted so desperately to hunt with his sons? (He had to wait until his return to California, where he and his sons gunned down “Malibu rabbit” for their freezer.) Why this quest for authenticity? Why this judgment about whether or not the participants really lived the life of 1883 homesteaders? Is the experiment a success if they feel as though they were homesteading or only if they convince the experts that they’d worked hard enough to survive the winter?

These questions are similar to those posed to advocates of living history museums. They dog any effort to institutionalize what historians Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen call “popular historymaking,” the ways that “Americans take an active role in using and understanding the past” so that “they’re not just passive consumers of histories constructed by others.” Rather, we seize on aspects of the past that get under the skin, seem pertinent, even instrumental to our own lives.

But the dangers of the living-history approach are obvious. Do television producers (or museums) ignore the issues or situations that wouldn’t attract or might even offend viewers? Frontier House spends a lot of time dealing with personal hygiene issues (love that slow pan of the inside of an outhouse), but largely ignores the incredible racism and hardship that African Americans faced on the frontier. Although the narration talks about the problems a mixed-race couple such as the Brooks would face “back east,” it suggests that homesteaders might have found safer spaces in Montana. But Frontier House is set in 1883, the same year that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional, thus legalizing racial discrimination in the shops, inns, and other places that serviced (or refused to service) western settlers. We get only a glimpse of race prejudice in the brief discussion of whether the community is willing to pay for its own school, where future Brooks children would be welcome, or whether the two white families would rather save their money and exclude them. (There really isn’t any “discussion”—the community easily and immediately does the right thing.)

Living history museums have struggled with problems of representing these most difficult elements of the U.S. past to their patrons—witness the recent inclusion of slaves’ experiences at Colonial Williamsburg. By contrast, Frontier House participants worked without benefit of the academic and professional debates that have helped museum directors and docents introduce issues of slavery, racism, and genocide—and of course, Frontier House participants weren’t in character. They were doing what countless press releases called “hands-on history.” We certainly wouldn’t have wanted to view scenes of, say, wife beating, no matter how authentic domestic violence was for an isolated, stressed frontier family.

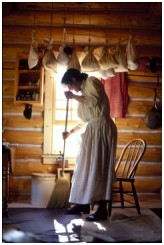

Which brings me back to the element of the series I find most valuable. It was telling in the last episode, when the homesteaders were making ready to leave, that each male “head of the homestead” expressed regret—with tears—at leaving. The men felt a sense of ownership, of pride at what they had accomplished. But the adult women were ready to go. All three at some time or other had talked about their unhappiness in this experience. Adrienne Clune compared her life in Montana to a “labor camp” and felt as though her departure meant “freedom, freedom, freedom.” Kristen Brooks stood in front of her kitchen area and noted that whenever the camera crew showed up, she could be found in that space, working as “support” for her man, and when Karen Glenn and her husband were struggling in their relationship, she talked about the frustration of having no way out.

In each of the families, the adult couples had accepted and occupied conventional gender roles, seemingly with no debate. Working outside, the men had lost weight, gained muscle, and laid in memories that would become touchstones in their later lives. The women, tied mostly to their cabins, felt ugly, frustrated, and exhausted by menial, repetitive drudgery. Now this reaction was authentic. Caroline Kirkland described the lot of such women in her 1839 book A New Home, Who’ll Follow?, a memoir of her own experiences in frontier Michigan. While a man goes out to work and “returns to his home with the sun, strong in heart and full of self-gratulation on the favourable change in his lot,” his wife has spent a “long, solitary, wordless day.” “Women are the grumblers in Michigan,” she writes, “and they have some apology. Many of them have made sacrifices for which they were not at all prepared, and which detract largely from their every day stores of comfort.”

If PBS ever runs a Frontier House II (and there’s scope for a sequel; incredibly, there were five thousand applicants for this first go-around), I’ll be sure to send the participants each a copy of Kirkland’s book. For women in 1839, as she writes, “the conviction of good accruing on a large scale does not prevent the wearing sense of minor deprivations.” Women were the grumblers on Frontier House, too, and not without cause. But perhaps they’re enjoying some kind of recompense for their five months of minor deprivations. Maybe they were sent home with a lifetime’s worth of Quilted Northern Bath Tissue.

Further Reading: See Caroline Kirkland, A New Home, Who’ll Follow? or, Glimpses of Western Life, ed. Sandra A. Zagarell (New Brunswick, 1999); Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (New York, 1998). See also the Frontier House Website. See also Jill Lepore, “Playing Dress Up,” Commonplace (Sept. 2000).

This article originally appeared in issue 3.1 (October, 2002).

Kristina Bross is an assistant professor of English and a member of the American studies program faculty at Purdue University. Her work has appeared in Early American Literature and books on American religious history, cultural studies, and postcolonialism. Her book manuscript, Dry Bones and Indian Sermons, examines the transatlantic production of the “Praying Indian” in seventeenth-century Puritan writings.